Building Resilience

Identifying Community Solutions to Targeted Disinformation

PEN America Experts:

Introduction

Disinformation as a Free Expression Issue

People need reliable information to participate fully in the democratic process. Particularly, they need it to choose their next elected representatives, assess policy and policy proposals both locally and nationally, and engage in civic discourse.

In recent years, however, the political information landscape has become increasingly fraught for voters: the rise of new disinformation vectors and theories, such as the “Big Lie” of election denialism, have caught hold in communities around the country. In conjunction, the collapse of local print and broadcast outlets has created new information vacuums, pushing readers toward new and not-always-trustworthy sources. Disinformation narratives often exploit the information gaps left by shuttered local news outlets and gain traction in informal information channels outside of legacy news media, such as social media messaging apps, religious groups, and in-language (e.g., non-English) commercial radio stations.

When people encounter political information where they are not expecting it, Mimizuka explained, they are less prepared to consume it with a critical eye.

PEN America first articulated the threat disinformation poses to free expression and democracy in our landmark 2017 report, Faking News: Fraudulent News and the Fight for Truth. In the ensuing years, we have been at the forefront of engaging with the mainstream media, vulnerable communities, and tech platforms to better understand and respond to the threat. We have published additional research, developed a media literacy curriculum entitled “Knowing the News,” and launched a large-scale campaign to counter disinformation in the 2020 election. Over the past two and a half years, we have increasingly turned our focus to working with communities directly targeted by disinformation, and specifically with the community leaders and other trusted sources of credible information who are best positioned to foster resilience to efforts to mislead and deceive.

At the same time, we have remained engaged with policymakers and platforms to seek solutions to disinformation that do not themselves infringe on freedom of expression. And we have observed that the policy conversation around “solving” disinformation is sometimes insufficiently informed by the on-the-ground experiences of targeted groups. Yet PEN America’s disinformation work and research underscores a key dynamic: that disinformation spreads—and must be fought—at the community level.

To this end, PEN America has brought community members in hotly contested states together at town halls, public events, and private gatherings with local journalists, activists, local election officials, and other community leaders since 2020 to discuss what the election process looks like and build a broader understanding of—and resilience against—anticipated attempts to mislead the public. PEN America engaged directly with news leaders to discuss challenges in covering elections and reporting results, and how these could best be tackled without increasing the risk and role of disinformation.1“Hard News: Journalists and the Threat of Disinformation,” PEN America, last accessed May 4, 2023, pen.org/report/hard-news-journalists-and-the-threat-of-disinformation/

One major insight that emerged from PEN America’s work with these communities during the 2022 midterm election season is how disinformation efforts merge with broader antidemocratic narratives, xenophobic rhetoric, and simple “dirty politics.” Conspiracy theories like the “Great Replacement Theory” can be factually disproven and have been repeatedly debunked. But the racist scapegoating of immigrants and people of color and the anti-Semitic foundations upon which the conspiracy theory is built cannot be dismantled through a simple recitation of facts. False information about the COVID-19 virus can be debunked, but such disinformation relies on a distrust of the federal government and a feeling of alienation from one’s public officials—something that is more complicated to address.

In our conversations with community partners during the 2022 midterm election season, these blurred lines between specific disinformation campaigns and the broader narratives on which they relied came up again and again. Our partners underscored the need for a more comprehensive approach to disinformation, one that goes beyond simply debunking false stories and toward a more holistic approach of developing media and civic literacy.

This involves spotting disinformation in community spaces that are not typically viewed as vectors for political content. As Kayo Mimizuka, a graduate assistant researcher at the University of Texas at Austin’s Center for Media Engagement, explained of their work studying the spread of disinformation on apps like WhatsApp and WeChat, users “don’t see [these apps] as avenue[s] where they can get factual or trusted sources of news, but nevertheless they are exposed to political content or news, especially before the election. We see it as incidental exposure to political content and news, rather than them actively seeking political content.” When people encounter political information where they are not expecting it, Mimizuka explained, they are less prepared to consume it with a critical eye. They are also far less likely to publicly challenge disinformation on these channels, given that the false information may come from close friends, family members, or others it would be uncomfortable to challenge.

Sustained exposure to disinformation can have major consequences for individuals—and democracy at large. Voter apathy is another dynamic that stretches beyond disinformation, but that is inextricably linked to it. Election-related disinformation is not always intended merely to sway voters from one side to another or to depress the turnout of those supporting a specific candidate, but can also be intended to undermine trust in elections, mainstream institutions (the government, the media, appointed officials), and democracy itself. The more disinformation proliferates, the more pronounced the effect. As stated in a report from the Brookings Institution, “The explosion of misinformation deliberately aimed at disrupting the democratic process confuses and overwhelms voters.”2Gabriel R. Sanchez, Keesha Middlemass, and Aila Rodriguez, “Misinformation Is Eroding the Public’s Confidence in Democracy,” Brookings Institution, July 26, 2022, brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2022/07/26/misinformation-is-eroding-the-publics-confidence-in-democracy/ One of PEN America’s partners put it bluntly: “If people don’t understand how the system works, they don’t trust it.”3Maritza Félix, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 24, 2023.

It also works the other way: voters with low trust in mainstream institutions may be more likely to believe conspiracy theories that tell them their vote will not be counted, that elections are rigged, and that those reporting the facts are in fact lying to them.4Silvia Mari, Homero Gil de Zúñiga, Ahmet Suerdem, Katja Hanke, Gary Brown, Roosevelt Vilar, Diana Boer, and Michal Bilewicz, (2022), “Conspiracy Theories and Institutional Trust: Examining the Role of Uncertainty Avoidance and Active Social Media Use,” Political Psychology, 43, 2, May 14, 2021: 277–296. doi.org/10.1111/pops.12754 Alienation from the democratic process creates a receptive audience for disinformation, which creates further alienation—a vicious cycle of antidemocratic disempowerment.

Researchers tapped by the U.S. Senate to study Russian efforts to influence the 2016 presidential election concluded that the Kremlin’s propaganda was designed to “exploit societal fractures, blur the lines between reality and fiction, erode our trust in media entities and the information environment, in government, in each other, and in democracy itself.”5Renee DiResta, Dr. Kris Shaffer, Becky Ruppel, David Sullivan, Robert Matney, Ryan Fox, Dr. Jonathan Albright, and Ben Johnson, “The Tactics & Tropes of the Internet Research Agency,” New Knowledge at the Request of the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, December 17, 2018, int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/533-read-report-internet-research-agency/7871ea6d5b7bedafbf19/optimized/full.pdf#page=1 The normalization of disinformation is corrosive to democracy itself. Accordingly, tackling disinformation requires building up faith in democracy and its institutions, and strengthening media and disinformation literacy among communities whose faith in our democratic system is being deliberately targeted.

The purpose of this white paper is to share lessons learned from PEN America’s engagement with community partners who are working to tackle these important issues, during the 2022 midterm elections cycle and beyond, with the goal of informing broader efforts to build our collective resilience to disinformation.

Methodology

This white paper examines election disinformation narratives and resilience strategies in Miami and South Florida; Dallas–Fort Worth, Texas; and Phoenix, Arizona, particularly among communities disproportionately targeted by disinformation, including communities of color, non-native-English-speaking groups, rural communities, historically disenfranchised populations, and other marginalized communities.6Mark Kumleben, Samuel Woolley, and Katie Joseff, “Electoral Confusion: Contending with Structural Disinformation in Communities of Color,” Protect Democracy, June 2022, protectdemocracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/electoral-confusion-contending-with-structural-disinformation-in-communities-of-color.pdf; Erica Weintraub Austin, Porismita Borah, Shawn Domgaard, “COVID-19 disinformation and political engagement among communities of color: The role of media literacy,” Misinformation Review, March 8, 2021, misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/covid-19-disinformation-and-political-engagement-among-communities-of-color-the-role-of-media-literacy/; “A Growing Threat: The Impact of Disinformation Targeted at Communities of Color,” Hearing before the Committee on House Administration, Subcommittee on Elections, April 28, 2022, congress.gov/event/117th-congress/house-event/114642?s=1&r=4 It is based upon PEN America’s engagements with communities to build resilience against disinformation in these three locations, beginning in June 2022. In each location, PEN America has conducted in-person public meetings, panels, and town halls, private consultations and roundtables, and virtual gatherings both public and private. To produce this report, PEN America completed 10 follow-up interviews with leading partners from January to February of 2023. These conversations, observations, and recommendations are informed further by desk research, PEN America’s previous research on disinformation, and additional contacts with partners on the ground and in civil society.

Since 2020, PEN America has engaged in building community-level disinformation resilience and developed partnerships with individuals and organizations—including local and community journalists—engaged in addressing disinformation in their communities. As part of that work, we found these groups were largely focused on building and empowering healthy information ecosystems for their communities—especially related to elections and voting—as a key proactive strategy of disinformation defense. These individuals and organizations included in-language fact-checkers, advocacy organizations, journalism and communication schools, community media journalists, public libraries, nonprofit newsrooms, radio stations, legacy newsrooms, grassroots coalitions, faith leaders, organizers, educators, diaspora community organizations and centers, and voting rights and civil liberties organizations. This paper seeks to elevate the essential work of these leaders and community members and ensure those insights inform the larger national conversation regarding disinformation defense.

This white paper examines themes and narratives regarding disinformation that have emerged from work in each location and includes case studies highlighting one major disinformation dynamic in each state. It concludes by identifying priorities for efforts to build community resilience to disinformation during the upcoming 2024 election season.

Eduardo A. Gamarra speaks with CNN Español before a panel discussion in September 2022. Photo by Rodolfo Benitez

Florida

PEN America’s research and engagements in South Florida have specifically focused on the state’s diaspora communities and communities of color—groups disproportionately targeted by disinformation. About two-thirds of the population in Miami speak Spanish as their native and primary language.7Population Data for Miami-Dade County, Miami-Dade Matters, accessed May 4, 2023, miamidadematters.org/demographicdata?id=414§ionId=935 Our partners emphasize the diversity of the region’s Latino community, 35 percent of whom remain unaffiliated with a major U.S. political party.8Luis Noe-Bustamante, “Latinos make up a record 17% of Florida registered voters in 2020,” Pew Research Center, October 19, 2020, pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/19/latinos-make-up-record-17-of-florida-registered-voters-in-2020/

In an interview with PEN America, Wilkine Brutus, a radio reporter at WLRN, South Florida’s NPR-affiliate radio station, explained, “The political landscape here in South Florida is very multilingual and multiethnic, and so it’s very difficult to talk about politics in Florida without talking about the politics happening in other countries.”9Wilkine Brutus, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 19, 2023. Brutus further noted that knowledge of cultural context is critical when communicating with diaspora communities particularly: “The diaspora [in South Florida] is also consuming information from their particular country, merging that with how Americans interact with that information. . . . There’s a lot of context that can be extremely lost if our newsroom isn’t diversified enough to understand the complexities of people from different backgrounds.”

“The diaspora [in South Florida] is also consuming information from their particular country, merging that with how Americans interact with that information. . . . There’s a lot of context that can be extremely lost if our newsroom isn’t diversified enough to understand the complexities of people from different backgrounds.”

Wilkine Brutus

This dynamic is not limited to Florida’s Spanish-speaking communities. Johnson Ng, publisher of the United Chinese News of Florida, explained during a September 2022 event that one of his outlet’s top responsibilities is “to educate the Chinese community here on the U.S. political system as a two-party system.”10“Choosing Community: Toward a Civic and Informed South Florida,” PEN America, event on September 24, 2022, pen.org/event/choosing-community-toward-a-civic-and-informed-south-florida/ He noted that closed messaging apps that are highly utilized by Chinese diaspora communities in Florida and elsewhere, like WeChat, are key vehicles for disinformation alongside Chinese government propaganda.11Panel discussion with Johnson Ng. For more analysis of this issue, see e.g., Shen Lu, “Liberal Chinese Americans Are Fighting Right-Wing Disinformation on WeChat,” Foreign Policy, November 13, 2020, foreignpolicy.com/2020/11/13/liberal-chinese-americans-fighting-right-wing-wechat-disinformation/; Seth Kaplan, “China’s Censorship Reaches Globally Through WeChat,” Foreign Policy, February, 28. 2023, foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/28/wechat-censorship-china-tiktok/; Paul Mozur, “Forget TikTok, China’s Powerhouse App is WeChat, and Its Power is Sweeping,” The New York Times, September 4, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/09/04/technology/wechat-china-united-states.html

The need for more news sources and information about elections and other democratic processes to be translated into non-English languages, as well as the failure of media and other institutions to take into account the cultural contexts of immigrant and diaspora communities, emerged as two key gaps in the Florida media landscape. Ignoring cultural associations that some communities may have with particular symbols or phrases, for example, can lead to broken trust in the media purporting to serve them, inadvertently turning them towards alternative and less credible sources of information.

Key Partners

PEN America’s key partners in South Florida include:

- Venezuelan American Caucus, a Fort Lauderdale–based civic engagement organization serving Florida’s Venezuelan community

- Cubanos Pa’lante, a progressive organizing coalition based in Miami serving Florida’s Cuban community

- Factchequeado, an initiative serving Hispanic and Latino communities to counter mis/disinformation in Spanish

Through its engagements, PEN America also built a network of Florida-based local journalists, community organizers, and professionals working in community and ethnic media.

Pictured from left to right: Ana Sofia Pelaez, Wilkine Brutus, and Johnson Ng participate in a panel discussion in September 2022. Photo by Rodolfo Benitez

In multiple community consultations in Florida, participants noted that the mechanics of democracy (including elections)—and the threats to it—are simply not discussed enough in non-English language television and radio programs. This lack of discussion, exposure, and civics education can open a door for mis/disinformation about the functionality of American democracy, which diaspora communities are more likely to believe, our interviewees stressed, because they are using their home—often non-democratic—countries as their frame of reference.12See also Raquel Reichard, “How Republicans & Democrats Weaponize Latinx Trauma to Get Votes,” Refinery 29, November 11, 2021, refinery29.com/en-us/2021/11/10688253/latinx-voters-florida-democrats-republicans-socialism

Evelyn Pérez-Verdia, founder and chief strategy officer of We Are Más, and others PEN America consulted in July 2022’s roundtable repeatedly said that messaging about American politics and democratic processes—without appropriate appreciation of cultural context—can quite literally get lost in translation. For example, the word “progressive” is regularly used to describe a part of the American political spectrum and some American politicians. But in Spanish it translates as “progresista,” which for many of Cuban, Venezuelan, or Colombian origin has connotations with the communist or socialist regimes they fled.13Tim Padgett, “You say progressive, yo digo progresista: Losses divide Florida’s Latino Democrats,” WLRN, December 12, 2022, wlrn.org/politics/2022-12-12/you-say-progressive-yo-digo-progresista-losses-divide-floridas-latino-democrats Adelys Ferro, of the Venezuelan American Caucus, described “progresista” as a “bad” and “forbidden” word because these communities often associate it with a political ideology that “demonized anything related to equality, to justice, to human rights, to social rights, to civil rights.”14Adelys Ferro, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 18, 2023.

What’s glaring for us is the absence of our stories in the mainstream media, that our stories only percolate when there’s a crisis, so we are always viewed as a community in crisis, and that gets people very angry, makes people very isolated, and makes people even more vulnerable to believing the fake news and the misinformation out there.

Leonie Hermantin

According to PEN America’s partners, U.S. journalists and media outlets could do more to take these factors into consideration when reaching diaspora communities. It is also a factor that creates opportunities for purveyors of disinformation to leverage the historical and political traumas of specific diaspora communities. We explore this theme in more depth below.

During a public event in September 2022, Leonie Hermantin of the Haitian Community Center Sant La spoke about how underrepresentation of certain communities, in both the newsroom and media coverage—especially in legacy newspapers like the Miami Herald—can alienate communities and open doors for disinformation: “What’s glaring for us is the absence of our stories in the mainstream media, that our stories only percolate when there’s a crisis, so we are always viewed as a community in crisis, and that gets people very angry, makes people very isolated, and makes people even more vulnerable to believing the fake news and the misinformation out there.”15“Choosing Community: Toward a Civic and Informed South Florida,” PEN America, event on September 24, 2022, pen.org/event/choosing-community-toward-a-civic-and-informed-south-florida/

The Haitian Times, a community media outlet serving Haitian diaspora communities, aims to bridge the generational and geographical gaps among Haitians. The outlet plays a crucial role in the South Florida media landscape—and has had to navigate disinformation schemes targeting the paper itself. The Haitian Times regularly serves their readership by identifying, debunking, warning, and informing their readers about nefarious disinformation schemes, and works to empower its community of Haitian Americans with credible information needed to engage in U.S. politics and increase and celebrate Haitian American visibility in civic spaces.

Campaigns that target community media outlets like The Haitian Times risk undermining trust in an outlet that is essential to helping that community defend against disinformation. In the early months of 2023, The Haitian Times was the target of a scam related to the Biden Administration’s humanitarian parole immigration program, which initially served only Venezuelans but in January 2023 was expanded to include Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Cubans.16The White House, “Fact Sheet: Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Border Enforcement Actions,” January 5, 2023, whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/01/05/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-new-border-enforcement-actions/ The program requires those seeking humanitarian parole to have a U.S. sponsor, and scammers illegally charged Haitians hundreds of U.S. dollars to submit comments to The Haitian Times, which they said would match people with sponsors, a service The Haitian Times does not provide.17Roc Rejy Joseph and Onz Chéry, “Beware: The Haitian Times Targeted in Parole Scam,” The Haitian Times, March 8, 2023, haitiantimes.com/2023/03/08/biden-parole-program-scam/ Ashley Miznazi, then a Haitian Times reporter covering Haitian communities in the South Florida/Miami area, told PEN America that the outlet believes the scam spread through WhatsApp groups.18Ashley Miznazi, interview by Hannah Waltz, PEN America, April 27, 2023, phone call. In response, The Haitian Times not only reported on the schemes, but also created a hub on their website detailing the nature of the scams and offering recommendations for girding against them, and then directed readers to find reliable information on the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website.19“Slam the scams targeting Haitians,” last accessed July 5, 2023, haitiantimes.com/slam-the-scams-targeting-haitians/ The outlet has also highlighted that the community is targeted by a range of immigration, Ponzi, and day-trading schemes.20Macollvie J. Neel, “Recent fraud cases in US affecting Haitian communities,” The Haitian Times, March 15, 2023, haitiantimes.com/2023/03/15/recent-fraud-cases-in-us-affecting-haitian-communities/; “Common Scams,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, last accessed June 26, 2023, uscis.gov/scams-fraud-and-misconduct/avoid-scams/common-scams. Creole-language talk radio and YouTube channels, among other digital forums increasingly, are the primary vectors of scams and related disinformation, Miznazi noted, “And in the last few years they’ve really seemed to kick off.”21Ashley Miznazi, interview by Hannah Waltz, PEN America, April 27, 2023, phone call; Tim Padgett, “Why is disinformation obstructing a new U.S. parole program for Haitian migrants?,” WLRN, February 16, 2023, immigration/2023-02-16/why-is-disinformation-obstructing-a-new-u-s-parole-program-for-haitian-migrants. The Haitian Times has routinely responded by working to support their readers with the facts. Macollvie J. Neel, executive editor of The Haitian Times, told PEN America that support from “non-newsroom sources and the existence of community media like [The Haitian Times] are important in combating mis/disinformation when mainstream outlets can’t afford to.”22Macollvie J. Neel, conversation with Hannah Waltz, PEN America, July 5, 2023, email.

How Disinformation Purveyors Exploit Historical Traumas

Somebody feeds that trauma with lies . . . and you live in fear that someone is going to take your freedom away from you

Adelys Ferro

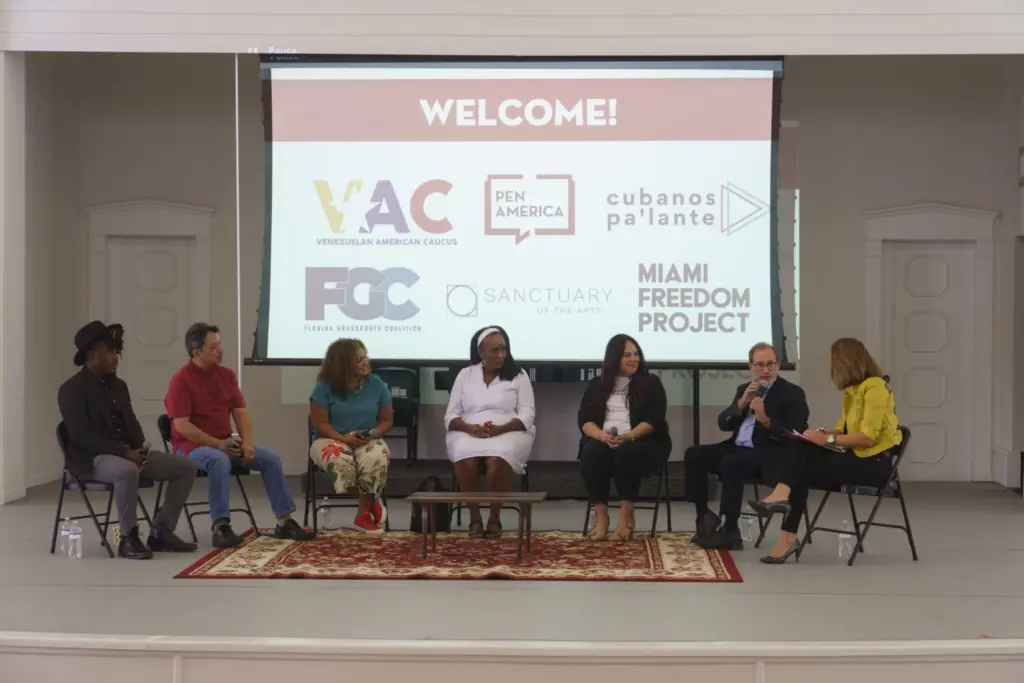

Panelists pictured from left to right: Wilkine Brutus, Johnson Ng, Tamoa Calzadilla, Leonie Hermantin, Cynthia Perez, Eduardo Gamarra, Evelyn Pérez-Verdia. Photo by Rodolfo Benitez

Many members of diaspora communities in South Florida have come to the U.S. from countries that have experienced authoritarian rule, dictatorships, and violent regimes, including Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. Ferro, of the Venezuelan American Caucus, notes that political messaging often capitalizes on these communities’ historical traumas, falsely equating American policy proposals with the same policies that victimized these communities in their former home countries. “If you get here with trauma and somebody feeds that same trauma with more lies that imply that you could live the same [way] in the United States . . . then your trauma just intensifies, and you live in fear that someone is going to take your freedom away from you,” Ferro stressed. “So that’s the biggest challenge with our diasporas.”

An example of this dynamic at play occurred during the 2020 election: the Trump campaign ran a Spanish-language advertisement in Florida days before the election that claimed Venezuela’s repressive socialist leaders supported Biden.23Salga a Votar, Donald Trump for President, accessed May 4, 2023, youtube.com/watch?v=BtA1i0ujGrQ The claim was parroted by various social media stories across Facebook and WhatsApp, saying that Biden had been endorsed by Venezuelan socialist president Nicolás Maduro.24Sabrina Rodriguez and Marc Caputo, “‘This is f—ing crazy’: Florida Latinos swamped by wild conspiracy theories,” Politico, September 14, 2020, politico.com/news/2020/09/14/florida-latinos-disinformation-413923 In fact, just a few weeks prior to the Trump ad, Maduro had said he saw “no difference” between Biden and Trump.25“Maduro: Venezuela no ve diferencias entre Trump y Biden,” Associated Press, September 29, 2020, apnews.com/article/noticias-3f466c3a80f12febdbb08898e5c2d142 This narrative seemed tailor-made to exploit the traumas of Floridians hailing from repressive socialist and communist regimes, and Venezuelan Americans in particular.26For additional reporting on this phenomenon see e.g., Raquel Reichard, “How Republicans & Democrats Weaponize Latinx Trauma to Get Votes,” Refinery 29, November 11, 2021, refinery29.com/en-us/2021/11/10688253/latinx-voters-florida-democrats-republicans-socialism; Paola Ramos, “As A Cuban American, I See A Story the Numbers Miss,” Vogue, November 6, 2020, vogue.com/article/cubans-miami-election-2020

Ferro, speaking to PEN America, insisted that while social media, WhatsApp, and television are all potential media for disinformation, “the real danger in Miami and South Florida is the radio.” The Miami Herald also recognized radio as a primary vector of disinformation and, in response, launched a partnership with Florida International University students called “Mic Check Miami,” which highlighted and debunked popular disinformation narratives on Spanish-language radio during the 2022 midterm election cycle.27Mic Check Miami, Miami Herald, last accessed May 4, 2023, miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/mic-check-miami Their database identifies particular political narratives, alongside what a reader or consumer of the narrative would need to know to understand the full context.28Monitoring Airwaves in Miami, Miami Herald, accessed May 4, 2023, airtable.com/shrRahIAXAeEMb59E/tbld4uLxXGbk6LDHt?backgroundColor=cyanLight&viewControls=on The Miami Herald then rates the civic impact of the narrative: a rating of Plus-3 means the content is “accurate, highly original material” and Minus-3 means it is “hateful, inciting, illegal, disinforming.” In this way, readers are able to evaluate whether a specific claim is accurate, misleading, or disinformation. In addition to disinformation narratives espoused by radio hosts themselves, researchers found that some radio show hosts “disseminate disinformation directly or indirectly by allowing callers and guests to freely repeat falsehoods or vituperation without challenge or counterpoint.”29Andres Viglucci, Joey Flechas, and Lesley Cosme Torres, “How partisan angst, conspiracies thrive in Miami’s Spanish-language media echo chamber,” Miami Herald, December 20, 2022, miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/mic-check-miami/article269058552.html

“Daily you will hear in one of these radio stations that former president Barack Obama is behind everything that is happening right now, that he’s the one that is handling all the situations with the Biden administration,” said Ferro. Spanish-language radio also disseminated conspiracy theories falsely accusing Dr. Anthony Fauci of colluding with pharmaceutical companies to promote COVID-19 vaccines in order to personally profit from vaccine sales.30Monitoring Airwaves in Miami, Miami Herald, accessed May 18, 2023, airtable.com/shrRahIAXAeEMb59E/tbld4uLxXGbk6LDHt?backgroundColor=cyanLight&viewControls=on

During the midterm election season, Ferro witnessed antagonistic attitudes of some Latin American immigrants in South Florida towards those trying to enter the country, dynamics that were supercharged by disinformation. She stated, “If there is something that I would like to leave in this recording session as the most painful, illuminating experience that I had . . . among brothers and sisters, even from the same countries, there is absolute rejection . . . [of] the [immigrants] that are arriving here right now, and that was a big force that drove the votes in Florida.”31Adelys Ferro, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 18, 2023. On Spanish-language radio in particular, show hosts spread disinformation about immigration into the U.S. and conspiracy theories like the Great Replacement Theory, which falsely claims that non-white immigrants are being deliberately brought into the country to replace white voters for political gain.32“Latinos and A Growing Crisis of Trust,” Equis Institute, 2022, assets.ctfassets.net/ms6ec8hcu35u/1LzjHzFbzNk7a18ojYB6am/4cdcd73632313113b9d038af65b10fa6/Equis_Latinos_and_a_Growing_Crisis_of_Trust2022.pdf. See also Joel Rose, “A majority of Americans see an ‘invasion’ at the southern border, NPR poll finds” NPR, August 18, 2022, npr.org/2022/08/18/1117953720/a-majority-of-americans-see-an-invasion-at-the-southern-border-npr-poll-finds; Alan Nunez, “Latino candidates and voters led the red wave of the 2022 midterms in Florida,” Al Día, November 9, 2022, aldianews.com/en/politics/elected-officials/floridas-latino-red-wave Research from multiple sources indicates that disinformation campaigns stoke anti-immigrant sentiments among Latino and Hispanic communities, increasing the likelihood that they support anti-immigrant policies.33“Latinos and A Growing Crisis of Trust,” Equis Institute, 2022, assets.ctfassets.net/ms6ec8hcu35u/1LzjHzFbzNk7a18ojYB6am/4cdcd73632313113b9d038af65b10fa6/Equis_Latinos_and_a_Growing_Crisis_of_Trust2022.pdf. See also Joel Rose, “A majority of Americans see an ‘invasion’ at the southern border, NPR poll finds” NPR, August 18, 2022, npr.org/2022/08/18/1117953720/a-majority-of-americans-see-an-invasion-at-the-southern-border-npr-poll-finds; Alan Nunez, “Latino candidates and voters led the red wave of the 2022 midterms in Florida,” Al Día, November 9, 2022, aldianews.com/en/politics/elected-officials/floridas-latino-red-wave In September of 2022 at PEN America’s “Choosing Community: Toward a Civic and Informed South Florida” event, Cynthia Perez, progressive activist and cofounder of Cubanos Pa’lante, framed these disinformation narratives as a “fear of the other or fear of an ideology.”34Cubanos Pa’lante, cubanospalante.com/

Ferro recalled another recent example of a disinformation narrative that took hold in communities in South Florida: the repeated claims from Spanish-language radio hosts that the IRS was going to hire 87,000 new agents to audit middle- and working-class taxpayers.35Adelys Ferro, interview by Hannah Waltz, over text, April 25, 2023. The claim is misleading at best: it comes from a Treasury report that estimated the IRS could hire 86,852 new employees over the next decade if they received a budget expansion, but only a fraction of those hypothetical new employees would be enforcement agents.36Katie Lobosco, “5 reasons why the Republican claim about 87,000 new IRS agents is an exaggeration,” CNN, January 11, 2023, cnn.com/2023/01/11/politics/republican-irs-funding-87000-agents/index.html The false claim was repeatedly debunked by mainstream news outlets, but nonetheless spread like wildfire across the country. Tamoa Calzadilla, editor in chief of Spanish-language fact-checking site Factchequeado, told PEN America the narrative was tailored toward immigrants’ economic concerns: “It’s a narrative targeted at the middle class, the working class,” Calzadilla said. “The IRS is building an army with 87,000 agents to rob you of your money.”37Tamoa Calzadilla, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 23, 2023.

Ferro added that this narrative about the IRS exploits the same anxieties of diaspora communities who have fled communist countries. Calzadilla’s team concluded that radio personalities promoting this narrative relied on false equivalencies between the dictatorships in Venezuela, Nicaragua, or Cuba and the Biden administration. “This is a Socialist, Communist, controlling regime, same as your [home] country, you know, and the IRS is a weapon of this Socialist government,” Calzadilla recounted. The Miami Herald’s Mic Check project similarly found that Democrats were routinely cast as “los socialistas” or “los comunistas” on Spanish-language radio.38Andres Viglucci, Joey Flechas, and Lesley Cosme Torres, “How partisan angst, conspiracies thrive in Miami’s Spanish-language media echo chamber,” Miami Herald, December 20, 2022, miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/mic-check-miami/article269058552.html

According to Equis Institute report Latinos and a Growing Crisis of Trust, Latino communities in South Florida “are often siloed into an echo chamber—WhatsApp, YouTube, Facebook, radio, and local TV and newspapers—fomented by local players.”39“Latinos and a Growing Crisis of Trust,” Equis Institute, 2022, assets.ctfassets.net/ms6ec8hcu35u/1LzjHzFbzNk7a18ojYB6am/4cdcd73632313113b9d038af65b10fa6/Equis_Latinos_and_a_Growing_Crisis_of_Trust2022.pdf Ferro affirms that because the Spanish-language radio personalities may understand Latino communities’ cultural context, listeners “actually believe everything that they say.” Some listeners, she says, also have little exposure to other sources of information explaining how the American political system or government works, further impairing their ability to spot falsehoods. This information gap can be exploited by bad actors looking to “create confusion and distrust in order to depress voter turnout or influence voters”.40Ibid.

To combat these falsehoods, Ferro and her South Florida–based Venezuelan American community have been outspoken about the dangerous swirl of mis/disinformation on Spanish-language radio.41Lautaro Grinspan, “Accused of socialism and communism, Venezuelan-Americans say supporting Biden carries stigma,” Miami Herald, September 30, 2020, miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article246056005.html Most recently, in the 2022 midterm election season, she led social media campaigns, hosted events, and gave media interviews calling out disinformation in Spanish-language media.42Venezuelan American Caucus, Instagram, instagram.com/venezuelanamericancaucus; Andres Viglucci, David Smiley, Lautaro Grinspan, and Antonio Maria Delgado, “‘People believe it.’ Republicans’ drumbeat of socialism helped win voters in Miami,” Miami Herald, November 8, 2020, miamiherald.com/news/politics-government/article247001412.html/

Calzadilla and her team at Factchequeado, a fact checking program addressing disinformation in Spanish-speaking communities in the U.S., address disinformation narratives by forcefully debunking them in their own coverage. For example, Factchequeado’s coverage of the IRS “87,000 agents” narrative offers fact-checking and context in Spanish, in addition to an in-depth description of the narrative’s origins and factual inaccuracies.43Rafael Olavarría, “Necesita contexto la frase de Kevin McCarthy sobre eliminar el ‘financiamiento de los 87,000 nuevos agentes del IRS’: es una estimación a 10 años de contratación de personal y no todos serán agentes,” Factchequeado, January 13, 2023, factchequeado.com/verificaciones/20230113/kevin-mccarthy-irs-agentes/ Their online coverage also includes a brief three-sentence header summarizing their findings about a claim. Factchequeado supplies this type of breakdown for each narrative it fact-checks.44Rafael Olavarría, “Sí, el IRS compró $700,000 en municiones en 2022, pero la inversión no es nueva ni inusual,” Factchequeado, September 8, 2022, factchequeado.com/verificaciones/20220809/irs-compra-municiones-2022-contexto/ The organization has developed an alliance of 45 media and institutional partners in 17 states plus Puerto Rico, allowing them to republish their content free of charge, and offers a WhatsApp chatbot where users can report disinformation narratives that they encounter. During the 2022 midterm elections, Factchequeado and partners offered real-time fact-checks on election night and a six-hour live stream countering electoral mis/disinformation targeting Latinos.45“Vive la noche de las elecciones en español con Factchequeado,” November 8, 2022, factchequeado.com/midterms22/20221108/noche-elecciones-espanol-factchequeado/ Their expansive network and reach enable them to stay on top of evolving disinformation narratives across the country.

Pictured from left to right: Ken Molestina, Jean Marie Brown, Miranda Suarez, Jacob Sanchez. Photo by David Moreno

Texas

From PEN America’s research and engagements in the Dallas and Fort Worth areas, several themes emerged regarding how communities are experiencing the effects of and building resilience against disinformation. Our partners emphasized the foundational roles that faith-based communities and centers of worship play in the social infrastructure of Texas, including roles in disseminating information—and sometimes disinformation—and influencing community attitudes toward civic engagement and politics. We heard about voter apathy and low turnout and its intersection with disinformation and faith communities. Local journalists in Fort Worth insisted that understanding “the religiosity of the area is critical” to understanding the flow of information and news. We also heard about how newsrooms are struggling with the impacts of mis/disinformation on their reporting, but also how some are making strides to get out ahead of disinformation and confusion surrounding elections via community engagement journalism.

Natalia Contreras—a Texas-based reporter for Votebeat, an election-focused nonprofit newsroom—highlighted how faith communities and claims related to faith can play a role in the spread of disinformation, and why local journalists who know their communities are essential to combating disinformation in Texas. She shared her experience reporting on election activists challenging the validity of the 2020 election results in Tarrant County.46Natalie Contreras, “Tarrant County conservatives push questions about Texas election integrity,” Votebeat and the Texas Tribune, August 4, 2022, texastribune.org/2022/08/04/texas-election-integrity-tarrant/ The activists claimed that they sought God’s guidance “regarding suspicious election statistics following the November 2020 elections,” and came to the conclusion that voting processes in Texas were flawed.47Ibid. However, they failed to offer evidence of widespread election fraud. Contreras noted that in Texas, decisions about the election process are made at the county level, where local journalists play pivotal roles in breaking down the nuance of these processes: “We are the local reporters; we are the ones watching the county commissioner court meetings when they are approving that funding every year.”48Celebrating the Power of Community Journalism in Fort Worth During Election Seasons,” PEN America, event on October 11, 2022, pen.org/event/celebrating-the-power-of-community-journalism-in-fort-worth-during-election-seasons/ In her reporting about the election activists in Tarrant County, Contreras did exactly that, reporting on county-level meetings where the activists raised their concerns and election workers had space to respond.

Key Partners

PEN America’s key partners in Texas include:

- Dallas Public Library

- All Things Edunia, an educational consultancy run by Martina Van Norden

- Black Voters Matter & the Potter’s House Church

- Fort Worth Report, a nonprofit news outlet serving Fort Worth and Tarrant County

Beyond these organizations, PEN America developed partnerships with individuals throughout the Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan area, including local organizers, community media specialists, journalists, librarians, and faith leaders.

In Dallas–Fort Worth, partners have also routinely highlighted the links between disinformation and voter apathy at the local level. Evidence strongly suggests that election disinformation causes prospective voters to question the integrity of official voting procedures, thus discouraging them from participating at all.49Sergio Martínez-Beltrán, “How disinformation is threatening the midterm elections in Texas,” The Texas Newsroom, October 24, 2022, kut.org/politics/2022-10-24/how-disinformation-is-threatening-the-midterm-elections-in-texas To illustrate, Martina Van Norden, a licensed minister, educator, and organizer based in Fort Worth, pointed to the 2022 midterm elections in Tarrant County, which saw a lower voter turnout than pandemic-era elections. Despite efforts by local organizers to mobilize voters, Van Norden said, “It still wasn’t enough. We still have far too many people who are not voting due to apathy and disinformation . . . It is part of the voter suppression. So, it’s working, unfortunately.”50Martina Van Norden, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 25 and 26, 2023.

I worry just even me writing with my byline and slapping KERA on it is legitimizing it and bringing it into the realm of public conversation.

Miranda Suarez

The racist and anti-Semitic “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory again emerged as a major disinformation narrative. This narrative has taken root in some conservative circles in Texas, and has been espoused by some elected officials.51Robert Downen, “How Texans helped plot, foment and carry out the Jan. 6 insurrection,” Texas Tribune, January 6, 2023, texastribune.org/2023/01/06/texans-jan-6-insurrection/; William Melhado, “Gov. Greg Abbott embraces ‘invasion’ language about border, evoking memories of El Paso massacre,” Texas Tribune, November 18, 2022, texastribune.org/2022/11/18/texas-greg-abbott-immigration-invasion-el-paso/ The increased dissemination of disinformation by candidates and elected officials may be having an ancillary impact on journalism. Some of the local journalists in Fort Worth who spoke to PEN America and wished to remain anonymous said that they were increasingly being stonewalled by politicians who refuse to speak with journalists, saying they “did not share the same definition of disinformation” as the journalists. Journalists also reported having trouble communicating with school boards and law enforcement. Before engaging with these officials, the journalists would first have to work to undo preconceived notions about journalists: “[To them], we’re either completely irrelevant or the reason of all evil,” said one journalist. Said another, “They don’t trust us.”

That lack of trust and dialogue between elected officials and the journalists reporting on them can have cascading impacts. During a town hall conversation with other local journalists in Fort Worth, Miranda Suarez, Tarrant County accountability reporter at KERA, Dallas–Fort Worth’s NPR-affiliate radio station, said that sometimes she struggles deciding whether or not to cover election-related disinformation spreading in the area.52Celebrating the Power of Community Journalism in Fort Worth During Election Seasons,” PEN America, event on October 11, 2022, pen.org/event/celebrating-the-power-of-community-journalism-in-fort-worth-during-election-seasons/ “Am I just amplifying it? What is a responsible way to debunk it?” She said that even when she does call it out as false information, “I worry just even me writing with my byline and slapping KERA on it is legitimizing it and bringing it into the realm of public conversation.”

Finding Community: The Role of Faith Leaders

Part of building strong communities is sharing information that fosters growth, belonging, and togetherness; mis- and disinformation break down the bonds of neighbors and chip away the civility of those in the community.

Martina Van Norden

Speakers at a Potter’s House Church event in April 2023 pose for a photo: Sanderia Faye, Martina Van Norden, Dr. James Whitfield, Jamie Jackson (left to right). Photo by Hannah Waltz

Most of the Texas-based journalists and faith leaders with whom PEN America spoke were quick to point to the role of people’s faith communities in daily life, including their politics. They stressed that faith communities play a particularly influential role during election season in Texas; faith leaders often espouse political information and, in some cases, even risk breaking federal law that bars them from endorsing candidates.53Jeremy Schwartz and Jessica Priest, “Churches are breaking the law and endorsing in elections, experts say. The IRS looks the other way,” Texas Tribune, October 30, 2022, texastribune.org/2022/10/30/johnson-amendment-elections-irs/ As one journalist described it, “churches are at the center of everything.”54Conversation with local journalists in Fort Worth, PEN America, in-person conversation in August 2022.

Minister and organizer Martina Van Norden told PEN America that when it comes to disinformation, “the Church has to be a part of [the solution].” Van Norden expressed concern that congregants aren’t receiving the context necessary to understand the complexity of divisive political—or politicized—topics in Texas when they exclusively get their information about these topics from faith leaders.

In her own ministry, Van Norden regularly engages members in conversations around civics and democracy. She is also currently hosting and producing a series of civic engagement–oriented discussions with the Potter’s House, a nondenominational, multicultural church in Dallas with more than 30,000 members recognized as one of the most influential churches in the country.55Elisha Fieldstadt, “America’s Biggest Megachurches, Ranked,” CBS News, November 26, 2018, cbsnews.com/pictures/30-biggest-american-megachurches-ranked/6/ To develop the series, Van Norden engaged PEN America and other democracy organizations like Black Voters Matter, as well as journalists from the Dallas Morning News and other outlets. “We know a free press is very much a part of democracy. If you don’t have the freedom of speech and a free press, you lose those mechanisms to ensure a democracy,” Van Norden explained.

The series, which Van Norden has dubbed “Ministry in Civics,” hosted its first event at the Potter’s House in March 2023. The event, a disinformation-defense–oriented panel program entitled “Fake News” or Not?, exemplified the importance of breaking down silos between sectors to more fully understand the spread of disinformation and develop cross-disciplinary strategies for addressing it.56“‘Fake News’ or Not?” PEN America and the Potter’s House, event on March 25, 2023, pen.org/event/panel-discussion-at-the-potters-house-of-dallas-fake-news-or-not/ The gathering began with a brief lesson on how Texas legislative sessions function, then transitioned into an informal panel discussion between journalists, voting rights experts, and attendees, after which all parties mingled to converse. Journalists like Eva Coleman of the Texas Metro News and Deputy Publisher of the Dallas Morning News Leona Allen, who spoke on the panel, discussed the importance of examining where voters—and journalists—are getting their information.57Eva D. Coleman, “My MIC Sounds Nice, Check One!” Texas Metro News, March 27, 2023, texasmetronews.com/52613/my-mic-sounds-nice-check-one/ Coleman and Allen emphasized the importance of voters being equipped to identify credible sources for information about elections and candidates, and the related responsibility of journalists to consult with individuals in the community. During the event, Allen, for example, explained how the Dallas Morning News produces their candidate questionnaires and other voter guides, which serve to demystify reporting on local election cycles.58Voter Guide, The Dallas Morning News, dallasnews.com/voter-guide/2023-spring/

Panelists at a Potter’s House Church event in March 2023: Eva D. Coleman, Jazmyn Ferguson, Martina Van Norden, Leona Allen, Denita Jones (left to right). Photo by Hannah Waltz

Van Norden, who moderated the series, emphasized the potential ripple effect that these types of discussions can have in faith communities by providing the faith leaders in attendance with the tools to share accurate information—about elections, education, and more—with their ministries: “Part of building strong communities is sharing information that fosters growth, belonging and togetherness, but mis- and disinformation break down the bonds of neighbors and chip away the civility of those in the community,” Van Norden said. “Our strategy for change is to touch 10 [people] with the truth. As we continue our work to increase civic engagement, we prioritize creating opportunities to share reliable and credible information with our families and neighbors.”

In addition to the Potter’s House series, a number of other national multifaith organizations have also turned their attention to Texas, with a special focus on “interrupting pathways to radicalization,” and disrupting the flow of disinformation. Attendees of PEN America’s pre-election strategy session with Texas community leaders told us that faith leaders often don’t feel equipped to call out disinformation or extreme rhetoric that goes viral online and manifests in real-world violence. Moreover, they don’t know how to “bring down the temperature” when heated conversations arise in religious spaces. John Thielepape, director of projects at the Multi-Faith Neighbors Network based in the Dallas–Fort Worth region, has been experimenting with language and framing in his conversations with faith leaders in Texas, and he asks his network of leaders, which he calls a “resilience team,” to “lovingly confront disinformation.”59Multi-Faith Neighbors Network, mfnn.org/ As he told PEN America, “[t]he resilience team is focused on creating initiatives that increase unity and peacemaking in the community, and shrinking the space for division.60John Thielepape, in-person conversation with PEN America, October 11, 2022. This is formed out of people who express interest in doing the work of unity and peacemaking. “We work with the team to find out where the points of division are in the community and try to plan ways to confront and redirect that activity.”

Texting in Texas: Demystifying Elections by Listening to the Community

As part of their effort to combat disinformation and address voter needs during the 2022 midterms, the Texas Tribune, a nonprofit news website, reoriented a program by which readers can sign up to receive information by text message—initially launched to share updates and answer questions during Texas’s winter storm and associated power outages in 2021—to explicitly offer factual information about the process of elections and voting.61Texas Tribune, Texting Line, joinsubtext.com/texastribune; Bobby Blanchard, “You can now text with The Texas Tribune for breaking news, power updates and more,” Texas Tribune, February 18, 2021, texastribune.org/2021/02/18/texas-tribune-text-phone-number-news-updates/

María Méndez, service and engagement reporter at the Texas Tribune, was a part of that shift. Méndez, speaking to PEN America, said, “Community engagement and service journalism means getting to know the information needs of your audience, and what additional context or help they need to understand some of these really big political issues that come up in the news consistently.”62María Méndez, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 20, 2023.

It’s easy to sometimes chalk up misinformation to bad actors that are just doing it for the sake of doing it, as opposed to realizing that people might just have an issue or a misunderstanding, and they want to help but maybe they don’t have the full context, or the full story, or don’t know how to exactly go about helping others in a way that doesn’t lead to rumors or misinformation.

María Méndez

Méndez gave an example of how this works: in October 2022, she published a story detailing misconceptions about how voting machines were working.63María Méndez, “No, Texas voting machines aren’t switching your votes,” Texas Tribune, October 28, 2022, texastribune.org/2022/10/28/texas-voting-machines/ After the story was published, Méndez followed up with one voter who had shared her misconceptions. “She thanked us,” Méndez recalled, “and raised concerns like, ‘why aren’t voting machines more user-friendly?’” The takeaway for Méndez was that “we shouldn’t just be chalking voter skepticism about the accuracy of voting machines up to user error.” This is especially dangerous because official announcements pointing exclusively to user error risk alienating those who experience difficulties throughout the voting process, Méndez said, potentially making them more open to disinformation narratives claiming the election is being rigged.

Méndez’s approach at the Tribune has been to consider the information needs of “everyday Texans,” people who are less engaged in politics but still want to participate. “We did a callout asking people what they wanted to learn about elections and the electoral process, and something that came up a lot was voter requirements,” as well as the ballot-counting process. Méndez’s team took those questions as a directive to write a feature story on the counting process, noting that it’s important to take advantage of moments when readers are especially curious.64María Méndez, “How Texas counts ballots and keeps elections secure,” Texas Tribune, November 4, 2022, texastribune.org/2022/11/04/texas-ballot-counting-secure-elections/ “I think people are hungry for that type of information.”

The texting line and election explainers have been met with positive reception from users, as well as state and local officials who, Méndez said, praised the election stories for increasing broad-based civic literacy and engagement. The team is actively looking for ways to better tailor the line to voters’ needs and solicited feedback from members on areas for expansion after the 2022 elections. Member responses ranged from simple requests for information on tracking bills to broader guidance on how to get more actively involved in the state legislature and local government.

For Méndez, community-oriented journalism helps complicate simplistic narratives around misinformation: “It’s easy to sometimes chalk up misinformation to bad actors that are just doing it for the sake of doing it, as opposed to realizing that people might just have an issue or a misunderstanding, and they want to help but maybe they don’t have the full context, or the full story, or don’t know how to exactly go about helping others in a way that doesn’t lead to rumors or misinformation.” And in a state that has lost more newspaper journalists per capita than all but two others, getting journalists out in the community to engage with their readers is more important than ever.65Sewell Chan, “Since 2005, Texas has lost more newspaper journalists per capita than all but two other states,” Texas Tribune, June 29, 2022, texastribune.org/2022/06/29/death-local-news-texas/

Arizona

Arizona has been at the center of multiple disinformation narratives that have sown doubt in the electoral process.66Miles Parks, “Experts Call It A ‘Clown Show’ But Arizona ‘Audit’ Is A Disinformation Blueprint,” NPR, June 3, 2021, npr.org/2021/06/03/1000954549/experts-call-it-a-clown-show-but-arizona-audit-is-a-disinformation-blueprint; David Klepper, “Post-election misinformation targets Arizona, Pennsylvania,” Associated Press, November 10, 2022, apnews.com/article/2022-midterm-elections-misinformation-nov-10-70af6e17061753a87e79df67825d619f Following the 2020 presidential elections, a politicized audit process—initiated by Arizona Senate Republicans—sought to prove there was election fraud in Maricopa County. The review, which one former Department of Homeland Security official described as “an audit in name only” and was widely dismissed as a political stunt, actually confirmed that Biden had won the state, but identified many supposed irregularities.67Ibid. A year later, in January of 2022, Maricopa county officials issued a formal, 93-page rebuttal of the audit results, rebutting every one of the 75 claims of irregularities that the audit team had made; the company, Cyber Ninjas, that conducted the audit, shut down shortly thereafter.68Jeremy Duda, “Maricopa County rebuts ‘audit’ findings, GOP’s bogus election claims,” AZ Mirror, January 5, 2022, azmirror.com/2022/01/05/maricopa-county-rebuts-audit-findings-bogus-election-claims/; Michael Wines, “Cyber Ninjas, Derided for Arizona Vote Review, Says it is Shutting Down,” The New York Times, January 7, 2022, nytimes.com/2022/01/07/us/cyber-ninjas-arizona-vote-review.html Still, the audit, conducted at the behest of elected officials, sowed public doubt in the validity of the electoral process.69“Continuing Coverage: The Arizona election audit,” KJZZ, kjzz.org/arizona-election-audit-coverage Conducted over months rather than the weeks originally estimated, the audit dominated Arizona news cycles, cast doubt on election administration in the state, and laid the ground for even more disinformation to take hold.70Michael Wines, “Arizona’s Criticized Election Review Nears End, but Copycats Are Just Getting Started,” The New York Times, September 23, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/09/23/us/arizona-election-review.html; Maricopa County Elections, “Just the Facts,” last accessed May 22, 2023, elections.maricopa.gov/voting/just-the-facts.html#CorrectingtheRecord; Reid Wilson, “Five takeaways from Arizona’s audit results,” The Hill, September 24, 2021, thehill.com/homenews/campaign/573888-five-takeaways-from-the-arizonas-audit-results/; Dan Balz, “Arizona audit debunks Trump’s false claims, but the poison of misinformation still threatens the electoral process,” The Washington Post, September 25, 2021, washingtonpost.com/politics/dan-balz-take-arizona-review/2021/09/25/d95f8ccc-1da8-11ec-a99a-5fea2b2da34b_story.html.

Key Partners

PEN America’s key partners in Arizona include:

- The News Co/Lab based at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University

- InSite Consultants and the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) Phoenix

- News outlets: Conecta Arizona and Votebeat

Collette Blakeney Watson leads a discussion at a gathering in March 2023, while Hannah Waltz and William Johnson look on. Photo by Mary Stephens

Another disinformation narrative with lasting effects known as #SharpieGate originated during the 2020 presidential election cycle in Arizona and continued to erode voter trust in the 2022 midterms in Arizona.71Tina Nguyen and Mark Scott, “How ‘SharpieGate’ went from online chatter to Trumpworld strategy in Arizona,” Politico, November 5, 2020, politico.com/news/2020/11/05/sharpie-ballots-trump-strategy-arizona-434372 Jen Fifield, a Phoenix-based reporter for Votebeat, a nonpartisan newsroom that offers local reporting on elections and voting, has been covering “Sharpiegate” since 2020. As many disinformation campaigns do, Sharpiegate was born from valid and benign misunderstandings; in this case, voter confusion and poor messaging about the new use of Sharpie pens for voting in Arizona in 2020, after years of voters being told not to use them. The false narrative emerged that using Sharpies to cast votes would cause a bleed on the ballots, invalidating them, and that election officials were giving Sharpies to Republicans in order to invalidate their votes.72Jessica Huseman, “How election lies led to real problems in Maricopa County,” Votebeat, April 17, 2023, votebeat.org/2023/4/17/23682372/sharpiegate-maricopa-county-election-conspiracies; Jen Fifield, “Could Arizona election officials have done more to prevent ‘Sharpiegate’ this election?,” Arizona Republic, November 11, 2020, azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2020/11/11/sharpiegate-could-arizona-election-officials-have-prevented-it/6229217002/ By the time the 2022 midterm elections arrived two years later, voters were distrustful of the county’s recommendation to use Sharpie to fill in ballots, a recommendation that came straight from the company that made the voting machines (Dominion Voting Systems).73Jen Fifield, “Too big of a job: Why Maricopa County’s ballot printers failed on Election Day,” AZ Mirror and Votebeat, December 9, 2022, azmirror.com/2022/12/09/too-big-of-a-job-why-maricopa-countys-ballot-printers-failed-on-election-day/ Capitalizing on this suspicion and confusion, “Republicans had been telling voters to bring their own pens to voting locations because they didn’t trust the pens here,” said Fifield.74Jen Fifield, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, February 1, 2023. The claim about the Sharpies, despite being repeatedly debunked, contributed to the county’s decision to print ballots on thicker paper, which resulted in clogged voting machines in Maricopa County in November of 2022, leading to exacerbated voter confusion and suspicion, and further depleting trust in the state’s election mechanisms.

Despite the prominence of these cases, our partners working on the ground in Phoenix told PEN America that any version that casts Arizona as a place where disinformation rules the narrative misses much of the character of the state’s journalistic and political culture. “I think a lot of times people hear Arizona and they think that it’s this Wild West atmosphere where no one trusts the government,” said Fifield, who was born and raised in Phoenix. But she stressed that that national narrative misses the mark: “We have an excellent media landscape here, and one thing . . . in my role covering just elections I have noticed that there is a lot of election coverage and a lot of fact-checking that happens in the media regarding election misinformation. There’s a concerted effort with TV, radio, and traditional media to really serve voters and inform them.”75Jen Fifield, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, February 1, 2023.

Jared Davidson of Protect Democracy concurred with this assessment: “It takes a village in Arizona,” he told PEN America. He noted that following the 2020 election, “[w]e had a secretary of state who is not an election denier, and who . . . really leaned into combating misinformation and working with community organizations and those on the ground to combat misinformation. The Board of Supervisors and the county recorder [in Maricopa County], almost all of whom are Republican, were all leaders in countering disinformation.”76Jared Davidson, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 27, 2023.

At the same time, we also heard from partners that high-quality journalism is not always readily available to everyone in Arizona. In our conversations with community media journalists and organizers, PEN America heard that Arizonans are concerned about the digital access gap in low-wealth communities and communities of color, as well as the accessibility of in-language journalism for non-English speakers. “Equitable access also means equity in the quality of that news and information,” Collette Blakeney Watson of Media 2070 said at a March 2023 gathering in Phoenix.

PEN America’s partners in Arizona emphasize the central role of the state’s growing racial and ethnic diversity in its political and media landscape, and note that legacy news media has largely failed to keep up with these changing demographics. In 2022, Arizona boasted the highest percentage of inbound moves in the country, and it is home to the third fastest-growing Black population in the country.77Alejandra, O’Connell-Domenech, “Arizona most popular state to move to in 2022,” The Hill, February 2, 2023, thehill.com/changing-america/sustainability/infrastructure/3841874-arizona-most-popular-state-to-move-to-in-2022/; Adam Mahoney, “For Black families, it isn’t simple creating roots in Phoenix,” High Country News, February 6, 2023, hcn.org/issues/55.3/south-communities-for-black-families-it-isnt-simple-creating-roots-in-phoenix Yet there is still only one newspaper in the state specifically serving the Black community.78Arizona Informant, azinformant.com/, Robrt L. Pela, “Fifty Years on, the Arizona Informant Is Still Covering the Black Community,” Phoenix New Times, July 30, 2021, phoenixnewtimes.com/news/the-arizona-informant-cloves-campbell-jr-11694238 Additionally, indigenous and Black Arizonans are historically and presently more likely to live in areas with fewer local newspapers.79Ruxandra Guidi, “Across the West, news deserts spread: But civic engagement is taking other forms,” High Country News, September 14, 2022, hcn.org/articles/media-across-the-west-news-deserts-spread

Native American voters in Arizona are increasingly recognized as holding the power to decide elections, making them potential targets for voter suppression and disinformation, a point also made by Mark Trahant, editor-at-large of the public-service nonprofit newsroom ICT (formerly Indian Country Today) in conversation with PEN America.80Shondiin Silversmith, “Native voters could swing close races if turnout is high, advocates say,” AZ Mirror, November 7, 2022, azmirror.com/2022/11/07/native-voters-could-swing-close-races-if-turnout-is-high-advocates-say/; Sue Halpern, “the Political Attack on the Native American Vote,” The New Yorker, November 4, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-political-attack-on-the-native-american-vote; Mark Trahant, in-person conversation, August 10, 2022. Diné journalist Shondiin Silversmith, who is based on the Navajo Nation and serves as the Indigenous Communities Reporter for the Arizona Mirror, emphasized to PEN America that keeping disinformation at bay about and within indigenous communities requires acute attention to how these communities are covered, and ensuring they are covered by reporters who understand them and have their trust. “When you don’t have a basic understanding of how tribal nations operate, that’s when the door is open to disinfo,” Silversmith said. “So when large events happen that impact everyone across the country, you have people popping up that try to relate it to tribal communities and might get the information wrong, but when you have ICT and other indigenous reporters, you combat that.”81Shondiin Silversmith, phone conversation, June 20, 2023.

Running a Debunking Service on WhatsApp

Many of PEN America’s partners in Arizona are focused on identifying and combating disinformation among the state’s Spanish-speaking communities. Many recent studies have found glaring gaps in Spanish-language media coverage in the U.S. In 2022, for example, a team of researchers at the University of Houston found that Spanish-language resources on COVID-19 in cities like Phoenix were “inferior or nonexistent” compared to their English counterparts.82Kusters, I.S., Gutierrez, A.M., Dean, J.M. et al. Spanish-Language Communication of COVID-19 Information Across US Local Health Department Websites. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2022). doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01428-x And the Center for Community Media’s Latino Media Initiative reported in 2020 that “coverage by Spanish-language media of the three issues that matter most to Latinos in the United States (immigration, health care, and employment) has been falling since the beginning of the Trump administration,” while social media platforms like Facebook consistently issue warning labels on Spanish-language disinformation far less frequently than disinformation in English. Lacking adequate in-language resources about matters they care about, many Spanish speakers turn to social media.83“The News Agenda of Latino Media in the U.S.,” Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, City University of New York, 2020, latinomediacontent.journalism.cuny.edu/en/introduction/; “How Facebook can Flatten the Curve of the Coronavirus Infodemic,” Avaaz, April 15, 2020, secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/facebook_coronavirus_misinformation/ In the words of Maritza Félix, one of PEN America’s partners in Arizona, “It’s not that Spanish speakers are more vulnerable to misinformation . . . the thing is that we don’t have access to the same quality information that everybody else has.”84Maritza Félix, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 24, 2023.

Félix’s organization, Conecta Arizona, was created in May 2020 to fill gaps in information for Spanish speakers regarding COVID-19.85Conecta Arizona, conectaarizona.com/; Maritza Félix, “Conecta Arizona: How a WhatsApp group redefined journalism on the border,” NBCU Academy, July 8, 2021, nbcuacademy.com/maritza-felix-conecta-arizona-whatsapp-group-journalism-border/ But after spending the first half of 2020 addressing COVID-19 misinformation, Félix pivoted during the presidential election season to answer hundreds of questions about voting procedures and requirements in the United States. Conecta Arizona targeted a particularly underserved constituency: dual citizens going back and forth across the border who would be voting for the first time in the United States.

Conecta Arizona uses a WhatsApp group with more than 1,000 members as its key medium for disseminating news and information. Spanish-speaking immigrants in Arizona have flocked to the app in recent years, using it to communicate with family and friends on both sides of the border.86Martin J. Riedl, Joao Vicente Seno Ozawa, and Samuel C. Woolley, “Talking Politics on WhatsApp: a Survey of Cuban, Indian, and Mexican American Diaspora Communities in the United States,” November 2, 2022, mediaengagement.org/research/whatsapp-politics-cuban-indian-mexican-american-communities-in-the-united-states/ For Félix, pursuing a WhatsApp-first communication strategy was a way of reaching Arizonans—and those across the border in the Mexican state of Sonora—where they’re already receiving their information. “The heart of Conecta Arizona beats on WhatsApp,” she explained. For Mexican American communities, “We communicate with our families through WhatsApp. We share good news and bad news through WhatsApp, we send audio messages, we send text messages. And we [unintentionally] send misinformation on WhatsApp too. We try to combat disinformation and misinformation using the same channel [where] it’s getting spread.”

Conecta Arizona hosts original programming on WhatsApp, such as its “La Hora del Cafecito,” or “coffee hour,” held over 850 times since its launch in 2020, in which Félix and invited experts answer member questions. In recent months, they have also created a radio show and podcast, a Telegram channel, and a Substack newsletter, with the intention of providing multiple media for sharing reliable information in Spanish.87Cruzando Líneas podcast, cruzandolineas.com/

In 2022, Conecta Arizona developed a series of 13 midterm election guides addressing the topics of top concern to its WhatsApp group members.88Guias, Conecta Arizona, conectaarizona.com/tag/g/ Félix was quick to note that, while safety at the border is one of the top priorities for Latino communities in Arizona, it isn’t their only concern. “Their concerns are not just immigration . . . it’s about inflation, education, and everything that we have going on.” Félix told PEN America that very few candidates “actually took the time to engage with the Latino community in Spanish, and if they did it, they did it the last week” of the race. Conecta Arizona sought to fill this gap by outlining for its members the policies and positions of candidates for national and statewide office, including the candidates’ proposals on immigration, the environment, education, and the economy, and how those policies would affect Latino communities in Arizona. The guides also documented the extent to which candidates were reaching out to Latino communities.

Community media outlets like Conecta Arizona can offer a promising, evidence-based antidote to disinformation targeting communities that may feel disconnected from mainstream news sources. In March 2023, the Columbia Journalism Review released a report examining whether the fact-checking activities conducted by Conecta Arizona and other similar outlets improved factual accuracy among readers.89Yamil R. Velez, “Community-Centered Outlets Empower and Inform Latinos,” Columbia Journalism Review, March 22, 2023, cjr.org/tow_center/community-centered-outlets-empower-and-inform-latinos.php The research team found that these outlets’ disinformation interventions had a profound impact, “deliver[ing] accurate information and also enabl[ing] Latinos to engage actively in the political process.” Readers of Conecta Arizona and similar outlets reported feeling more qualified to participate in politics, said that they were more likely to vote, and were aware of both local and national issues. The study suggests that expanding on the model of Conecta Arizona has tremendous potential for building disinformation resilience in Spanish-language communities.

Organizations like Conecta Arizona have the potential to get out ahead of false information by “proactively engaging communities in Spanish, informing them, answering the questions before, with a lot of time for them to read, to talk about, to ask questions, to participate and engage in civics in Arizona.”90Maritza Félix, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, January 24, 2023. And such deeply embedded organizations are well-positioned to distill information about national and statewide elections so as to effectively inform and empower their communities.

Priorities for Community Disinformation Resilience

PEN America’s work with community leaders in Florida, Texas, and Arizona highlights how disinformation can exploit cracks in the information environment left by the decline of local news, increasing political polarization, and gaps in cross-cultural fluency. PEN America has identified the following priorities for efforts to build community resilience to disinformation during the upcoming 2024 election season. To the extent that these findings are useful to other stakeholders, we strongly support continued experimentation and iteration of these efforts and welcome feedback as new information and observations develop.

Breaking Down Silos

PEN America’s conversations and engagements with individuals and organizations in Texas, Florida, and Arizona over the past year have highlighted the value of communicating and connecting across communities, disciplines, and differences to identify and get ahead of disinformation and foster healthier information environments.

For example, the week before the midterm elections, PEN America convened local journalists, community organizers, academic researchers, librarians, and faith leaders in Texas to discuss messaging strategies to get out ahead of election disinformation narratives. The virtual gathering was an opportunity to exchange ideas across disciplines and regions in Texas for a more connected and consistent line of messaging to the communities they serve. Several of our interviewees in Texas who attended the session reflected on the approach. “One thing that I found interesting . . . was bringing together community groups and leaders with journalists,” María Méndez of the Texas Tribune noted. “I think that can be helpful.”

Through their own research at the University of Texas, Kayo Mimizuka observed that people in Texas who participated in their study on how the spread of mis/disinformation on encrypted messaging apps affects diaspora communities wanted to be able to connect with journalists: “They have no access to journalists who are working to confront mis/disinformation, particularly for diaspora communities.”91Kayo Mimizuka, interview by Hannah Waltz, over Zoom, February 3, 2023; Inga Kristina Trauthig and Kayo Mimizuka, “WhatsApp, Misinformation, and Latino Political Discourse in the U.S.,” Tech Policy Press, October 25, 2022, techpolicy.press/whatsapp-misinformation-and-latino-political-discourse-in-the-u-s/ Tamoa Calzadilla, of Spanish-language fact-checking site Factchequeado, agrees that making these connections is important. “We have to improve our skills to build a big alliance and invite a lot of people with different approaches to Spanish-speaking audiences,” Calzadilla told PEN America. “And I absolutely believe in the power of collaboration with different approaches and different words sometimes.” As Calzadilla points out, something as simple as using different words to discuss disinformation—without using the often-fraught term “disinformation”—to express the same idea can break down communication barriers and create space for open dialogue.