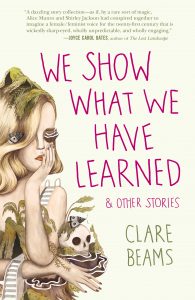

Clare Beams’s We Show What We Have Learned & Other Stories is a finalist for the 2017 PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction. The following is a story from the collection.

Clare Beams’s We Show What We Have Learned & Other Stories is a finalist for the 2017 PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction. The following is a story from the collection.

“We Show What We Have Learned”

Before her disintegration, we had long held an absolute and unwavering contempt for Ms. Swenson. She had won that with her uncertainty, which we had sensed in the very first moments of our very first day of fifth grade, the way dogs can smell fear. Waves of it rolled off her, along with the odor of cats and Kleenex and chalk that hung, unsurprisingly, in her sad, pilly sweaters. Ms. Swenson was pitiful, but this did not mean we pitied her. We felt nothing for the faded blue of her eyes, which were like a sea creature’s soft underbelly, or for the way she kept them open so wide and blinked so rapidly that she seemed to be seeing us through a mist. Her movements, too, were misty, whereas we were sharp and quick and feral. We did not wonder much about her life. She seemed ageless to us in the way that most adults seemed ageless—we could not have said whether she was twenty-five or forty—but we did know that she was younger than most of the other teachers. This was less because her face was unlined than because she seemed so much more unfinished. Everything Ms. Swenson ever said to us had a question in it, even when she explained long division or poetry, things it was clear she understood and loved, and even when she told Mark Peters to stop it when he pulled down Sally Winters’s pants and underpants to show us the hair-flecked space between her legs. The question in her voice then was simply more panicked than usual.

The day the disintegration began, we were learning about Native American civilization. We were always learning about Native American civilization—we began each year with it, and then we might, as on that day, when we were supposed to be talking about the Civil War, make several unexpected detours back to revel in the quietude of that life so close to nature. The teachers all loved these lost things—vanished ways of life, great men who died early, extinct animals—and Ms. Swenson loved them even more than most. We watched while she drew a wigwam on the board. Ms. Swenson was very bad at drawing, worse even than the worst of us, because she was crippled by second guessing. She darted in to draw a line, darted back to look at it, darted back in to erase it and start over. “Is that straight?” she asked us, but wasn’t it supposed to be rounded, wasn’t that the whole point? Finally she sighed in a way that meant she was giving up and settling for the misshapen thing she had produced. “You see, children, the hole was put there,” she said, pointing, “so that the cooking smells could escape. It’s ingenious.” Her hands began to wave desperately and hopelessly, as if she were trying to breathe with them, like vestigial gills. There was something beautiful about her excitement in these moments, irresistible target though it was. “The early colonists were never so ingenious. In many ways, the civilization they would brutally overpower was vastly superior to their own.”

Abner Harris raised his hand. Ms. Swenson never did learn not to call on him. Perhaps she was distracted by the glimmering vision of wigwams in her mind, a whole village of them where she might have lived gently and happily in our absence. Tending plants, fetching water from the stream, watching smoke rise toward bright stars. “Yes, Abner?” Ms. Swenson said.

“Is that what holes are always there for?”

“Is what what they’re always there for, Abner?”

“So smells can escape? Is that what, like, Rachel’s hole is there for?”

“Rachel’s hole?” Ms. Swenson said, musingly, still failing to understand, though Rachel was already blushing. When Ms. Swenson got there, two red spots appeared high on her cheeks. “Abner, that is inappropriate,” she said and yet managed to sound as if she were asking for permission to reprimand him.

“What is?”

Mock innocence was mortally wounding to her; she couldn’t help taking it at face value. We waited, snuffling into our hands and tasting the salt of our palms, chewing on the skin around our fingernails with the glee of what was coming.

“To speak about the . . . ” she flopped like a speared fish, “private parts of others.”

“But Ms. Swenson,” said Billy Nichols, drawn to the blood in the water, “which parts are private? I forget.”

We squeaked our sweaty hands against our desks in joy. Now she would have to say them, say those words. What could be more wonderful? We would hear them from her lips.

And that was when it happened. We would wonder, ever after, what caused it: the force of the bottled-up, forbidden words we were calling forth or the hammering blows of the humiliation we were delivering. Whether the force came from within or without. Ms. Swenson, in her agitation, flicked her webby hair behind her ear, chalk still in hand, and in the process flicked some object off herself. It flew forth with so much force that the act would have seemed intentional but for the puzzlement on her face. An earring, we assumed, at first. But the earrings Ms. Swenson wore were not as large as this.

Hannah Perkins, in the first row, began to scream. She was peering over the edge of her desk at the thing on the floor, and she curled her feet up under her as if to keep them away from a mouse. We left our seats and clustered around the space in front of Hannah’s desk.

The thing on the ground was an earlobe.

Detached, it looked very fleshy, though Ms. Swenson had never before seemed to have especially fleshy ears. It sat on the ground like a fat, self-satisfied grub, one that had perhaps eaten its brethren. Ms. Swenson’s small gold hoop earring was still in place, puckering the roundest part of the lobe’s belly. There was no blood; there was simply one ragged edge. Naturally, we looked from there to the rest of Ms. Swenson’s still-attached ear, the matching puzzle piece, the yin to the lobe’s yang. No blood there either—the gap made us queasy, but it seemed more the result of a shedding than of a wound. Then we looked at her face.

“Hmm,” Ms. Swenson said. She turned away. We thought she might begin to scream. Instead she went calmly to her desk, swished a tissue from its box, and returned to the lobe on the carpet. She covered it with the tissue, and for a second it seemed she might leave it there, a small sheet over a small corpse. Then, with an expression of distaste, she reached out and lifted it just as she might have lifted a dog turd. She walked back to her desk, opened the drawer, and placed the lobe inside. She shut the drawer softly. Only then did she look at us. She seemed to have just remembered where she was.

“I can trust you, I think,” she said, “not to mention this to anyone.” We were surprised by the lack of a question in her voice.

Our classroom was quieter than it had ever been. If she planned for this to stay a secret somehow, we would not give her away. We nodded, twenty-six heads in unison, the first grown-up promise we had ever made, one of the few some of us would ever keep.

“Now,” said Ms. Swenson, “I believe we were discussing the wigwam.”

Here are the parts that Ms. Swenson lost in the days that followed: three molars, the end of her nose, a chunk of one shoulder, which she shook from her sleeve, her lower lip, and assorted fingers and toes, including all of the fingers of her right hand except the thumb. She still managed to hold the chalk by pinning it between thumb and palm. Her penmanship didn’t look much different than usual. We applauded this triumph, literally applauded it with our shamelessly whole hands, and she acknowledged the tribute with a nod before continuing with the lesson. There was something different about her lessons now. We were attending to them anew, horrified, rapt. Ms. Swenson was not a dramatically better teacher than she had been before—she still apologized and bobbled, though the missing lower lip gave her an irritated expression—but we were dramatically better students. We wondered which words would move her enough to move a piece off of her, and the wondering made us really listen to those words, which made us learn from them, in most cases for the first time. We learned to multiply and divide large numbers gracefully, to conjugate French verbs, to spell “ambiguity”; we learned the order of Civil War battles and the types of rocks—igneous, metamorphic, sedimentary. This progress was so painless it was scarcely noticeable to us. In becoming a mystery, Ms. Swenson had gained our devotion. Our love and our fear of her grew in direct proportion to the little sheeted mounds in her desk drawers. One day at recess, Tom Milk brought out a tissue bundle he said he had stolen from the desk; he claimed it was the left index finger we had seen her shed two days earlier. His reluctance to let us see it was a tell, though, and when Shawn Greggors seized it from him and shook it out, nothing but more tissues emerged to dance away across the pavement. You could not have paid us, any of us, to touch the genuine relics.

It was a month from the first earlobe to the culmination. We had suspected some end must be nearing—What can be left? we’d whispered—but still we were unprepared.

Ms. Swenson was explaining the mating rituals of frogs. “The male gives a little call like this: whoo whoooo.” She sounded more like an owl. She crouched down to approximate a frog with her carriage. “He tries to call as loud as he can. The female hears the call and thinks, Oh my, what’s that? And then she gives a little hop.”

This was where Ms. Swenson forgot her limitations and gave a little hop of her own to demonstrate. It was a small hop, but it was enough. In addition to the thump of her weight as her feet hit the ground, there was a sound like wet cloth tearing. Both of her legs detached somewhere near the hips and fell away beneath her skirt. Her torso plummeted. “Oof,” she said with the impact. Her shoulders separated from her chest. Her head separated from her neck and landed facedown on the carpet.

There was a silence.

“Okay,” Ms. Swenson said. Her voice was carpet muffled, bright with effort. “That wasn’t so bad. Not as bad as I thought it would be. Stephanie?” Stephanie was the girl at whose socks Ms. Swenson was now staring. “Stephanie, would you please put me on that chair?”

Stephanie did not want to touch the head, we could all see this, but how do you refuse a request like that? She picked Ms. Swenson up, holding her far away from her own body, and carried her toward a chair at the front of the room. She had to step over Ms. Swenson’s torso to get there, and she looked down, seeming to consider and then dismiss the possibility that she was responsible for it too. “At least that’s over,” Ms. Swenson said en route.

When Stephanie put her down, though, we could tell it wasn’t over yet. A great hunk of Ms. Swenson’s hair came away in Stephanie’s hand; Stephanie shrieked softly and brushed it off against her pants, where it clung for a moment before falling to the floor. Ms. Swenson didn’t seem to notice. As we watched, one of her eyebrows lifted from her face like peeling paint and fell in a curl to the seat of the chair. Her upper lip was starting to look crooked. “Children, we must be quick, now,” Ms. Swenson said. “It is time for you to show what you have learned.”

We misunderstood her at first. We rummaged frantically for pencils and paper. Some of us set to work multiplying and dividing; others began to spell out previously elusive words. Still others began lists of facts. We could have filled pages and pages with those facts. We could have wallpapered the classroom with them.

“Not that!” Ms. Swenson said. We looked up at her. An eyelid slipped its moorings. “Is that all you know? Is that all I have taught you?” Her panic had set the eyeball beneath the crazily hung eyelid rolling; we wondered if she could still see out of it.

We waited for her to regain her composure and tell us again what we were to do. We wanted to please her as much as we had ever wanted anything.

“You must see,” she said. “It’s your turn, children. You’ll have to, you know. And haven’t I been demonstrating for weeks now? Haven’t you been paying attention? All of you ought to know by now how it is done.”

Those of us who had understood were hoping we hadn’t. Ms. Swenson’s patience had run out. “Show me, children!” she screamed. “Come apart!”

But the force of that p was too much; it blew her upper lip clear off. Her gaze followed it as it sailed away from her, hit the edge of Stephanie’s desk, and stuck, and she seemed to surrender. We had thought the finale would be spectacular. We had been waiting for days for her eyes to pop cartoonishly, for her to fling a moist slab of tongue toward us. These things did not happen. She just gave a sigh, and her head sank to one side a little, and that was all.

All except for the feelings we felt next.

It began differently for each of us, Ms. Swenson’s final lesson. Some of us felt it gathering in the tiny bird-bones of our fingers, some in our hard, pink, healthy gums. For some, it came first to the pristine joints of our vertebrae. For still others, it settled in the unobstructed tunnels, lustrous and smooth, that led into and out of our childish and unscarred hearts. But though it took so many different forms, the beginning was universal. Not even the most whole among us was exempt. You would not have seen a difference to look at us, but we had changed, were changing, as our seams learned how to loosen. We were becoming divisible. We would come to understand that in this way, Ms. Swenson had prepared us.

For the future is gated, and there are tolls to be paid.

Excerpted from We Show What We Have Learned. Copyright © 2016 by Clare Beams. Used by permission of Lookout Books, an imprint of the Department of Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.