On April 23, in Seoul, visual artist Taeyong Jeong (aka HIDEYES) stood trial for the destruction of public property, a charge leveled against him for spray-painting symbols of peace on a section of the Berlin Wall installed in Seoul’s Berlin Square. The proposed penalty for his work of graffiti was a prison sentence of one year. His defense argued that HIDEYES used his art as a vehicle to communicate his ideas, feelings, and political opinions in a gesture perfectly concurrent with the Wall’s long history as a graffiti-adorned canvas of free speech. The jurors did not share these sentiments, though the guilty verdict carried a fine of 5 million won, the equivalent of $5,000 USD, rather than a prison sentence.

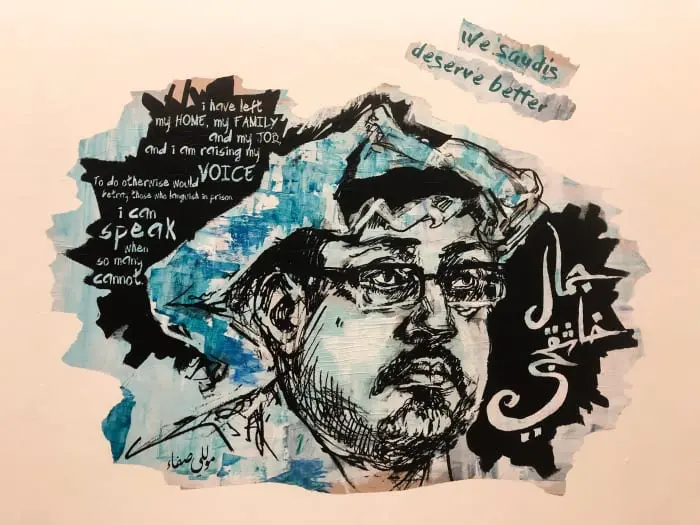

Seoul’s section of the Berlin Wall was a gift from the mayor of Berlin, Klaus Wowereit, in 2005. He acted in the spirit of friendship and solidarity with a country facing a familiar political divide of friendship and solidarity with a likewise politically-divided country. It was in this same spirit that HIDEYES created “Look Inside,” a work of graffiti on June 6, 2018—Memorial Day in South Korea—to commemorate the April 2018 Inter-Korean Summit, the first step toward reconciliation between North and South Korea in 11 years. He built upon the Wall’s foundation of bifurcated memory and identity, carrying on the practice—in its new Korean context—of embellishing the Wall with messages of sincerity, meaning, and hope. His painting featured the Taegukgi and the ying-yang symbol in the middle of the Korean flag to speak about separated families, a sensitive social and political issue in the Korean peninsula.

HIDEYES reached out to the Artists at Risk Connection (ARC), seeking legal assistance. ARC Director Julie Trébault contacted me at Avant-Garde Lawyers in her search to connect him with a lawyer. We knew the case would create controversy, but we also saw its potential to foster discussions about street art, free speech, and the symbolism of the Berlin Wall. It is precisely for these reasons that we have fought tirelessly on behalf of HIDEYES to elevate this case as an example of the stigma street artists face around the world.

An artist’s job is to use non-verbal and symbolic means of expression to make a statement about the realities of our time. One of the most famous contemporary artists is the anonymous graffitist Banksy, whose work can be found in public spaces around the world. HIDEYES, like Banksy, deals with issues worthy of our attention. We have to ask ourselves: Would Banksy be on trial in South Korea if he had painted Peace Soldiers, one of his most evocative murals, on Seoul’s Berlin Wall?

In the absence of an explanatory context, HIDEYES’s work can be easily dismissed as a senseless provocation. Even before HIDEYES’s mural, Seoul’s Berlin Wall was full of drawings from Korean passersby. “I did not even know it was something of importance. I would see people smoking cigarettes and leaning against it. I have always wondered what it was. Now I know,” says Teri Kang, a local lawyer who works near Berlin Square and decided to join HIDEYES’s defense team.

In the ephemeral and ungoverned world of street art, graffiti artists have their own language and codes. If one paints over another’s work, the new graffiti must be better than what stood before. Moreover, this is as close to a law as there is; it is a practice called toying. Nobody expects graffiti to last forever. When HIDEYES painted over the initial markings on the Berlin Wall, he intended to improve it. There is a specific technique to graffiti that goes beyond spray cans, a search for colors and forms that HIDEYES carefully planned and executed beautifully. According to the scholar and artist Don Karl, whose expertise in graffiti qualified him to issue a supportive opinion of HIDEYES before the Korean court, “’Look Inside’ was a beautiful and meaningful work which could well have had an important historical meaning in the future, just like some of the pieces in Berlin have become a national treasure at the East Side Gallery.”

A criminal court should not have been the place to judge HIDEYES, and a custodial sentence would be an unjust form of punishment. According to international standards for the protection of freedom of expression, restrictions on free speech in the form of criminal sanctions are only acceptable in cases of incitement to hatred. Taeyong’s graffiti contained no elements of violence, nor did it stir up hatred or intolerance toward others. On the contrary, the graffiti communicated in an original and aesthetically pleasing manner a clear message calling for peace and reunification between the two Koreas.

Freedom of expression is one of the primary conditions for progress in a democratic society and each individual’s self-fulfillment. The possibility of criminal sanctions, especially imprisonment, represents a profoundly chilling threat to such freedom. A prison sentence for HIDEYES would have been a serious step in the wrong direction, sending the dangerous message that non-violent forms of artistic expression could land artists in prison in South Korea.