Today marks the 36th annual Day of the Imprisoned Writer. On this day each year, PEN International and its centers around the world highlight and campaign on behalf of writers who face unjust imprisonment as a result of their work.

In recognition of the Day of the Imprisoned Writer, PEN America Senior Manager of Free Expression Programs James Tager examines the conditions for writers jailed in China, where denial of medical treatment is a common tactic for punishing the country’s dissidents.

When you meet a famous writer for the first time, what they say has a tendency to stick in your head. But I only remember one phrase from when I first met Paul Auster: “They killed him.”

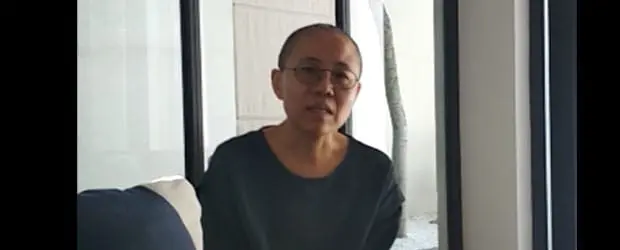

Auster was staring at a poster of Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize winner and Chinese writer. Liu had died that morning of liver cancer, only 21 days after being released from prison on medical parole, and Auster had come to a vigil and poetry reading to commemorate his life. “They killed him,” Auster repeated to me. I knew exactly what he meant.

As a matter of medicine, it was of course cancer that took Liu’s life. But the responsibility for his death must rest on the shoulders of the Chinese state. Liu Xiaobo was serving an 11-year sentence for “subversion” when he died, and authorities waited until he was terminally ill before they released him from prison. His last few days became a micromanaged farce, with authorities releasing crass promotional videos while challenging the decisions of foreign doctors who said it was not too late for him to seek treatment abroad.

But while his last days were subjected to the indignity of medicine-as-propaganda, the real question is how and why Chinese authorities took action only when Liu’s condition had become terminal. Liu suffered from hepatitis B, a condition which dramatically increases one’s risk of liver cancer. And yet it seems that his jailers only could be bothered to notice the state of his health mere weeks before his death.

Weeks after Liu Xiaobo’s death, we at PEN America learned that Yang Tongyan, another well-known Chinese writer who had similarly been convicted for dissident activities in connection to both his activism and his writing, had been diagnosed with a particularly fast-moving and malignant form of brain cancer. Yang was granted medical parole on August 16 and moved to a specialist hospital, but was denied permission to leave the country for medical treatment due to his status as a “criminal,” despite his family’s wishes to pursue treatment abroad. He died on November 7.

Yang Tongyan was serving a 12-year sentence: His family had previously sought medical parole for him twice and had been denied twice. Yang suffered from tuberculosis, diabetes, high blood pressure, and nephritis. He had previously been in critical condition—in 2009, Yang’s sister visited him and said he had become so thin as to be “unrecognizable.”

With both Liu and Yang specifically, it is clear that the circumstances of their medical parole—after they had already become terminally ill—had more to do with controlling bad publicity than with medical treatment. China did not want to suffer the embarrassment of having their internationally known writers die in prison. Even after they were released on medical parole, both Liu and Yang were cut off from friends and colleagues, denied the opportunity to speak freely. When Liu and Yang were on their deathbeds, their government was concerned not with its citizens’ well-beings but with its own reputation.

In fact, upon Liu Xiaobo’s death, observers noticed a dramatic uptick in censorship of anything related to Liu: Even his given name, Xiaobo, was enough to trigger censorship. The Chinese government cared enough about what Liu represented to censor even his name, but did not care enough about the man to provide him with anything approaching adequate medical treatment until it was far too late.

Both Yang and Liu were recipients of PEN America’s Freedom to Write Award, awarded yearly in recognition of writers who have paid a high price for their refusal to self-censor. China has the dubious distinction of having the most Freedom to Write Award winners: seven. A third Freedom to Write Award winner from China, the Uyghur academic Ilham Tohti, is currently serving a life sentence on charges of “separatism.” Tohti is also supposedly in ill-health: He has lost significant weight in prison, in part because the prison provides insufficient amounts of halal food.

The Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders noted this August that “dozens of political detainees and prisoners have reported being deprived of adequate medical treatment.” They concluded that “Deliberately depriving political prisoners of medical care . . . appears to be commonly used against political prisoners on China.” Frances Eve, a researcher for the group, noted that there is “a real fear amongst prisoners of conscience and their families that authorities aren’t afraid to let them die from lack of adequate medical care.”

Nicholas Bequelin, East Asia director of Amnesty International, has offered a similar assessment: “In many cases seriously ill imprisoned activists are being granted medical parole late, and their families’ wishes for treatment outside of detention or abroad are ignored. There seems to be no accountability for the pattern of death on medical parole for people labelled by the authorities as ‘enemies of state.’”

Whether through deliberation or through depraved indifference, Chinese authorities are wielding the denial of adequate medical care as a weapon against their dissidents, including writers and those who have been jailed simply for their peaceful exercise of free expression.

Yang Tongyan once wrote—in a 2005 jeremiad published in The Epoch Times—“fear flows everywhere in China . . . Government officials are afraid of losing their power.” Liu and Yang died of cancer. But they also died as a result of their government’s fear of them: their words, their activism, and their strength as symbols of freedom and conscientious protest.

Healthcare as propaganda. The denial of healthcare as a weapon. The image of the Party over the life of a sick individual.

I agree with you, Paul. They killed him. They killed him.