“Promoting homosexuality is forbidden! We’re telling you, this is just the beginning! We’ve warned you a hundred times!”

These chilling words are heard in a video circulating on social media, showing a mob of men surrounding a bar hosting a drag show in Lebanon’s capital Beirut. The men, who were members of the right-wing Christian group “Soldiers of God,” assaulted patrons outside the bar and besieged it for nearly an hour on August 23, forcing the organizers to cancel the show.

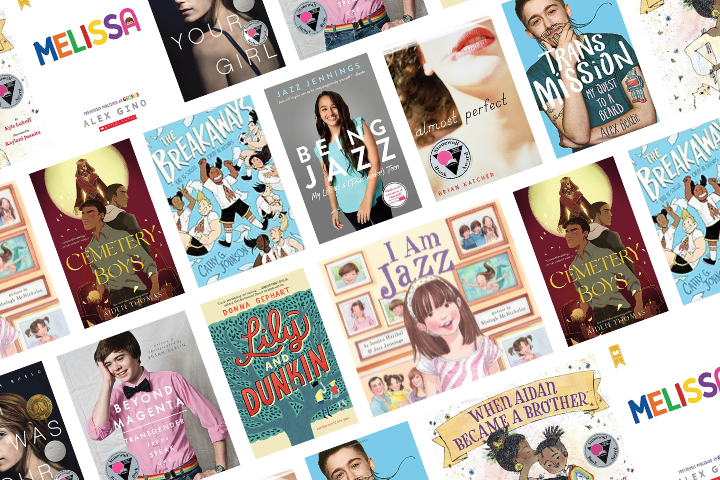

The incident is a harrowing example of a broader assault on LGBTQ+ rights and expression in Lebanon, where Pride marches have repeatedly been met with threats and official harassment, and last year Lebanon’s interior ministry announced it would bar all events that promoted what it called “sexual perversion.” Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in July gave a speech calling for LGBTQ+ people to be killed, and the government has since ridden the wave of hate speech with actions that veer into farce, banning everything from children’s books to the game Snakes and Ladders to the film Barbie –– all under the umbrella of supposedly combating immorality. Indeed, Lebanon’s minister of culture reportedly responded to the attack on the drag show by asking why security forces had not shut down the performance to begin with.

The anti-LGBTQ+ campaign in Lebanon reflects a larger trend of attacks on free expression in the country: just this week a stand-up comedian was detained for a joke made five years ago, and journalists facing interrogations and prison sentences for their work. Many observers see Lebanese authorities’ crackdown on LGBTQ+ activists, journalists, and comedians as a broader attempt to scapegoat marginalized communities in the face of sustained popular anger at the government for corruption, misrule, and a lack of justice for the devastating 2020 port explosion.

Though the attempt by Lebanon’s political and religious leaders to muzzle critics and marginalized communities uniquely reflects the country’s current circumstances, it is also indicative of a regional trend of authorities combining hate speech with vague laws targeting amorphous crimes to go after LGBTQ+ communities –– and eventually, journalists, satirists, and a wide range of writing and expression. In many cases, the laws contain language remarkably similar to that used by the mob that attacked the drag show. And while opaque laws prohibiting conduct that supposedly “promotes immorality” may not gain as much attention as a gang screaming about “promoting homosexuality,” the impact is often more insidious and far reaching: authorities use them to target not only the LGBTQ+ community, but a broad range of marginalized groups, and to strip them of a broad range of rights beyond free expression.

At around the same time Jordanian King Abdullah II signed into law a new version of the country’s cybercrimes law that stipulates prison time for “promoting, instigating, aiding or inciting immorality” – despite widespread objections from local and international advocacy groups, including PEN America – the Iraqi parliament introduced their own version of a draconian cybercrimes bill which, if passed, stipulates prison sentences for “inciting armed disobedience,” promoting “immorality or indecent content,” or “attack(ing) religious, moral, family, or social principles” online.

Any laws that punish online activity with prison time for such vaguely worded offenses present a clear attack on freedom of expression. But the bundling of “immorality” together with “armed rebellion” points to a more sinister end: equating speech or writing that assert viewpoints or identities outside the cultural mainstream with terrorism or sedition. And this trend is dovetailing with another worrying one in the region: a campaign of state-sponsored incitement, harassment, and legal crackdowns against LGBTQ+ communities.

LGBTQ+ advocates in Jordan have been highlighting this convergence, pointing out the language in the revised Jordanian cybercrimes law’ that could be weaponized against the community — and the fact that proponents of the bill have explicitly acknowledged this as an aim — and contextualizing it within an ongoing campaign of government harassment of LGBTQ+ activists and organizations. But recent arrests and sentences in Jordan have also shown how the government has already targeted a range of writing. Earlier this month, satirical writer Ahmed Hassan al-Zoubi was sentenced to one year in prison for a Facebook post criticizing the government’s response to fuel price protests that allegedly provoked “sectarian strife.” And a few days later, the journalist Heba Abu Taha was briefly detained after she was sentenced to three months in prison for a Facebook post criticizing Jordan’s relationship with Israel; she was released pending appeal. By cracking down on dissent and LGBTQ+ identity with vague charges, the Jordanian government is able to stifle potential dissent in the kingdom.

This convergence is also happening in Iraq, where armed militias have long targeted members of the LGBTQ+ community with brutal violence. Earlier this month, the Iraqi Communications and Media Commission, the country’s media regulator, issued an order banning use of the words “gender” and “homosexuality” in media and on social media –– and stipulates the use of “sexual deviancy” in place of “homosexuality.” A week later, an Iraqi member of parliament introduced a new bill that would punish same-sex activity with the death penalty or life in prison, “promoting homosexuality” with seven years in prison, and “imitating a woman” with three years in prison. The proposed legislation, startling in its brazenness and cruelty, comes after Iraqi cleric Muqtada al-Sadr started a campaign late last year against Iraq’s LGBTQ+ community.

The crackdown emanating from Baghdad echoes a parallel campaign in Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region, where LGBTQ+ people have long been marginalized and targeted with hate speech, if not arrested outright for “undermining public morality.” During Pride Month this year a court shuttered the Kurdish LGBTQ+ advocacy organization Rasan in response to a suit filed by a member of Iraqi Kurdistan’s parliament accusing the organization of “promoting homosexuality” and violating “public morality” –– with the judge justifying the order by citing the group’s rainbow-colored logo. Notably, Iraqi Kurdistan has been witnessing an intensifying crackdown on journalists and press freedom over the same period, and a law passed in 2008 ostensibly to combat gender-based violence and online abuse has since been weaponized against dissent.

These are some examples, but there are many more: Turkish authorities violently targeting Pride events while pushing nebulous laws against “disinformation,” and Egyptian authorities using social media and dating apps to go after LGBTQ+ people. The repeated bans against Lebanese rock band Mashrou Leila, whose support of LGBTQ+ rights resulted in their performances being banned in Jordan and Lebanon, while a concert in Egypt resulted in a wide-ranging crackdown on LGBTQ+ people. Ultimately, the band broke up.

The attacks against LGBTQ+ expression in Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and across the Middle East all stem from specific political contexts and histories, but they won’t stop with these communities, nor will they respect borders. In the US, attacks and bans on drag shows are part of a larger effort to restrict LGBTQ+ expression, and Ugandan authorities have effectively criminalized the expression of LGBTQ identity, while a deepening crackdown in Hungary is now netting booksellers. If speech advocates don’t call out such trends for what they are, more and more countries are going to see censorship and intimidation efforts that start with LGBTQ+ communities but don’t stop with them. And all writers and activists, regardless of their identities, may eventually find that they’re the targets.