I am constantly reminded of the importance of “snail mail” through my position at PEN America, as I’m greeted by a tall stack of envelopes sitting on my desk when I arrive at work each day. Most of these letters contain numerous pages of handwritten submissions to our annual PEN Prison Writing Contest, requests for our program information, and reflections on the power of the writing as an emancipatory, healing outlet. Within this daily stack of mail, however, I expect to find a sizable amount of envelopes marked as “Return to Sender.” While there are many reasons why mail gets rejected and never makes it to its intended recipient, the reason usually involves an incarcerated person being relocated to a different facility, or changes in mail policies that reflect an increasing effort to censor correspondence through the walls.

Beneath the broad claim of safety regulations, carceral facilities across the country are rapidly implementing mail procedures that severely restrict what’s allowed inside. Despite physical correspondence being a fundamental method of communication for incarcerated people, the process of mailing letters, books, and other materials is often thwarted by a myriad of institutional constraints, including arbitrary guidelines and extreme censorship measures. These policies vary by state, and often by facility within a state, contributing to the complexity of sending mail inside. While Georgia state and federal prisons, for instance, accept standard letters and other forms of correspondence, the DeKalb County Jail has enforced strict mail requirements since 2012, which only permits white postcards that are sized between 3.5”x4.25” and 4.25”x6,” written in blue or black ink, and have a metered or pre-printed stamp. Except for legal mail, any other type of correspondence, even if the postcard is only marked with paint, crayon, or markers, will be rejected from the facility.

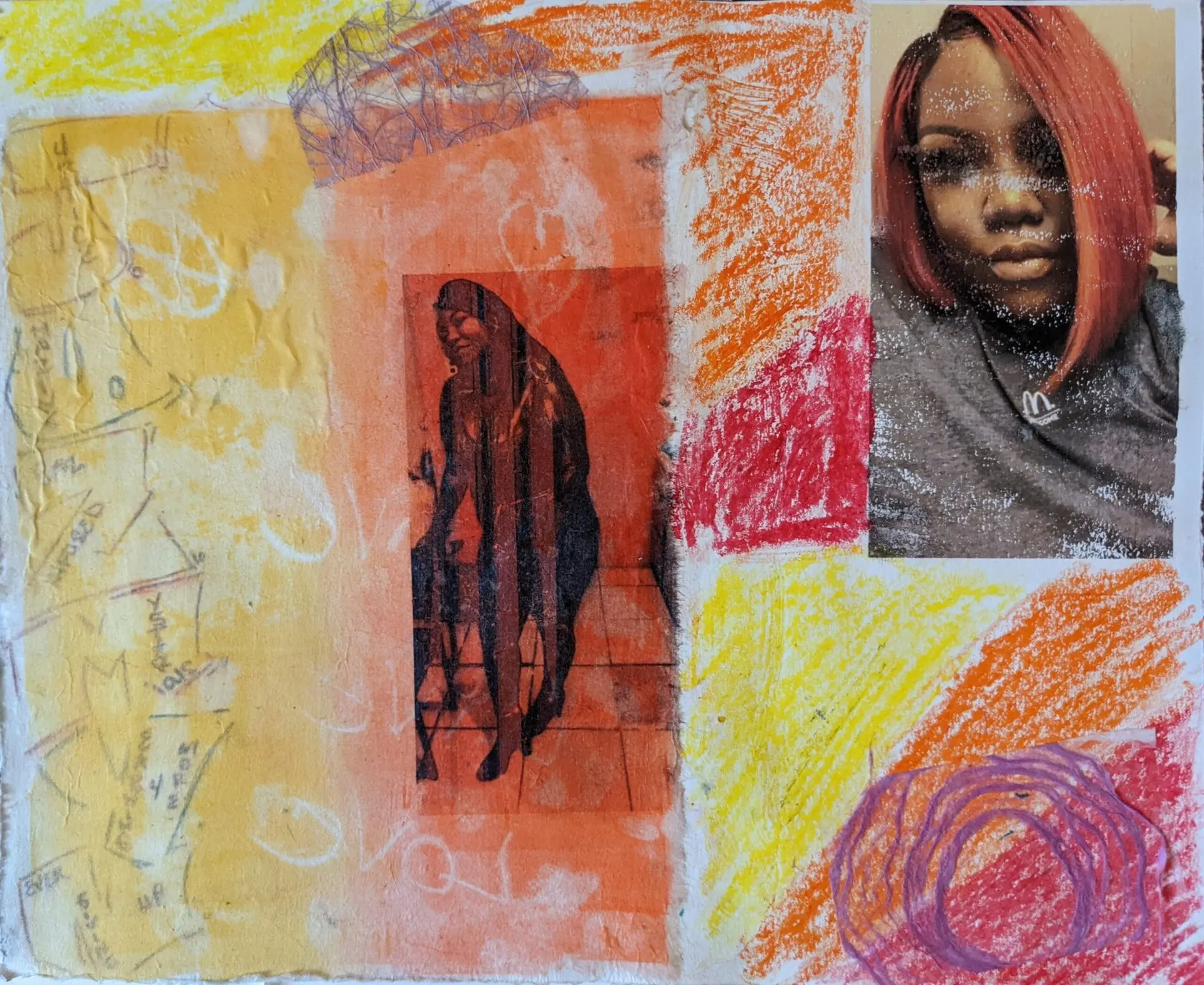

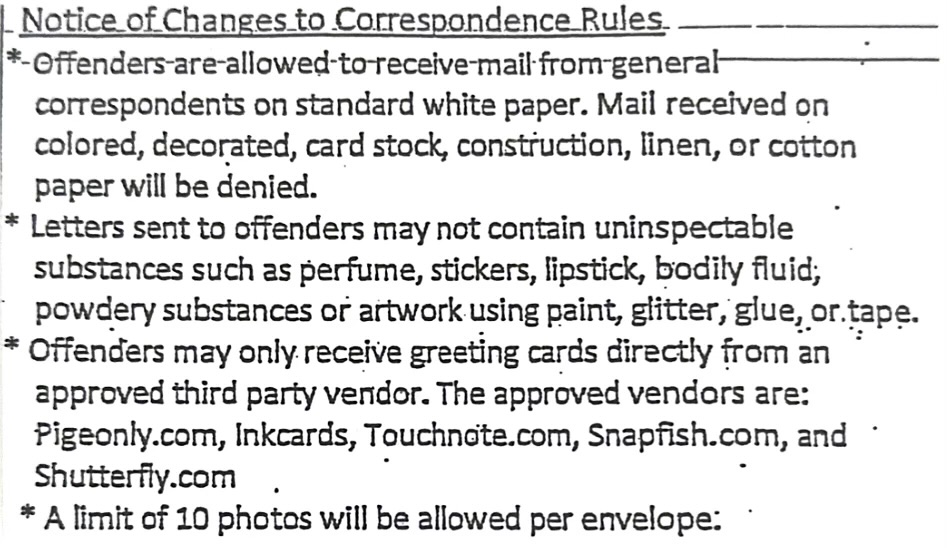

I got a closer look at strange prison mail rules when I noticed a small slip of paper within several of the envelopes I received from people incarcerated in Texas. The 4”x2.5” page outlines a list of the recent changes in correspondence guidelines, which severely restricts the amount of material allowed inside. The denial of color and artwork in accordance with these rules is specifically important to note. Much of the letters and envelopes I open are adorned with colorful, detailed drawings, which not only highlights the creativity often hidden beneath the shadows of carceral confinement, but also the desire to break through the desolation and bleakness of life behind the walls. Mail policies that prevent incarcerated individuals from receiving mail with color and artwork, also deprive them of imagining and experiencing beauty beyond what they can access in their immediate surroundings.

Aside from prohibitive mail procedures, one of the most concerning issues surrounding physical correspondence and prison is mail digitization. In recent years, states have increasingly banned all forms of physical mail— handwritten letters, cards, printed resources, and artwork— and alternatively provide a copy of these items to recipients. The mail scanning process varies by state, but primarily functions in one of two ways: carceral facilities either hire a third-party vendor—such as Smart Communications, Securus, or TextBehind—to scan and deliver copies of the mail, or letters are scanned internally, relying on prison staff or the labor of incarcerated individuals. A person incarcerated in Pennsylvania, which has been utilizing Smart Communications for mail scanning since 2018, sent me an informational sheet that details which address to send mail to according to material of the correspondence. The several different addresses listed underlines just how needlessly complex sending mail to prisons and jails could be.

Prison and jail administration purport that mail scanning aids are an effort to prevent contraband, namely drugs, from entering the facility. But, as a report on mail scanning by the Prison Policy Initiative explains, there is not only no substantial evidence to support these claims, but mail digitization also relies on exploitative tactics that target incarcerated individuals and their families. Once the correspondence is scanned, depending on the facility, people inside either receive printed copies or can only access their mail on tablets or community kiosks issued by state Departments of Corrections. These scans, both printed and digital, are often flawed and insufficient, as they may be produced in grayscale only, become blurry and thus unreadable, or even have cut-off words and sentences. Because of the poor quality of scanned mail, families may feel encouraged to use other, more expensive means of digital communications, making it even more difficult for people inside prisons to preserve ties to the outside world.

An incarcerated person in a West Virginia federal facility wrote to me expressing his concern over missing information due to mail digitization:

I regret to inform you that the Federal BOP provides incarcerated individuals one copy of incoming mail, and discards the originals. Here, the mailroom staff are only willing to photocopy one side of the paper of incoming mail regardless of the complaints from the inmate population. That being said, the mailroom staff threw away half of the information that PEN so graciously sent me.

Many states implement similar restrictions on the amount of mail permitted to be scanned and distributed, like Arkansas, which only allows incarcerated individuals to receive two 8.5”x11” sheets of grayscale, printed copies of their mail. As the official policy states, these pages “include a copy of the envelope and three pieces of the correspondence on the four-sides of the two sheets of copy paper.” This extremely convoluted language makes it difficult to determine what is actually permitted inside, which may cause an increased volume of rejected mail. Any correspondence that does not adhere to the state’s guidelines “will be treated as contraband,” and the recipient has “thirty (30) days to pay for return postage or it will be destroyed.” A person inside an Arkansas facility sent me a letter explaining how these restrictions hinder his ability to receive requested resources:

Please be informed that my institution is not allowing me to receive your correspondence because, regardless of the federal postage you pay to ship your correspondence, they say I am only allowed to receive a certain number (3) one-sided sheets of text per envelope. I am not unique in this plight- everybody at this institution and as far as I know, in this state, is mistreated and has our mail suppressed in this manner.

The increasing challenges of sending mail to incarcerated individuals merely perpetuates the dehumanization that lies at the foundation of carceral confinement. Under the guise of safety regulations, states are banning often the only tangible connection incarcerated people have to the outside world— connections that are crucial for survival on the inside as well as upon reentry. The exploitative and inhumane mail policies must end, as incarcerated people deserve unrestricted access to their loved one’s letters, cards, and photographs— which, for many, are a lifeline.

Jess Abolafia is the Prison and Justice Writing Program Assistant at PEN America. She graduated summa cum laude with a BA in English and African-American Studies from The College of New Jersey, where she also received an MA in English. Abolafia has instructed a writing-workshop at the only women’s maximum-security prison in New Jersey, empowering incarcerated women to use writing as a tool of healing and liberation. She is also working on several book projects with system-impacted individuals, including co-editing the memoir of an incarcerated woman sentenced to life in prison as a teenager, and compiling the paintings, drawings, and poems of an artist who found freedom through his artwork during nearly four decades of incarceration, including eight years on Death Row.