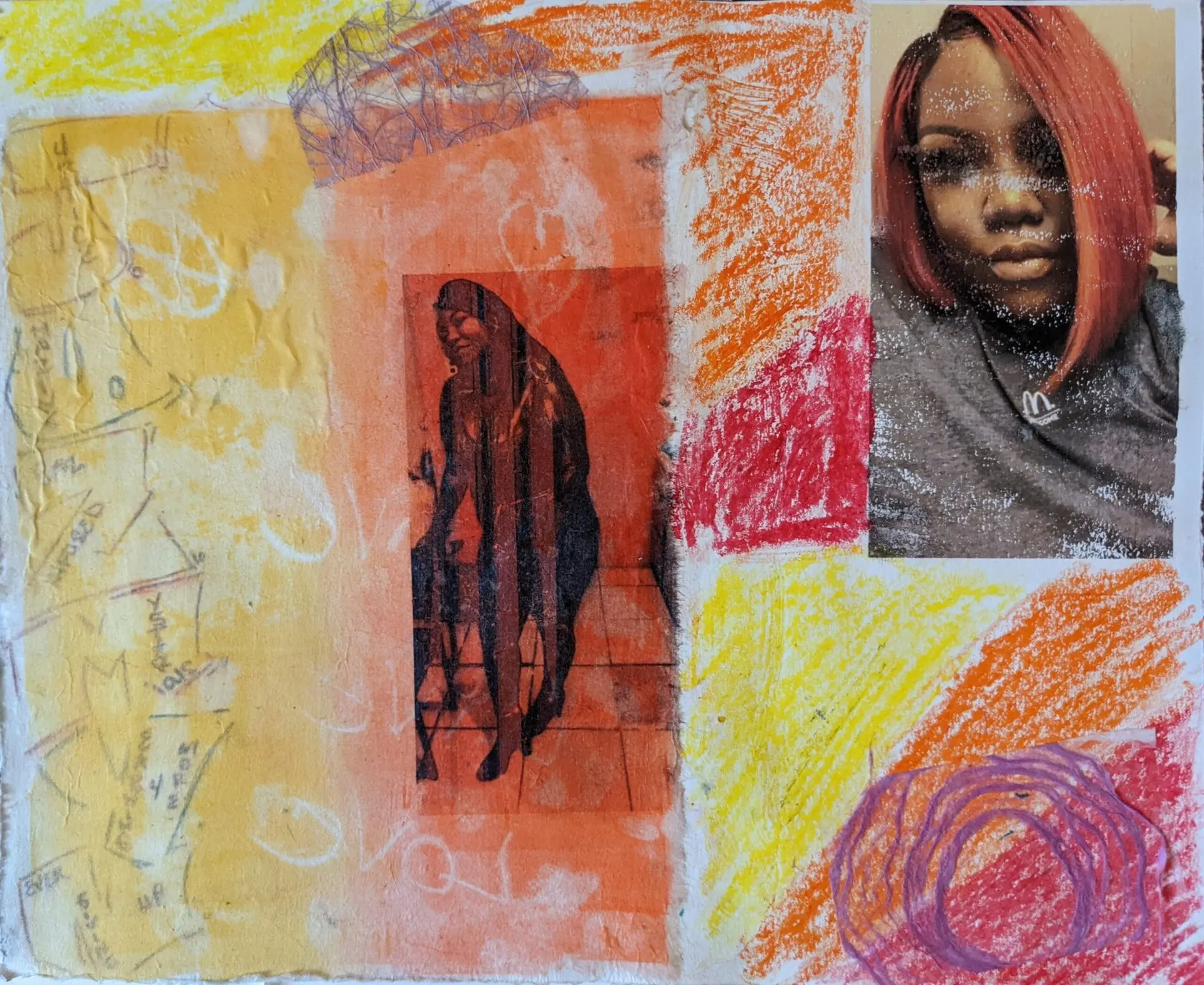

Geneva Phillips was awarded 3rd Place in Nonfiction Memoir in the 2022 Prison Writing Contest.

Every year, hundreds of imprisoned people from around the country submit poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and dramatic works to PEN America’s Prison Writing Contest, one of the few outlets of free expression for the country’s incarcerated population.

There is an exaggerated metallic thunking, the air-hiss of the heavy gauge locks. I wake as the door shaped slice of fluorescence swings wide, revealing a vaguely humanoid blob punctuating the blinding brightness.

The voice of command sounds, “Phillips! Pack up; you’re going to Eddie Warrior. Be downstairs before the 5:30 count.”

I automatically squash the resentful, anti-authoritative default setting and all the unwise responses it elicits. I watch silently as the door swings abruptly closed, with a much softer and less permanent click.

I feel the deep and sudden dread of irrevocable change sweeping over me. I look at the cheap clock radio, red number glaring at me like I am glaring at it. 3:00? Two hours, give or take, to sort through, pack up and discard all I can’t take with me. The last seven years come down to this moment. I can’t stop it any more than I could stop stepping off the prison bus in the first place. Any more than I can stop discharging in another seven years. This is, actually, one of the hardest parts of prison, a part that persists unrevealed to the world at large. It is rarely ever, if ever, discussed among inmates themselves. It is the recurring trauma inflicted with relentless regularity upon the repeatedly traumatized.

The ripping away of people.

Being ripped away.

3:00 a.m. guarantees that no one knows I’m leaving. No goodbyes. No closure. There are no healthy entrances or exits to this prison life.

It is, for the most part, understood and expected—sometimes with disturbing amounts of callousness and disdain— that prison is rife with hardships. The most common of them are discussed openly among inmates and their families, by reformists and even occasionally by the media. Hardships such as the loss of contact with family. The lousy food, lack of food and viable alternatives for nutrition, lack of opportunities for rehabilitation, personal growth, and healing. Mental health and medical care. The loneliness, the bankruptcy of compassion and hope that comprise the day-to-day reality of prison life.

There is, though, a hard part that no one talks about. Not in prison and not outside of prison. It is this: the constant reinjury of the wounded. The re-losing of every emotional bond forged over the course of years in a “held hostage” environment. An environment steeped in abandonment and grief inflicted upon women whose only constancy lies in the constant assurance of more loss.

To look at the pervasiveness and inherent damage done over the course of incarceration, I’ll need to go back to the first point. If you will recall, there are two: 1. The ripping away of people, 2. Being the one ripped away.

It started in county jail. I found myself surrounded with strangers: ripped away from all that was familiar, comfortable or normal (let us put aside for a moment the fact that just because something is comfortable or normal or familiar does not mean it is healthy or wholesome—it is still all that is known and all that is desirable in a world turned strange with captivity). All that had defined my life was ripped away, a consequence of my own choices—yes. Does that make it any less traumatizing—no, no it doesn’t. After a year in county jail, the 3 a.m. wake up, the shackles and belly chains, the indelible sentence, being pulled further into the unknown. Alone.

Getting to the new hell, learning the insanity firsthand and all the inevitable lessons of what to do and not do, while leaving the expectations of logic far behind. Striving to be invisible. An anonymous automaton in the herd. While quietly forging the only thing that can keep you human: relationships with other humans.

Five years later, they begin to leave.

I remember seeing someone sobbing, hearing them say, “I’m not making friends with any more short timers. I’m not. I can’t keep doing this.”

I didn’t understand, until then I did.

First, Nayeli left. And that was hard. We knew she was leaving. Scheduled to be deported back to Mexico when she reached the end of her sentence. She was working at the chapel. We tried not to talk about it. We couldn’t, not without crying. How do you lose someone who has been your best friend? Gone through the worst of hell with you? Experienced all the grief, heartbreak, hardship and dehumanization as you and through it all stayed a light in the darkness. Stayed human. Helped show you what hope looks like. Hope which is a hard won commodity and becomes less obtainable in direct proportion with the increasing length of one’s sentence.

I thought my 18-year sentence was immutably hopeless until I saw a 30-year sentence, a life sentence, life without parole. My own hopelessness diminished considerably—in comparison to the dust of their hope.

I was working at property. She brought the few things she would be taking. I saw her dressed in real clothes, not a shapeless prison uniform. A blue striped shirt, dark skinny jeans.

Nothing she would have chosen. Laughably unfashionable except for our inability to laugh. We

were able to pray together–a consolation amidst the desolation. Hollow grief. Familiar again, the worst of friends returned.

Then I understood, and the next year, Sophia left. Then Ashley, the year after that. Angelina left this past September and I left in October. All of my short-timer friends gone and then my turn to leave. Which takes me back to the next point. Being the one ripped away. I have cultivated the belief that the ones who leave suffer a type of survivor’s guilt and I don’t believe I’m wrong.

The institution itself discourages contact between the released and the incarcerated, changing the policy from 90 days no contact to 3 years no contact (by mail anyway—they can’t police the phone calls but the phone calls cost a lot more money than a stamp). There are ways and ways around it, of course, but it becomes a hassle. Pictures get caught up and have to be returned. Letters not sent by the person recruited to be the go-between from facility to facility. It all conspires to extinguish the ties formed during incarceration. But it doesn’t. No matter how many restrictions on contact or whatever loss of contact occurs, it cannot and does not directly affect the emotional bond forged between humans. It only helps to further traumatize and deprive that human of the relational support they’ve developed during a time and at a time when love, compassion, and common ground are a scarcity, at best.

It is hard to abandon those you have suffered with, those you love. When you are ripped away from them by forces beyond your control—and have been abandoned time and time again yourself by the same unrelenting circumstances–you feel doubly bound to win through the obstacles and stay faithful to these friends so precious, so hard won.

It is not uncommon for those in prison to forge their own familial ties and designations within the bounds of their carceral experience. Many having lost (through time, distance or choices) their own children, parents, or other family members form new cohesive groups of family on the inside. Kids, moms, aunts, sisters, and even dads and uncles now cling together in a fragile network of relationships founded in mutual loss and hardship. Subject to dissolution upon transfers or release. Making every freedom won an equal measure of loss.

Making sure, even in the victory of discharge, you lose everything, yet again. Always alone. Forced to leave behind the only emotional support you have had for years and knowing that some of the people you have left behind are not able to leave themselves for many years. Sometimes they never will.

How do you process this? How do you just forget about the people who have loved you, laughed with you, cried with you, cheered for your successes, commiserated your disappointments? Especially when those left behind are just as deserving or even more so, of a second chance, of leaving prison, or at least moving forward? There’s no winning. There’s no happy ending. You can’t stay and you don’t want to. But you don’t want to leave them there either. And you don’t get to choose. You just have to go.

Heart sore and no help for it, I throw back the blanket and get up to pack.

Purchase Variations on an Undisclosed Location: 2022 Prison Writing Awards Anthology here.