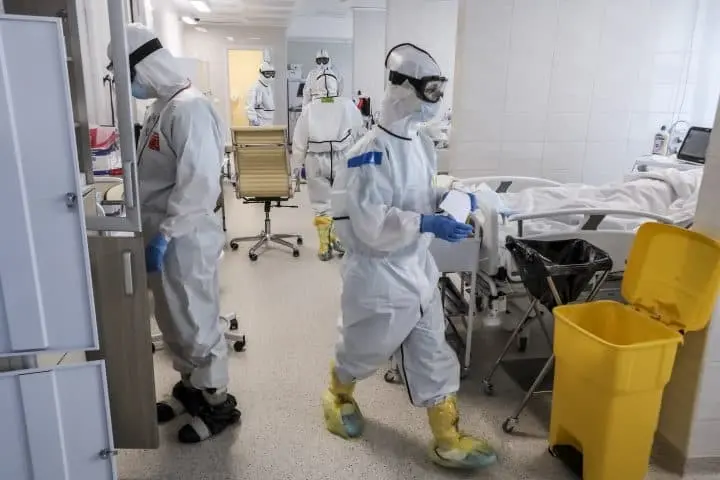

On May 31, police raided a Ugandan LGBTQ+ shelter, arresting 44 people and charging them with “negligent acts likely to spread infection of disease.” Authorities also leaked video footage of the arrested individuals online, essentially outing them in a country where being gay can get you murdered.

It’s part of a COVID-19 pattern in Uganda, where LGBTQ+ individuals continue to face harassment and aggression from security forces and others both online and in person.

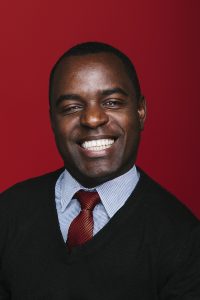

Speaking out on their behalf: Frank Mugisha, a prominent Ugandan advocate for the rights of LGBTQ+ people, who played a critical role in advocating for the 44 people arrested in May, helping to secure their release and compel the government to drop all charges. A longtime organizer, Mugisha is the founder of Icebreakers Uganda, a support network for LGBTQ+ Ugandans, and is executive director of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG), the largest LGBTQ+ organization in Uganda. Mugisha is a recipient of the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award, the Rafto Prize, the International Human Rights Film Award at Cinema for Peace, and has been recognized by the United Nations as a human rights defender. In 2014, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Despite death threats and harassment, Mugisha continues his brave work.

Speaking out on their behalf: Frank Mugisha, a prominent Ugandan advocate for the rights of LGBTQ+ people, who played a critical role in advocating for the 44 people arrested in May, helping to secure their release and compel the government to drop all charges. A longtime organizer, Mugisha is the founder of Icebreakers Uganda, a support network for LGBTQ+ Ugandans, and is executive director of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG), the largest LGBTQ+ organization in Uganda. Mugisha is a recipient of the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award, the Rafto Prize, the International Human Rights Film Award at Cinema for Peace, and has been recognized by the United Nations as a human rights defender. In 2014, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. Despite death threats and harassment, Mugisha continues his brave work.

PEN America worked with a local partner to interview Mugisha regarding the state of free expression for the Ugandan LGBTQ+ community during the pandemic and in the wake of this year’s elections. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What does it mean to live in Uganda as a LGBTQ+ person today?

Living in Uganda as a LGBTQI person today—or let’s say, if you are perceived to be LGBTQI—it’s very high risk because you don’t know when you are going to be prosecuted, persecuted, or violated. For an activist like myself, that means I have to really be very careful because I could get arrested for my advocacy. I could get blackmailed or extorted by the police, or attacked by people who are extremely conservative and homophobic as I go about my ordinary life.

For LGBTQI people who are not out, there is a lot of fear that they could get outed by the media. And usually we’ve seen when people get outed, they suffer so much social exclusion. Some people have lost their jobs, or their families have thrown them out. There’s also great fear and psychological trauma that people suffer when they are in the closet and fear being outed.

I would say the transgender community suffers the most violations in Uganda. As long as someone does not really look how society wants them to look, they will be targeted.

“Living in Uganda as a LGBTQI person today—or let’s say, if you are perceived to be LGBTQI—it’s very high risk because you don’t know when you are going to be prosecuted, persecuted, or violated.”

How do you think the COVID-19 pandemic has most impacted the LGBTQ+ community in Uganda?

The impact from COVID-19 has been profound. Many LGBTQI people, like most Ugandans, depend on working on an everyday basis to find sustainable means of living. With COVID-19 and the lockdown, many LGBTQI people ran out of employment and ways of making money to sustain themselves. Some people had to resort to living in shelters or staying with friends, and other people had to go back home. For the majority of LGBTQI people who went back home, they went into very toxic family relationships, where some of them are not so welcome because of who they are and have to conform to who their families want them to be. This means they couldn’t see their partners anymore, or for transgender people, it means that they have had to dress the way they are expected to dress, not how they feel comfortable dressing.

The issue of mental health and trauma has also been a very big issue during the pandemic. That’s what we’re dealing with most right now at SMUG—we are trying to support the recovery and give a lot of mental health support to the LGBTQI community.

Throughout the pandemic, we’ve also seen cases of people being harassed or attacked and blamed for COVID.

Has the government’s blocking of the internet and ongoing blocking of Facebook affected the visibility and free expression of LGBTQ+ Ugandans?

Yes, social media has been very important for the LGBTQI community, especially in creating a sense of security. For me, being LGBTQI and living in Uganda, sometimes people wonder, how do I survive as an openly gay person? Well, I know that part of my security is social media because if anything happens to me, such as getting arrested, then there’s going to be all these hashtags, such as #FreeFrank, and definitely the government will listen to that.

Around the elections in November, when a majority of civil society leaders were getting arrested, [Ugandan] President [Yoweri] Musevni himself said, the “operation” of this resistance is being funded by homosexuals. It puts me at the center of whatever was going on between the opposition and the ruling party. When the internet was shut off, that had been the thing I was worried about most for my security. When that happened, there was no rescue in case something happened.

“Social media has also been essential for solidarity with the LGBTQI community both inside and outside of Uganda. It allows us to tell our own stories.”

Social media has also been essential for solidarity with the LGBTQI community both inside and outside of Uganda. It allows us to tell our own stories. We can’t tell our own stories in the mainstream media. The media in Uganda is very aggressive toward the LGBTQI community. But even those that are not aggressive, they are silent. They can’t, for example, write an article about me or my work. Because some of them, of course, are homophobic and very conservative, but then some of them are also worried about the government directive not to publish LGBTQI stories, negative or positive. Or they are worried about how the government will react, or the Uganda Communications Commission, if they publish a positive story about an LGBTQI person. So we are left with social media to talk and tell our stories.

When the 44 got arrested, we were able to know about this through social media. While it was the second biggest story in Uganda at the moment, news outlets didn’t report about it at all! So the mainstream media is selective and sometimes really scared. And of course Facebook is accessible for many of our constituency members, and many of them use Facebook to speak to their own colleagues in other countries, or even to find LGBTQI friends or partners.

Have some people been harassed online?

Yes, there’s a lot of that. Especially when there is anything posted on social media about homosexuality that is personalized. For example, if someone puts up a picture of someone and says they are gay, they definitely are going to receive a lot of hate speech or a lot of harassment or even threats. I myself have received a lot of threats, and there are many people, including celebrities, who are known or perceived to be LGBTQI who have also received a lot of threats and harassment on social media.

The most aggressive harassment I received, and that caused a lot of fear for me, was during the elections. There was a famous blogger who posted a picture of me and linked me up to the opposition. I received a lot of threats, including death threats, and some of them were even on the phone. People would call me and threaten me.

“Always look out for help. The worst is to remain in isolation because that mentally can deeply affect you. Navigate it slowly, sensitively, but at least talk to someone about it, or be open to someone about it.”

Could you say more about censorship and self-censorship here in terms of LGBTQ+ content?

That is one of the biggest problems we have. In Uganda, when it comes to issues related to the LGBTQI community, many media people do not bother even talking to an LGBTQI person to understand their side of the story or their opinion. The media just writes their own story and disregards the opinion of the LGBTQI community. Most of the stories are one-sided. There have been major issues here when the LGBTQ community has been affected so much, but then you see that most of the reporting is only negative and one-sided. Or it’s not reported at all.

Media houses are so sensitive because of the Uganda Communications Commission controlling the content, but also some media houses are equally very conservative and very homophobic and transphobic, so they would rather not cover anything on LGBTQI people.

What are some of the deepest worries of LGBTQ+ people following the parliament’s passing of the Sexual Offenses Bill, a piece of legislation that would criminalize consensual same-sex acts?

The biggest worry is if the president signs it into law. In a period of less than one year, two shelters [for LGBTQI people] have been rounded up, raided by the police, and people arrested. So that means if this law is passed, it weaponizes the police more and gives more power to law enforcers to harass and persecute LGBTQI people.

In Uganda, there’s also people that decide to take the law into their own hands. So we have seen a lot of violence and mob justice toward the LGBTQI community. Because of this bill, the media is definitely going to cover the illegality of homosexuality further. Then this starts weaponizing Ugandans more to keep reporting to authorities any persons known or perceived to be LGBTQI and for authorities to act and arrest people, but also for increased blackmail and extortion. This then perpetuates the fear LGBTQI people have to access services, since they fear they’ll be arrested. So right now, it is really so scary.

“One of the best things that a young person can do is to be themselves. . . . I was once a young person myself who came out of the closet. So I want to share my own experience and say, ‘Look, you can use this experience to navigate your sexuality and also still remain in society, remain in school and get good grades, and work and build your career.’ I want them to know that they can be Ugandan and still be LGBT.”

Would you mind sharing briefly about the work you are doing with SMUG?

Our work is primarily around advocacy and raising awareness for the LGBTQI community. For example, with the 44 people that were arrested in May, we tried to raise awareness around that, and through education, change the hearts and minds of Ugandans to actually accept and live tolerantly with the LGBTQI community. That includes trainings with the police, the judiciary, local councils, and even Boda Boda Riders, so that they can live with LGBTQI people without harming them. We also provide safety and protection services for the LGBTQI community, including legal support if someone is arrested or alternative housing if someone is thrown out of their village or home.

We also provide basic information on human rights, so that if people get arrested, they know how to represent themselves and respond. We also provide social support and sometimes aid when someone is arrested or beaten. We publish reports and studies every year on violations of the LGBTQI community and do a lot of work with other partner LGBTQI groups in Africa and internationally.

Are there any pieces of advice or resources you suggest for younger LGBTQ+ individuals attempting to navigate Ugandan society?

One of the best things that a young person can do is to be themselves. But given that Ugandan society is very hostile, young people must navigate it sensitively. Someone just has to go on the website and search, because the internet is very rich with a lot of information. At SMUG, we have available sources and references that we provide for any person depending on their sexuality. Always look out for help. The worst is to remain in isolation because that mentally can deeply affect you. Navigate it slowly, sensitively, but at least talk to someone about it, or be open to someone about it.

I was once a young person myself who came out of the closet. So I want to share my own experience and say, “Look, you can use this experience to navigate your sexuality and also still remain in society, remain in school and get good grades, and work and build your career.” I want them to know that they can be Ugandan and still be LGBT.