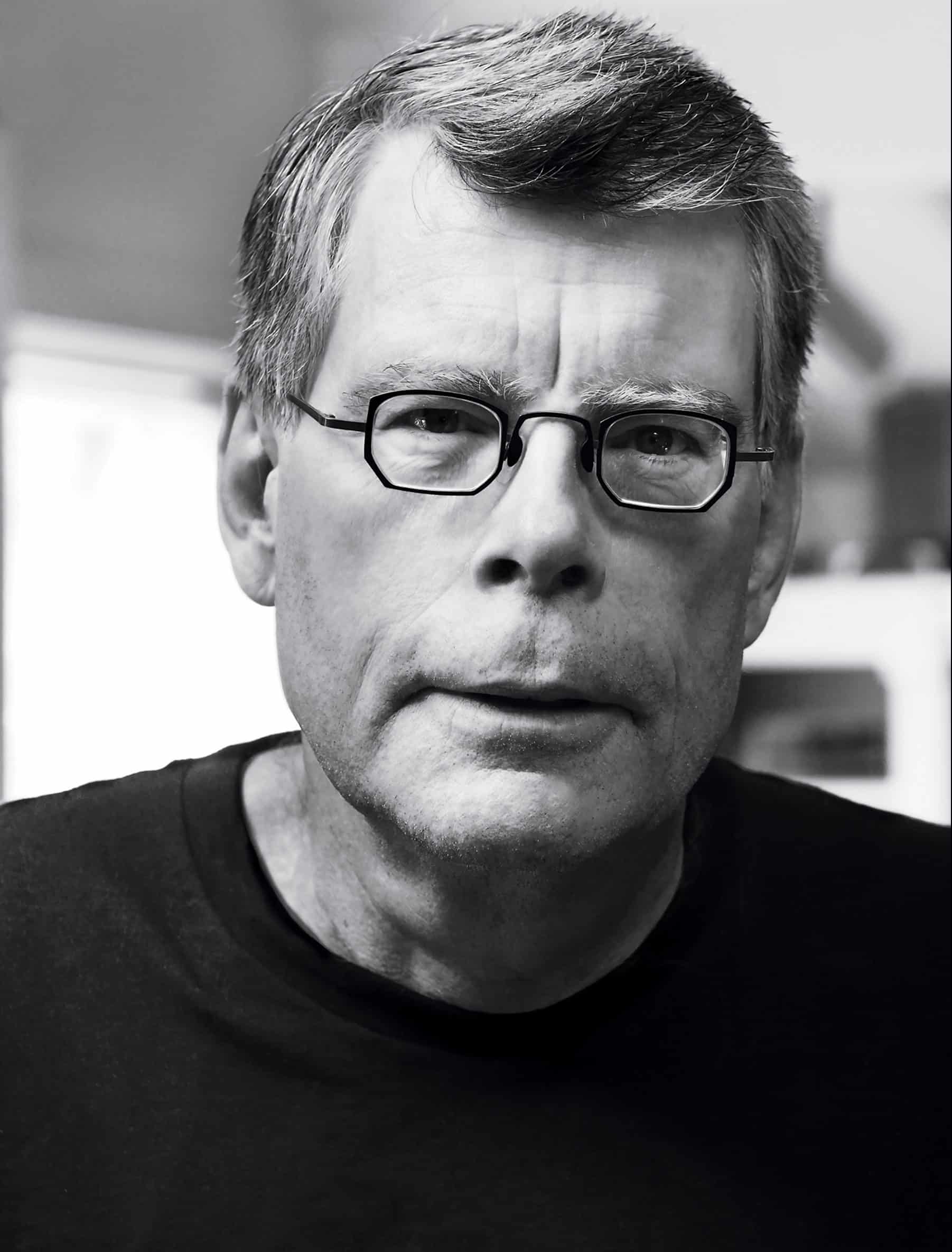

Stephen King is the author of more than 50 books, all of them worldwide best sellers and many—including such classics as It, The Stand, The Dark Tower, Misery, Lisey’s Story, 11/22/63, On Writing, Under the Dome, and many more—providing the basis for major motion pictures and serving as cultural hallmarks for generations. Among his many accolades are the 2003 National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters and the 2014 National Medal of Arts presented by Barack Obama. His depictions of horror and violence have also earned him a title as one of the most banned or challenged authors in recent decades. King is an impassioned advocate of freedom of expression, literacy, and access to information, which he and his wife Tabitha support through their philanthropy. King’s Haven Foundation also provides unique and generous support to writers and other freelancers in the arts who have suffered personal hardship. His outspoken defense against encroachments on free speech and pointed public criticism of policies that infringe on this and other rights have resulted in his being blocked by President Trump on Twitter.

Below are his full remarks from the 2018 PEN America Literary Gala, including an introduction by the actor Morgan Freeman.

Morgan Freeman

Thank you very much. My friend Stephen King is a dauntless champion of the written word. Stephen’s body of work—over 60 novels—have riveted, terrified, and inspired generations of readers. They have made long train rides, bedtimes, and rainy afternoons portals into unforgettable new worlds and into the depths of our own fears. But compelling, impossible-to-put down writing and indelible stories are one of the reasons PEN America has chosen to honor Stephen tonight.

Stephen King is the embodiment of three threads at the core of PEN America:

- the writer as humanitarian

- the writer as conduit to bring unseen and unheard human experiences to life

- the writer as activist, using the power of the pen to shape the world

Stephen’s humanitarianism is a fusion of boundless generosity and profound humility. I will mention but one area, close to the heart of the literary community gathered in this room. Nearly 20 years ago Stephen was struck by a car during a daily walk and couldn’t write for a period of about 10 months. Shortly thereafter a close friend of his saw his career as an audio reader ended after a head injury. Jarred by the plight of creative individuals stymied and silenced by injury, Stephen founded the Haven Foundation to assist freelance artists who face personal misfortune. The Haven Foundation is a longstanding supporter of the PEN America Writers Emergency Fund, which assists authors who have fallen on hard times—those who need surgery, or therapy, a prosthetic limb, help with a rent check, or an attorney’s fee for an asylum application. All the assistance is strictly anonymous. This year, thanks to Stephen King’s Haven Foundation, PEN America-supported stricken writers got back to work right after the hurricanes in Puerto Rico.

Through his writing Stephen King is an emissary who brings often remote stories, identities, and experiences into focus. When I first read the script of Shawshank Redemption, inspired by Stephen King’s novella, I said I’ll be willing to play any part. I did, and I would have. Stephen brought compassion and humanity to the forgotten in prison, getting readers and audiences all over the world invested in their future and their freedom. The work touches upon so much of what PEN America stands for—encouraging the incarcerated to tell their own stories through PEN America’s Prison Writing Program and the PEN Prison Writing Awards, the only awards anywhere that recognize the best writing from the inside.

Defending access to books in prison, as PEN America has done in New York State, New Jersey, and across the country through its Right to Read campaign, is a cause embodied in the prison library in Shawshank, a place of refuge, wonder, and spiritual escape. Stephen’s portrayal of the yearning for human freedom in Shawshank was so potent that when a Chinese dissident managed a daring prison break a few years back, one of the first things Beijing authorities did was ban the very word “Shawshank” on social media and internet searches. They knew that Stephen King’s words and story had the force to inspire—a power they were determined to crush.

Finally, hardly least, the writer as activist. It was among PEN America’s darkest hours when Iran’s Supreme Leader declared a fatwa on author Salman Rushdie. With riots and firebombings triggered by a dictator irate at a novel, bookstores were fearful for the safety of their employees and customers, so they began pulling The Satanic Verses from their shelves. Stephen King called up the head of a major chain of stores and gave him an ultimatum: “You don’t sell The Satanic Verses, you don’t sell Stephen King.” Well of course the store reversed course. “You can’t let intimidation stop books,” King said. “It’s as basic as that. Books are life.”

A fierce opponent of censorship, Stephen is outspoken about the dangers of pulling books from the shelves of schools and libraries.

In an age of new assaults on the press and truth, Stephen has taken his public platform and transformed it into a vehicle for unfiltered dissent.

Stephen calls it likes he sees it and has become a clarion voice of unvarnished, sometimes harsh truths. Some people can’t take it. Would rather not hear the truth. When President Donald Trump blocked Stephen King on Twitter, Stephen didn’t cower for a moment. He came right back at the president, declaring him blocked from seeing Stephen King’s next film. Hallelujah. Stephen is a champion and personal exemplar of what PEN America stands for—the freedom to write.

Thank you, Stephen, for your boundless contributions to writers, to readers, and to all of us who believe that “Fear can hold you prisoner, but hope can set you free.”

I am honored, honored to stand here tonight to present the PEN America Literary Service Award to my friend, Stephen King.

Stephen King

That’s the best goddamn introduction I ever had. And probably the best one I’ll ever get. And before I go on, I just have to tell you one little story: You know, my wife and I live half the year in Florida. We turn 65 and it’s the law. So, we have to go there. And my wife does the big shopping. She’s here tonight. She’s my inspiration, Tabitha King. She does the big shopping because she doesn’t trust me to do that, but if we’re out of toilet paper or something, she will send me to the store. And so I was in Publix one day, and I came around the corner of the aisle, and there was a woman coming the other way—you could tell she was a Florida resident because she had the dark, dark sort of shoe leather skin, ya know, and a golf hat. She was wearing one of those rider things. And she looked at me and she said, ‘I know who you are.’ And I said, ‘I know who I am, too.’ She said, ‘You write those scary things. You write those scary books. Like the Pet Cemetery book. And some people like those books. Some people like them, and you could do what you want, but I like uplifting things like that Shawshank Redemption. ‘ And I said, ‘I wrote that.’ And she said, ‘No you didn’t.’

Anyway. It’s a wonderful award, and I want to thank Morgan Freeman and all the honorees tonight. Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo for their bravery and defense of honest journalism. Carolyn Reidy from my publishing company, for her support. And Nan Graham, who’s edited all my books. They reminded me of some of my French 1 themes when she got done with some of those books. She told me not to mention them, but I’m surrounded by good women at Simon & Schuster, who’ve helped me to mind my business. Carolyn Reidy is one. Nan Graham is another. Susan Moldow is here tonight. She’s terrific. Katie Monaghan is here tonight. Roz Lippel. And they’ve all helped to make me a better person, as well as a better writer. And that goes double for my wife. And I especially want to thank the young people from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, for their fierce advocacy and hard work in the wake of yet another horrific school shooting, not even the most recent now. They have stood up admirably to the vituperation of this country’s gun extremists, who seem to feel that the occasional blood sacrifice is acceptable in defense of a Second Amendment that was written at a time when such weapons as the AR-15 and the Bushmaster XM-15 did not exist. So I feel like I’m in excellent company here tonight.

You know, I’m just a guy who’s loved books ever since childhood, when a big green Bookmobile appeared in my little Maine town once or twice a month, bringing adventure, and mystery, horror, amusement, and news of the outside world. I met my wife in a library, and take it from me there is no better basis than books when it comes to a long marriage. We’ve been together almost 50 years, so I can say the binding held.

And listen, I’ve been extremely well-rewarded along the way, and extremely lucky. Somewhere in the neighborhood of 800,000 books are published in America each year, just in America, and very few men and women can earn a living from their work as writers. The percentage of readers is relatively small compared to the population as a whole. Just think for a minute of all the people you see on these streets every day staring at their phones as they walk down the street, or with their earbuds in their ear, then think of how few are staring at a printed page instead. Yet reading is powerful. From my earliest days of working as a high school teacher, I’ve been telling kids that those who read can learn to write, and those who can do both will eventually succeed in the world. Readers learn to be fair, and writers learn to think. They are the crucial counterweight to those that are close-minded and mean-spirited. Too many of those are currently in positions of power, their poverty of thought best expressed in that intellectual dead zone known as Twitter, where clear thinking and kindness is too often replaced by schoolyard taunts. Not to mention bad spelling and bad grammar.

My wife and I believe—because we’re hopeful people, I suppose—that acting locally eventually, you know, creates change globally. So we give mostly in our own state, and in large part to small town libraries. We support free expression, because without it, the purveyors of fake news—those angry and fearful false prophets—will be believed too much by too many. Tabby and I raised three children, two of whom are here tonight, and four grandchildren, one of whom is here tonight. We urge them all to read banned books, because—I have said this over and over and over again—what the people in charge don’t want you to know, that’s what you have to find out.

I don’t much like to talk about what we do in the way of philanthropy; I don’t even like the word, which sounds like it has something to do with collecting stamps. I was raised Methodist, and two of the Biblical commands that I grew up with were these: pray in your closet, not in the street, and let not your right hand know what your left hand doeth. Even being here feels . . . not wrong, exactly, because this is the second time I’ve had a chance to wear this monkey suit. Anyway, being here doesn’t feel wrong, exactly, but lacking humility, and giving should be humble. At the same time, it’s important to serve as an example. To be able to say, “I am doing this because it’s right, and it’s important.” If you feel the same way—and because you’re here tonight, I’m sure you do—then go and do thou likewise. Thank you.