Manuela Hoelterhoff and Emad Tayefeh share an interest in politics and art, and for three months last year, they shared a home.

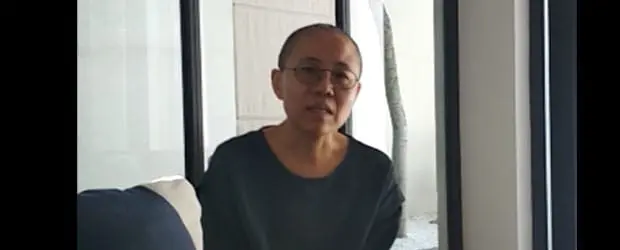

Tayefeh is an Iranian filmmaker who fled Tehran in August 2015 having been repeatedly jailed for documenting the political repression in his country following the 2009 Green Revolution.

After a perilous journey through the forbidding mountains of northern Iran and on to Turkey, he arrived in the United States a year later. Tayefeh found refuge at the home of Eve Kahn, a former art columnist for The New York Times. Several months later, Kahn led Tayefeh to Hoelterhoff.

A Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and culture editor formerly at The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg News, Hoelterhoff frequently opens her New York apartment and upstate farm to needy cases, usually of the four-footed kind. She has rescued cats, one mule, horses, a raccoon, goats, pigs, and quite a number of beagles ever since reading about Sugar, a dropout from the Beagle Brigade—canine professionals trained to sniff out illicit agricultural products at international airports. Sugar needed a home. That was nearly 20 years ago.

When Tayefeh stepped through her door, three replacement beagles barked their welcome.

“Living here was really fun,” remembers Tayefeh, now 32, when he recently returned from Chicago to visit his benefactor. “With the beagles, the view, and with her. It’s like a dream.”

“Like a refugee club,” responds Hoelterhoff. After Tayefeh received an offer to teach Iranian film and history at Northwestern University in Chicago last January, he was eventually replaced in the Hoelterhoff home by Raad Rahman, a reporter from Bangladesh, whose life had been threatened by extremists for writing on LGBT issues. Both have been assisted by PEN America in their journey to safety and stability.

As one might expect of a culture editor who has also written a book on the opera world, Cinderella & Company: Backstage at the Opera With Cecilia Bartoli and the libretto for David Lang’s Modern Painters (about the Victorian tastemaker John Ruskin), her apartment overlooking Central Park is filled with art, including a small Christo of his Reichstag project and a surrealist picture of humanoid birds by Leonora Carrington. Tucked into corners and perched on pedestals are ceramic turtles and carved pigs. In New York realtor parlance, the apartment is a “classic six,” containing a small room and half bath off the kitchen that in a previous era would have been for the maid.

“I was sitting right here in the living room by the windows with Eve Kahn whom I’d known off and on since my Journal days. We were catching up, and at one point she said ‘I have an Iranian in my TV room.’”

“What did you just say?” I asked.

“There’s an Iranian in my TV room, and my husband is thinking maybe it’s time to get the TV back.”

“Well,” I said. “I happen to have a maid’s room in the back and no maid.”

Tayefeh laughs. “Eve told me she knew a lady who used to work for The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg. She said I could move to her place. And I said, ‘Wow. You don’t like me anymore?’ And Eve said, ‘We like you—but Brad likes to watch TV.’ And I said, ‘OK, I understand. I’m a guy, too.’”

The two met a few nights later when he arrived at her door with one suitcase and a backpack. “He looked somewhat like a panda bear and that was in his favor,” remembers Hoelterhoff.

The first week was an adjustment for both Tayefeh and Hoelterhoff. In order to avoid imposing, Tayefeh would stay in his room or hurry out in the mornings with his camera to meet the filmmaker Joan Schimke, who was helping him edit Saeed, a film about a Syrian woman he met in Turkey.

Eventually relations warmed as Hoelterhoff noticed her guest Skyping with his mother in Tehran and asked him to help her with Instagram and Facebook. Soon Daisy Mae, the oldest and smartest beagle, was also Skyping with Mrs. Tayefeh, a highly regarded screenwriter and set designer.

“Obviously, it was rather amusing to note how skilled Emad was in communications and also how much he knew about American culture, especially film. I knew a lot about ancient Persia and have a friend who is related to the last Shah, but I had a dim understanding of the Iran of today. So many surprises. The great number of women in professional classes like architecture and engineering. And the focus on learning foreign languages. When Emad started to learn English in grade school, he even had a choice of American or British accents.”

Looking back on this time, Tayefeh says, “We laughed with each other. She asked me to invite my friends here, play piano, and cook Persian dishes.”

He is remarkably calm as he describes the years in prison cells so small he could barely stretch out. He remains unsure why, on a night when several other prisoners were lined up and executed, he was spared. “My parents had been brought to the prison to say goodbye,” he recalls.

If the intent was to scare him, it worked. The next time he was let out, Tayefeh stuffed a rucksack with his laptop, a hard drive filled with his work, some clothing, and the nuts and biscuits his mother gave him to eat on the road. On bus and on foot, he traveled to the Turkish–Iranian border, where he bribed the guard to let him pass. He then spent the next 10 months in Turkey navigating an already burdened refugee system before receiving a humanitarian parole visa that brought him to New York.

Hoelterhoff is an immigrant herself, the daughter of a German father and a Latvian mother who left Hamburg in 1958 when she was eight years old. “My first memories are of war ruins: We went sledding down a hill of rubble next door to my building, probably on top of corpses burned in the bombing. My father was one of the few survivors of Hitler’s doomed Sixth Army at Stalingrad and traumatized for life. My mother never forgot her house in Riga and never really relocated mentally: We lived out of cardboard boxes and Salvation Army castoffs.”

Tayefeh was appreciative, he says, that both his hosts never pushed him to talk about himself. “Manuela and Eve, they don’t force you to do something. They let you choose and they let you stay. In this way, it becomes like a home, because in your home no one forces you to do something, no one asks you to explain something.”

“I didn’t want to ask too many questions because I wasn’t here to interview him,” Hoelterhoff says. “I was here to give him a room with a door on it and some quiet and time to think.”

And for displaced artists like Tayefeh, stability is imperative.

“People are always asking me about ways to provide help, and hosting a writer at risk is one of the most practical ways to assist,” says Karin Deutsch Karlekar, director of Free Expression at Risk Programs at PEN America. Karlekar was instrumental in helping connect Tayefeh to the Northwestern opportunity. Much of PEN America’s ability to coordinate these opportunities, however, hinges on timing—when the writer arrives in the United States and what fellowships may be available. “It was very fortuitous that we got this opportunity, but Emad still had to apply and wait. In the majority of cases we work on, a positive resolution can take many more months and sometimes over a year.” A safe haven helps so much while you wait.

Tayefeh recalls his first few weeks in America as a whirlwind of having to “go to a lot of places, talk with a lot of people, sign a lot of papers, and explain so many things.” And for someone who has already been displaced, the emotional burden and stress is only intensified by confusion and fear.

“If you don’t have any place to stay, the pressure only increases,” says Tayefeh. “But when people give you a place to live—when they trust you to live with them—suddenly that makes all the difference.”

“Because of unexpected setbacks in my own life, I ended up losing an apartment I loved and the financial and emotional security that went with it. This absurdly large rental is the result, an outcome made happier by sharing,” says Hoelterhoff. “But in my dreams, I have traveled back to the lost flat where I spent 20 happy years. The sense of loss is there.”

“My financial situation is actually modest, but this is the way I can help writers from far away move into a new life. More people with too much real estate should think about it. If you have an extra room, think about what you can do for amity in a time of hostility. I mean, there is so much hostility, especially against Muslims. It’s completely nonsensical and toward people most of us don’t know.”

And for Tayefeh, the filmmaker’s time with Hoelterhoff taught him that there were other ways, besides donations, to give back. That was a lesson he took with him to Chicago, where he assists recently arrived refugees with their transitions. “I learned from Manuela and Eve, and I’m going to teach others, and it goes and goes. Maybe there will be 10 more people after me. If a lot more people do this, we’ll have a bigger result.”

Cautions Hoelterhoff: “Look. Your new best friend is probably not going to walk through the door. Don’t expect that. But there could be someone making coffee and sharing stories. And that has made me happier. Not really happy, but happier. It minimizes a sense of solitude.”

“Any person that comes to this country as an immigrant or refugee has to start from somewhere,” Tayefeh says. “I know that all of us in this society have our own problems, that’s understandable. But helping each other makes our society better. Everyone could go into their house, close doors and windows, and say, ‘It’s not my business.’ But that means that others are left outside.”