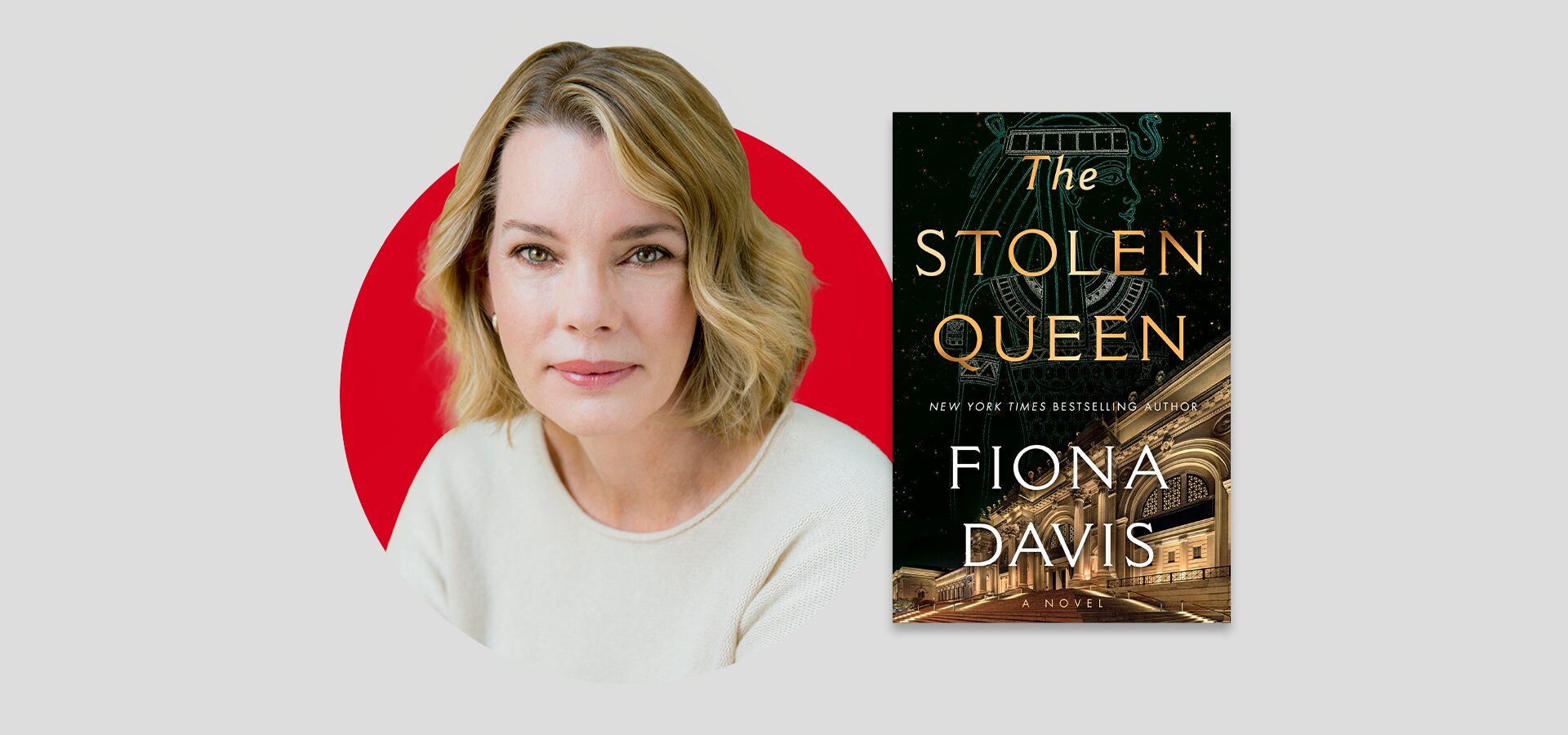

In her eighth novel, The Stolen Queen (Dutton, 2025), New York Times Bestselling author Fiona Davis brings together a startling theft and wayward women in a tale that jumps through time. The interweaving narratives of the toiling Vogue employee Annie Jenkins and Metropolitan Museum of Art Associate Curator, Charlotte Cross, recount a chaotic evening at the Met Gala when a prized artifact, the Cerulean Queen, is stolen. Thrown together, Annie and Charlotte set out to solve that mystery and others in a journey that will change their lives forever.

In conversation with PEN America’s Membership Engagement Manager, Aleah Gatto, for this week’s PEN Ten, Davis shares how her background as journalist shapes her research process for historical fiction, the cultural conversation around the repatriation of art works, and her exploration of the perception and treatment of women across civilizations and millennia. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble).

The story of The Stolen Queen involves several subjects that necessitate research: ancient Egypt, archaeology, 1970’s fashion, the inner workings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. How did your background in journalism prepare you for the research that was necessary for this book?

The first day of journalism school at Columbia, we were told to go out and interview strangers on the street, write a story, and turn it in by the end of the day. I was new to the field of writing and reporting, unlike some of the other students who had more experienced, and I was terrified. But eventually it became second nature to locate experts in whatever subject I was writing about, pepper them with questions, and create a narrative with the information I’d gleaned. That’s helped enormously in terms of writing fiction that requires a lot of research. Once I decided that the plot of The Stolen Queen would involve the Met’s Egyptian Art Collection, as well as the Costume Institute’s Met Gala, both circa 1978, I wasn’t afraid to reach out to “experts”–curators, technicians, conservators, security guards, as well as staffers at the Costume Institute–and dig into the details of what’s involved with those particular jobs and how those departments operate. One tip I learned at j-school that helps me to this day is to be particularly tuned in to what’s brought up at the end of an interview, as you’re wrapping up. That’s often when an idea or nugget of pure gold arises. You just have to be ready for it.

How do you think the story, whose plot is driven by the notion of reexamining history, fits into the larger conversation about the museum industry, particularly when museums acquire and showcase unethically sourced art and artifacts?

The question of the repatriation of stolen art has been going on for a long time, but it feels like it’s very much in the news these days. Every major museum—not only the Met—is reexamining its collection and assessing what antiquities should be returned to the country of origin. In New York City, there’s even a special unit in the police department that tracks down and returns stolen antiquities from private buyers and museums. But what happens if the country of origin doesn’t have the facilities to safely store the antiquities? What if, for financial reasons, the government decides to sell an artifact to a billionaire who then locks it away in his mansion, out of the purview of scholars and researchers? Do the artworks belong to all of humanity or to a particular country? While there are no easy answers, I felt compelled to explore these questions in the book through the point of view of the character of Charlotte, an associate curator at the Met who’s forced to reevaluate everything she thinks she knows on the subject over the course of the story.

What happens if the country of origin doesn’t have the facilities to safely store the antiquities? What if, for financial reasons, the government decides to sell an artifact to a billionaire who then locks it away in his mansion, out of the purview of scholars and researchers? Do the artworks belong to all of humanity or to a particular country?

You invent an Egyptian-based terrorist organization, Ma’at, that is suspected to be behind the theft of the Cerulean Queen—a prized artifact at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. How did you conceive of this organization? How do you think the role it plays in the novel will translate to readers?

Ma’at in Arabic is the goddess of truth, justice, balance, and order, so the name fit for a group that’s determined to right what they consider the wrongs of the past. By inventing a secret Egyptian organization and having them “take back” the Cerulean Queen, I could explore the assumptions and principles surrounding repatriation, as well as broaden the mystery of the missing statue in the story. The members of Ma’at believe that order can only be restored by returning the objects to their home country by whatever means necessary, and that theme is echoed in the (also invented) curse of the pharaoh Hathorkare, which states that anyone who takes an object dear to Hathorkare out of Egypt risks the wrath of the gods. While Ma’at’s methods are suspect, I hope readers will see what a passionate and universal subject repatriation is.

You’ve noted how your inspiration for Hathorkare—the female pharaoh whose role in ancient Egypt was altered by her male successor and heedlessly overlooked by modern archaeologists—came from the tragic story of Hatshepsut. What sparked your interest in Hatshepsut?

I’m always interested in how women’s voices and agency have changed over time. After learning about the rare female pharaoh Hatshepsut—who was depicted by Met curators in the 1950s as a “vain, unscrupulous, and ambitious woman”—I knew the lingering questions surrounding her legacy with would resonate with the character of Charlotte, whose contributions have been also suppressed. Hatshepsut ruled successfully as regent for twenty years before her stepson took over, and brought peace and economic prosperity to Egypt. Yet after her death, the new pharaoh ordered many of her images hacked and her statues destroyed. The question of why he did so, and when exactly that occurred, becomes something of an obsession for Charlotte. In that way, the title of the novel refers to both the antiquity that’s stolen in the story, as well as the almost-lost legacies of Hathorkare and Charlotte.

From the very beginning, I was determined to throw together two very different women in terms of age, temperament, status, and background in the hunt for the missing statue and see what transpired.

One of the main themes of the story concerns relationships between women: mother-daughter, young-old, modern-historical. The two main characters, Charlotte and Annie, come to represent each of these relationships as their lives intertwine. Why did you use this theme as a focal point of the story?

I knew from the very beginning that I wanted to explore mother/daughter relationships, and by extension mentee/mentor relationships, like the one Annie develops with Diana Vreeland and later, Charlotte. Annie’s relationship with her own mother is one that’s reversed, in that she’s the typical “parentified child,” and I liked the idea of her seeking out older women in positions of power to learn how to overcome her insecurities, how to stand on her own two feet. In the beginning of the story, Annie is over-invested in her mother’s well-being, and then does the same in her new job as Vreeland’s assistant, because her identity is tied up in what others think of her instead of what she thinks of herself. I really loved writing from Annie’s point of view, charting her progression from frightened child to a woman who finally knows and trusts her own mind. For Charlotte, the forced partnership with Annie evolves into a second chance to explore her motherly instincts, even if that’s the last thing she wants to do. From the very beginning, I was determined to throw together two very different women in terms of age, temperament, status, and background in the hunt for the missing statue and see what transpired.

One dilemma that recurs throughout the novel is that of women being undermined across centuries, seas, and professions. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the parallels between how women were treated in the Egypt of antiquity and in the United States today. What similarities do you see? What differences?

It’s fascinating to compare ancient and modern times when it comes to the treatment of women. What surprised me about women’s rights in ancient Egypt is that they were in many ways far more advanced than those of American women in 1978, when the book opens. Ancient Egyptian women had the right to get divorced and the right to own property, and having children out of wedlock was perfectly acceptable. When you consider that in America, until the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 was passed, a woman couldn’t get approved for a credit card without a man co-signing the application, we seem to have backtracked a great deal.

Some characters in The Stolen Queen are inspired by—or are fictionalized versions of—real people: Hathorkare came from Hatshepsut, Charlotte Cross from the archaeologist Elizabeth Thomas, who was the first to reexamine Hatshepsut’s history. When we meet Diana Vreeland, the famed fashion writer and special consultant at the Met’s Costume Institute, character and real person become indistinguishable. How did you decide when to write fictionalized or real versions of your characters?

There are so many real people who inspired my fictional characters, including the pharaoh Hatshepsut, Egyptologists Elizabeth Thomas and Christiane Deroches Noblecourt, and scholar Charles Nims. In terms of Hatshepsut, I wanted to include my character Charlotte in the rehabilitation of the pharaoh’s legacy as well as the discovery of her mummy in the plot, but that required compressing the timeline of those events and ousting the actual scholars and archaeologists who did all the hard work. By creating a fictional female pharaoh named Hathorkare, I gave myself some freedom in terms of the timeline and who-did-what-when so the plot could flow seamlessly and logically. In every book, I make it clear in the author’s note what’s based on fact and what was made up, and share my resources so readers can fall down the same rabbit holes I did while researching. In terms of keeping Diana Vreeland in the storyline, the woman was such a force of nature, so iconic, so over-the-top, that any fictional character would fade in comparison. She really is irreplaceable. And because Vreeland in fact was the special consultant for the Met Gala in 1978 and oversaw the Costume Institute’s exhibition and gala–as she does in the novel–I felt confident keeping her in the story as is.

It’s fascinating to compare ancient and modern times when it comes to the treatment of women. What surprised me about women’s rights in ancient Egypt is that they were in many ways far more advanced than those of American women in 1978, when the book opens.

The slew of mysteries that build throughout the story meet twists that give way to satisfying ends. What did the storyboard look like for this novel? Did you know how each mystery would conclude, or did the solutions develop as you wrote?

I tend to plot out my books beforehand, and that was a definite requirement with The Stolen Queen, as I knew the first half would involve two timelines and three points of view, which would then converge into a linear timeline with two points of view. The structure was complex in terms of voices and how and when to reveal clues to the mystery of who stole the antiquity, when to drop red herrings, as well as figuring out the ideal moment to reveal the truth regarding the suffering that Charlotte experienced in Egypt as a young college student. I plotted each timeline separately, and then, in the second half, figured out which character’s point of view worked best for which scenes. Even then, the novel changed greatly over the course of ten revisions. Chapters were reordered, part of the ending was completely reworked, and eventually everything fell into place. I was lucky to have editors and author friends who helped whack it into shape, as The Stolen Queen required more structural changes during the revision process than any of my other novels. But, in the end, it was a satisfying puzzle to put together.

Part of the novel takes place in the 1930’s, and part in the 1970’s. If the events from either time period took place today (an archaeologist getting stripped of her rank and dignity due to an unexpected pregnancy, an artifact stolen from the Met, a young woman finding herself at the mercy of a formidable cultural institution), how do you think they’d differ? How would they be the same?

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 made it illegal to discriminate against an employee for being pregnant, so the 1930s archaeologist would have legal standing to sue and collect damages, a concept that would have been completely foreign at a time when female archaeologists were still a rarity. If the theft at the Met occurred today, it would be quite difficult to pull off with the plethora of security cameras in every gallery and hallway. The cameras weren’t installed until the late 1980s, which, lucky for me, made the 1978 theft in the book plausible. As for Annie’s persecution by the Met’s staff after the theft, I imagine it would be even worse today. She single-handedly ruins the “party of the year,” and no doubt the crisis would go viral on social media, turning poor Annie into a laughingstock/suspect. I don’t think she could have survived that.

Is there a specific audience that you hope to reach with the story? If so, is there a particular message that you hope will come across?

The book is written for a wide audience, but I do think women will be drawn to the themes of female friendship and mother/daughter relationships. Ultimately, the story explores the importance of reclaiming women’s contributions to history, whether by an ancient pharaoh or a modern-day curator. I also hope the book offers up a different way of looking at a grand institution like the Met Museum—not as a collection of art, but a collection of stories—and how by examining the stories behind the objects, we get a richer sense of the times and places of the past.

Fiona Davis is the New York Times bestselling author of several novels, including The Spectacular, The Magnolia Palace, and The Lions of Fifth Avenue, which was a Good Morning America book club pick. She’s a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School and is based in New York City.