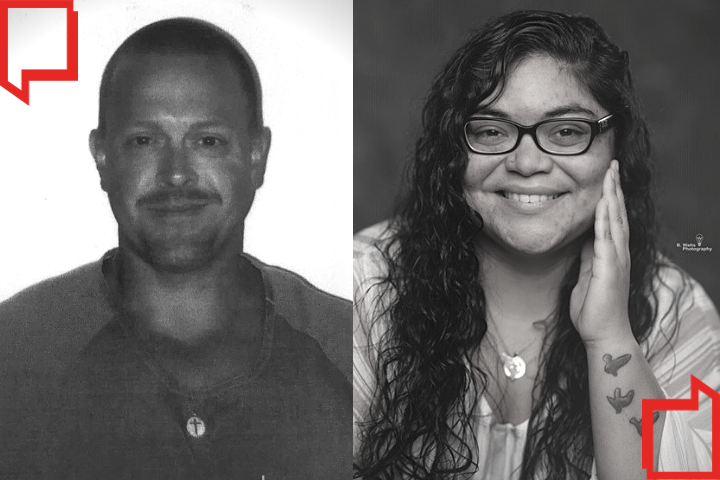

Daniel Pirkel was awarded an Honorable Mention in Nonfiction Essay in the 2022 Prison Writing Contest.

Every year, hundreds of imprisoned people from around the country submit poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and dramatic works to PEN America’s Prison Writing Contest, one of the few outlets of free expression for the country’s incarcerated population.

On September 14, 2021, my brother Josh killed himself at about 5:15 in the morning. Only 31 years old, Josh had spent his life looking for positive social relationships, and found mostly rejection. Despite exacerbating his mental health issues when I was a boy, more recently, I was one of the few people who helped him cope with his schizophrenia. However, my incarceration, with its severe length and conditions, hindered our relationship, contributing to my brother’s tragedy.

While the loss of social connections is a natural result of a prisoner’s removal from society, American correctional systems have adopted unnecessary policies that stifle relationships. For instance, many states house inmates hundreds of miles away from home. While sometimes necessary depending on a department of correction’s infrastructure or a prisoner’s security level, officials often refuse to consider a prisoner’s social needs when closing old facilities, opening new ones, or transferring prisoners. For instance, the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) built multiple prisons in the Upper Peninsula (UP) in the 1980s, even though most of Michigan’s population live hundreds of miles away. Despite closing down many new prisons in the Lower Peninsula since then, UP facilities remain open for housing, even if they have no disciplinary records.

Rather than ensuring that prisoners live as close to home as possible, the MDOC randomly sends people to the UP and then requires them to wait 3 years before being placed on a waiting list to be transferred down state. Before going to the UP, I received at least 1-2 visits a month. In the UP, I received 1-2 a year. However, Josh’s mental condition made it nearly impossible for him to visit me while I was incarcerated in the UP, as it was an 8 ½ hour drive from his home in Indiana compared to the 3 ½ hour drive to the prison in Ionia where I was housed before my stint in the UP.

After four years, I was transferred back to Ionia (at MTU) because I was accepted to a college program. Although I do not know how long it would have taken to be transferred down state had I not received this good fortune, the damage was already done: my brother’s mental condition had worsened, and our relationship had been strained.

Aside from visitation, the MDOC’s policy on prisoner phone calls further strained my relationship with Josh and numerous other relationships over the years. When I was first incarcerated in 2008, a 15 minute phone call cost about $12. While this cost has fluctuated over the years, it has more recently hovered around $2 for 15 minute phone calls (the time at which the call is automatically ended and cannot be reused for 15 minutes). Since I made between $25 and $35 per month during the first month of my incarceration, I was mostly able to call loved ones who could afford the calls themselves, namely, my Mom and Dad. Though I occasionally talked to Josh because he was close to my parent’s phone when I called, he usually was not, making our relationship sporadic at best.

Aside from the cost of phone calls, most facilities do not contain enough phones to meet prisoner demand. The result creates a dog-eat-dog mentality in some prisons, wherein gang members control who uses the phone, selling time slots to their friends and the highest bidder. On Christmas of 2020, I spent 2 hours waiting for the phone only to be cut in line. After voicing my displeasure, several gang members promptly threatened me with knives. This conflict can be blamed on prison administrators as well as Global TelLink (GTL), a private phone company that makes hand over fist through their monopolies over the prison phone systems in many states.

Prison administrators rarely attempt to improve a facility’s infrastructure to ensure that it accommodates prisoner needs met. Administrators also rarely intervene on prisoners’ behalf to ensure that private businesses do not take advantage of them or to improve their services. However, MTU (my current facility) allegedly asked GTL to install additional phones in May of 2021, but MTU was rebuffed, as the facility “did not provide enough phone traffic to justify the cost.” This may have been true for some of the units, but prisoners were keeping all of the phones busy from 6:15 AM until they were turned off at 11:20 AM. Either MTU did not actually ask GTL, or GTL did not take its request seriously.

COVID made the fight for phones and contact visits significantly worse, as MTU allowed no contact visits from March of 2020 until June of 2021. Now, MTU technically allows visits, but few people are able to engage in them. For example, my housing unit is limited to 12 visits per week, even though my unit houses 240 people. Not only do these visits require masks and a plexiglass barrier that prevents anyone from hearing each other, but many people cannot figure out how to use the GTL app necessary to sign up for visitation (my parents included). Allegedly, these measures are “necessary” to protect inmates, despite the fact that 80-90% of MTU’s population has been vaccinated since March 23, 2021. In other words, prisoners at MTU have been essentially denied visits for a year and a half, and COVID should not have been a factor during the past half year. Had Josh been able to visit me anytime between March and September of 2021, he might still be with us today, and I would not be writing this, crying my eyes out.

Despite how prison has contributed to destroying my relationship with Josh, I feel a significant amount of guilt for my brother’s death. Like many incarcerated people, I was the center of my family’s social circle. Once incarcerated, many families no longer celebrate holidays together, or such occasions are more somber than usual. In the last year of my brother’s life, he retreated from such events, perhaps because they were reminders of an unpleasant past, much of which is my own fault. I treated my brother poorly until I turned 16, when I realized how much I had been hurting him. Then, I was incarcerated three years later (2007).

While I am 100% responsible for harming my family, victims, and community by engaging in criminal behavior, my 22 year minimum contributed significantly to my brother’s mental breakdown. The national average time served for my crime (attempted murder) is 10 (?) years, and had I been released or had any hope of release around this time (which would have been in 2017), I would have been able to help my brother cope with his mental health issues. No one can know for certain if I would have prevented Josh’s suicide, but we do know that the criminal justice system needs reforming in a variety of ways, particularly in helping prisoners keep in contact with their family members.

Research indicates prisoners who regularly receive visits and phone calls are less likely to recidivate. Instead of encouraging such connections, the U.S. prison system largely disrupts them through bureaucratic indifference and facilitating private business interests who profit from the poorest and most vulnerable people in society. Such politics do not benefit the public, but endangers it instead. We need to push our governors and legislatures to open correctional facilities up for visitation and to improve their phone and mail systems to make prisoner communication easier. Perhaps we can stop future tragedies from occurring.

Purchase Variations on an Undisclosed Location: 2022 Prison Writing Awards Anthology here.