Sign the petition for the release of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo »

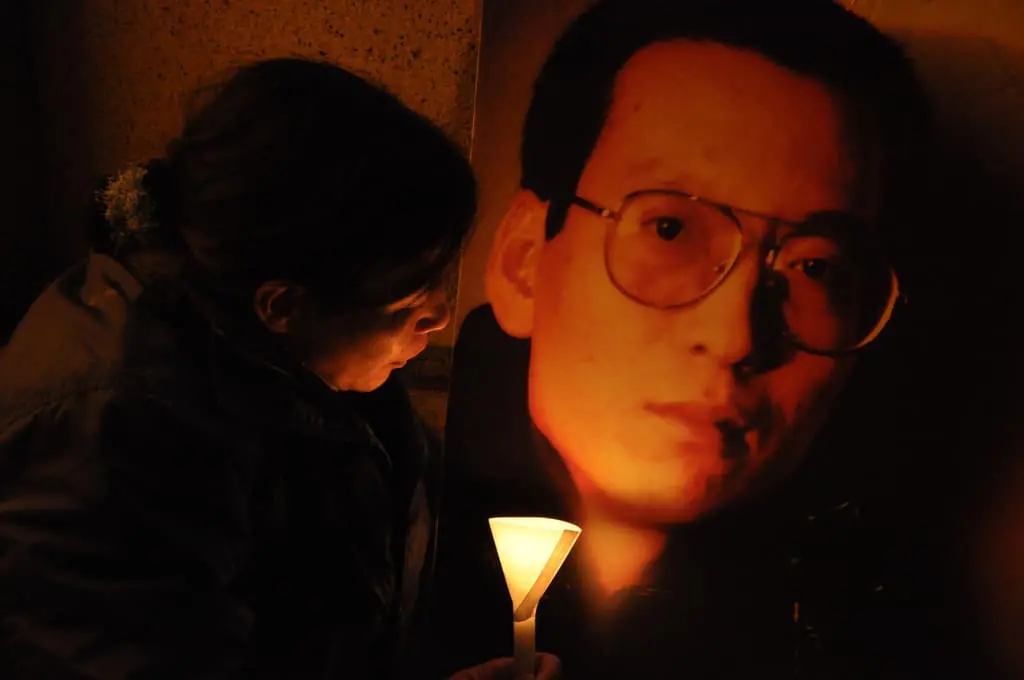

At nine o’clock at night on December 12, 2017, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo (also known as Moe Aung), both Myanmar reporters for the Reuters news agency, were arrested after a meeting with police in Yangon. After being detained in Myanmar’s infamous Insein Prison and kept from seeing their families and lawyers for 11 days, almost a month later they were formally charged with violating the Official Secrets Act by allegedly obtaining information related to a military campaign in Rakhine State illegally. The journalists remain in prison as they await their next hearing on February 6; their application for bail has been denied. If convicted, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo face up to 14 years in prison.

At the time of their arrest, the reporters were in the midst of working on a sensitive investigative story, and their dinner meeting with police appears to have been a carefully orchestrated setup: They were handed official documents at the meeting and then detained shortly thereafter, and permission for the charges to go ahead was speedily granted that very night by the president’s office, according to testimony offered at the January 23 court hearing. The 1923 Official Secrets Act under which the journalists were charged is a little-used law created during the British colonial period that punishes those who have the intention of sharing anything the government wishes to hide. Win Htein, a spokesperson for the ruling National League for Democracy party, claimed it was likely that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were “caught in a trap.” The journalists told their family members that they were arrested almost immediately after they were given unidentified documents related to the abuses occurring in Rakhine State by two policemen who had invited them to dinner. The manner in which the journalists were arrested may be a powerful indication of the great lengths the military is taking to bury the realities of military action against the Rohingya Muslims, a long-persecuted and generally stateless minority.

The abuses that Myanmar’s security officials are accused of is an international concern of the highest order. Since August 2017, following attacks on police posts by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) insurgent group, a Myanmar military campaign has resulted in approximately 700,000 Rohingya Muslim civilians fleeing Rakhine State in western Myanmar for neighboring Bangladesh. The United Nations has described the military’s campaign—including numerous acts of murder, rape, and arson—against the Rohingya as ethnic cleansing. Myanmar denies this definition and has rejected almost all of the allegations, criticizing human rights groups, the United Nations, and international media organizations for their coverage of the Rohingya crisis. Upsetting realities are described as “fake news” and the integrity of reliable news sources such as the AP and BBC are attacked. Meanwhile, access to Rakhine State is now firmly controlled by the military. The Myanmar government refuses to allow United Nations investigators and international media outlets into Rakhine, which makes reporting on the atrocities extremely difficult.

Despite these restrictions, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were attempting to cover these stories for Reuters and to shed light on the alleged mass atrocity crimes in Rakhine State. In a statement made on January 10, 2018, the date the journalists were formally charged, the Myanmar military admitted that security forces and villagers captured and killed 10 “Bengali terrorists” and buried them in a mass grave in the village of Inn Dinn in Maungdaw Township. The two Reuters journalists had been investigating that same grave. That their reporting may have helped pressure the army into this admission only further suggests that the two journalists were arrested for uncovering a tragic secret the military intended to keep hidden.

The arrest and prosecution of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo is especially troubling as it also represents another nail in the coffin of Myanmar’s brief flowering of broader press freedom and freedom of expression, considered essential to the country’s possible transition into a successful democracy. The news media, once heavily restricted during military rule, experienced a rebirth from 2011–2014 during a period of transition from military to quasi-civilian rule. During those years dozens of new media outlets (some of which returned to the country after having long operated in exile) pushed through what once was a heavy veil of censorship. Myanmar’s government is now accused of cracking down on the media, contradicting its ostensible commitment to the democratic principles once supported by the National League for Democracy, which assumed power in 2016 after historic elections in November 2015. Since the party claimed power in 2016, there have been at least 32 journalists charged with crimes. Dozens of cases have been filed against ordinary citizens as well, many for online defamation under Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Act, which criminalizes broad categories of online speech.

Journalists like Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who attempt to report on sensitive subjects, are particularly at risk of harassment or legal repercussions for their work. Despite their incarceration, the reporters refuse to be silenced. After the court hearing on January 10, 2018, Kyaw Soe Oo told other journalists, who had come out to show support, “We are not doing anything wrong. Please help us by uncovering the truth.”

Sign the petition for the release of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo »