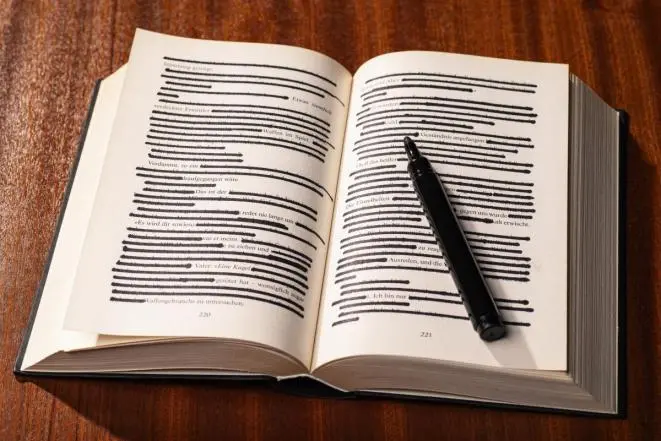

How So-Called DEI Bans Serve as Pretexts for Censorious Takeovers of University Governance

Monthly Roundup, May

This post is part of a series from PEN America tracking the progress of educational gag orders and censorious legislative efforts against educational institutions nationwide. These bills are tracked in our Index, updated weekly.

May has been a prolific month for new educational gag orders. Three new laws of this type have been adopted thus far, with several more appearing imminent. After reviewing these gag orders in this month’s Roundup, we examine some of the most newsworthy, most extreme, and most censorious bills targeting higher education today: Florida’s SB 266, Ohio’s SB 83, and other so-called “DEI ban” bills. We find that, in reality, these bills go far beyond banning DEI initiatives to enable the partisan takeover of many aspects of university governance.

- Since January 2021, 306 educational gag order bills have been introduced in 45 different states

- 26 have become law in 17 states (3 are not currently in effect)

- 2 additional states have enacted educational gag orders via policies or executive orders

- 125 million Americans live in the 20 states where an educational gag order is in effect

- 81 educational gag orders are currently live

Of those currently live:

- 74 target K-12 schools

- 22 target higher education

- 38 include an avenue for punishment for those found in violation

New Laws and State Policies

- Florida’s SB 266 prohibits public colleges and universities from expending any state or federal funds on any program or campus activity that violates last year’s HB 7 (the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act”), that advocates for diversity, equity, and inclusion, or that promotes or engages in political or social activism. Governing boards will now be required to review their institutions’ mission statements and curricula for violations of the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, as well as for programs that are “based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, or privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, or economic inequities.” General education courses may not “distort significant historical events,” teach “identity politics,” violate the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, or be “based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, and economic inequities.”

- Florida’s HB 1069 prohibits public K-12 staff from using in reference to themselves a preferred personal title or pronoun when communicating to a student if that title or pronoun does not correspond to the staff member’s biological sex. No classroom instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity may be offered in pre-K to grade 8. All instructional materials used as part of a health studies curriculum must classify individuals according to their biological sex and receive approval from the State Department of Education. Any parent or resident of a county may challenge material contained within a school, including if the material allegedly “depicts or describes sexual content.” Material challenged for being “pornographic” or for containing “sexual conduct” must be made immediately inaccessible to students pending the outcome of an investigation.

- Indiana’s HB 1608 prohibits public K-12 schools from providing any instruction related to “human sexuality” in pre-K to grade 3.

DEI Bans and Partisan Control

Bills that purport to ban DEI initiatives on college campuses are currently in vogue in state legislatures. Their proponents describe them as straightforward “DEI bans.” For example, Florida governor Ron DeSantis declared during the signing ceremony for SB 266 on May 15, “This bill says the whole experiment with DEI is coming to an end in the state of Florida… “We are eliminating the DEI programs.” Major media outlets have picked up this framing in their headlines as well when covering these bills – including the New York Times and the Washington Post in covering SB 266, and the Associated Press and Axios when covering Ohio’s SB 83, another prominent bill of this type.

This framing is incomplete: it seriously understates the scope and impact of these bills. The legislation does in fact ban diversity and inclusion programs and offices on campus. But bills like Florida’s SB 266 and Ohio’s SB 83 also reach into many other areas of governance typically determined by universities themselves: curricula, tenure, accreditation, mission statements, and more. Ultimately, these anti-DEI laws are best understood as representing a significant threat to the autonomy of colleges and universities from direct partisan or political control – an aspect of higher education recognized by international authorities as essential to guaranteeing free expression on campus.

To understand the connection between DEI bans and institutional autonomy, it’s best to start with where campus DEI initiatives originate in the first place. It’s true that some diversity, equity, and inclusion programs are externally imposed – through federal or private grant requirements or by state governments, as, ironically, happened at New College of Florida less than three years ago. But many also arise organically from within colleges and universities themselves. Numerous colleges have embedded diversity goals in their mission and vision statements and strategic plans, documents typically approved through mechanisms of shared governance between administrators, faculty, staff, and other campus stakeholders.

For example, Florida State University’s mission and vision statements describe the institution as one that “embraces diversity,” “a welcoming place where people discover others like themselves—while also connecting to and learning from classmates and colleagues of vastly different backgrounds and experiences.” The institution’s “distinctive climate…draws from the rich intellectual and personal diversity of our students, faculty, staff, and alumni.” “Diversity and inclusion” was one of FSU’s five central goals in its just-completed strategic plan, and still forms a key portion of one goal in the new plan. Under these documents, to restrict DEI initiatives by legislative fiat effectively violates Florida State’s self-determined mission and goals.

Those in favor of outright bans on DEI programs have expressed skepticism when it comes to autonomy for universities and colleges deciding their own missions and values. As anti-DEI advocate Adam Kissel put it in The Federalist, “When public colleges fail to [determine institutional priorities] effectively, it is appropriate for legislatures to fill the gap.” Essentially, campus communities should only be able to make governance decisions if those decisions align with the viewpoints of politicians in the state legislature. Once applied to DEI and critical race theory, this approach can easily spill over into many other aspects of university governance.

To be clear, defending against outright bans on everything related to DEI is not an endorsement of every DEI-related office, program, or initiative. Far from it. PEN America has repeatedly criticized some university DEI practitioners for censorious overreach on issues involving academic freedom and free expression, including high-profile cases within the past year at Hamline University and Georgetown University. Too often, some DEI professionals have pitted free expression and diversity goals against one another in unproductive and censorious ways. But legislative bans on such initiatives are not a reasonable solution to these challenges. Almost inevitably, they will be too broad and will ban too much. They also set a dangerous precedent, opening the door to further politicized interference in academic affairs.

Florida’s SB 266

This dynamic is on full display with Florida’s SB 266, the first bill of this type to become law in 2023. SB 266 does indeed ban DEI initiatives. But it does so much more.

Bans a broad swath of only tangentially DEI-related initiatives. In its own language, SB 266 prohibits the use of federal or state funds for any “programs or campus activities” that “advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion,” as well as any form of “political or social activism.” But because those terms are not defined in the law, the measure risks defunding much more than diversity training, multicultural celebrations, and traditional DEI offices. Indeed, according to information submitted by university leadership, everything from Florida A&M University’s Institute of Public Health’s outreach initiative for poor and underserved Floridians to its Campus Safety Workshops offered by the Chief of Police could lose state support.

Expands the Stop W.O.K.E Act. HB 7, the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act,” became law in Florida in 2022. It prohibits public colleges and universities from “subjecting any student or employee to training or instruction that espouses, promotes, advances, inculcates, or compels” belief in certain concepts related to race, sex, color, or national origin. These provisions of HB 7, which PEN America argues are blatantly unconstitutional, have been enjoined by a federal judge and now await consideration by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

SB 266 prohibits the use of state or federal funds “to promote, support, or maintain any programs or campus activities” that violate the Stop W.O.K.E. Act. Whereas the original focus of HB 7 was only on training and instruction, this new provision radically expands its scope to anything and everything involving the use of public money. This could include programs and activities by student groups, faculty research and publications, public lectures and debates, internships, membership in scholarly organizations, conferences and symposia, and candidate forums.

The law does provide some limited exceptions. For instance, student fees are exempted, as is any program or activity required by an accrediting agency – though as will be explained below, the impact of this last exception is essentially nil. Regardless, the shadow cast by SB 266 will be enormous. In its incredible breadth, it runs rough-shod over numerous forms of free expression on campus.

Restricts general education curricula. SB 266 also includes unprecedented restrictions on general education courses, including bans on “identity politics” and “distort[ing] significant historical events” and instructional content “based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, and economic inequities.” This vague and sweeping language is ripe for abuse and will certainly have a chilling effect in the classroom. It is also likely to impact the way universities develop and approve their general education curricula – another common feature of legislative overreach into university governance processes.

Further erodes faculty tenure. Florida’s SB 7044, passed in 2022, imposed new restrictions on how colleges and universities may manage their faculty tenure systems, a function that was previously governed by the institutions themselves. SB 266 builds on this law by eroding faculty tenure even further. In Florida, public college and university faculty are represented by the United Faculty of Florida (UFF). Each institution has its own chapter, which negotiates with its Board of Trustees to establish a collective agreement for issues like salary, working conditions, and discipline. If faculty members believe that their rights have been violated – for instance, their contractually negotiated right to academic freedom – they may submit their grievance for binding resolution by an independent arbitrator.

No longer. Under SB 266, “personnel actions or decisions regarding faculty, including in the areas of evaluations, promotions, tenure, discipline, or termination, may not be appealed beyond the level of a university president or designee.” In other words, no more binding arbitration. When paired with last year’s SB 7044 and the state regulations that followed, this means that faculty who believe that they were disciplined for engaging in protected speech are out of luck, including speech barred by the Stop WOKE Act. The university president’s decision is now final.

This is not a hypothetical in Florida. In 2021, the University of Central Florida fired Charles Negy, a tenured professor who drew national attention following the death of George Floyd for tweets about reverse discrimination and “black privilege” that critics deemed racist. Negy’s termination made him a cause celèbre within conservative media and was dubbed the “anti-woke professor”. But UFF filed a grievance and in 2022, an arbitrator ordered UCF to give Negy his job back. It was an unqualified victory for Negy, his faculty union, and academic freedom. It is also the sort of thing that, under SB 266, will no longer be possible.

Undermines university accreditation. SB 266 makes a change to Florida’s laws around higher education accreditors that, while seemingly minor, has major implications for academic freedom and free speech. Under the new law, accrediting agencies “may not compel any public postsecondary institution to violate state law” nor take any “adverse action” against a university for acting in compliance with state law. Furthermore, last year’s SB 7044 permitted colleges and universities to sue accrediting agencies in response to harm caused by “retaliatory action.” SB 266 goes further, empowering universities to sue over any “adverse action” as well.

This is about intimidation. As PEN America argued in our initial analysis of last year’s SB 7044, Florida’s government is concerned that an accrediting agency might respond to violations of academic freedom by downgrading a postsecondary institution’s accreditation. Indeed, after the University of Florida blocked three of its professors from providing testimony deemed harmful to the state’s interests, the university’s accrediting agency launched an investigation. Further investigations are likely in the event that the judicial stay on the Stop W.O.K.E. Act is lifted. But the provisions in SB 7044 and SB 266 offer a powerful defense for censorious universities against accreditors. Should an accrediting agency follow through on an accreditation downgrade (which would affect everything from student retention to access to federal grants), it would be liable under the laws for significant damages.

Rewrites university mission statements. Finally: what of the concern that these provisions would force universities to violate their own mission statements by banning diversity programming? No matter. Those mission statements will no longer be the responsibility of universities, but of the Board of Governors, who under SB 266 are now empowered to “periodically review the mission of each constituent university and make updates or revisions as needed” – no shared governance required.

Ohio’s SB 83 and Other “DEI ban” Bills

Outside of SB 266, Ohio’s SB 83 is likely the most censorious “DEI ban” bill currently under serious consideration. The state senate recently approved SB 83, a bill based in large part on model legislation by the conservative National Association of Scholars. Like Florida’s SB 266, SB 83 does in fact ban DEI initiatives, but it would do much more besides, placing restrictions on tenure, curricula, classroom instruction, and more.

With limited exceptions, SB 83 would prohibit “any mandatory programs or training courses regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion.” It would also forbid “political and ideological litmus tests in all hiring, promotion, and admission decisions, including diversity statements and any other requirement that applicants describe their commitment to a specified concept, specified ideology, or any other ideology, principle, concept, or formulation that requires commitment to any controversial belief or policy.” Universities would also be barred from using “a diversity statement or any other assessment of an applicant’s political or ideological views in any hiring, promotions, or admissions process or decision.”

This is powerfully chilling language. The bill does offer definitions of “controversial belief or policy,” “specified concept,” and “specified ideology,” but they are vague and non-exhaustive; the definitions also include terms as anodyne as “sustainability,” “inclusion,” and “marriage.” Most likely, the bill’s authors have in mind something like a requirement that job applicants affirm their belief in “white fragility” or some other widely contested concept. But SB 83 would also prohibit universities from asking would-be professors how they would support first-generation students, create an inclusive learning environment for the disabled, and supervise students from diverse backgrounds. These sorts of questions cut to the core of what being a university professor is all about, yet lawmakers have devised a bill that would place those asking such questions in jeopardy.

SB 83 would also prohibit faculty and staff from seeking to “inculcate any social, political, or religious point of view,” a ludicrous provision that would compel faculty to calculate whether, in the course of their teaching to students, they are being impermissibly persuasive. Universities and all their constituent units would be charged with “ensur[ing] the fullest degree of intellectual diversity” on matters like course approval, general education requirements, common reading programs, strategic goals for departments, student learning outcomes, and invited speakers. To that end, they would also be forbidden from adopting an institutional position on any “belief or policy that is the subject of political controversy.” The bill also contains tenure restrictions and mandatory post-tenure reviews very similar to those now in effect in Florida after passage of that state’s SB 7044 and SB 266.

Finally, universities would be forced to discipline any member of the university community, including students, who in the judgment of some university authority “interferes with the intellectual diversity rights… of another.” This is outrageously vague language and could include academic choices made by teachers, where faculty are charged with using their “professional judgment” to expand intellectual diversity and disciplined if that judgment is “misused to constrict intellectual diversity.” What this entails is unclear.

In fact, the entire bill lacks clarity or precision. Writing on behalf of Ohio’s fourteen public universities, the Intra-University Council of Ohio warned in a letter to legislators that SB 83 “could potentially chill protected freedom of expression.” It would also saddle universities with a costly administrative burden and layers upon layers of new bureaucracy. “What constitutes ‘interference’ with ‘intellectual diversity rights’ is not established in common law. Legal expenditures and increased administrative support by individuals with requisite knowledge of statutory construction and constitutional law will be necessary to pursue sanctions through an appropriate process, which affords any potential respondent with required due process.”

Similar problems can be seen in other anti-DEI bills, including Texas’s SB 17 (which would prohibit universities from even asking somebody for their thoughts about diversity, equity, and inclusion), Arizona’s SB 1694 (which would forbid public universities from adopting an official position related to “neopronouns,” “disparate impact,” “group marginalization,” and “inclusive language”), and Iowa’s HB 616 (which contains elements from both of the preceding bills and combines them with a right of private action that extends to students, faculty, and alumni).

The Texas bill, which appears likely to become law, merits special attention. Introduced as part of a three-bill package that included an educational gag order and a ban on university tenure, SB 17’s initial version featured some eye-popping – and now deleted – language that would have established a formal statewide blacklist for university faculty or staff determined to have engaged in illicit DEI wor, along with language similar to Florida’s SB 266 targeting university mission statements and general education courses. While these passages have since been removed, the bill now includes threatening language toward accreditors that appears to be copied almost verbatim from Florida’s SB 266.

Conclusion

On May 3, Christopher Rufo, perhaps the chief architect of educational gag orders at both the K-12 and college levels, surprised listeners at a Stanford event by commenting that “critical race theory bans should be limited to K-12.” “If my kid is in college,” he said, “let it rip, free rein, let’s have a debate. … I think what happens in classrooms, leave it alone, and for conservatives that’s probably a losing fight.” Instead, he continued, at the college level “conservatives should focus on administration and governance.”

Rufo’s comments are borne out in this year’s crop of higher ed gag orders, which, while not abandoning classroom restrictions, have moved toward a focus on restricting the governance processes of colleges and universities. Both curricular restrictions and DEI bans follow this model. Because their advocates dislike the choices many colleges have made to invest in diversity, equity and inclusion programming and to include courses on race and gender in core curricula, they seek not only to reverse those choices, but to take away the ability of university communities to make governance decisions on their own behalf. In doing so, they place public colleges under direct political control – something guaranteed to create a profound chilling effect across every public college and university campus.

This update from PEN America was compiled by Jeffrey Sachs and Jeremy C. Young.