Saad Mohseni | The PEN Ten Interview

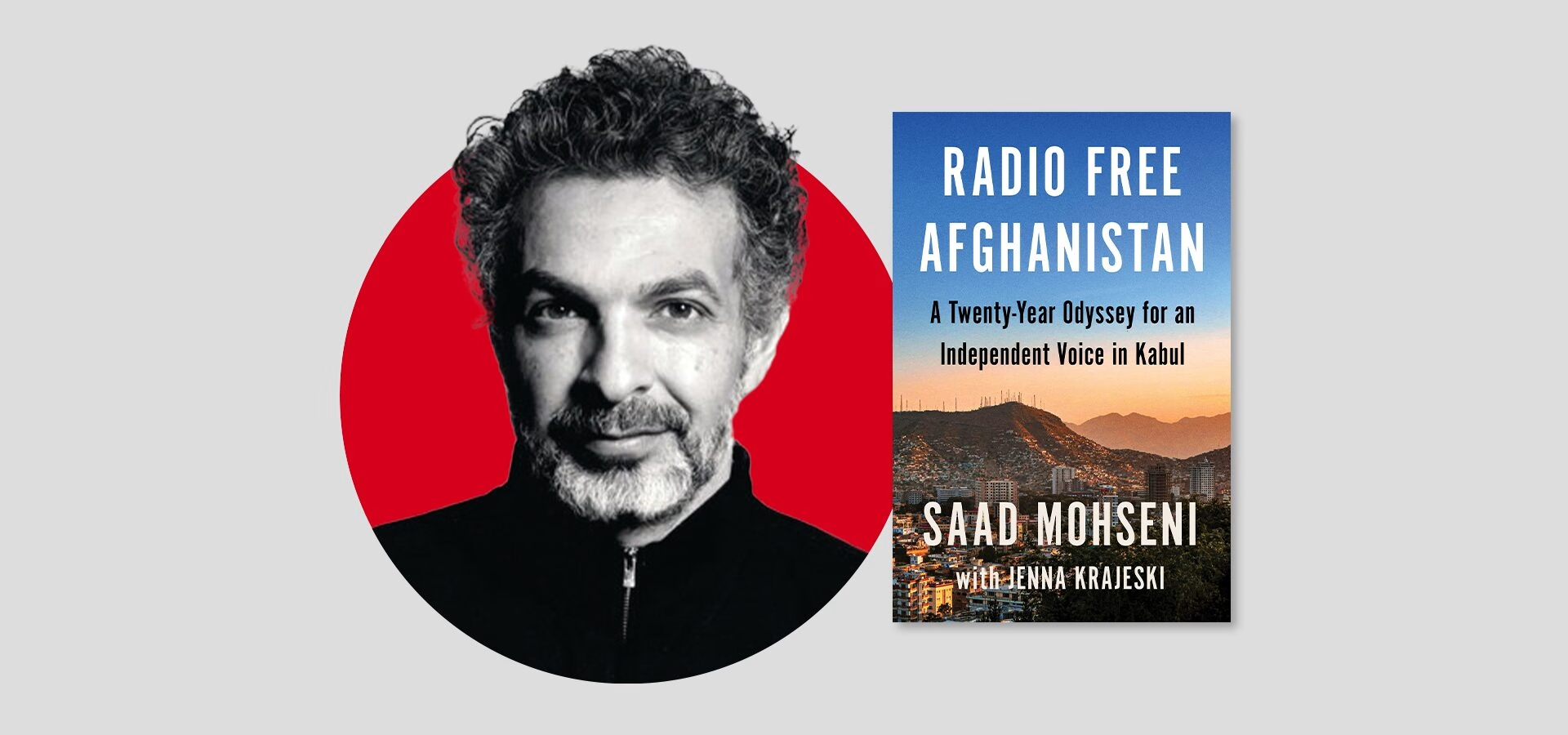

Saad Mohseni, CEO of MOBY Media Group, left a career in international banking to start a local radio station in Kabul with his three siblings. In his autobiography Radio Free Afghanistan (Harper, 2024), co-written with Jenna Krajeski, he describes how the station unexpectedly blossomed into a television empire, becoming an outlet, resource, and beacon for millions of Afghans.

Capturing the hope and resilience of the Afghan people, Mohseni says writing the memoir was “almost cathartic,” and that through writing it, “I realized that we must continue. Afghanistan is far from lost.” In conversation with Artists at Risk Connection’s Communications and Editorial Assistant Valentine Sargent, Mohseni offers his insights on speaking truth to power, the importance of keeping audiences engaged, and providing a platform for free expression across a diverse population. (Bookshop, Barnes & Noble)

1. You write about your experience hiring aspiring media workers who had to learn journalistic ethics and how to remain unbiased in their reporting. Later, MOBY media workers had to navigate the difficult terrain of rules and regulations imposed by the government and later the Taliban. What is the responsibility that comes with free expression, especially when considering Afghanistan’s diverse population?

Ultimately, we have three core responsibilities as the primary news provider for a nation of 40 million: a) to inform and educate, b) to foster debate on critical issues, and c) to hold institutions and individuals accountable.

The Taliban’s intolerance for any form of dissent makes our job particularly challenging. However, over the past three years, we have successfully created the space necessary to fulfill these objectives.

The Afghan public is increasingly bombarded with fake or inaccurate news. Our reporters frequently act as fact-checkers, distinguishing myths from facts.

2. You describe several instances throughout the years in which MOBY’s programming was disrupted by religious rioters, corrupt government officials, or the Taliban’s violence. Now that MOBY has expanded to South & Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa, what do you perceive to be the biggest threats to free media today?

Media operators today face a fragmented and highly competitive market.

In Afghanistan, we confront the typical commercial challenges while also navigating a restrictive environment where authorities are uneasy with the existence of an independent media group. When it comes to news, we fight to report every story. Additionally, we are engaged in an ongoing battle against the flood of fake news that continues to spread across the region.

The fear never entirely disappears; in fact, it is crucial to acknowledge this fear as it helps us mitigate some of the risks we face.

3. There is a lot of fear associated with reporting on people in power, especially those who choose violent ends. What is your relationship between fear, accountability, and justice?

While we remain committed to speaking truth to power and holding institutions and individuals accountable, we must also prioritize the safety of our journalists and employees.

The key is to balance these conflicting challenges on a daily basis.

The fear never entirely disappears; in fact, it is crucial to acknowledge this fear as it helps us mitigate some of the risks we face.

4. You describe how Afghans need soap operas just as much as the news. Why do you think people need a diverse range of stories?

We view ourselves, first and foremost, as storytellers. Ultimately, our goal is to entertain, inform, and educate our audiences. Scripted series—whether drama or comedy—and reality shows keep audiences engaged, providing millions with much-needed relief.

5. You detail Moby reporters interviewing the Taliban, the government, and citizens with the same air time. How did you ensure empathy was central to Moby’s reporting?

Maintaining a balance between the Taliban’s narrative and that of the ruling authorities was perhaps one of the most challenging tightrope acts our team faced during the republic days. In some instances our colleagues and the station, etc., were investigated for national security crimes because we chose to interview Taliban commanders and reported on their activities.

However, we were better able to address many issues by delving into the factors that contributed to the Taliban’s rise. These included corruption, nepotism, civilian deaths at the hands of Afghan and U.S. forces, predatory behavior by the state, and more.

Authority and responsibility go hand in hand, and many of our journalists operate as self-contained units capable of producing world-class news stories and documentaries.

6. What are the similarities and differences between Western and Eastern media? What can Western media learn from Eastern media outlets, such as Moby?

It is very difficult to generalize about “eastern media.” To this day, Afghanistan remains freer than many outlets in Turkey and India. I am referring specifically to news output, not the dress code of our female employees, who are required to cover up.

I believe we succeeded in recruiting and training an extraordinary group of Afghans who are then empowered to take initiative. Authority and responsibility go hand in hand, and many of our journalists operate as self-contained units capable of producing world-class news stories and documentaries.

7. How can media workers repress extremist movements?

Media workers have a responsibility to help their audiences understand radicalization by investigating the underlying conditions that contribute to it. It is important for the outlet or reporter not to judge but to seek to understand the factors that have contributed to this mindset.

8. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

I have come to understand that, in some ways, everything passes, and the crisis facing Afghanistan will also pass.

9. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

Afghanistan—its land, people, and history—continues to move me and compels me to keep going. I am inspired by the courage of our employees, particularly our female reporters and producers.

I have come to understand that, in some ways, everything passes, and the crisis facing Afghanistan will also pass.

10. Your book rejects the notion that Afghans are deprived of hope. How do you remain hopeful about the future of Afghanistan?

Is there any option other than to remain hopeful?

Saad Mohseni was born in London to Afghan parents in 1966 and lived in Japan, Australia, Uzbekistan, and Pakistan before returning to Kabul in 2002 after the U.S. invasion. He is the co-founder, chairman, and executive officer of Moby Group, Afghanistan’s largest media company and has brought top-tier news and media content to emerging markets for the past two decades. He was named an Asia Game Changer by the Asian Society and in 2011 was one of Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People in the World.” Mohseni serves on board of the International Crisis Group and is a member of the International Advisor Council for the Middle East Institute. He lives in London and Dubai.