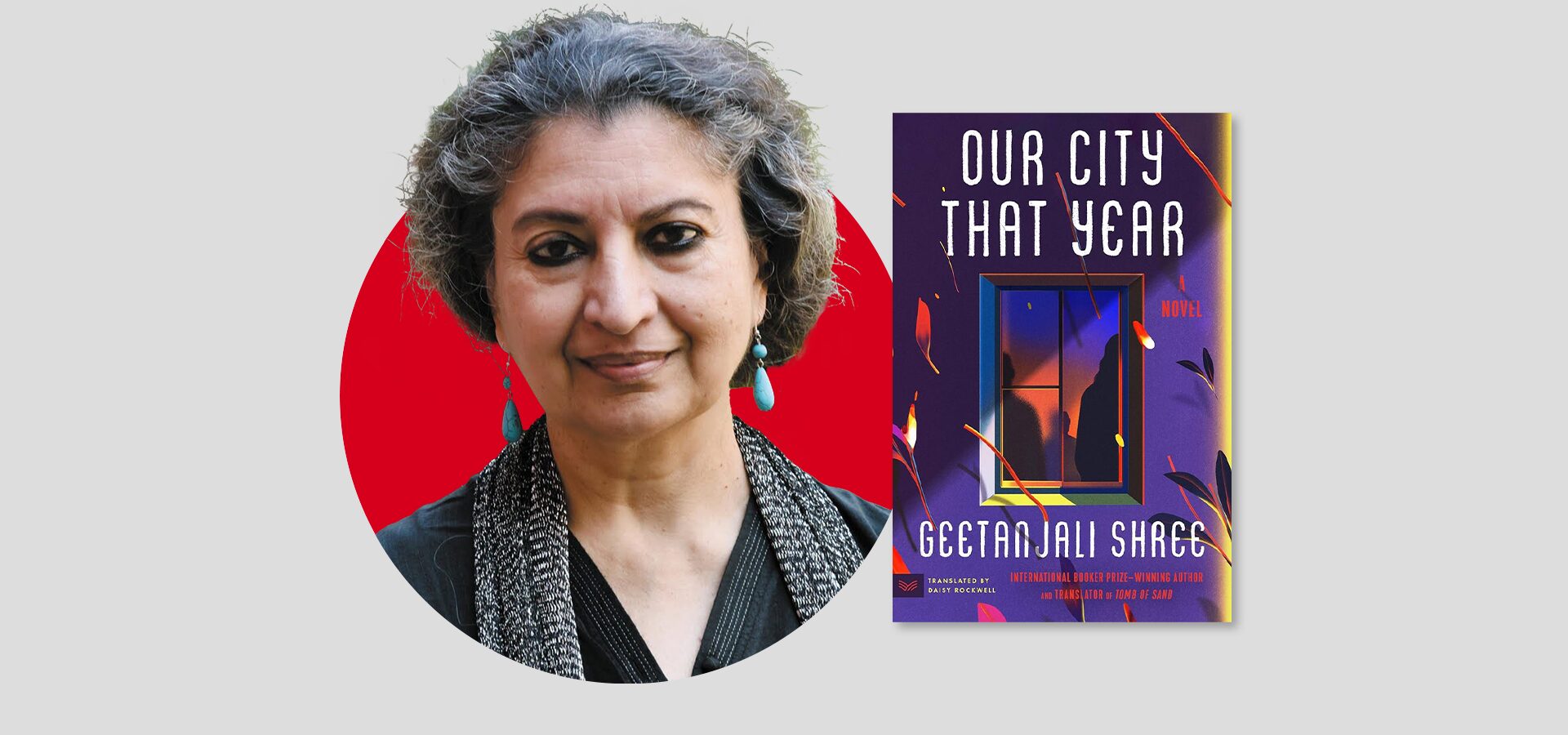

Geetanjali Shree | The PEN Ten

In Our City That Year, set in an unnamed Indian city, an unnamed narrator, in episodic fragments, tells the story of a crisis brewing and ready to boil over. It is in this ambiguity that Geetanjali Shree finds not only her story but the ability to push literature to do what it does best—go beyond the specifics and the immediate.

First appearing in Hindi over 25 years ago, the book, now available in translation by Daisy Rockwell, meets its English readers in a significantly changed world. Though the India Shree wrote around has transformed, the division, plurality, and politics of the land has all but deepened, for better and worse. Our City That Year is at once an incisive look into the laws the society should, but does not operate on, and a lesson in history humanity does not seem to want to learn.

We caught up with Shree in celebration of her first book in English since the duo won the International Booker Prize in 2022 for Tomb of Sand. She discussed how fiction operates for her, literature as a political act, and how though the setting, time, and characters seem distinct, they could, in fact, be any time, any place, and anyone. (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

How does it feel to look back on a book you first wrote in Hindi over 25 years ago? How have the times you wrote it in and about, changed or stayed the same?

In today’s world, 25 years is too long a period for times to remain the same. It would have been worrying enough even if they had remained the same, but the times have gone from bad to worse. Not only in India but globally. The disturbing developments that make the novel’s narrative began to plague parts of India in the late 1980s and early 1990s. They were then perceived, wishfully, as the handiwork of an extremist Right. That Right is now the Center. Those disturbing developments have since sprung up all around. Be it North or South, the world today is more intolerant, more pitiless, and more self-righteously deaf to the ‘other.’ Our time is dangerously out of joint.

Our City That Year is written in episodic fragments, set in an unnamed city, narrated by an unnamed narrator. What was the thought process behind these creative decisions?

The fragments evolved as a fitting form for the episodic broken shards of life that seemed to have replaced the continuum of our existence. That captured the truncated nature of events around us and the breaking of smooth links which gave life its semblance of order, meaning and efficiency.

The city is unnamed because the story is not about any single city. It is about how cities, one by one and one and all, are becoming each a replica of the other.

The unnamed narrator also emerged creatively as the kind of witness such times typically have. She is also, typically, un-knowing, i.e., a reliable witness but not, correspondingly, a reliable analyst. Knowing that she is incapable of analyzing, she is content with recording and describing the feelings, responses, and actions of those she is watching. She collects whatever she can of scenes she hears, sees, smells. She picks up confusions, conversations, distress, anger and puts it all down for a future time, a future analyst, to pick up, collate, and make sense of. Critically for the narrative, this witness is somewhat omnipresent but not omniscient.

In your book, the protagonists are not merely witnesses to a changing city as it splinters over communal violence and burns, but they are also active as creative, thinking, and organizing forces. Why was it important for you to have characters who are catalysts and exert agency in a world that is much larger than them and frequently seems out of their control?

That, indeed, is the predicament of the characters in Our City That Year. Maybe that is the human predicament. The condition humans are born in. Acting and being acted upon, with varying degrees of awareness, is what their lives are about. Within that causal dynamics are played out their hopes, aspirations, efforts, and triumphs as also their despair, frustrations, inertia, and failures. Because my concern was to try and understand the brewing of a crisis that threatened to snowball, it was important for me to concentrate on characters who recognized the threat and resolved to stall it. Ironically, for all their understanding and resolve, they themselves began to be, unselfconsciously, inflected by precisely the bigotry, hatred and aggressivity they had set out to stall.

The novel is concerned with this failure, this urgent need to look into our own selves, and try to understand where we have erred or weakened. Face ourselves, our dark deeps, and spot there the same prejudices we accuse the adversary of.

The Babri Masjid riots of 1993 that your novel is based on is a richly documented moment in recent Indian history. Why did you think it was important to view it through a fictionalized lens in Our City That Year?

I was already writing this novel when the Babri Masjid was demolished on 6 December 1992 and riots broke out in different parts of the country. In fact, the novel was started even prior to the first, unsuccessful, attempt that was made to raze the Masjid on 30 September 1990.

So I would not say the novel is about the Babri Masjid. What concerned me frontally was the visible deepening of divisions and mutual suspicions between the two major communities living in independent India. What is it in ‘modern’ times that draws communities together, and when and why the same communities get driven apart? The 6 December demolition and the riots in its wake were but an aggravated moment in a drawn-out process that the novel is about. Seeing it as based on the Babri Masjid, besides being erroneous, would straitjacket the novel and direct attention away from its larger intrinsic potential.

And most importantly, my novel searches the contours of what in India is called secularist thought – a broad-minded plurality, where differences are respected, and equality is the ideal. Why did that thought lose its connection with the society and fail? The novel is concerned with this failure, this urgent need to look into our own selves, and try to understand where we have erred or weakened. Face ourselves, our dark deeps, and spot there the same prejudices we accuse the adversary of.

I would say my novel is about soul-searching and belongs to a larger time and span than one single event. That is what makes it resonate across borders.

Our tendency, particularly nowadays – when the political has so overtly intruded into the personal and the private – is to link all writing to a specific immediate. While indeed literature may resonate with a given immediate, it always transcends the immediate and the specific. It operates on a vaster canvas.

Sure, that moment in recent Indian history – the Ayodhya moment – is richly documented. But what literature seeks lies beyond, or submerged in, documentation.

Writing and literature is often seen as a radical act. In a country like India, where perceptions about religions are so dichotomous and, by extension, weaponized against each other, why is it important to turn to writing and literature as a political, radical act? Do you think fiction can radicalize people and should it?

One may, I can see, be tempted by certain disconcerting developments in recent decades to generalize that perceptions about religion in India are dichotomous and weaponized. These developments are, indeed, what brought Our City That Year into being. However – as the novel amply shows – there also has been a long living tradition of religious coexistence and interaction in this country. That tradition lives on. India is an organically pluralistic society. The statement about the dichotomization and weaponization of religions in India is untenable as a generalization.

It is significant that you mention writing as different from literature. Assuming that you mean by writing the broad spectrum of discursive and journalistic writings, much of it has admittedly succumbed to, even been infected by, the dichotomization and weaponization of religions in contemporary India. Those doing such writing, especially journalists, are more prone to close surveillance and ready reprisal. Literature, which does not deal with things in the same immediate and direct manner, is able to go on with its creative exposes!

Literature worth the name in all Indian languages has tended to be naturally human. It devises different ways to express itself. It has not had to be a professedly radical or political act to be a force for the good. Indeed, by and large, literature has naturally been that – a force for the good – across millennia and cultures.

I am ready to put it this way too. Literature, at any time, is a political act. It rearranges relationships, repositions perceptions, shifts borders, bringing the periphery to the centre, voices doubts, questions, and challenges assertions. It does not do so by running a court-case as it were, within the pages, but by giving space to amorphous, ambivalent, ambiguous ‘realties’. That is what transforms the reader and the writer. Inviting her to rethink, relook. Literature is always radicalizing.

Literature is always radicalizing. That is not in answer to your question: Do I think fiction can radicalize people and should it? Striking semantic reversals of recent times make it difficult for me to offer a straightforward answer. Radical till not long ago was a prized word, a virtue. Your own question about literature as a ‘political, radical act’ carries that valorizing connotation. Taking radical to denote refusal to compromise with injustice and exploitation, my answer would be ‘maybe’ and ‘yes.’ ‘Maybe’ to whether literature can radicalize people. ‘Yes’ to whether it should. However, ‘radicalize’ has acquired a dirty connotation to stand for bloodthirsty religious fundamentalism and terrorism. Taking ‘radicalize’ to mean that, the answer would be an unqualified ‘No.’

Congratulations on being the first Indian writer to win the International Booker Prize for Tomb of Sand in 2022! In what way, if any, has the recognition shifted the world’s view of regional Indian literature?

Thank you. It’s been just over two years since that happened. Not long enough to talk decisively about global shifts. In any case, one swallow doesn’t make a summer. Yet, the Prize has, in one dramatic moment, drawn attention to literature in South Asian languages. There is greater interest in translation. In the US itself, the SALT – South Asian Literature in Translation – project has come up to bring to the wide world more literature from these languages. What is important is to sustain this interest and help networks of publishers, funders, translators grow stronger. As of now the interest is visible but there could be greater support from the powerful, especially from established publishers and academic institutions.

Literature, at any time, is a political act. It rearranges relationships, repositions perceptions, shifts borders, bringing the periphery to the centre, voices doubts, questions, and challenges assertions.

In both Our City That Year and Tomb of Sand you turn to history to drive the narrative. History, as it is often said, is written by the victor, which is all the more true for events that are as divisive as the ones explored in your books. What does your research process look like? What is something surprising you learned while researching for Our City That Year?

Long years ago, I was a regular researcher and managed to earn a doctorate in history. But once I found my true calling, I turned my back on research. Our City That Year and Tomb of Sand are replete with history, but I did no academic research for either of them. Instead, many things came together that I had collected in my memory of personal testimonies and formal reports. I had also read much literature on Partition and Communalism. The history I remembered from my student and research days and, even more, the multiple, conflicting accounts that pass for history in popular remembrance were enough for the narrative requirements of both Our City That Year and Tomb of Sand.

That history tends to be written by victors is hardly a problem for those who know this to be the case. They read between the lines and against the grain, pulling out meanings and stories the victors’ history is designed to elide.

How has the reception from people differed between your books in Hindi and English? Did the translation bring in any new perspectives or readings you weren’t expecting?

All readers bring in new perspectives. But let us remember that the world has opened like never before and lovers of literature are reading books from various parts of the world. It is not as if the Hindi world is a closed world, limited only to Hindi writing. Almost everywhere, in fact, literary conversations are more global even if you work from within one language. No language or literature today operates in some closed hermetic space.

The readership of the books in Hindi would necessarily be confined to knowers of Hindi. With translations, particularly post-Booker, that readership has spread phenomenally in both the East and the West.

To mark India’s 75th year of independence, PEN America released a special project for which you contributed a poignant piece. In the preface to India at 75, we wrote, “In recent years, India has seen an acceleration of threats against free speech, academic freedom and digital rights, and an uptick in online trolling and harassment.” What does it mean to be a writer in today’s India?

Things in India are not as bad as all that. Nor as good as they should be. Not just in India but everywhere the Word today is feared, and silenced, more than it was till recently. While activists and journalists are watched – because of the palpability and immediacy of what their writing could do – fiction writers and their convoluted ways escape matching surveillance and retribution. Unless something happens to bring someone under the radar. But, like they have always done, writers will write in all times, devising appropriate strategies.

In India, too, one navigates and negotiates one’s space, and you will be surprised how much is written and spoken even in these difficult times. And how subversive some of that is. Imagination and Creativity are untrammeled and untamed beasts!

All writing is translation. To write is to translate that which is inarticulate inside you.

What is your advice to young writers and translators, especially those working in regional Indian languages?

All writing is translation. To write is to translate that which is inarticulate inside you. To translate is to write in a different language that is already there in another language. I am not a translator, but I can sense the equivalence. Young translators should take no less pride in their work than do writers in theirs. And devote to their work the passion and hard work that any creative endeavor calls for.

To those working in their own mother tongues in India, the land of multiple languages with long rich lineages and literatures, I would say: Value that you come from one such language and stand firmly on that ground. From there go as far and as high and as different as you desire! Bring your native periphery as much to the center as you can.

Geetanjali Shree is the author of five novels, including Tomb of Sand for which she was awarded the 2022 International Booker Prize, and five story collections. Her work has been translated into several European and Asian languages, and has received numerous accolades. She lives in New Delhi, India.