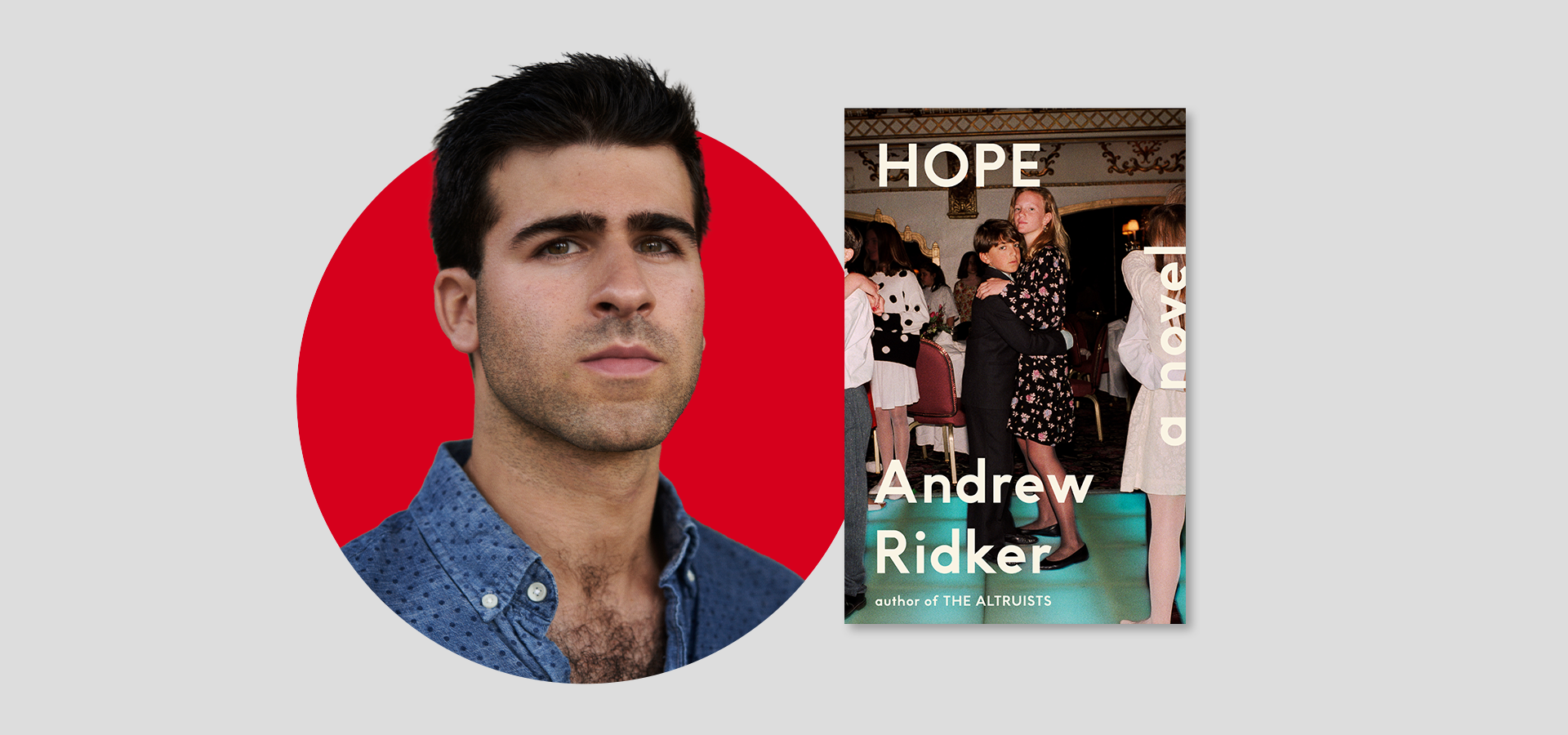

Andrew Ridker | The PEN Ten Interview

August 17, 2023

With humor, chaos, and a penchant for the unexpected, Andrew Ridker’s new novel, Hope, tells the story of the Greenspan family and the dissolution of their idyllic suburban lives. After a scandal ensnares Scott Greenspan, the family patriarch, a cascading series of misfortunes pulls each member of the Greenspan family into a reckoning with their own lives and choices.

In conversation with PEN America’s Literary Awards Intern, Anna Lasek, for this week’s PEN Ten Andrew Ridker shares insights into the structure of Hope, speaks about the writers that have impacted him, and shares his advice for emerging writers. (Amazon, Bookshop)

1. In Hope, each character embarks on a journey that makes them face and question their lives. What was the inspiration for writing such individual and complex stories?

From the beginning I imagined that the novel would be structured like a relay race, with each character holding the baton for eighty or ninety pages before passing it on. It seemed fitting that a novel about a fracturing family would itself be broken into discrete sections. Each character has his or her own independent storylines, but eventually those storylines start to intersect in subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways. In a way, the structure of the novel reflects one of its primary themes: the desire to break away from one’s family, and the bonds that invariably pull one back.

2. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

One of my all-time favorite children’s books was Frederick by Leo Lionni. It’s the story of a group of mice who work tirelessly to gather nuts, wheat, and straw for the coming winter—except for Frederick, a layabout who appears to do no work at all. But when winter comes, and the food has run out, Frederick entertains the other mice by describing the warmth of the sun, the color of the sky, and other natural phenomena he spent the harvest season noticing. Frederick is, essentially, a poet: someone who takes care to notice the world around him, and recreates it in words. My whole life has been about becoming Frederick. Parents of young children, be warned.

“In a way, the structure of the novel reflects one of its primary themes: the desire to break away from one’s family, and the bonds that invariably pull one back.”

3. What do you hope readers will learn from reading Hope?

I would be surprised if anyone learned anything from Hope. I certainly didn’t write it with the intention of educating the reader in any way. In my view, that’s not what novels are for. With that said, one of the loftier questions on my mind as I wrote the book concerned the relationship between the Obama era (when the book is set) and the Trump years (during which it was composed). In many ways, Trump was a backlash to Obama, but I was interested in points of continuity. What values, policies, and narratives were promoted under Obama, and how might those have steered us toward our embattled present? That’s one of the novel’s animating questions, and I hope readers ask it of themselves as they read.

4. Each of your characters navigates their personal decisions and desires. In which ways do you navigate truth and desires within your characters?

I’ve always been attracted to writers—Richard Yates and Edward Albee come to mind—who explore the gap between the truth and self-delusion. For me, the trick is to remember that we all live with some degree of self-delusion. I try not to place myself above my characters, in a position of judgment. Instead, I ask, “How would this character respond to a circumstance that threatens their self-image? How far would they go to avoid confronting the truth? If and when they do confront the truth—what then?”

“For me, the trick is to remember that we all live with some degree of self-delusion. I try not to place myself above my characters, in a position of judgment.”

5. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Recently, the New York Times ran a story about two Canadian men whose lives had been turned upside down. One was raised by a Métis family, and identified as “half French, half Indian.” The other was raised in a Ukrainian community. Both men identified with their family cultures, both men’s lives were shaped by their identities, and both men were stunned to discover, upon taking genetic tests, that they had been switched at birth. Genetically speaking, the Métis man was Ukrainian, and vice versa, but they had already lived full lives within their adopted cultures. I’m fascinated by stories like these because they demonstrate both the power and slipperiness of identity. As for my identity—as a man, an American, a secular Jew, etc.—it has absolutely shaped my writing. At the same time, I write to escape these categories. Maybe that’s part of the writer’s identity: a curiosity about other identities, and the boldness—or arrogance—to attempt to inhabit them.

6. One of the lines that resonated with me most occurred during the scene when Deb tries her wedding dress on again after leaving Scott and the world she knew behind. During this scene, Deb looked at herself, “…as a stranger, someone yet to be discovered”. What was something you discovered about yourself through the writing process?

For a long time, I was stuck on a novel that wasn’t working. I knew I couldn’t keep on writing it, but the prospect of giving it up made me sick. This was the novel I’d worked on almost every day for two years, the novel I’d workshopped throughout graduate school. When, at last, I did jump ship, I was crushed. All that wasted time! All that energy! But Hope arose from the ashes of that project, and I became a much stronger writer in the process. With the benefit of hindsight, I can see that nothing was wasted. I learned that nothing in the writing process ever is.

7. What is something that you feel your readers would find surprising about you?

As much as I love writing about people who seem to screw things up at every turn, I have a very low tolerance for instability and dysfunction in my personal life. My characters seek out drama, but I don’t. I wouldn’t last a week in one of my own novels.

8. What advice would you give to young writers looking to publish their own work?

Don’t! Or, to be more exact: take your time. Young writers tend to make drastic improvements year to year, or even month to month. Your best work today might soon embarrass you—a good sign!—but there’s no taking back a published piece of work. What’s more, the publication process can be an emotionally fraught experience, potentially stymying your progress. To paraphrase a former teacher of mine, Sam Chang, publishing is not just different from writing—it’s the opposite of writing. So by all means, publish, but do so when you’re ready.

“As for my identity—as a man, an American, a secular Jew, etc.—it has absolutely shaped my writing. At the same time, I write to escape these categories. Maybe that’s part of the writer’s identity: a curiosity about other identities, and the boldness—or arrogance—to attempt to inhabit them.“

9. Hope encapsulates the journey of self-realization through reflection. Were there any specific experiences you reflected on in the writing of Hope? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

Growing up in Brookline, Massachusetts—a sylvan streetcar suburb west of Boston, and the setting for Hope—played an enormous role in shaping the book. Brookline is a sort of liberal utopia, but like all utopias, it’s built on contradictions. I was eager to explore those contradictions in the novel, and when COVID-19 hit, I got my chance. I spent those first few months in my childhood home, becoming reacquainted with my hometown, albeit under strange and stressful circumstances. I paid attention to what had changed, and what had stayed the same, and those observations began informing the novel.

10. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

It seems pretty clear to me that the biggest threat to free expression in America, at least, is the GOP. Banning books, especially those aimed at kids and young adults, is so flagrantly evil I can’t imagine anyone admitting to it, much less making it a central tenet of their political platform. But here we are.

Andrew Ridker’s debut novel, The Altruists, was a New York Times Editors’ Choice, a Paris Review Staff Pick, and a People Book of the Week. It was translated into more than a dozen languages. He is the editor of Privacy Policy: The Anthology of Surveillance Poetics and his writing has appeared in The New York Times, Esquire, Le Monde, and Bookforum, among other publications. He is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths | The PEN Ten Interview

By: Malcom Tariq | August 11, 2023

This book was my attempt to assure young Black girls that there are beautiful, resonant ways to live, to investigate love, and to celebrate themselves.

Ben Purkert | The PEN Ten Interview

I followed Seth on his downward spiral and simply tried to keep up with my pen. And no, I didn’t worry that my novel was too dark. I only worried that it not be boring.

Eddie Ndopu | The PEN Ten Interview

We need to save ourselves. We need to show ourselves the kind of tenderness and compassion that we know deep down we deserve.

Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond | The PEN Ten Interview

Relations, like all of my work to date, is invested in expanding the mainstream POV to include the overlooked, ignored or unexpected.