Reading Between the Lines: Race, Equity, and Book Publishing

Introduction

In 2020, the publishing industry entered a moment of moral urgency about the persistent lack of racial and ethnic diversity among employees and authors. The industry is disproportionately white, and the canon of published books from trade publishers is overwhelmingly so. According to one analysis, 95 percent of American fiction books published between 1950 and 2018 were written by white people.1Richard Jean So, Gus Wezerek, “Just How White Is the Book Industry,” The New York Times, December 11, 2020, nytimes.com/interactive/2020/12/11/opinion/culture/diversity-publishing-industry.html. While that analysis looks at a broad sweep of time, more recent figures indicate that both the publishing industry, and the books it puts out, remain disproportionately white. The lack of diversity in the ranks of publishing professionals and in the works brought to market are linked: In a cultural industry like publishing, where subjective interpretations of what constitutes good or marketable literature are a major determinant of what gets published, the whiteness of the industry’s staff has accompanied a largely white cadre of published authors.

Not only is the United States a demographically diverse nation—as of the last census, an estimated 42 percent of the country are people of color2Mabinty Quarshie, Donovan Slack. “Census: US sees unprecedented multiracial growth, decline in the white population for first time in history,” USA Today, August 12, 2021, usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2021/08/12/how-2020-census-change-how-we-look-america-what-expect/5493043001/—it also boasts a demographically diverse readership. The National Endowment for the Arts estimates that approximately a quarter of America’s regular adult readers are people of color.3James Murdoch, Mark Bauerlein, Marie Halverson, Natalie Morrissey, Esther Galadima, “How Do We Read? Let’s Count the Ways,” National Endowment for the Arts, March 2020, arts.gov/sites/default/files/How%20Do%20We%20Read%20report%202020.pdf.arts.gov/sites/default/files/How%20Do%20We%20Read%20report%202020.pdf For decades, voices within and outside the publishing industry have called on publishing houses and bookstores to more fully reflect this demographic diversity.4For the purposes of this report, by ‘diversity,’ PEN America refers to racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity. This report’s focus on racial and ethnic diversity should not be construed to imply any commentary regarding the importance of other indices of diversity—such as diversity of sexual orientation or gender identity, or diversity regarding differently-abled people. In response to calls for publishers to heed and support employees and authors of color, the publishing industry has gone through waves of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts. But over time, many of these gains have turned out to be temporary or insufficient. Industry experts and longtime editors have occasionally aired their frustrations with these cyclical, transient attempts. As fifty-five year publishing veteran Marie Dutton Brown put it in a 2020 interview: “Black life and Black culture are rediscovered every 10 to 15 years. Publishing reflects that.”5Richard Jean So, Gus Wezerek, “Just How White is the Book Industry,” The New York Times, December 11, 2020, nytimes.com/interactive/2020/12/11/opinion/culture/diversity-publishing-industry.html

Over the past several years, major publishers have ramped up their efforts to diversify the racial and cultural composition of their workforces and author lists. They do so while facing—and in part spurred by—a groundswell of activism, including from authors and editors of color, calling on the industry to change. At the same time, activists have seen the rise of social media–enabled advocacy, from the #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement (a hashtag-turned-organization that advocates for more diverse children’s books) to the #PublishingPaidMe movement (a 2020 campaign that called on authors to disclose their advances to expose discrepancies in payment between white authors and those of color).

Beginning in the summer of 2020, the society-wide confrontation of racial justice issues in the United States prompted a renewed reckoning. As the killing of George Floyd and the resurgence of Black Lives Matter instigated a sea change in the way Americans have approached race and racism, book publishers were among the corporate institutions that have pledged to be part of this change. A New York Times article in June 2022 noted that in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, “the number of nonwhite employees in the publishing industry surged,” editors “scrambled to buy manuscripts from nonwhite authors,” and publishing houses “doubled down on their efforts to recruit and support their nonwhite employees and to examine their procedures through diversity, equity, and inclusion councils.”6Marcela Valdes, “Inside the Push to Diversify the Book Business,” The New York Times, June 22, 2022, nytimes.com/2022/06/22/magazine/inside-the-push-to-diversify-the-book-business.html.

Recent activism and reform efforts have pressed for a broad scope of actions to overcome systemic racial inequities in the publishing industry and achieve sustained, holistic, and structural change. PEN America’s research and interviews suggest that measuring and addressing racial representation in employee hiring, author lists, and published content are key metrics for evaluating long-term diversification.

But diversity in the books sector isn’t just a question of who is on editorial staffs and which authors receive book contracts. Our research and interviews revealed a host of historically underexplored financial and institutional factors that feed into underrepresentation across the industry, and compound the marginalization of publishing professionals, authors, and booksellers of color. These factors include policies and strategies for entry-level pay, author advances, employee retention, professional mobility, mentorship, book sales, audience development, and marketing—all of which shape a book’s chance of publication and commercial success as well as an author, bookseller, or publishing professional’s capacity to remain and flourish in the industry.

Today we find ourselves in the midst of a promised shift, with publishing houses launching signature initiatives, hiring new personnel, and making high-level strategic decisions designed to prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion. The Big Five U.S. publishers—Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House (PRH), and Simon & Schuster—collectively control over 80 percent of the so-called trade publishing market, encompassing books sold to a general audience.7“Hagens Berman: Booksellers Sue Amazon and Big Five Publishers for Alleged Monopoly Price-Fixing the U.S. Print Book Market,” Business Wire, March 25 2021, businesswire.com/news/home/20210325005940/en/Hagens-Berman-Booksellers-Sue-Amazon-and-Big-Five-Publishers-for-Alleged-Monopoly-Price-Fixing-the-U.S.-Print-Book-Market; As of publication, there is an ongoing legal case between PRH and the Department of Justice to permit PRH to buy competitor Simon & Schuster, a move that would shrink the Big Five to the Big Four. Their actions—including through their various imprints—will be determinative in shaping the diversity, equity, and inclusion of the trade book sector at large, but there are also hundreds of midsize and small independent publishers that play a role in determining the industry’s direction.

PEN America is convinced that the industry has embarked on current reforms with a genuine desire to make change. But systemic change requires more than goodwill. It necessitates specific, far-reaching, and sustained policy revisions and company-wide commitments that outlast any single political moment and persist despite inevitable hurdles and setbacks.

If publishers are the curators of our country’s stories, they have an obligation to ensure that these stories reflect the breadth of our society. Current diversity statistics, alongside the testimony of many publishing and writing professionals of color, point to persistent obstacles and shortcomings in fulfilling this responsibility.

PEN America undertook this report to better understand why the debate over the lack of diversity in publishing has seemed to stagnate, or to progress only in fits and starts. Our hope is to shed light on the dynamics that both enable and inhibit the broadest range of voices in American literature. In researching this issue, PEN America focused on racial and ethnic diversity—acute and urgent, if not the sole, areas of under-representation. Our research and analysis incorporate interviews, conversations with major publishers, and open-source data and draw on PEN America’s deep contacts with authors and editors and throughout the field of adult trade publishing.

This report is primarily informed by more than 60 interviews with authors and publishing professionals, including agents, editors, salespeople, marketing and publicity specialists, and publishers. The interviewees range from longtime veterans to recent hires and represent independent presses such as Graywolf and Akashic as well as the Big Five. While many agreed to speak on the record, a significant number chose to speak anonymously or off the record to avoid impairing their career prospects or personal relationships. PEN America has made every effort to select sources whose reliability could be established.

|

|

Report ContentsThis report has five sections.

|

|

Section I: The Color of Publishing

How disproportionately white is America’s corpus of stories? Although there is no regularized, industry-wide system that tracks the racial identities of published authors, there are several sets of numbers that help to paint a picture.

The most comprehensive evaluation of racial diversity among trade authors came in 2020, when McGill University professor Richard Jean So and New York Times graphics editor Gus Wezerek compiled a data set of approximately 8,000 fiction books by 4,100 authors published by major American publishing houses between 1950 and 2018. The research team identified the race or ethnicity of almost 3,500 of these authors. They concluded: “We guessed that most of the authors would be white, but we were shocked by the extent of the inequality once we analyzed the data. Of the 7,124 books for which we identified the author’s race, 95 percent were written by white people.”8Richard Jean So, Gus Wezerek, “Just How White is the Book Industry,” The New York Times, December 11, 2020, nytimes.com/interactive/2020/12/11/opinion/culture/diversity-publishing-industry.html While the results of this research emphasize trends across decades and may hide recent historical gains, they paint a sobering picture of publishing as an institutionally white field.

Richard Jean So analyzed this data both in his 2020 book Redlining Culture and in a piece published in The New York Times in December of that year. Speaking to PEN America about the significance of this research, So said: “I wouldn’t say I was surprised by these results, but it was a learning process. We focus so much on the success of a few individual writers that we don’t realize that’s like all there is, that there’s not a much larger community” of books from writers of color. “But when you really get into the data of it—actually, no, there’s not.”9PEN America interviews with Richard Jean So, April 2021 and October 2021.

Of the Big Five publishing houses, only two—Penguin Random House and Hachette—have publicly disclosed author diversity statistics.

Penguin Random House released its first-ever public, multiyear report on the subject in December 2021.10An audit of the diversity of Hachette Book Group’s publishing programs was completed and distributed to employees in June 2020, indicating that 22% of 2019 acquisitions by authors and illustrators new to the HBG lists were persons of color. No other numbers are publicly available. hachettebookgroup.com/corporate-social-responsibility/an-update-on-hbgs-diversity-and-inclusion-efforts/ Their stats revealed that white U.S. contributors (authors, illustrators, and translators) accounted for 74.9 percent of the books released by the publishing giant between 2019 and 2021—a number significantly higher than the percentage of white people in the general population but one that tracks closely with the percentage of white employees in PRH’s U.S. workforce (74.2 percent).11“PRH U.S Publishing Programs Audit Findings,” PRH, accessed June 16, 2022, penguinrandomhouse.com/penguin-random-house-u-s-publishing-programs-audit-findings/ Contributors of color constituted 23.5 percent, including 6.8 percent Asian, 6 percent Black, 5 percent Hispanic or Latinx, 2.1 percent Middle Eastern or North African, and 3.3 percent two or more races, with less than 1 percent each for American Indian and Pacific Islander.12 PRH U.S Publishing Programs Audit Findings,” PRH, accessed June 16, 2022, penguinrandomhouse.com/penguin-random-house-u-s-publishing-programs-audit-findings/

Hachette has disclosed its broad statistics for recent acquisitions of authors of color in comparison with white authors since 2020. In March 2022, Hachette released its third annual report on diversity equity and inclusion–including author diversity statistics. The publishing house disclosed that 34 percent of contracts with new contributors in 2021 were with self-identified BIPOC authors and illustrators, compared to 29 percent in 2020, and 22 percent in 2019.13Hachette Book Group, An update on HBG’s diversity, equity and inclusion efforts (March 2022), https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/an-update-on-hbgs-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-efforts-march-2022

Elizabeth Méndez Berry is a vice president and executive editor of the PRH imprint One World as well as the founder of Critical Minded, an initiative to support cultural critics of color. She told PEN America that while the publishing industry doesn’t control what the consumer buys, “we do play a big role in defining what they can buy. And when you put that in historical context—the millions of stories in New York and hundreds of millions of stories in the country—[when] we primarily publish books by white authors, the number of stories that we’re avoiding or suppressing is significant. It’s exciting that we’re starting to see a shift in acquisitions, but you have to remember that this shift is happening against a backdrop of decades upon decades that told a narrow story of what this country has been and could be. We have a lot to make up for.”14PEN America interviews with Elizabeth Méndez Berry, May and October 2021

A Changing Industry: Publisher Action Meets Literary Activism

In recent years, publishers have pledged to renew their commitment to diversity. In 2017, Penguin Random House, which accounts for an estimated 25 percent of U.S. trade book market15Benjamin Mullen and Jeffrey A. Trachtenberg, “Penguin Random House Parent to Buy Simon & Schuster From ViacomCBS,” Wall Street Journal, Nov. 25, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/penguin-random-house-parent-near-deal-to-buy-simon-schuster-from-viacomcbs-11606268232 and, as of this writing, was trying to fend off an antitrust challenge to its bid to acquire rival Simon & Schuster, began an employee-led diversity, equity, and inclusion initiative. In 2019, PRH contracted with an outside consultant, Paradigm, to conduct an in-depth company culture survey, followed by focus groups with company employees. U.S. CEO Madeline McIntosh found the results eye-opening. “On every measure,” she told PEN, “there was just such a significant gap in empowerment, to put it simply, where everybody—everybody—rated below straight, white men. In the focus groups, it became clear that that was affecting business decisions as simple as how a cover is designed.” Many employees reported that in the course of doing their jobs, they felt they didn’t have the opportunity to voice their opinions, or that if they did speak up, their opinions weren’t taken seriously.16PEN America meeting with Penguin Random House, March 7, 2022

McIntosh said: “I was already very clear that publishing is a very monocultural industry, and has historically been a very monocultural industry, very much dominated by a single race—and that there is particularly a history of a fairly privileged class element within publishing that was paired with historically low compensation rates in the industry. But … it was really revelatory to see the degree in which, even in a company culture that considered itself to be progressive and forward-thinking and inclusive, that in reality that experience was very different depending on your identity.”17PEN America meeting with Penguin Random House, March 7, 2022

In the past decade, new forms of literary activism have arisen to push for greater diversity in publishing. In April 2014, young-adult-fiction authors Ellen Oh, Malinda Lo, and Aisha Saeed, reacting online to an all-white and all-male panel of children book authors at that year’s BookCon gathering, began campaigning for greater attention to diversity in the children and young-adult sectors, adopting the Twitter hashtag #WeNeedDiverseBooks. Soon after, a group of writers and publishing insiders founded We Need Diverse Books as an organization aiming “to produce and promote literature that reflects and honors the lives of all young people.”18“About Us,” We Need Diverse Books, accessed June 16, 2022, diversebooks.org/about-wndb/; “FAQ” “Official Tumblr of We Need Diverse Books, accessed August 1, 2022, weneeddiversebooks.tumblr.com/FAQ. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center has found that We Need Diverse Books has had a major impact, prompting a meaningful rise in authors of color.19University of Wisconsin Madison, School of Education, Cooperative Children’s Book Center -Diversity Statistics FAQs- ccbc.education.wisc.edu/literature-resources/ccbc-diversity-statistics/diversity-statistics-faqs/ In 2016, a group of Hispanic publishing professionals created Latinx in Publishing to connect authors and publishers with readers and to boost the Hispanic presence in the industry.20Carlos Rodríguez-Martorell, “Taking a Look at Latinx in Publishing,” Publishers Weekly, June 29, 2018, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/77406-taking-a-look-at-latinx-in-publishing.html.

These efforts accelerated in mid-2020 as a society-wide reckoning with racial justice reverberating throughout the publishing industry. In June of that year, author L.L. McKinney started the Twitter hashtag #PublishingPaidMe, calling on writers to reveal the advances they received for selling their books to publishers.21Authors receive an advance, usually paid in three installments, upon selling a book. They only begin earning royalties on sales after revenue from sales exceeds the amount of the advance. That same month, employees at the Macmillan imprint Farrar, Straus, and Giroux organized a “Day of Solidarity” for publishing professionals to “speak out against racist murder, white supremacy, and racial capitalism.”22John Maher, “Workers Across Book Business Take Collective Action Against Racism,” Publisher’s Weekly, June 8, 2020, https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/83536-workers-across-industry-take-collective-action-against-racism.html It asked publishing professionals to work on projects featuring Black authors, donate a day’s pay, or otherwise support Black writers. At least 1,300 workers across the industry ended up participating.23Concepción de León, Elizabeth A. Harris, “#PublishingPaidme and a Day of Action Reveal an Industry Reckoning,” The New York Times, June 8, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/08/books/publishingpaidme-publishing-day-of-action.html

The #PublishingPaidMe revelations were both predictable and alarming. Author Jesmyn Ward, who is Black, disclosed that even after Salvage the Bones, her second novel (for which she received an advance of about $20,000), received a National Book Award, she had to fight furiously, and switch publishers, to receive $100,000—“barely equal to some of my writer friends’ debut novel advances”—for her next novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing. That book also went on to win a National Book Award. Science fiction writer N.K. Jemisin, who is also Black, reported that she received only $25,000 advances for each book of her Broken Earth trilogy—all of which went on to receive the Hugo Award, making Jemisin the first author in the award’s 65-year history to win three times in a row.24Concepción de León, Elizabeth A. Harris, “#PublishingPaidme and a Day of Action Reveal an Industry Reckoning,” The New York Times, June 8, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/08/books/publishingpaidme-publishing-day-of-action.html; Aja Romano, “The Hugo Awards just made history, and defied alt-right extremists in the process,” Vox, August 21, 2018, vox.com/2018/8/21/17763260/n-k-jemisin-hugo-awards-broken-earth-sad-puppies

As part of the #PublishingPaidMe discussion, a Google spreadsheet of advances began to circulate with nearly 1,200 self-reported entries. Of these, 122 authors revealed that they received an advance of at least $100,000. Of those 122 authors, 78 identified themselves as white, compared with just seven who identified as Black and two as Latino or Latina.25The #PublishingPaidMe spreadsheet can be found at docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Xsx6rKJtafa8f_prlYYD3zRxaXYVDaPXbasvt_iA2vA/edit#gid=1798364047. As of August 2022, the number of entries is slightly more than 2,800. The remaining authors identified as Asian, Middle Eastern, Multiracial, Native American/First Nations, Nonwhite, or did not share. As of August, 346 authors self-reported receiving an advance of at least $100,000. Of those authors, 232 identified as white, twenty-six as Black, and four as Latin American. While the spreadsheet was not comprehensive, many commentators nonetheless pointed to the results as another indication that publishing favors white authors and audiences.

The #PublishingPaidMe discussion brought the long-secretive subject of advances at least partly out in the open. “The #PublishingPaidMe hashtag really showed us the inequality that exists, where a Black writer with even a big following might be getting three, five, ten times less than a white author that isn’t equal at all in terms of audience,” Rebekah Borucki, founder and president of Row House Publishing,26Rebekah Borucki. (n.d.) Experience, accessed August 1, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/in/rebekahborucki/ told a writer for Forbes, noting that the online debate sparked widespread frustration among publishing professionals and writers of color.27Michelle King, “How To Disrupt The Publishing Industry And Do Better,” Forbes, November 24, 2021, forbes.com/sites/michelleking/2021/11/24/how-to-disrupt-the-publishing-industry-and-do-better/?sh=6a8fa52abc63 Writer Leah Johnson, author of the acclaimed young-adult novel You Should See Me in a Crown, posted on Twitter that #PublishingPaidMe was “one of the most important things that could have ever happened in publishing,” adding: “We’re still witnessing a shift in culture that was kickstarted by a newfound transparency around wage disparity (and the expectation of overwork for minimal compensation) . . . It’s difficult to understand how underwater you are when you have no concept of where the surface is.”28 Leah Johnson, “I think one of the most important things that could have ever happened in publishing was #PublishingPaidMe,” Twitter, April 18, 2022, twitter.com/byleahjohnson/status/1516125126668038144

As a direct result of #PublishingPaidMe and the discrepancies it revealed, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, a recipient of the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award for his story collection Friday Black, was able to renegotiate his advance for his next book. But he told PEN America that as he scrolled through his feed at the time of the initiative, he couldn’t help noting the absence of “so, so many of these white male authors that I see all the time on Twitter . . . And I keep that in my head.” While Adjei-Brenyah expresses gratitude toward “the white writers who stepped up and made more clear and transparent that disparity,” he said that for the most part, on the subject of equity in book advances, “it’s really always the people of color talking about this, people of color on the diversity counts, people of color trying to fix things—and where are the white people trying to help us?”29PEN America interviews with Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, April and September 2021

Publisher Commitments

That same month, in response to the broad national call for reckoning and to targeted activism among their authors, employees, and audiences, major publishers made a series of public commitments, in some cases pledging to implement major initiatives to address racial inequities in their institutions.30Jim Milliot, “Publishers Promise More Action to Diversify Industry,” Publishers Weekly, June 9, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/83542-publishers-promise-more-action-to-diversify-industry.html PRH vowed to disclose statistics on employee demographics, publish more books by people of color, mandate antiracist training among its staff, and hold a company-wide reading assignment of Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist. Michael Pietsch, the CEO of Hachette Book Group, announced that it would provide staff demographic information and create diversity targets for its staff and authors.31 Concepción de León, Elizabeth A. Harris, “#PublishingPaidme and a Day of Action Reveal an Industry Reckoning,” The New York Times, June 8, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/08/books/publishingpaidme-publishing-day-of-action.html

Each of the Big Five publicly voiced support for Black Lives Matter and articulated new company principles about racial equity and justice. PRH promised to “stand against racism and violence toward the Black community” and to “commit to listening—to our readers, to our authors, and to our teams—as we work toward becoming part of the change.”32 “Black Lives Matter,” PRH, accessed June 16, 2022 prhspeakers.com/black-lives-matter HarperCollins Publishers pledged to “stand with all of our colleagues, authors, readers, and partners who experience racism and oppression.”33Bea Koch, Leah Koch, “Diversity in Romance Books Still Lags,” Publishers Weekly, March 2, 2021, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/85707-diversity-in-romance-books-still-lags.html#:~:text=On%20June%201%2C%202020%2C%20seven,who%20experience%20racism%20and%20oppression. Hachette declared that it would “support Black writers, readers and people of color by sharing their stories and experiences in many of the books we publish.”34Richard Jean So, Gus Wezerek, “Just How White is the Book Industry,” The New York Times, December 11, 2020, nytimes.com/interactive/2020/12/11/opinion/culture/diversity-publishing-industry.html Macmillan released a statement against racism, canceled internal meetings for a day in June to allow for discussions, added Juneteenth as a company-wide holiday, and offered a double matching program for donations to racial justice causes that led to over $400,000 being donated to groups including the Black Lives Matter Global Network.35PEN America communication with Macmillan, March 2022; Pan Macmillan statement on Black Lives Matter and Diversity and Inclusion, June 8, 2020, https://www.panmacmillan.com/blogs/general/diversity-and-inclusion; Macmillan Publishers, Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, https://us.macmillan.com/diversity/ Simon & Schuster announced that it was “committed to working with our employees, authors and the publishing community to make our company and our industry a safe and inclusive environment for all, and a publisher of works that represent the breadth and depth of our diverse population.”36Jim Milliot, “Publishers Promise More Action to Diversify Industry,” Publishers Weekly, June 9, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/83542-publishers-promise-more-action-to-diversify-industry.html This public statement followed a June 1 internal letter from CEO Jonathan Karp to employees—a copy of which the publisher provided to PEN America—that said, “We stand with our colleagues, authors, and the many citizens both within the world of publishing and the greater population who have mobilized in the cause of social justice and in proclaiming that yes, Black Lives Matter.”37Letter provided to PEN America on March 3, 2022.

PEN America spoke with representatives of each of the major five publishing houses to better understand how they have worked to actualize these pledges. Some publishers stressed that much of the work they view as most influential in promoting diversity occurred prior to 2020; still, each of the Big Five acknowledged the importance of June 2020 as a catalyst for the industry.

Based on these conversations as well as research and interviews, PEN America developed the following metrics to assess whether, and to what extent, publisher diversity statements have translated to structural change.38See interviews and research in report as well as resources and leaders for assessing DEI initiatives in media and beyond, including Academy to Innovate HR, Cindi Howson at ThoughtSpot, Holly Falk-Krzenski, and Letrell Crittenden. (As these metrics intend to evaluate structural change, we have omitted instances of individual and ad hoc editorial and commercial decision-making, which, while important, are more difficult to evaluate and may not reflect long-term, company-wide policy. These metrics are not intended as a comprehensive description of all publisher commitments and efforts, but as an illustration of Big Five activity in several important areas.)

| Simon & Schuster | Penguin Random House | Macmillan | Hachette Book Group | HarperCollins | |

| Does the publisher collect employee DEI statistics? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Are the DEI statistics publicly available? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Does the publisher have explicit DEI hiring benchmarks and targets? | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Does the publisher have a professional DEI Officer and/or Team? | Yes39Amanda Armstrong-Frank was appointed Director of Workplace Culture and Diversity Initiatives in September 2020. | Yes40Kimberly Ayers Shariff was appointed Executive Vice President, Director of Strategy for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, in April 2021 and leads a team of 4. PRH staffing also includes additional divisional DEI strategic roles. | Yes41LaToya Rose was appointed Vice President of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion in August 2020, and promoted to SVP, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in April 2022. | Yes42Carrie Bloxson was appointed VP Diversity and Inclusion in December 2020. | Yes43Gisselda Nuñez was appointed VP Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in September 2020. Harper Collins also has a dedicated DEI team. |

| Is there a DEI Officer that reports directly to the CEO or COO? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes*44Gisselda Nuñez was appointed VP Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in September 2020. Harper Collins also has a dedicated DEI team. |

| Does the publisher require DEI training for all staff? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Does the publisher track and/or collect author/contributor DEI statistics? | Yes | Yes | No*45Macmillan is planning to launch a voluntary author demographic survey by 2023. | Yes | Yes |

| Are they publicly available? | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Does the publisher track and assess equity in author advances? | No | No | No | No | No |

| Does the publisher have an Officer or Team specifically dedicated to multicultural marketing? |

Yes46Sienna Farris was appointed Simon and Schuster’s inaugural Vice President and Director of Multicultural Marketing in October 2020. | Yes47In 2020, a dedicated team leading multicultural marketing strategy was formed: Anthony Key was appointed Director of Multicultural Marketing in September 2020. Susette Brooks was appointed Director of Strategy, Diversity, Equity & Inclusion, Penguin Publishing Group, in February 2021. Carolina Meurkens, Manager, Multicultural Marketing, Penguin Publishing Group, was appointed in May 2022. |

No | Yes*48Former Director of Multicultural Publicity, Linda Duggins, started in 2006 and left in March 2021. The marketing strategy team regularly meets with the Chief Diversity Officer. | Yes49Hired dedicated manager role within Sales group for amplifying Black authors and building relationships with BIPOC bookstores. |

Since 2020, several diversity initiatives have been adopted by all of the Big Five publishing houses, becoming new baseline standards, particularly in the hiring and recruitment processes. These include the creation of new retention, hiring, and funding initiatives; the appointment of formal DEI officers, many of whom serve on and/or report to senior-level management; and a turn toward data to track and analyze employee diversity.

Other areas reflect a lack of uniformity in implementation. These include multicultural marketing officers and strategy; staff-wide diversity and inclusion training (acknowledging that the quality and value of such training can vary widely, making this metric difficult to assess); and the collection and publication of diversity statistics for a publishing house’s authors and other contributors. As of August 2022, none of the Big Five had publicly disclosed information on author advances.

PEN America’s research underscores that diversity in the book market is not simply a matter of getting employees and authors of color through the door. Each publishing house is operated and structured somewhat differently, obviating exact comparisons among their strategies to achieve greater diversity, equity, and inclusion. Nonetheless, we hope that by disclosing the information we did obtain on affirmative efforts to address these issues, we can prompt further discussion and progress. Intentional marketing, workplace culture transformation, and large-scale diversification in publishing houses are crucial for ensuring that diverse stories and storytellers can thrive.

According to the Publishers Weekly 2020 report on workplace diversity, 75 percent of industry respondents said that their employer had increased their diversity and equity efforts in the past year by broadening recruitment efforts (for instance, by expanding outreach at historically Black colleges and universities), hiring DEI experts and holding training sessions, adding a retail manager to work with bookstore owners of color, auditing author demographics, boosting marketing support for titles by authors of color, and raising entry-level salaries. Roughly half of the respondents whose workplaces added a DEI initiative said they believed the initiative would result in real change at their workplace.50Jim Milliot, “Are Book Biz Diversity Efforts Starting to Kick In?,” Publishers Weekly, December 31, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/85222-are-book-biz-diversity-efforts-starting-to-kick-in.html

Overall, it is too early to evaluate how much long-term change this burst of post–George Floyd efforts will bring. Clearly publishing is investing in reform in unprecedented ways, impelled in large part by industry professionals, authors, and others proponents of change.

Halting Progress: Diversity in Fits and (False) Starts

Dating back to the 1960s, publishing companies have mounted initiatives and started imprints focused on authors of color, and industry publications have covered questions of diversity and inclusion within major houses.51Mel Watkins, “Hard Times For Black Writers,” The New York Times, February 22, 1981, nytimes.com/1981/02/22/books/hard-times-for-black-writers.html Experts and longtime insiders have warned that these past efforts have waxed and waned, receiving substantial fanfare, then dying down as public and media attention diminished. Many of PEN America’s interviewees referenced previous unfulfilled promises to transform, evincing leeriness about whether this time things will be any different. Despite this wariness, many interviewees voiced hope that current efforts would prove more serious and permanent.

“We are both at a demographic inflection point and an inflection point in terms of the future of our democracy,” said Tanya McKinnon, a literary agent for more than 20 years.52Diane Patrick, “Meet the Agent: Tanya McKinnon,” Publishers Weekly, July 24, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/people/article/83962-meet-the-agent-tanya-mckinnon.html McKinnon argued that to surmount cyclical patterns of progress and regression, publishers need “to feel a real normalization toward acquiring and publishing books by people of color well. That is a first step, so that publishing voices of color doesn’t feel like an anomaly, that it doesn’t feel like it’s something that’s a response to the moment but that it’s an ongoing commitment—to publish consistently, and well, the work of people who reflect the face of America.”53PEN America interview with Tanya Mckinnon, May 2021.

Some of those interviewed by PEN America express cautious optimism that a combination of attitudinal, societal, and commercial changes have combined to make progress irreversible. Ibrahim Ahmad, former editorial director of the Akashic Books, said that his decision to move from an indie publisher to Viking Books, a PRH imprint, in 2021,54“Ibrahim Ahmad, Executive Director,” Penguin Books, accessed June 16, 2022, penguin.com/ibrahim-ahmad-executive-editor/; Famously, Marlon James, who won the Man Booker prize in 2015 for his novel A Brief History of Seven Killings, saw the manuscript for his debut novel John Crow’s Devil rejected 78 separate times by publishers before Akashic published it in 2005. Mark Brown, Matthew Weaver, “Man Booker’s debut novel rejected nearly 80 times,” The Guardian, October 14, 2015, theguardian.com/books/2015/oct/14/man-booker-prize-marlon-james-debut-novel-rejected-nearly-80-times was spurred in part by his belief that the industry was changing and that larger publishers increasingly recognized that authors of color can be both highly acclaimed and commercially successful. “What speaks loudest in this business and in any business are dollars,” he said. “When publishers see that writers of color can sell huge quantities of books, they will invest in those books.”55PEN America interviews with Ibrahim Ahmad, May and September 2021

“I’ve been in the publishing industry for over 10 years,” said Milena Brown, marketing director at PRH imprint Doubleday,56Milena Brown. (n.d.) Experience, LinkedIn, accessed July 31, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/in/milena-brown-3862416/ “and literally, this year has been the most action I’ve seen on this issue. It’s slow-moving, and that’s not great, but . . . talks of diversity don’t matter until there’s people of color at decision-making positions. Why is there a lack of diversity at the top?. . . I think people are starting to see things changing in the industry or in corporate America, period.” Brown adds that the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests helped empower her personally. “I started to be more vocal” about problems in the industry like inequities in pay, budgets, and advances. Ultimately, she predicts, “this is no longer going to be a trend” that lasts for a few months or a year, then reverts to “the same things we’ve been doing. I don’t think we are going to allow it anymore. We can now hold companies accountable.”57 PEN America interviews with Milena Brown, April and September 2021

Carrie Bloxson, the Hachette Book Group’s chief diversity, equity, and inclusion officer, said that new industry standards like collecting and disclosing employee and contributor statistics ensure publisher “accountability” to authors, readership, and industry professionals. Comparing Hachette’s 2020 and 2021 diversity reports, Bloxson notes, “What was interesting about 2021, too, is that the largest percentage gain for staff diversity was at VP and above, which is really heartening to see.”58PEN America interviews with Carrie Bloxson, June and September 2021

Others are more skeptical. Speaking to PEN America in October 2021, Chris Jackson, publisher and editor-in-chief of PRH’s One World, said: “The last shred of naivete I have about publishing is that I think we have passed an inflection point. I don’t think we can go back to the way it was because there’s just too much evidence that books coming from writers of color work in the market.”59PEN America interviews with Chris Jackson, April and October 2021 But when PEN America followed up in the summer of 2022, he was less certain: “I may have believed this when the interview first took place,” he said, “but I don’t believe it anymore. I’m pretty convinced at this point that things can definitely go back to the way they used to be.”

A Brief Overview of the Industry and the Publication ProcessThe American trade publishing industry consists of a patchwork of presses—from PRH, the largest, which publishes over 15,000 print titles a year,60“The Book Lover’s Guide to Publishing,” PRH, accessed June 16, 2022, penguinrandomhouse.com/articles/the-book-lovers-guide-to-publishing-part-1-publishing-ephemera/#:~:text=Read%20below%20for%20the%20answers,15%2C000%20print%20books%20each%20year to micro-presses that publish only a couple a year. Trade publishers acquire, edit, produce, and distribute works of fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction, and journalism. Trade books, the largest publishing category, are intended for a general audience and are usually sold in bookstores and through other retail booksellers. Other publishing categories include academic, professional, and specialty. While children’s and young-adult books may have some different conventions, they are often considered part of the trade publishing industry. The Big Five trade publishers were known as the Big Six until 2013, when Penguin and Random House merged. In 2020, PRH announced plans to buy Simon & Schuster for more than $2 billion; the Justice Department has sued to stop the merger, citing antitrust concerns.61“Justice Department Sues to Block PRH’s Acquisition of Riva Publisher Simon & Schuster,” The United States Department of Justice, accessed June 16, 2022, justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-block-penguin-random-house-s-acquisition-rival-publisher-simon If the merger goes through, the moniker will become the Big Four. The industry’s center of gravity is in New York City, where all of the Big Five and many other publishers are based. The Big Five account for an estimated 80 percent or more of the domestic trade book market, with PRH books alone comprising roughly 37 percent.62Thad McIlroy, “What the Big 5’s Financial Reports Reveal About the State of Traditional Book Publishing,” Book Business, August 8, 2016, bookbusinessmag.com/post/big-5-financial-reports-reveal-state-traditional-book-publishing/. For additional numbers on publishing market percentages, see Amy Watson, “Share of adult hardcover and paperback bestseller positions held by leading publishers in the United States from 2019 to 2021,” Statista, February 3, 2022, statista.com/statistics/1234734/book-publishers-bestsellers-list-share/#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20Big%20Five,from%20independent%20publishers%2C%20than%20majors. Within the Big Five, each conglomerate operates numerous “imprints”—literary brands that make relatively independent decisions in acquiring books. PRH, for example, owns about 275 imprints, including Riverhead, Vintage, Viking, One World, Doubleday, and Pantheon, each of which has its own editorial team and sensibility.63“Imprints,” PRH, accessed August 1, 2022, penguinrandomhouse.com/imprints. “PRH Imprints,” PRH, accessed August 1, 2022, permissions.penguinrandomhouse.com/imprints.php Hachette Book Group owns Basic Books, Grand Central Publishing, BoldType, Little Brown, and more.64“Imprints,” Hachette Book Group, accessed August 1, 2022, hachettebookgroup.com/imprints/ Amistad, an imprint known for focusing on work by Black writers, is an imprint of HarperCollins, as is Ecco.65“HarperCollins Imprint and Lines,” HarperCollins Publishers, accessed August 1, 2022, harpercollins.com/pages/corporate-harpercollins-imprints Simon & Schuster’s imprints include Atria, Scribner, and Avid Reader Press,66“Divisions and Imprints,” Simon & Schuster, accessed August 1, 2022, about.simonandschuster.biz/divisions-and-imprints/ while Macmillan’s include Flatiron Books, Henry Holt, and Farrar Straus and Giroux.67“Our Publishers,” Macmillan Publishers, accessed August 1, 2022, us.macmillan.com/publishers/ In all, the Big Five have an estimated 500-plus imprints,68https://aspiringauthor.com/publishers/publishing-houses-in-new-york/ many of which were once autonomous companies. Agents can submit a manuscript for consideration to multiple imprints within a publishing house, and imprints can bid against one another as long as a different publisher is also in the running. In contrast to the Big Five, independent publishers are not part of a large conglomerate. They tend to be much smaller and include the likes of Grove Atlantic, Graywolf, Beacon, New Press, Akashic, Feminist Press, and Catapult. With fewer resources, independent and small presses offer lower advances and slimmer marketing and publicity budgets. They are seen within the industry as taking greater creative risks and being less profit-focused, with some of them embracing a nonprofit model. While independent and Big Five publishers often act as competitors, they also have collaborative relationships, as major publishers frequently operate as distributors for one another and for books published by their indie counterparts. Though every publisher has its own processes, most houses have editorial, marketing, publicity, sales, and production departments. Other departments include art and design, contracts and legal, digital production, finance, and subsidiary rights.

The Publication ProcessThe first step of the process happens outside the publishing houses: when a writer with a manuscript or a book proposal queries an agent, or an agent queries a writer whom they hope to represent. Once they sign a representation agreement, the agent, who has developed relationships with editors at various houses, pitches the book project to editors. If an editor is interested in acquiring a book, they—often with the sales director—create a profit-and-loss projection that can include information such as production and manufacturing costs, royalty rate, formats, expected price, and, perhaps most important, expected sales. This sales projection is typically based on comparative titles (“comps”), previously published books that are similar to the proposed project and likely to appeal to the same book-buying audience. The final decision on whether to acquire is typically made through a committee that includes editorial, publicity, marketing, sales, and sometimes other departments, depending on the house. The advance is the amount the author is paid to write the book (with the agent taking a cut, usually 15 percent). It is based in part on sales projections, which in turn are based on the comp titles. As the word suggests, an advance is not simply a lump-sum payment. It is a preliminary payment of the author’s predicted future earnings—that is to say, the royalties from sales, share of any licensing agreements, and any other profit the author is are expected to make on the book. Advances are typically paid out in three or four installments: the first payment upon signing the contract, the second payment when the full manuscript is delivered, and subsequent payments when the book is published (including publication in different formats, i.e. hardcover and paperback). A writer starts receiving royalties on copies sold only once they “earn out,” meaning they have sold enough copies that their total royalties (and other earnings) exceed their advance. Marketing and publicity departments work together to ensure that the book finds an audience. Generally, marketing works on positioning a book: What genre is it? What social media campaigns should they run? What kind of advertising will the publisher run and on which platforms? How should the book be described and tagged for search engines? Publicists are responsible for soliciting “earned” media coverage (as opposed to advertising) of a book. They ensure that the book is reviewed and that the author is interviewed or featured in print or on radio, podcasts, or television. Publicists also plan and execute book tours, readings, and other events. With the marketing department, the salespeople are often responsible for managing direct relationships with bookstores and booksellers. Sales reps are a direct link to buyers—bookstores, other businesses, libraries, schools—and are responsible for selling the book to these purchasers. For each publishing “season”—often spring, summer, and fall—a house has an internal “launch” of its new books, during which editors present them to marketing and publicity teams and to national sales reps, aiming to get them excited about promoting the latest titles. Internal launches of a book take place about a year before it is set to be published.69See e.g. Kelly Notaras, A Publishing Timeline for First Time Authors, KN Literary Arts, June 27, 2017, last updated July 9, 2019, knliterary.com/a-publishing-timeline-for-first-time-authors/ After the launch, publishing houses host sales conferences, where marketing and publicity present a selection of the biggest upcoming titles—and associated highlights and tactics—to all the sales field reps. The marketing and publicity budgets are set during meetings that take place shortly after the launch presentations. Staff from editorial, marketing, and publicity are likely to be present. Also present for these deliberations might be sales managers who work with booksellers (representing, for example, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, Costco, and independent distributors). They consider how many copies were purchased from distributors in the past for similar books and discuss sales projections, leading to decisions on how much to spend to push a particular book to the market. The number of copies the publisher plans to publish—the so-called announced first print run (AFP), or announced market distribution (AMD)—is a key indicator of how big the house expects the book to be, and therefore how much of an investment it makes in marketing. If a book receives good early buzz, the AFP may increase and the associated marketing and publicity budgets may rise. The budget size also ties into the size of the author’s advance—a higher advance generally demands a higher budget to earn back that money. Distribution is broadly divided into print and e-book arms. Typically, big publishers possess in-house distribution services with their own sales representatives and warehouses. Most small and medium-sized publishers contract with a book distributor, which agrees to get their books to market (bookstores, book chains, online booksellers, and book wholesalers) in exchange for a percentage of sales. One of the distributor’s main roles is to handle advanced sales of a book to bookstores and libraries before it’s published. Distributors also commonly provide services including marketing, sales, logistics, shipping, order fulfillment, warehousing, and returns. Traditionally, when a book comes off the printer, it is sent to an established book distributor that provides warehousing for the book before it is sold to various stores in the book trade or to a wholesaler (such as Ingram, Baker & Taylor, or Greenleaf), which can also fulfill book orders from bookstores and libraries. There are several companies that operate purely as book distributors. Three of them—the Independent Publishers Group, Ingram Publishers Service, and National Book Network—collectively represent 900 small publishers.70Jim Milliot, “Where Have All the Midsize Book Publishers Gone?” Publishers Weekly, October 1, 2021, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/87526-where-have-all-the-midsize-book-publishers-gone.html But small publishers frequently work with one of the Big Five publishers to distribute and sometimes market their titles to bookstores and other sellers.71“Distribution: Inside Publishing,” Writers Services, accessed August 1, 2022, writersservices.com/resources/distribution-inside-publishing;”Demystifyig Book Distribution for Small to Mid-Sized Publishers,” Ingram Content Group, June 26, 2018, ingramcontent.com/publishers-blog/demystifying-book-distribution-for-small-to-mid-sized-publishers. |

Section II: Staff Diversity

The disproportionate whiteness of the publishing industry is a product of racial disparities that have dominated every professional field in America. But as other industries have made progress in diversifying, one reason that book publishing has lagged is that it “attracts people who don’t need to make money,” said consultant Richard Nash, who formerly headed Soft Skull Press, an independent publisher known for experimental fiction.72“About/Contact.” Richard Nash, accessed July 31, 2022, rnash.com/about/; “About,” Soft Skull Press, accessed July 31, 2022, softskull.com/about-us/.

Publishing is notorious for low pay and long hours and is centered in New York City, all of which pose barriers for those who do not have external sources of financial support from their families or savings. These limitations do not hinder people of color alone, but they do tilt the playing field toward people with wealthy families or powerful connections. Because people of color are more likely to lack these advantages, ostensibly race-neutral conditions like low entry-level salaries enshrine systemic inequities. “It’s very, very hard for somebody who is not independently wealthy to come into the industry and accrue the power that’s required to actually be the decision-maker later on,” said Elizabeth Méndez Berry of One World.73PEN America interviews with Elizabeth Méndez Berry, May and October 2021

The Numbers Tell the Story

Although there are few publicly available numbers that break down the ethnic and demographic makeup of publishing employees, the numbers we do have affirm what numerous interviewees told PEN America: that the publishing industry remains whiter than American society overall.

In 2015, Lee & Low Books, a children’s publisher, and researchers at St. Catherine University took the first publicly available baseline survey measuring diversity in the publishing industry as a whole.74Sarah Park Dahlen, Nicole Catlin, “Where is the Diversity in Publishing? The 2015 Diversity Baseline Survey Results,” Lee & Low Books, January 26, 2016, blog.leeandlow.com/2016/01/26/where-is-the-diversity-in-publishing-the-2015-diversity-baseline-survey-results/ Among the findings:

- The publishing industry was 79 percent white

- Executives in the publishing industry were 86 percent white

- Editorial departments were 82 percent white

- Sales departments were 83 percent white, and marketing and publicity departments were 77 percent white

- Book reviewers were 89 percent white

Lee & Low completed a follow-up survey in 2019, the most recent year for which data is available.75“Where is the Diversity in Publishing? The 2019 Diversity Baseline Survey Results,” Lee & Low Books, January 28, 2020, blog.leeandlow.com/2020/01/28/2019diversitybaselinesurvey/ Among the findings:

- The publishing industry was 76 percent white—but the 3 percent difference from the 2015 results “did not meet the bar for statistically significant change”

- Executives in the publishing industry were 78 percent white;

- Editorial departments were 85 percent white, a statistically insignificant increase from 2015

- Sales departments were 81 percent white, and marketing and publicity departments were 74 percent white

- Book reviewers were 80 percent white, and literary agents were also 80 percent white

While the 2019 survey appeared to show a slight improvement in diversity at the top levels, editorial departments were, the survey’s authors noted, “even more White than before.” The authors concluded that, overall, “the field is just as White today as it was four years ago.”76Where is the Diversity in Publishing? The 2019 Diversity Baseline Survey Results,” Lee & Low Books, January 28, 2020, blog.leeandlow.com/2020/01/28/2019diversitybaselinesurvey/

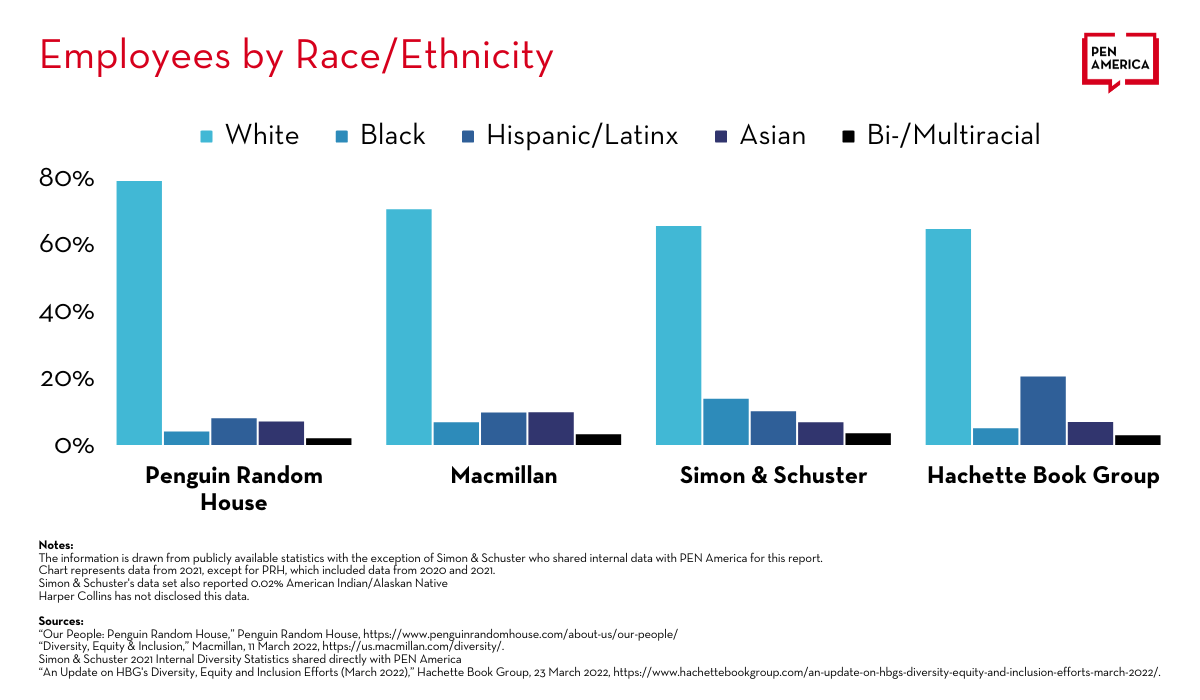

In the past couple of years, three of the Big Five houses—PRH, Macmillan, and Hachette Book Group—have published their own internal diversity statistics. PEN America has analyzed these reports and compared their findings. The percentage of white employees differs somewhat, although not massively, among the three houses: PRH’s employees are 74 percent white,77As of 2021. 2021-2022 Penguin Random House Social Impact Report, available at https://tinyurl.com/y69b8skp Macmillan’s 70.5 percent white,78As of 2021. Macmillan Publishers, Diversity Equity and Inclusion, https://us.macmillan.com/diversity and Hachette’s 64.6 percent white.79As of 2021. Hachette Book Group, An update on HBG’s diversity, equity and inclusion efforts (March 2022), https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/an-update-on-hbgs-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-efforts-march-2022 PRH, Macmillan, and Hachette also disclosed the makeup of their senior management teams. The data indicates that senior managers are disproportionately white, surpassing the percentage of white employees in lower positions.802021-2022 Penguin Random House Social Impact Report, available at https://tinyurl.com/y69b8skp; Macmillan Publishers, Diversity Equity and Inclusion, https://us.macmillan.com/diversity; Hachette Book Group, An update on HBG’s diversity, equity and inclusion efforts (March 2022), https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/an-update-on-hbgs-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-efforts-march-2022

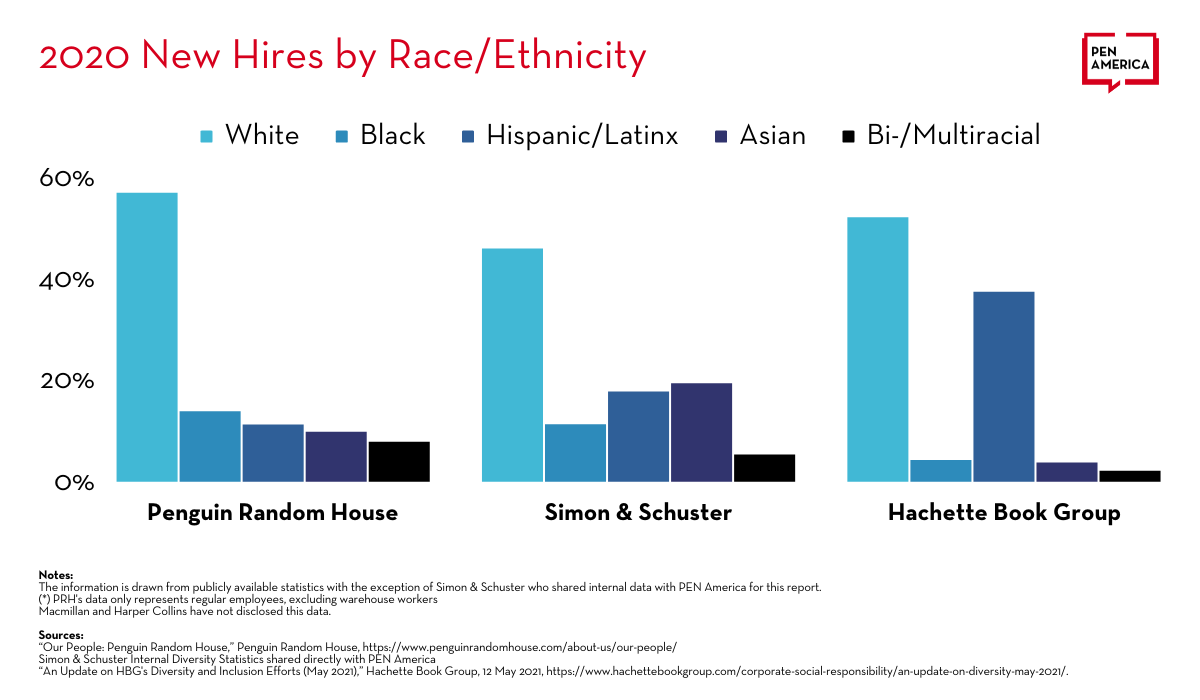

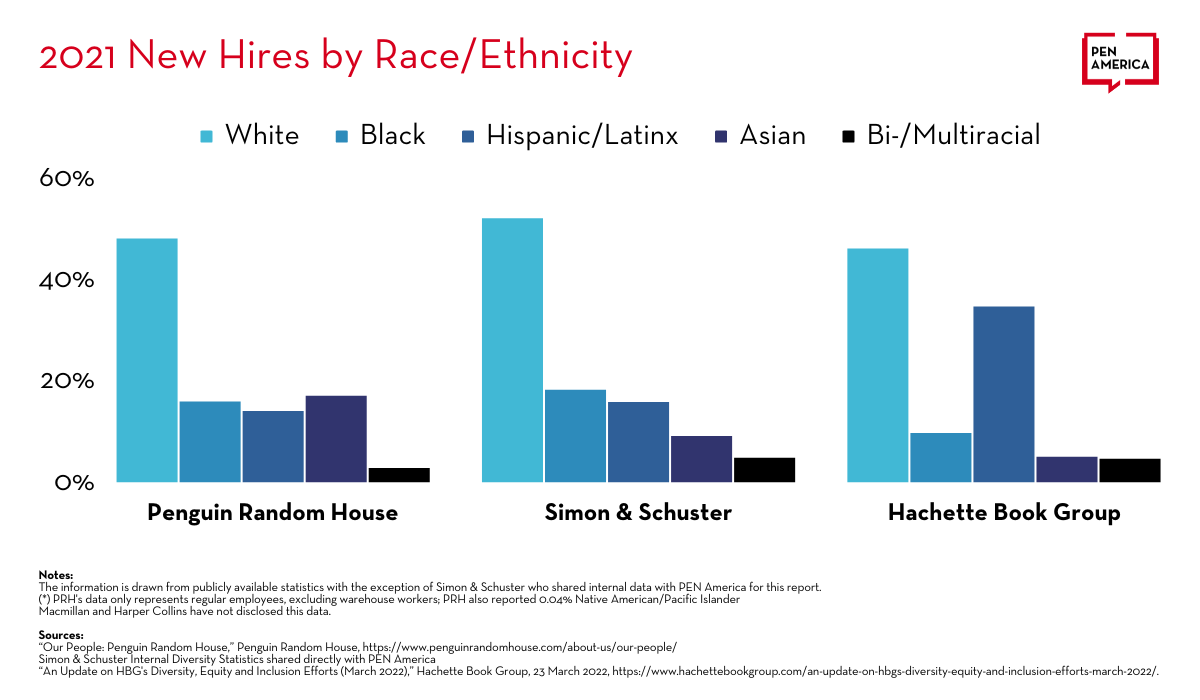

Of the five publishing houses, only PRH and Hachette Book Group have publicly disclosed the race and ethnicity of their new hires from the past two years; Simon & Schuster provided PEN America with internal reports from 2020 and 2021 that give this information. The numbers demonstrate that the efforts to increase diversity within the companies has resulted in more hires from underrepresented groups.

All of this data helps to confirm the widespread assumption that the industry remains overwhelmingly white, particularly at the higher echelons. Still, publishers’ decisions to release this information publicly is itself encouraging, as it provides a benchmark against which further progress can be measured.

A Rising Cohort of Publishers of Color

In the past few years, major publishing houses have begun aggressively courting professionals of color.81Alexandra Alter, Elizabeth A. Harris, “In Publishing, ‘Everything Is Up for Change’,” The New York Times, July 15, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/07/15/books/book-publishing-leadership.html Veteran publisher Erroll McDonald82“Erroll McDonald,” PEN America, accessed July 31, 2022, pen.org/user/erroll-mcdonald/ noted in 2021 that “more people of color have been appointed to senior positions in publishing in the last year than have been appointed in decades.”83“[Virtual] PEN Presents: Beyond Representational Politics in Publishing,” PEN America, October 4, 2020, pen.org/event/pen-presents-beyond-representational-politics-in-publishing/ Notably, many of these professionals have come from outside the publishing industry.84Ibid, “[Lisa] Lucas and [Dana] Canedy, both newcomers to publishing, are now poised to become two of the most powerful Black women in the literary world, with the ability to alter the culture of the divisions they lead and shape the landscape…[Chris] Jackson said that the scarcity of Black executives in publishing makes it hard for companies to recruit from within their own ranks and imperative that they look to other industries when hiring.”

Several of these hires or appointments have been to roles specifically focusing on organizational diversity, equity, and inclusion, including:

- In January 2021, Hachette hired Carrie Bloxson, former VP of marketing at HarperCollins but more recently the interim CEO of DoSomething.org, as head of diversity and inclusion85“Carrie Bloxson joins Hachette Book Group as Vice President, Diversity and Inclusion,” Hachette Book Group, January 7, 2021, hachettebookgroup.com/hachette-book-group-news/carrie-bloxson-joins-hachette-book-group-as-vice-president-diversity-and-inclusion/

- In September 2020, HarperCollins hired Gisselda Nuñez, former executive director and head of diversity strategy at Morgan Stanley, as its newly created VP of DEI86John Maher, “HC, S&S Name Company-Wide Diversity Executives,” Publishers Weekly, September 16, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/people/article/84348-hc-s-s-name-company-wide-diversity-executives.html

- In September 2020, Simon & Schuster appointed Amanda Armstrong-Frank as its director of workplace culture and diversity initiatives87Ibid.

Throughout 2020 and after, major publishing houses and other literary institutions also announced a series high-profile senior Black and Latinx editorial hires, among them:

- In April 2020, Nadxieli Nieto, a board member of Latinx in Publishing who formerly served as program director of the PEN America Literary Awards, joined Flatiron as executive editor88“Nieto Joins Flatiron,” Publishers Weekly, April 8, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/newsbrief/index.html?record=2663

- In July 2020, Lisa Lucas, formerly executive director of the National Book Foundation, was hired as publisher of Pantheon and Schocken Books, two PRH imprints89Calvin Reid, “Lisa Lucas to Head Pantheon and Schocken Books,” Publishers Weekly, July 15, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/83857-lisa-lucas-to-head-pantheon-and-schocken-books.html

- Also in July 2020, Krishan Trotman, formerly an executive editor at Hachette, started a new Hachette imprint focused on underrepresented voices called Legacy Lit90“Meet Legacy Lit,” Grand Central Publishing, accessed July 31, 2022, grandcentralpublishing.com/landing-page/meet-legacy-lit/

- In September 2020, Jamia Wilson, previously the director and publisher of CUNY’s Feminist Press, was named an executive editor at Random House91Calvin Reid, “Jamia Wilson Named Executive Editor at Random House,” Publishers Weekly, September 30, 2020, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/people/article/84486-jamia-wilson-named-executive-editor-at-random-house.html

- In 2020 and 2021, Dana Canedy, LaSharah Bunting, and Aminda Marqués González—all female journalists of color—joined Simon & Schuster. Canedy, a former administrator of the Pulitzer prizes and New York Times journalist, joined as senior vice president and publisher of the Simon & Schuster imprint92Jonathan Landrum Jr., “Dana Canedy named as publisher at Simon & Schuster,” The Washington Post, July 6, 2020, washingtonpost.com/business/dana-canedy-named-as-publisher-at-simon-and-schuster/2020/07/06/74b77eec-bfd5-11ea-8908-68a2b9eae9e0_story.html Bunting, a former New York Times editor and director of journalism at the Knight Foundation, joined as vice president and executive editor93“LaSharah Bunting, Vice President and Executive Editor,” Simon & Schuster, accessed July 31, 2022, simonandschusterpublishing.com/simonandschuster/lasharah-s-bunting.html. Marqués González, the first Hispanic person and second woman to serve as editor of the Miami Herald, also joined as a vice president and executive editor94“Mindy Marqués Joins Simon & Schuster Editorial,” Simon & Schuster, October 29, 2020, about.simonandschuster.biz/news/mindy-marques/. In July 2022, exactly two years from the date of her hiring, Canedy announced that she was leaving Simon & Schuster, reportedly to focus on writing95John Maher, “Dana Canedy to Step Down at Simon & Schuster,” Publishers Weekly, July 19, 2022, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/89892-dana-canedy-to-step-down-at-simon-schuster.html.

- In February 2021, author, editor, and host of the Minorities in Publishing podcast Jennifer Baker joined Amistad Books, the HarperCollins imprint, as senior editor. In September 2022, Baker revealed on Twitter that her position had been dissolved96@jbakernyc, Sep. 12, 2022, https://twitter.com/jbakernyc/status/1569332752889028608

- In March 2021, Yahdon Israel, former editor-in-chief of Brooklyn magazine and founder of the book club Literary Swag, joined Simon & Schuster as a senior editor97“About.” Literary Swag Book Club, accessed July 31, 2022, literaryswagbookclub.com/about; “Yahdon Israel Joins Simon & Schuster Editorial,” Simon & Schuster, March 22, 2021, about.simonandschuster.biz/news/yahdon-israel/; see also nytimes.com/2017/10/27/nyregion/how-yahdon-israel-of-literaryswag-spends-his-sundays.html

- In August 2021, Denne Michele Norris was named editor-in-chief at Electric Literature, reportedly making her the “first Black and openly trans editor-in-chief of a major U.S. literary publication”98Sophia Stewart, “Denne Michele Norris Takes the Helm at Electric Literature,” Publishers Weekly, publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/people/article/87087-denne-michele-norris-takes-the-helm-at-electric-literature.html.

- In December 2021, former New York Times reporter Adenike Olanrewaju joined HarperCollins as executive director99“Adenike Olanrewaju Joins Harper as Executive Editor,” Publishers Weekly, December 2, 2021, publishersweekly.com/pw/newsbrief/index.html?record=3524

- In February 2022, Milena Brown, formerly the associate director of marketing at Simon & Schuster, joined Doubleday, part of PRH, as marketing director100Milena Brown. (n.d.) Experience, LinkedIn, accessed July 31, 2022, linkedin.com/in/milena-brown-3862416/

- In February 2022, Retha Powers, former assistant director at the CCNY Publishing Certificate Program at City College, joined Henry Holt & Co. as vice president and executive editor101Retha Powers. (n.d.) Experience, LinkedIn, accessed July 31, 2022, linkedin.com/in/rethapowers/.

- In July 2022, Carmen Giménez, a queer Latinx poet and editor, was named director of the independent Graywolf Press102Claire Kirch, “Carmen Giménez named Graywolf Press Publisher,” Publishers Weekly, July 7, 2022 publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/89792-carmen-gimenez-named-graywolf-press-publisher.html

While laudable, this recent wave and the many appointees from other fields highlight the long-standing lack of a hiring pipeline for professionals of color. Speaking to PEN America, One World Editor-In-Chief Chris Jackson asks: “Why is it that these publishing houses have had to look outside to be able to hire diversely at the highest levels? They have not cultivated anyone within the industry to take on these roles.” Compounding his frustration, Jackson said, is “the self-congratulation that they hire people from outside the industry, when in fact that’s a damning fact about their failure.”

Jackson, a leading light of the industry who has edited and published such luminaries as Ta-Nehisi Coates, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ibram X. Kendi, Heather McGhee, Eddie Huang, and Bryan Stevenson, described himself as part of a previous wave of entry-level diversity hires in the early 2000s, “a whole generation of people that were hired at the same time that were close-knit, young people in publishing.” Many of those hires have since left the industry, he said, “because it was a hostile environment for them.”103PEN America interviews with Chris Jackson, April and October 2021. Their pain ripples far beyond their own dismal on-the-job experiences, to the future authors never published, colleagues never mentored, and stories never read.

Today, editors of color may worry that this cycle threatens to repeat itself, with editors of color who are brought in but then not supported. Jennifer Baker, the former senior editor at Amistad, critiqued her former employer on Twitter when sharing the news of her firing in late 2022: “I’m mostly dismayed at how the authors I worked with have been disregarded . . . And I remain upset at this treatment of creators of color when they were assured Amistad was a safe home for them/their work.”104@jbakernyc, Sep. 12, 2022, https://twitter.com/jbakernyc/status/1569332752889028608

Narrow pipelines for people of color

When Retha Powers was a Howard University undergraduate, she rode a train from New York City to Washington, D.C., and observed a Black woman reading The New York Times Book Review. She asked the woman if she could borrow it, struck up a conversation, and “by the time I got to D.C., she had offered me an internship.” The woman was Marie Dutton Brown, an editor and book agent with more than 40 years’ experience in publishing.105For more on Marie Dutton Brown’s impact and career, see e.g. Morgan Jerkins, “How Marie Dutton Brown Changed The Literary World,” Shondaland, December 18, 2017 shondaland.com/inspire/books/a14428057/marie-dutton-brown-profile/ Today Powers is a vice president and executive editor at Henry Holt & Company.106“Publishing Certificate Program,” the City College of New York, January 16, 2019, ccny.cuny.edu/english/pcp; Retha Powers. (n.d.) Experience, LinkedIn, accessed July 31, 2022, linkedin.com/in/rethapowers/.

Powers’s story is a testament to the importance of person-to-person connections and mentors in publishing. Yet the lack of such relationships is among the major obstacles cited by interviewees that narrow and obstruct the paths to publishing success. Historically, the field has drawn heavily from elite schools that themselves disproportionately recruit young people from privileged backgrounds, replicating broad inequities of both class and race. “Publishing is a very cliquish, network-y, elitist sort of group,” said literary agent Ayesha Pande, who worked as an editor from 1990 to 2005 and today runs her own literary agency with an explicitly anti-racist mission. “They all know and talk to each other, and when people are hiring, they ask each other: ‘Do you know someone?’ ‘Oh yes, my lovely Dartmouth assistant . . . ’ So that absolutely ensures that they stay within the group, within those elite circles.”107PEN America interviews with Ayesha Pande, March and September 2021

Like the clubby who-you-know phenomenon, other circumstances that may not code as race-based can hinder the progress of would-be publishers of color. In addition to her position at Holt, Powers was until recently the assistant director of City College of New York’s publishing program, started in 1988 by the biracial novelist Walter Mosley to develop a pipeline of publishing employees of color. Powers said that many of the students of color who graduate from the program are a few years older than typical entry-level publishing hires and sometimes have to contend with comments about “being old”—which, Powers said, “on its own might not sound like a microaggression in the sense that it’s not a direct comment about race, but it ultimately ends up being one.” Rather than sauntering from Ivy to Big Five, such students often have to spend years transitioning to publishing or, given the low salaries, take a second job to make ends meet.108PEN America interview with Retha Powers, May and October 2021

A master’s degree in publishing and experience in bookselling were initially not enough for Ebony LaDelle to land a full-time job. “I worked at Howard, at the bookstore, and then I worked there even after I graduated,” said LaDelle, who until this spring held the post of marketing director at PRH.109Ebony LaDelle. (n.d.) Experience, LinkedIn, accessed July 31, 2022, linkedin.com/in/ebonyladelle/ “So I had those few years of publishing-related experience, no different from anyone who is a part-time bookseller in a New York bookstore and got a job as an editorial assistant, which I saw happen all the time.” She remembers going on several interviews that did not lead to job offers: “They felt like I was great, but there were always these reasons why they went with another candidate.”110See also Linda Duggins, Tracy Sherrod, Erroll McDonald, Cherise Fisher, Janifer Wilson, Kori Wilson, Kerri K. Greenidge, Ebony LaDelle interviewed by Alexandra Alter, Elizabeth A. Harris, Joumana Khatib, Concepción de León, “ ‘A Conflicted Cultural Force’: What It’s Like to Be Black in Publishing,” The New York Times, July 1, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/07/01/books/book-publishing-black.html After several such dead ends, LaDelle reluctantly enrolled in a masters program at Pace University, but still struggled with finding a job after she graduated. One conversation there stuck with her and helped her process her earlier struggles. “Someone said to me something I’ll never forget: that at the end of the day, the people are just thinking about who they could see themselves getting drinks with. And it’s a slight to yourself, but I do think that they’re looking for who they unconsciously feel most comfortable with, and it seems like more often than not, that’s a white candidate.”111PEN America interviews with Ebony LaDelle, May and September 2021

Zakiya Dalila Harris is the author of the satirical novel The Other Black Girl, a 2021 New York Times bestseller about a young Black woman who contends with racism in the publishing industry.112“The Other Black Girl,” Simon & Schuster, accessed July 31, 2022, simonandschuster.com/books/The-Other-Black-Girl/Zakiya-Dalila-Harris/9781982160142 While the book is wider ranging, Harris said that she did draw from her own experience feeling like “the only one” during her nearly three years at Knopf/Doubleday as an editorial assistant and assistant editor.113PEN America nterviews with Zakiya Dalila Harris, July and September 2021; see also Elizabeth A. Harris, “Her Book Doesn’t Go Easy on Publishing. Publishers Ate It Up.” The New York Times, May 23, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/05/23/books/zakiya-dalila-harris-other-black-girl.html She saw that most hires had personal connections to the hiring editor, had gone through Columbia’s publishing program—with its high cost as a barrier to entry—or had passed through circles that Harris saw as closed and essentially white. Always in the back of her mind was the idea that she was the sole Black editorial assistant. “I definitely had the thought that this wasn’t the path for me,” she recalled, but remembered thinking, “If I can’t make this work, and I’ve had all these opportunities afforded to me—an MFA, resources, availability of financial help—how hard must it be for someone else to get hired here?”114PEN America interviews with Zakiya Dalila Harris, July and September 2021

These hiring disparities translate into author disparities. Several insiders reported that employees who feel personally connected to a book help generate excitement for it that builds into greater support within the publishing house and in the marketplace. In this way, the composition of the workforce directly translates into whose stories get told and whose don’t.

In PEN America’s conversations with representatives of the Big Five houses, executives emphatically touted their initiatives and policies aimed at disrupting this cliquishness, such as internship, associate, and mentorship programs. But even if these efforts succeed, they will take time, and sustained commitment, to bear fruit. Decades of exclusionary hiring and retention failures mean that there are comparatively few mid-career or late-career professionals of color to mentor this rising generation or wield authority in pushing for greater inclusion. If so many of Chris Jackson’s peers hadn’t felt the need to defect, they could now be filling these voids.

Employee Retention and Promotion

Beyond hiring, several publishing conventions limit the pathways for upward mobility, making it difficult for younger people to graduate into positions of power. “Some places have faced retention issues on the junior level because advancing is so difficult,” said Yuka Igarashi, executive editor at Graywolf. “There’s this convention that people stay editorial assistants for three years, and I’ve heard people repeat that so many times to me. There are other weird publishing conventions, like that you need to do the job for a year before you’re acknowledged for the title, which leads to back promotion.”115PEN America interviews with Yuka Igarashi, May and October 2021 These conventions do not uniquely affect publishing professionals of color. Yet combined with the scarcity of people of color already at the top, they function to inhibit the advancement of employees of color and keep the decision-makers in the industry disproportionately white.

Interviewees stress that low turnover at the higher, whiter levels can mean less room for high-level, non-white executives to make changes, execute new ideas, and help promote longer career trajectories for staff of color. Lisa Huang, a sales strategy associate at Macmillan, said: “I feel like because a lot of people in the industry have retained their jobs for 10-plus years, and back then the publishing industry was like 90 percent white . . . , everyone knows each other, so of course everyone is going to vouch for each other for promotion. And because a lot of the younger positions are more diverse than the older positions, we don’t get as many connections and networking to aim for those promotions.”116PEN America interview with Lisa Huang, May 2021

Carrie Bloxson of Hachette believes that the need for greater opportunity is “urgent” and that given the slow rate of turnover, “we may need to consider some additional options if we want to see change faster.” Bloxson asks: “Is there room to consider additional roles within the industry? I realize that’s challenging in terms of budget, but that could be a serious gamechanger in terms of opening the pipeline.”117PEN America interviews with Carrie Bloxson, June and September 2021

The lack of upward mobility for younger employees leads some of them to leave the industry. “At one of the publishing houses that I worked at that was very highly respected and highly regarded, most of the senior members of that house died out of their job,” said Lesleigh Irish-Underwood, who worked in publishing for 25 years before leaving in 2013.118“Lesleigh Irish-Underwood,” Brooklyn Community Foundation, accessed July 31, 2022, brooklyncommunityfoundation.org/about/board-staff/lesleigh-irish-underwood. It’s hard, she said, for a young go-getter to be placed in a situation where they’re expected to work for decades without a clear path to seniority.119PEN America interviews with Lesleigh Irish-Underwood, June and September 2021