Unsealed: The Blood and Ink of the Prison Pen

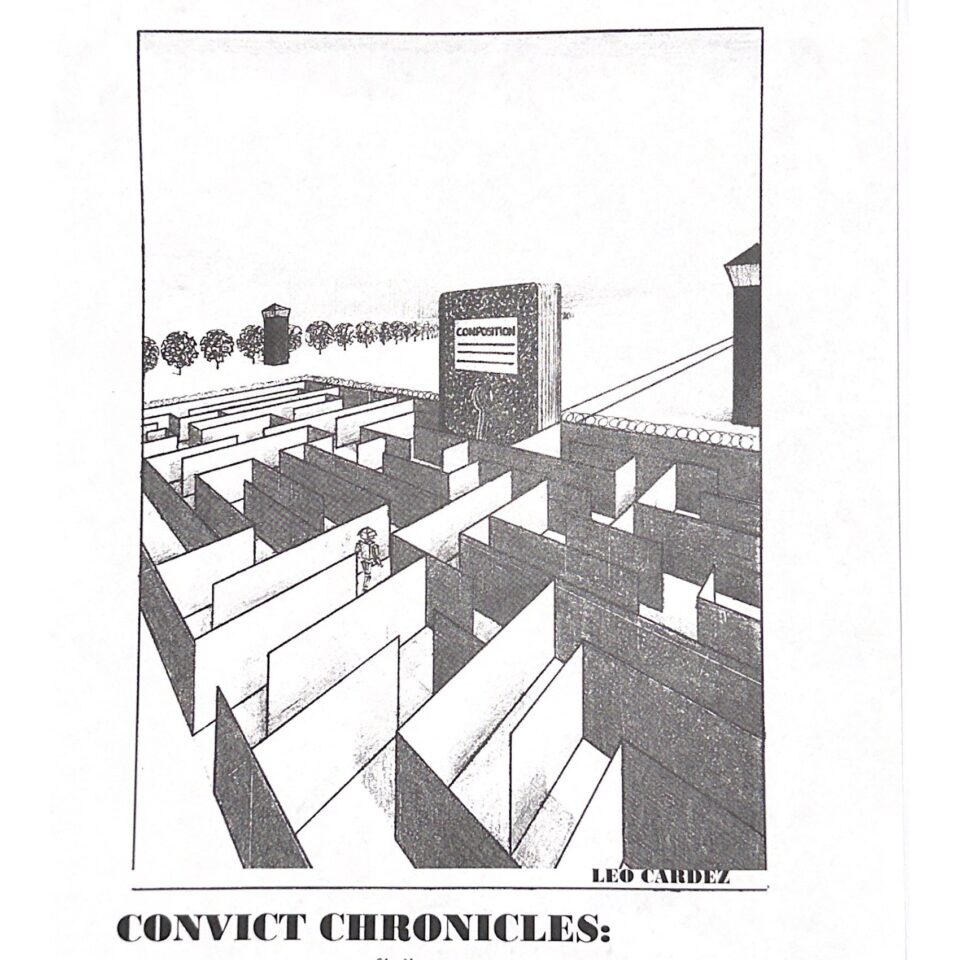

Within carceral environments—fundamentally designed to surveil, punish, and silence—writing is an emancipatory endeavor. It is not only a common outlet of cathartic healing, but it has the ability to break through the isolation and opacity of carceral confinement by lifting the voices and lived experiences of people on the inside.

Perhaps this power inherent in the written word is why prisons and jails across the country restrict access to resources that would otherwise help imprisoned individuals develop their craft as writers. Purchasing writing materials can be prohibitively costly, and rampant censorship practices limit the amount of educational material available to enhance writing skills. In a letter explaining the limitations he personally encounters, an incarcerated person in Wisconsin explains that it is difficult for his writing to reach a broad audience without access to the internet, not to mention his research abilities are limited without a functioning library in the prison. For three years, he has also been unable to receive any books from external vendors, such as Amazon, due to fallacious concerns of “smuggling.”

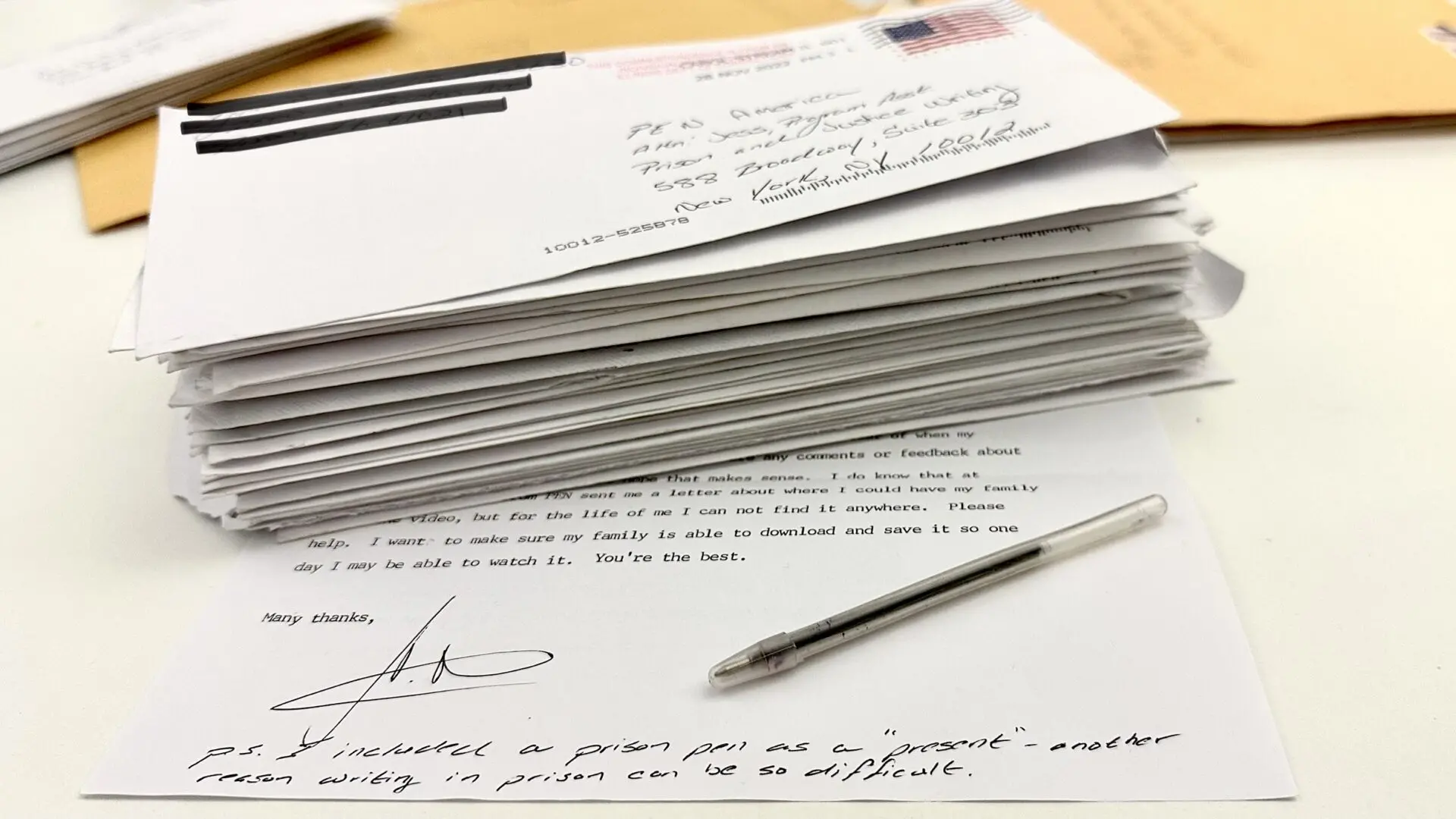

Despite the myriad limitations of writing while incarcerated, people on the inside often pursue any means necessary to exercise their freedom to write. The hundreds of submissions to our annual PEN America Prison Writing Contest alone show the extent writers behind bars are willing to take to get their voices heard, even if that means facing potential retaliation from prison staff, writing hundreds of pages by hand, or enduring physical pain from the insufficient materials at their disposal.

Leo Cardez, an avid writer and two-time contest winner, tucked the pen uses to write his essays and plays inside of a letter he sent to me, noting that it is “another reason writing in prison could be so difficult.” I asked Cardez to describe what it’s like to work with the four inch, so-called pen, to which he responded with a piece and a few drawings that thoroughly captures the sacrifices people behind bars make to defy the silencing shadows of carceral confinement.

Jess Abolafia

Program Assistant, Prison and Justice Writing

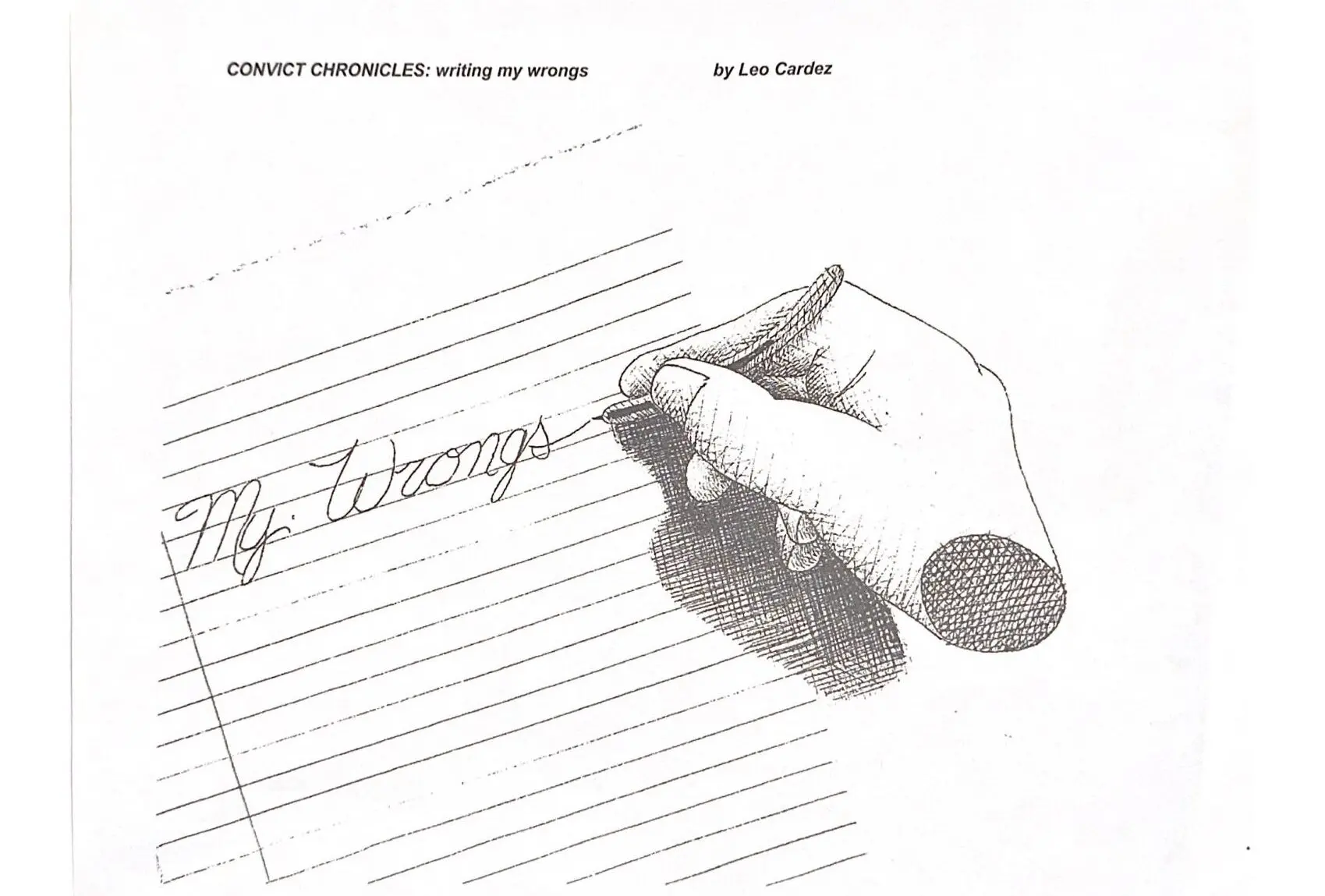

Imagine that you are driven to the page by an unspeakable force that demands blood.

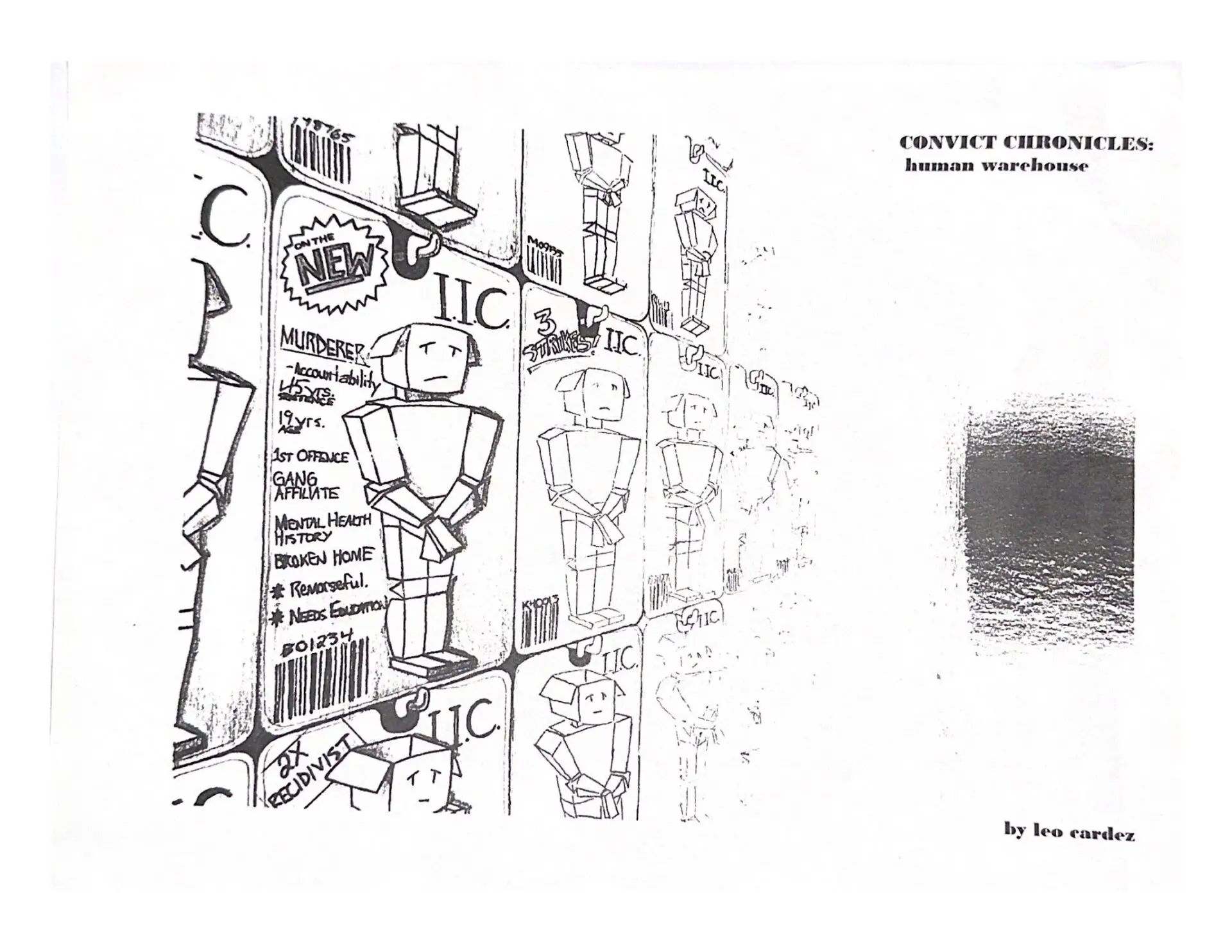

Forget that you have been deemed sub-human and are warehoused on the fringes of society without access to computers, copiers, or the internet.

Imagine that writing your little stories brings you peace and purpose, keeping you from falling so deep in the well you lose all the light.

Forget that your hard steel stool causes you to lose feeling in your butt and legs; forget that your low table causes neck aches that will lock up your back after an hour; forget that holding the torture device known as your seg pen—which is more like the innards of a real pen—has resulted in you being diagnosed with carpel tunnel, requiring steroid shots to alleviate the pain.

Imagine that you won a PEN America Prison Writing Award, were published in an anthology, saw your play produced as a puppet show, received a small financial award, and were assigned a mentor (shoutout to Stephanie). Imagine that your family wrote to tell you they were proud of you for an article you had published in their favorite Christian magazine. Imagine feeling as if the sun shone on you from all sides. Now, imagine it happened again.

Forget the noise that is loud, constant, and overwhelming.

Forget the lighting which has two settings: dim and dimmer.

Forget that you need bifocals, but have been on the waitlist for two years.

Forget having to hide your tears by quickly jumping into the shower.

Forget the smell, like trying to write while stuck in a dumpster during a heat wave.

Forget about the cold in the winter, when you write while wearing every piece of clothing you own.

Forget that typewriters cost $400, typing ribbon $7.50, correction ribbon $17, typing paper $2, pens that last a couple of days $0.50, self-addressed stamped envelopes $0.71.

Forget that you only make $15 a month, scrubbing toilets and cleaning showers for eight hours a day.

Imagine your writing touching one person, just one.

Worth it.

Leo Cardez is a two-time PEN America Prison Writing Contest winner, and a Pushcart Press Prize-nominated inmate activist writer. His drama has been produced or is pending production in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Cardez’s nonfiction has been published or is forthcoming in Harbinger (The N.Y.U. Review of Law and Social Change), Crime Report, Abolitionist, Under The Sun, Evening Review, and Blue Collar Review, among others. Kind notes or offers to collaborate are welcome at [email protected].

Jess Abolafia is the Prison and Justice Writing Program Assistant at PEN America. She graduated summa cum laude with a BA in English and African-American Studies from The College of New Jersey, where she also received an MA in English. Abolafia has instructed a writing-workshop at the only women’s maximum-security prison in New Jersey, empowering incarcerated women to use writing as a tool of healing and liberation. She is also working on several book projects with system-impacted individuals, including co-editing the memoir of an incarcerated woman sentenced to life in prison as a teenager, and compiling the paintings, drawings, and poems of an artist who found freedom through his artwork during nearly four decades of incarceration, including eight years on Death Row.