Yet another intense meeting hastily convened. The topic – the content in our monthly newsletter to our incarcerated community. The worry – would any of the newsletter content get our collective project, or more crucially, the people we work alongside in prison, sanctioned?

This month’s snail mail newsletter includes short articles about water quality testing (the deadly Legionaries disease is present in the Illinois state prison system), hunger strikes by incarcerated people at Riker’s Island Jail, Illinois’s guard’s low rates of COVID vaccinations, and New Jersey’s prison population reduction. While readily available outside prison walls, this news might inflame prison staff with unpredictable consequences. What will get us kicked out or get our inside people transferred to a different prison or sent to any form of solitary confinement?

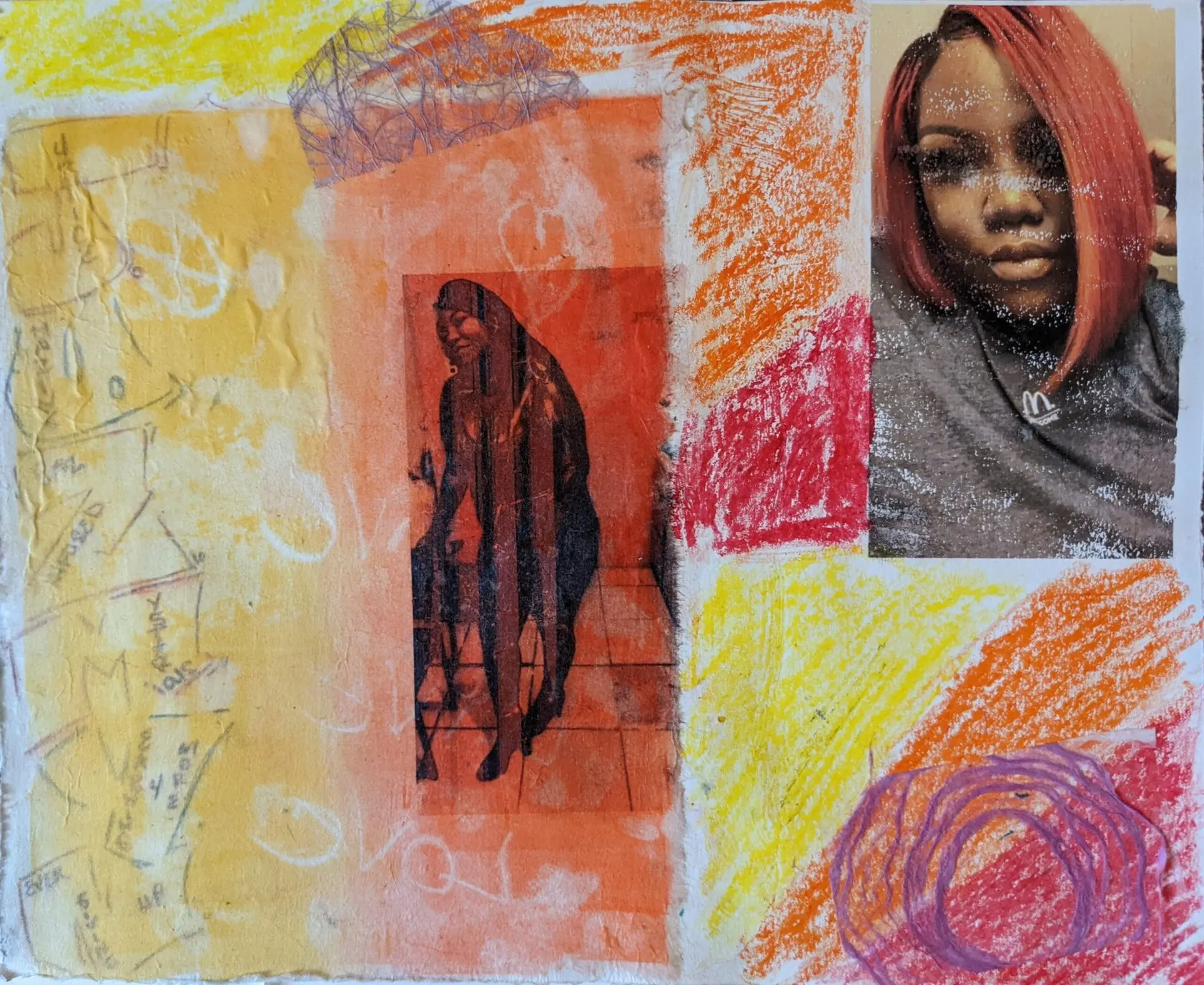

As we strive to advance an abolitionist politic – or to end our reliance on policing and prisons – this was a familiar debate highlighting how prisons are held together as much by ideas and beliefs as by steel and concrete. Struggles against prison censorship remind us that information is power and that prisons maintain their power, in part, by preventing the spread of dangerous ideas. Our goal has never been simply to ensure that people inside get access to free books and courses (who wants a world where the only free college classes/degrees or books or art-making workshops are in prison?). Rather, if abolition requires us to change everything, books, education, and art-making are key revolutionary tools.

Yet as deft as we have grown in anticipating and parsing the logic of the prison, worrisome skills to develop, we are still often wrong: We sent the newsletter in as is, and nary a ripple.

We are well schooled: For those coming in from outside to teach, censorship of all kinds is a daily negotiation at the prison. While the state has a list of banned print materials and the prison has a formal process to get books “approved,”– these official routes are just the beginning. Examples of “arbitrary and irrational” denials abound: even though a book was formally cleared, we had to rip out a page as a guard randomly flipped through this book and spied an image of a tiny map of 18th century Europe; “all the racial stuff” – including books by W.E.B. DuBois and Frederick Douglass – were barred entry to another prison in Illinois; last year anything that appeared to be critical of policing – even abstract historical and scholarly materials – was summarily denied. Most perniciously, materials that suggest “fraternization” – an impossibly slippery term that includes a card created by inside folks acknowledging your parent’s death – triggers the prison to revoke outsiders’ access and has sent inside folks into extended 24-hour lockdowns.

Of course, it is not only books that are censored. In many states, the only items that can be mailed to prison must be purchased from a list of “approved” vendors (who make a tidy profit). (The increased reliance on tablets and e-books in prison easily facilitates surveillance and profit for private corporations, for example, one company charges by the minute to read e-books). Letters – USPS correspondence – is always under threat: some jurisdictions only accept postcards and photocopies of the original letter.

And our experiences are only the tiniest fraction of what is endured both by other visitors to the prison (most often mothers/sisters/daughters and lovers) and those incarcerated.

Yet prisons are hardly the only place in the US where books are policed, surveilled, and restricted. The American Library Association reported an “unprecedented” number of attempts to ban books – particularly for queer themes – across K-12 schools in 2021: All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, a queer black “memoir-manifesto” earned the dubious honor of 2021’s most contested book. Beyond book bans, public schools lack libraries and librarians: In 2022, only 90 of Chicago’s 513 public schools employed a full-time librarian. (And engineered scarcity does not only apply to librarians and books: one in four students in the US experiences “period poverty”- no access at their school to necessary menstrual products).

As educators and learners, we want All Boys Aren’t Blue, 18th-century maps, W.E.B. DuBois, and menstrual products freely circulating in all classrooms and libraries (in the majority of US state prisons, menstrual products are only often available for a hefty fee). Access to life materials must be redistributed. But this should not be an end goal.

Our work must also challenge and dismantle the very conditions that make this brutal and grotesque arrangement of power imaginable in the first place. Our work for freedom must support the creation of a world where prisons, and bans on trans lives, are impossible.

Yes – the struggles at the prison site and the public classroom site are not parallel, but they are intertwined, and solidarity is crucial in our organizing and analysis. Arresting book bans in prisons, and ending our reliance on a carceral state, will be infinitely more imaginable and feasible by strengthening struggles across sites and institutions that might appear disconnected, and disparate. “There is no thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives,” as Black lesbian feminist poet Audre Lorde astutely reminds us. Our campaigns are stronger if people in prison demand that all middle school students can read All Boys Aren’t Blue and if those in high schools demand that incarcerated people can access Policing the Planet. And beyond campaigns, our movements for freedom are stronger if incarcerated people organize for police-free public K-12 schools and middle schoolers learn about transformative justice and argue that our carceral system does not offer accountability or justice.

We can and must do at least two things at once – push for the circulation of materials/redistribution of resources in all of our classrooms AND build and strengthen dialogues and organizing between sites and struggles. These interconnections create possibilities for wholesale transformation and build the communities we need.

As the prison industrial complex is vast, and as we must “change everything” as Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us, the good news is that there are many sites for resistance and engagement.

What to do? Get informed and active about organizing that shrinks our reliance on carceral – or punitive – systems and structures. Buy and/or share copies of radical books for people inside and outside: Join and/or support one of the many books to people in prison projects or incarcerated people correspondence initiatives, like Black & Pink. Redistribute the resources – books, money, power. Wade into the messy praxis of engaging, transformative justice.

If you are a student or a worker in a classroom – demand that your institution remove questions from their employment and application forms that ask about criminal records histories and develop (or strengthen) your public institution’s ability to meet the needs of systems-impacted people. Demand your library carry every contested book and organize pop-up study and reading groups. Engage abolition at the site of your K-12 school or college/university. Organize for free post-secondary education – a reality in other nation-states.

Dismantling censorship in prisons and classrooms is a necessary but not sufficient part of the work to build flourishing communities where art and education are for everyone, everywhere. Now!