The PEN Ten: An Interview with Chantal V. Johnson

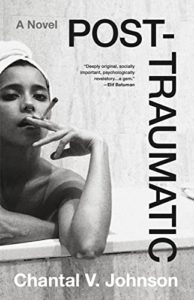

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Johnson speaks with Chantal V. Johnson, author of Post-Traumatic (Little, Brown & Company, 2022). Amazon, Bookshop

Photo Credit: Noah Barrow

1. What does your creative process look like? How did you maintain momentum and remain inspired while writing your debut novel Post-Traumatic?

My process is an utter mess! With Post-Traumatic, I had a centralized document that I kept adding to. I threw in any thought, description, or scene that even vaguely related to the subject matter. Later I began to combine like parts and build a novel. This is a chaotic way to write, and it seems to be what’s going to happen with my second book too.

In terms of momentum, I wrote Post-Traumatic while working full-time as a tenant lawyer, and it was partially this notion of writing against what I was doing for a living that kept me going. I was very driven to prove that I could write a novel despite not having an MFA, too, and that scrappy feeling was pretty motivating. During dark periods, I talked to friends who are writers and listened to interviews with authors I admired.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

In this novel, something I wanted to explore was a particularly post-traumatic consciousness, one characterized by hypervigilance, fear of harm, and a need to maintain bodily integrity. In some ways, it is a consciousness so overly concerned with truth that it has difficulty discerning the truth. For instance, Vivian constantly assesses risk as a survival strategy, but often she is wrong because she anxiously projects and overcorrects. I was also interested in writing about mental states that feel omniscient, such as shame. It is very hard to get out of shame once you’re in it because it seems correct and immune to challenge.

I tried to depict Vivian’s hyperactive mind while also creating some distance from it. Writing in close third-person helped with this. Also, certain other characters serve as counterpoints, presenting other possible truths and interpretations of reality. Vivian can take or leave those interpretations, but hopefully, it creates some breathing room for the reader. This all seemed like a decent structural way to get at something I’m interested in: other points of view exist, but simply knowing that other points of view exist does not necessarily make you any less trapped in or convinced of the truth of your own point of view.

“I feel like writing is one part reading, one part living, and one part actually writing. So first: read a lot and read widely. Figure out what you like and don’t like and why. Let your taste guide you as you write. Secondly, do stuff out in the world. Work, please. Get yourself into ridiculous situations, and take notes. Lastly, remember that writing is a test of psychological endurance. Get used to slowness, failure, doubt, and fallow periods. Learning how to move through this hard stuff is part of the job. The good thing is you don’t have to go through it alone: there’s a vast trove of “Writing Is Bad And Hard” literature.”

3. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I had strong reactions to both Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf when I was young. With Plath, I loved the severity of her language, her mannered style, and all of that obtuse diction. There is also a gendered anger in both her creative work and her journals. She is angry at her family, at her body, at the cosmic joke of being a woman. But all of this anger is expressed at some intellectual distance. Woolf’s attempt to map out the particular preoccupations of different minds in The Waves was hugely influential upon me and is still.

4. What was one of the most surprising things you learned—about the craft of writing, the questions you sought to explore in your novel, about the characters in or novel, yourself, etc.—while writing Post-traumatic?

Perfection isn’t possible, and that’s really annoying.

5. Some writers write with a specific reader in mind. This may be an individual, a group of people, a memory. Who, or what, did you envision as the reader when you were writing your novel?

I was always writing toward people who have experienced and/or witnessed extreme violence in childhood, and people who are estranged from their families. Also, women are forever on my mind, and always will be…especially women with big brains, and those who are deeply ambivalent about their gender.

6. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

6. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

I have tended to define myself reactively. So for instance, I sometimes feel and act like more of a writer around lawyers and more of a lawyer around writers. You can play that game with any of my many identities! It is an adolescent way of being, and it leads to constant angst, irritation, friction, and rebellion in social situations where identity feels rigid or circumscribed (in other words, many social situations in the United States right now). But these identity swerves are also valid attempts to fight my way out of the boxes that other people put me in.

It’s not just externally imposed though. People are actually limiting themselves, too! Playing into false binaries, reducing complex experiences to a single aspect of their identity. I find it all very bad and it goes into my work, obviously. Vivian has major defiant teen girl energy, and Post-Traumatic is in some ways disobedient.

7. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

The most daring thing I’ve done is to criticize the nuclear family and to depict a character choosing to walk away from hers. People who choose estrangement challenge established principles of life, as well as the very organization of life. They threaten the social order because the family is still the institution our culture reveres most.

8. What advice do you have for young writers?

I feel like writing is one part reading, one part living, and one part actually writing. So first: read a lot and read widely. Figure out what you like and don’t like and why. Let your taste guide you as you write. Secondly, do stuff out in the world. Work, please. Get yourself into ridiculous situations, and take notes. Lastly, remember that writing is a test of psychological endurance. Get used to slowness, failure, doubt, and fallow periods. Learning how to move through this hard stuff is part of the job. The good thing is you don’t have to go through it alone: there’s a vast trove of “Writing Is Bad And Hard” literature.

“I tend to be drawn to art that contains multiple tonalities, and that is a goal in my own work. Since Post-Traumatic deals with challenging material, I felt strongly that it also needed to have aspects of brightness and levity, which I achieved in part through ecstatic musical experiences and comedy.”

9. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Many of my favorite writers would probably be really awkward to talk to, so I won’t choose them; I believe in the art of conversation! I’ll say Elena Ferrante because I suspect that Ferrante can really talk. I’d also get to know their true identity and ask them why exactly they concealed it, as a bonus. Gossip gives me life.

10. The novel’s protagonist, Vivian, is an attorney at a psychiatric hospital who grapples with her own set of struggles—from dating to childhood trauma, an eating disorder to the turbulence of friendship. Yet, despite these weighty topics, the novel is deeply funny. How did you approach balancing humor with pathos when shaping, writing, and revealing Vivian’s distinct character, and addressing the novel’s broader themes?

I tend to be drawn to art that contains multiple tonalities, and that is a goal in my own work. Since Post-Traumatic deals with challenging material, I felt strongly that it also needed to have aspects of brightness and levity, which I achieved in part through ecstatic musical experiences and comedy.

Humor also felt important on the level of character. Characters like Vivian, Jane, and Cristina all use humor to cope with the difficulties of life, a strategy that I find so endearing, deeply alive, and generous. Someone with a comedic orientation is just constantly saying to her friends: look at this gift I made for you out of the bad things that happened to me!

I also like to write things I haven’t seen before, and through Vivian and Jane’s friendship, I was able to depict a powerful but unspoken aspect of post-traumatic life: the gallows humor of survivors. Survivor humor feels like domination to me. Abusers don’t like to be laughed at, you know.

Chantal V. Johnson is a tenant lawyer and writer. A graduate of Stanford Law School and a 2018 Center for Fiction Emerging Writers Fellow, she lives in New York.