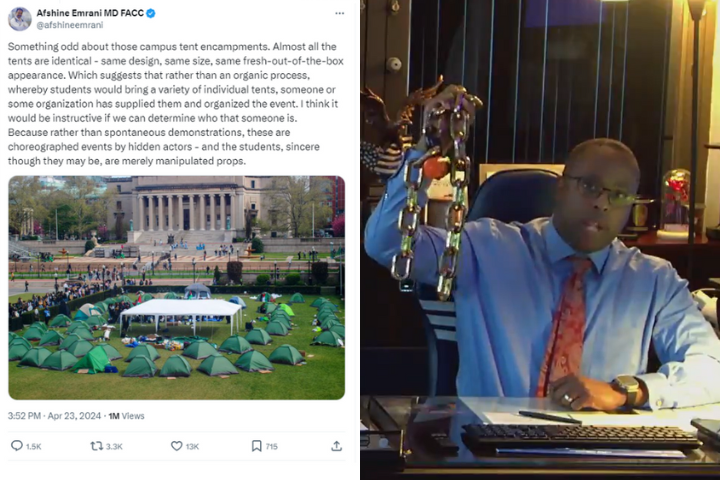

Students at Columbia University erected their ‘Gaza solidarity encampment’ in April, and within a month more than 200 campuses in 25 countries and 45 states had followed suit.

To those familiar with the campus upheavals of the 1960s, history seemed to be repeating itself. And yet there are key differences between the protests then and now, according to Emerson Sykes, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, and Dr. Gregory Wilson, distinguished professor of history at the University of Akron.

Last month, PEN America and the University of California’s National Center for Free Speech and Civic Engagement jointly hosted a webinar titled “Campus Protests Then and Now,” moderated by Dr. Spoma Jovanovic, professor emerita at the department of Communication Studies at UNC Greensboro. Together with Jovanovic, Sykes and Wilson delved into popular disinformation tactics, the rights of student protestors, and their recommendations for college and university leaders.

The Legacy of Kent State

To open the webinar, Wilson described protests that broke out on May 1, 1970 in response to former President Richard Nixon’s announcement that the U.S. military had invaded Cambodia. At Kent State University, a few hundred students held a demonstration and decided they would rally together on May 4. However, violence soon broke out in downtown Kent, and rumors began circulating that outside instigators were attempting to bomb and destroy the town. The mayor of Kent then called in the National Guard, which sent members to Kent State despite the fact that university officials did not request their presence on campus.

In the coming days, the National Guard used tear gas and bayonets to disperse groups of students and force them back into their dormitories. On the day of the rally, guard members fired 67 shots in 13 seconds into a crowd, killing four students and wounding nine others. The event galvanized student resistance nationwide: “Four million students went on strike [and] shut universities down across the country in the wake of the Kent State shootings,” Wilson said.

Wilson highlighted a few differences between the protests at Kent State and Gaza solidarity encampments, including the shifting landscape of higher education.

“We’re seeing a tax on higher education generally, cutting back of programs — all of these different things that question the value of education and really democracy too,” he said. “Those stakes are different than what we had in the ’60s and early ’70s.”

‘Outside Agitators’ Then and Now

He also noted the reemergence of the claims that “outside agitators” rather than community members were primarily at fault. “It’s a politically-charged term that has a little bit of truth, but not much,” he said, touching on the presence of such claims not only at Kent State but also throughout the Civil Rights Movement and during the Cold War, as the national organization Students for a Democratic Society gained popularity.

“The dissent, whether it was civil disobedience, or peaceful protest, or whatever it might be, was generated by students at the campus, for the most part,” Wilson said. “It’s then used — the term ‘outside agitator’ — often as an excuse to use some kind of excessive force…against a group of students.”

Restrictions and Civil Disobedience

Sykes emphasized that although universities can intervene in protests, it is unnecessary for them to take draconian measures against their students. PEN America and the ACLU have said that the police should be an absolute last resort, called in only when there is a real threat to security.

He clarified that the government, which includes public colleges and universities, cannot restrict protests because of their content, but they can place content-neutral restrictions on their time, manner, and place, and as such, many encampments are not protected speech under the First Amendment. “Many of the protestors who are engaging in these things know full well they are breaking the rules and are expecting to suffer the consequences — which is the definition of civil disobedience,” he said.

Social Media and Surveillance

Both panelists also addressed the role of social media and increased surveillance in the protests. Wilson said that social media has the ability to accelerate demonstrations in unprecedented ways, and Sykes agreed, adding that there are now increased opportunities and risks. Social media allows for solidarity and the rapid spread of information — but also presents the danger of doxxing and misinformation.

Educating vs. Punishing

Additionally, Sykes clarified the boundary between the First Amendment and anti-discrimination laws, explaining that even offensive speech is protected unless it creates a hostile educational environment under Title VI. He urged universities to address harmful behavior, however, regardless of whether it is technically constitutionally protected.

“There has to be space for a university to say, ‘Listen, what you said may not be unprotected speech, and it may not have even created a hostile educational environment, but we are here to help you learn and grow, and therefore we’re going to address this conduct,’” he said. “In all of this talk about constitutional lines…what often gets lost is all of the ways in which a campus community can and must respond and heal in response to these really difficult times.”