The PEN Ten: An Interview with Azar Nafisi

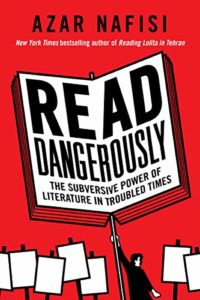

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Azar Nafisi, author of Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times (HarperCollins). Amazon, Bookshop

1. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Writing does not directly affect a resistance movement, but it helps shape the democratic mindset needed to create and sustain such a movement. Great resistance movements, like the Civil Rights Movement, have one essential thing in common with great writing: they both oppose lies fabricated by autocratic mindsets. Writers are witnesses to the Truth and great writing is an act of revealing the Truth. And Truth is always dangerous, for once it has been revealed we cannot remain silent, lest we become complicit. Fiction, through its democratic structure, resists the rule of totalitarianism, which imposes its own voice upon all other voices. Great fiction gives voice to diverse characters coming from different backgrounds and beliefs. It even gives voice to those we think of as villains.

2. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

Beginning when I was about three years old, each night my father would tell me a story. One night we would visit our epic poet Ferdowsi, who lived more than a thousand years ago, to learn about ancient Persia and its mythologies. The next night we might travel to France with the Little Prince. Or to Britain with Alice, to Denmark with the little match girl, to America with Charlotte and her web, to Italy with Pinocchio, or to Turkey with Mullah Nassredin. So, from a very young age, I felt that I had the power to stay in my little room in Tehran and yet bring the whole world into it through storytelling. I still return to that room in my imagination to gain strength from stories.

“Writers are witnesses to the Truth and great writing is an act of revealing the Truth. And Truth is always dangerous, for once it has been revealed we cannot remain silent, lest we become complicit.”

3. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Can you describe some instances when your right to free expression has been challenged?

The biggest threat to free expression today is the totalitarian mindset, which entrenches ideological polarization and prevents the free flow of ideas. I have experienced this mindset while living in the Islamic Republic of Iran. As a writer, I watched as my book was not allowed to receive a second printing. For a while it was sold in the black market, but later it disappeared from there as well. In my teaching career, I was constantly reprimanded for the books I taught, my open relationship with my students, and the subversive conversations that took place in my classes. And as a woman, I was forced to censor my body, covering it except for the oval of my face.

I had to find creative ways of resisting this censorship. I taught books that were about freedom but seemed apolitical, like Pride and Prejudice. Austen was, I thought, an ideal rebuke for a regime that on its coming to power changed the age of marriage for females from eighteen to nine. I never wore my veil properly and was constantly reprimanded for it, but just showing a bit of hair was for me, as it was for millions of other Iranian women, a message to the regime that they had not won their battle to control us. But my own experiences are nothing compared to what some poets, writers, artists and journalists have suffered for their defense of free speech. As PEN is well knows, so many have been not just censored, but jailed, tortured, and even killed for their defense of free expression.

4. Read Dangerously is a guide to the power of literature and its capacity to galvanize readers in times of political strife. In writing this, you drew from your experiences as a reader both in your home country of Iran and as an immigrant in the United States. Can you tell me about what first inspired you to write this book?

Here, I must thank two dubious sources of gratitude: Donald Trump and the Islamic Republic of Iran. For quite a while I had been feeling frustrated with what was happening in the two places I have called home. In Iran violence against the Iranian people continued and in America the 2016 election brought to the surface hostilities that had been brewing for years. As I always do when I feel frustrated, I took to writing. Writing helps me clarify ideas and thoughts—rather than remaining in a permanent state of exasperation. How, I wondered, do we deal in a democratic manner with the growing totalitarian trends?

I did not want to write literary essays. I needed a more intimate form, a form that while personal would also provide enough distance for discourse. So I began to write letters. At first I wrote to all sorts of people, including Donald Trump. Then I wrote to writers whose books I was thinking about, but since I did not know them personally, the letters felt stilted and artificial. One day I was talking to a friend, who suggested: Why don’t you write to a third person? And almost immediately my father came to my mind.

He and I had a long history of letter writing. The first letter he wrote addressed to me was when I was four years old and could not yet read. In it, he wrote about his feelings, his life, his dreams for the future and the impact I had already had on his life. The first time I wrote to him was when I was six and had just learnt to read and write. I wrote him a few lines on scraps of paper while he was studying in America, and he wrote me long letters in return. We continued this habit for the rest of his life, and my conversations and correspondence with my father became the main source of inspiration for this book. Since my childhood he had communicated to me through stories. Now it was my turn to tell him my stories.

5. There are plenty of people living in the U.S. who believe that free expression issues only affect non-western countries–people living in faraway places with state-controlled media. To them, the very existence of the First Amendment is surely testament to this. However, the U.S. has a long history of censorship that is only gaining traction today, with the newest onslaught of book bans and educational gag orders. Why do you think it is so difficult for these folks to see that even in this country, the ability to read freely is not a guarantee?

This attitude is quite condescending. It assumes that freedom is a western entity and non-western countries do not want it. The arrogance of such claims is rooted in an ignorance of the world and of the west’s history. Freedom is not God-given. So many people have given their lives in order to have freedom and freedom needs to be nurtured and nourished otherwise it will wither and die. How could we say free expression cannot be in danger in the west, when the history of the west includes slavery and fascism? If it has happened before it can happen again.

6. How has your identity shaped your writing?

6. How has your identity shaped your writing?

As an immigrant I have a dual identity shaped by both the country of my birth and the country that I now call home. I like this double identity because both the Iranian and American side of me can see itself through the alternative eyes of the other. This metaphorical way of looking at the world is good for my writing. It even affects the language I use; it seems as if the lights and shades of one language penetrate and shine through the other.

7. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

I have always been interested in the interaction between fiction and reality—and how each affects our perception of the other. Literary criticism for me is a way of having a conversation with the text I am reading. But in the Islamic Republic both fiction and reality were constantly mutilated and censored, so I had to write in a more academic style. Apart from rare cases, I would avoid bringing my own personal experiences into what I wrote. But since immigrating to the United States I have been mixing personal narrative with discussion of literary texts, and this has completely changed my style.

8. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

Opposite my desk there is what looks like a painting but is in fact a photograph of old books in the process of disintegration. I have named it Falling Time. It belongs to a group of photographs gathered in a book called Last Folio, A Photographic Memory by the Slovakian-Canadian photographer, Yuri Dojc and his colleague and producer Katya Krausova.

One day in October 1942, the Jews of a small town in Slovakia were rounded up and taken to concentration camps. Nothing remained of them, except among the ruins of buildings, in schools and synagogues, their books. These books survived, just where they had left them, as if they had been waiting for Yuri and Katya to travel to Slovakia to photograph them. Yuri photographed the books as they were in the process of disintegration. When I first saw the photographs, I wrote how I felt about them: “Books in these photographs are not mere objects; they are possessed by spirits exorcized through Yuri Dojc’s magical eye: as they disintegrate into dust, the camera illuminates how that moment of disintegration is also a moment of immense energy and movement, one last and glorious statement of defiance, resisting both death and oblivion.” I still feel the same way about them.

These books rescue their owners from decades of oblivion, reminding us of the power of art that safeguards memory against the fickleness of life and absoluteness of death.

One last thing: On one ruined page Yuri found a word in Hebrew. Hanishar. It means “All that remains.”

“Do not allow the present moment to control your writing; rather, write to control the seemingly uncontrollable reality.”

9. What advice would you give to a writer who is trying to publish their book–not just in general, but especially in this current climate?

I advise them to listen to the beat of their heart, and write to that beat. These times are overwhelming, but do not be overwhelmed. Do not allow the present moment to control your writing; rather, write to control the seemingly uncontrollable reality.

10. What brings you hope in times like this?

We live in times of crisis and transition. Things could turn either toward totalitarianism or toward democracy. It all depends on us. My hope is that there are enough people who view hope the way Vaclav Havel described it:

“Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense regardless of how it turns out.”

Azar Nafisi is the author of the multi-award-winning New York Times bestseller Reading Lolita in Tehran, as well as Things I’ve Been Silent About, and The Republic of Imagination. Formerly a Fellow at Johns Hopkins University’s Foreign Policy Institute, she has taught at Oxford and several universities in Tehran, and she is currently Centennial Fellow at Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service. Nafisi has written for publications that include The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Republic, and The Wall Street Journal. She lives in Washington, D.C.