Navigating Disinformation as a Student Journalist

By Elizabeth Lepro

Student journalists are in a community reporting sweet spot.

They are privy to insight from their university’s administration and the student body it serves – one ear to the ground for news on campus, another tuned into the administration for budget updates, tuition increases, and other developments that affect students and professors.

Beyond that, student journalists are watching for news in the communities and cities that surround their campuses. As local news outlets fold across the country, student journalism is playing an increasingly vital role in local coverage.

Events on college campuses can also become national news. When the organizing efforts of unions representing graduate students are noticed by national publications, for instance, that’s good news for the unions. But when activities on campus are misreported or distorted by national news outlets – as was the case in the Oberlin College campus dining hall controversy – that’s not so good, for anyone.

Student journalists can’t keep national outlets from reporting based on their own agendas, but they can take concrete steps to counter false narratives early and bring more accurate news to their communities.

The benefits of pre-bunking

There’s a word for taking steps to guard against manipulation of the media: “pre-bunking,” which means “to preemptively refute expected false narratives, misinformation or manipulation techniques,” journalist Seth Smalley reported for Poynter. “As opposed to fact-checking every instance of a false claim, which many argue is impossible, prebunking seeks to inoculate the public against anticipated narratives in advance.”

Pre-bunking isn’t a cure-all when it comes to reporting on disinformation (there is no cure-all), but it is one way to tackle the problem, with roots in community engagement.

A primary reason that disinformation-focused organizations like First Draft News have recommended pre-bunking as an alternative to solely debunking is because of how information travels: It’s difficult to correct a false narrative once it’s gained traction. Plus, once a critical mass of people believe something, efforts to counter the narrative can be painted as silencing tactics, further reinforcing the original belief.

How can student journalists use pre-bunking techniques to find and fight false narratives in their communities? Here are a few ideas.

Find the participatory communities

As First Draft News has pointed out, people who seek to spread disinformation do so by engaging in organic, participatory networks, typically on social media.

QAnon, for example, began in 2017 as a few innocuous posts in a 4Chan forum. Over time, more people were drawn in. Eventually, QAnon became a game. Not only were more people buying into every post, they were encouraged to engage with threads, participate in guessing games, and look for clues in then-President Donald Trump’s speeches and social posts.

By contrast, efforts to expose conspiracy theories like QAnon often come from media institutions, which can seem less relatable to some audiences, and therefore harder to connect with. For some, it may feel like a choice between trusting your neighbor or friend over a faceless institution.

“Effective disinformation communities are participatory and networked, while quality information distribution mechanisms remain stubbornly elitist, linear and top-down,” wrote Carlotta Dotto, Rory Smith, and Chris Looft for First Draft News.

The good news is journalists can find and engage in participatory communities, too. The immigrant-focused news outlet Documented, for instance, uses WhatsApp to receive and broadcast information that pertains to New York City’s immigrant community. The University of Pittsburgh’s student newspaper, The Pitt News, publishes a yearly special edition called Silhouettes in which it invites students and faculty to submit ideas for interesting people around campus to profile.

Because Documented knows its audience, it is able to get scoops on scams, disinformation, and conspiracy theories in early circulation.

Here’s how you can start identifying participatory communities:

- Editors: Talk as a newsroom about your community. Use what you know. What kind of hot-button issues are prominent at your university? What kind of topics draw large emotional responses on campus? Prepare in advance how you’ll report on these issues.

- Reporters: Be conscientious about being in the same spaces as your audience. What social media channels can you be on? Where is information being shared informally? How can you create space in these channels for engagement?

- Reporters and editors: Join and follow social channels like Facebook groups, TikTok trending topics on campus, WhatsApp groups, Reddit, and Discord.

Break out of your algorithm

If you’re using social media to find story leads, you may be missing out because the algorithm that determines what you see is tailored to you. This creates a filter bubble, a term credited to Eli Pariser, who wrote a book by the same name.

Some journalists make significant efforts to figure out what people are exposed to online. The BBC’s Marianna Spring used five cell phones to create five online personas to better understand what U.S. voters are exposed to, based on their political beliefs.

You may not have the time or resources to go that far, but you can adopt the idea. Consider using a social monitoring tool like Hootsuite to create a dashboard to see what’s happening across platforms.

Social listening, the practice of monitoring online conversations, can help you see how a rumor rises from online speculation to the level of public misinformation.

As you’re researching, remember to keep your own ethical considerations in mind and avoid using tools that exploit people’s personal data. This Medium post from Tom Trewinnard dives into the paradox of social media monitoring tools, which can be as nefarious as they are useful to journalists and researchers.

Know your search terms, test your theories

Once you’ve found participatory communities, broken out of your algorithm, and brainstormed as a newsroom what kind of dis- or misinformation is likely to circulate on your campus, you’ll want to keep an eye on topics of interest to your audience.

You can learn to use Boolean operators for more targeted searches. The basic Boolean operators are “OR,” “AND” and “NOT,” along with parentheses and quotation marks. Using “OR” allows you to search for two separate words or phrases at once, while “AND” will bring up only search results that include both words/phrases you’re looking for. For example, use “college students” AND voting AND Ohio if you want information about college voting behavior in that state.

You can also set Google alerts based on Boolean terms to receive automatic updates on phrases you’re following. Check out this article from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for more information on Boolean operators.

One way to check whether the search terms you’re following are gaining traction is by using the Google Trends Explore feature.

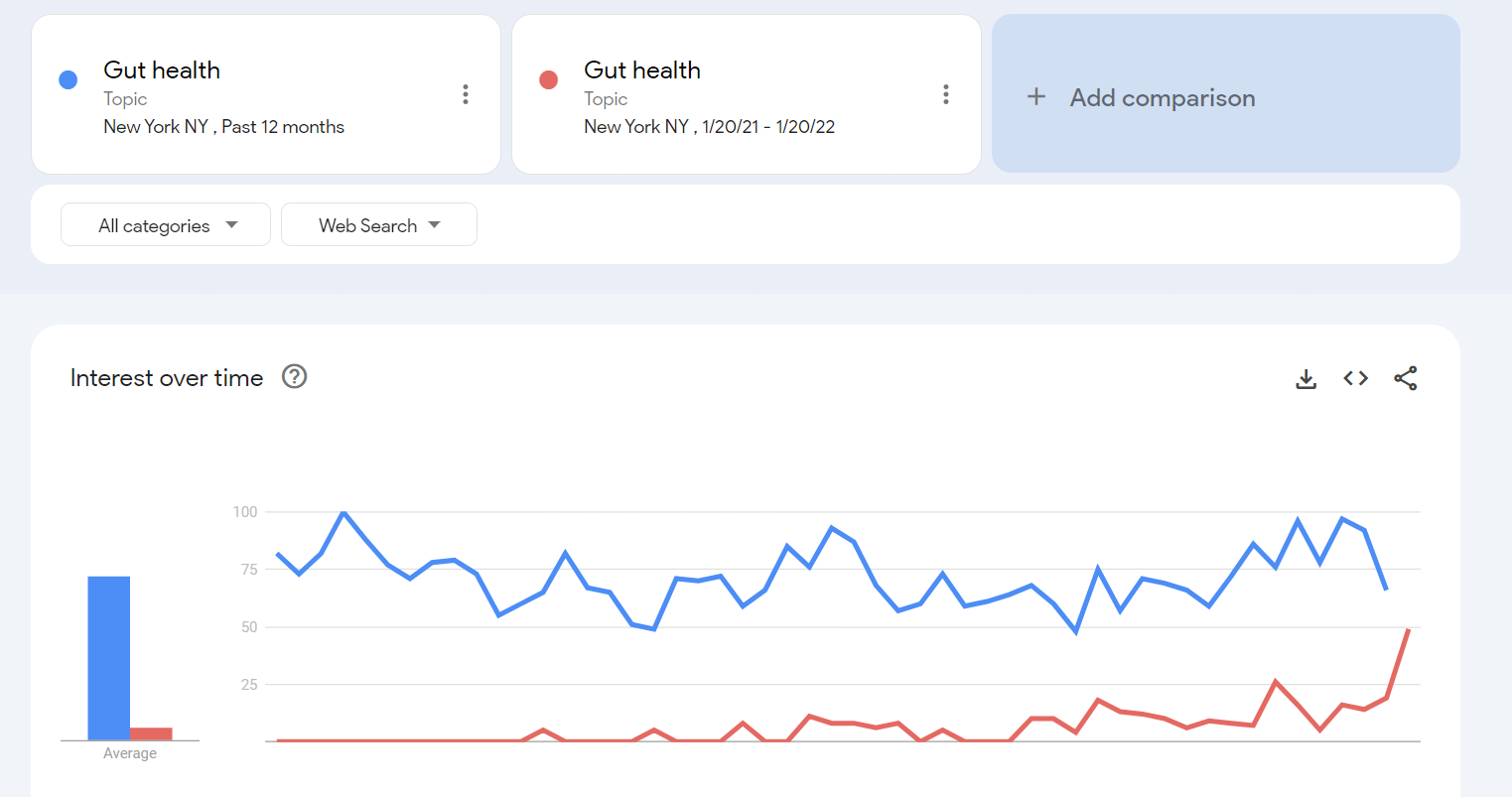

For example, if you’re seeing a lot of students on social media talking about gut health–a wellness trend that’s rife with misinformation and unregulated supplement advertising–you can test your theory that it’s gaining popularity by comparing data for the term “gut health” now compared to previous years.

Google Trends won’t provide enough evidence to base an entire story around, but it’s one way to confirm that a topic is attracting attention and possibly worth investigating more.

Take what you’ve learned to your community

Once you’ve begun reporting on mis- and disinformation on campus, begin thinking about how you can most effectively disseminate accurate reporting in your community.

It’s hard for writers to admit, but sometimes a story isn’t enough–or, it isn’t the only way to reach audiences. Community-centered journalism opens up more avenues for storytelling.

- Try creating an explainer around a myth-prone topic, like this public service guide on the COVID-19 booster shot from investigative outlet PublicSource

- Experiment with other mediums, like these students at Murray State University, who embedded audio explainers into their stories, via Trusting News

- Hold in-person events, like round tables, workshops, or community meetings

- Consider partnering with civic institutions in your neighborhood focused on the same issues to offer collaborative resources or events and reach more people

For more information on how PEN America is using community engagement tactics to create disinformation resilience, check out this article.

No single tool, tip, or technique is going to help you counter disinformation from your college newsroom on its own. But equipping yourself with a variety of resources, working collaboratively as a newsroom, and preparing in advance will help immensely.

The most tried-and-true methods for countering disinformation are those you already know how to do: get out in the community, talk to people, cross-check your research, and keep up with important sources. In other words, be a journalist!