Introducing “Unsealed:” Inside the Letters of PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program

Severed Sentences: The Precarious Process of Communication through the Walls

In 2020, amidst a global pandemic and growing uncertainty, my English professor invited me to work on a book project with a woman who has been incarcerated for nearly 30 years after receiving a life sentence as a teenager. The entire project, a memoir, would live through postal mail, relying on envelopes and stamps to exchange hand-written letters, drafts, and feedback for each chapter. After eagerly agreeing to the project, I gathered all of the materials I needed to write my first letter: a fresh black ballpoint pen, crisp white envelopes, and a roll of stamps. I also decided to use paper with a vibrantly colored, floral border in hopes of disrupting the muted beiges and grays of prison. After weeks of sending out my letter, I finally received a response. The long envelope, marked with a red DOC label and cradling the letter within it, was my first tangible connection to someone inside of a maximum-security facility, and the catalyst for what would become a meaningful, joyful, and enduring friendship made possible only by handwritten mail.

For the 2.2 million people inside of carceral facilities across the United States, physical correspondence is often the only means of maintaining palpable connections to the outside world. Sending letters, writing drafts, and other items through postal mail, however, is a precarious process. The challenges of written mail have become increasingly apparent to me in my current position as the Program Assistant for the Prison and Justice Writing Program at PEN America. Sifting through the mail that lands on my desk each day, I read many letters asking if I have received a request for our recent publication, The Sentences that Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison, or a submission to our annual PEN Prison Writing Contest. While many people on the outside can typically communicate such questions through email or phone calls, people subjected to incarceration don’t have the luxury of unlimited access to quick messaging. Exploitive carceral practices make the price of digital stamps and timed phone calls expensive, leaving the physical mail the most widely accessible method of communication for people on the inside. There are then minimal to no ways to track envelopes as they travel to and from institutions, and the length of time it takes for mail to be received can be anywhere from weeks to months.

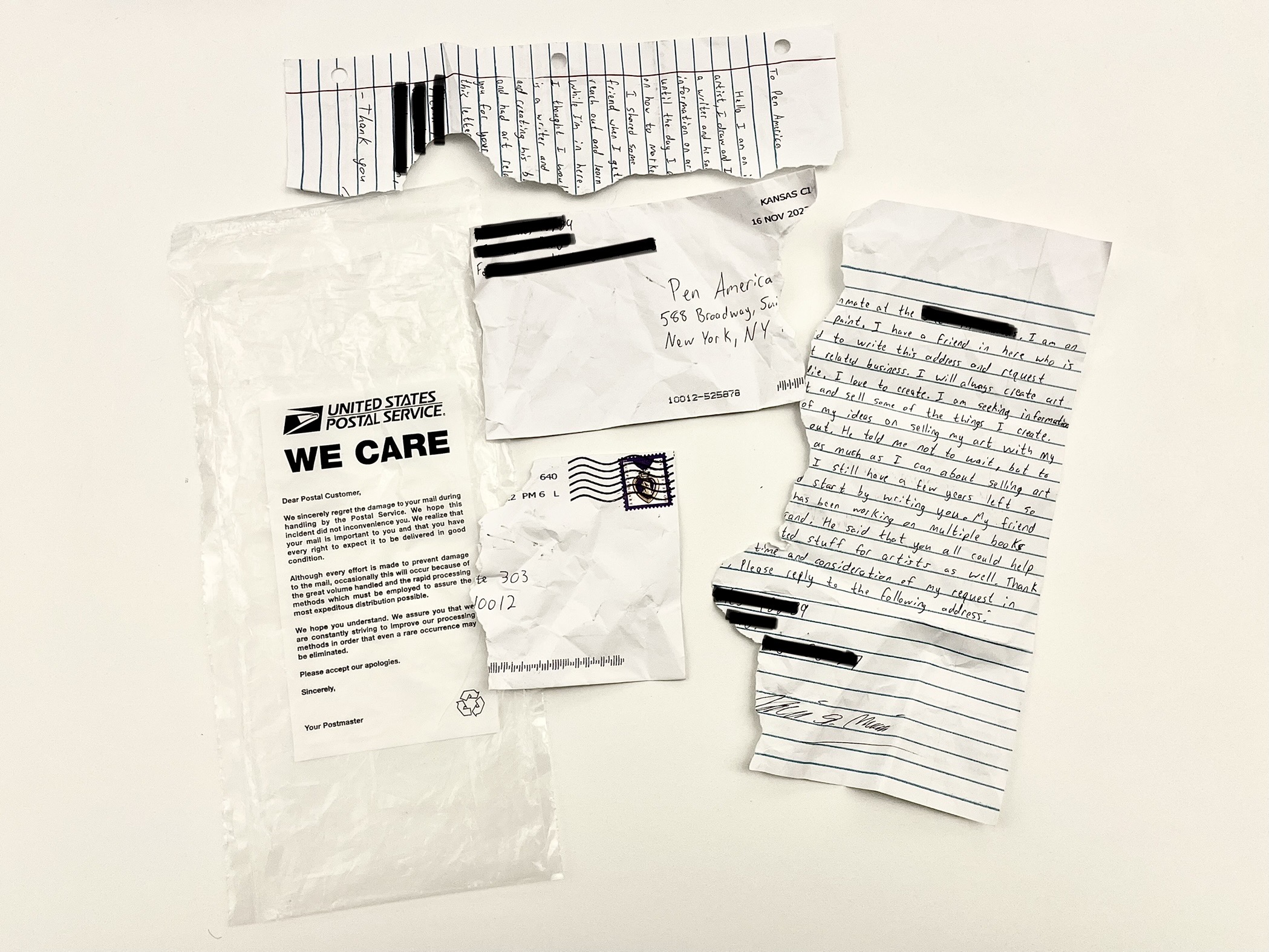

During the time that it takes for letters to pass through highly-secured mailrooms and multiple postal municipalities, there is always a chance that the line of communication may be disrupted. In addition to the general possibility of envelopes getting lost in the mail, the rampant censorship practices within carceral facilities cause several letters to arrive on my desk damaged or already opened. Numerous letters are also returned to me before even reaching an institution, and are often vandalized and marked with dark strikethroughs by prison staff, making it nearly impossible to discern the name and address of the person for which the mail was intended.

One of the most notable pieces of mail I have received is an envelope that was torn in half, directly down the middle. The ripped papers, including the handwritten letter within the envelope, were sealed inside of a slim plastic bag labeled “We Care” in bold black letters. Although it is difficult to determine if this mail was damaged intentionally by prison staff or simply by mistake, it serves as a powerful visual metaphor. The reality of handwritten communication is clear: while physical correspondence is the primary vessel that sustains connections between incarcerated individuals and the outside world, it is always at risk of being disrupted by the different hands through which the mail has to pass. The layers of uncertainty that surround handwritten mail contribute to the harsh isolation and silencing of imprisonment; incarcerated people seal their letters with hope that they will reach its final destination, but face a perpetual chance that their voices will still be constrained, despite their words flying beyond the physical confines of the walls.

For the past five decades, the mail has been at the center of PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, serving as the fundamental tool of communication to budding and flourishing writers behind bars. With “Unsealed,” a new column for PEN America’s Works of Justice newsletter, we shed some necessary light on the integral and unique role that handwritten correspondence holds. In a space that crushes personal autonomy, where the tangible holds a special significance, increasing mail digitization in carceral facilities across the country puts the centrality of physical correspondence at risk of being lost. This column seeks to preserve the legacy of handwritten mail by celebrating, uplifting, and sharing the creativity that we discover as we unseal its envelopes. We invite you to join us in this process of discovery.

Jess Abolafia is the Prison and Justice Writing Program Assistant at PEN America. She graduated summa cum laude with a BA in English and African-American Studies from The College of New Jersey, where she also received an MA in English. Abolafia has instructed a writing-workshop at the only women’s maximum-security prison in New Jersey, empowering incarcerated women to use writing as a tool of healing and liberation. She is also working on several book projects with system-impacted individuals, including co-editing the memoir of an incarcerated woman sentenced to life in prison as a teenager, and compiling the paintings, drawings, and poems of an artist who found freedom through his artwork during nearly four decades of incarceration, including eight years on Death Row.