Turning Sentences Around

The clerk of the prison’s college computer lab handed me a book. Normally, he only handed me new college books every semester. He knew I took the art and craft of writing seriously, so he wouldn’t recommend I read a craft book that I’d feel was a waste of my time.

But this one was different. On the cover were images of envelopes with prison return addresses, cut into the shape of butterflies. I thought it was aesthetically dope. It spoke to the genesis of my metamorphic period—trying to become something, someone, more than prisoner, killer.

Earlier in my bid, I came across PEN America’s original guide, The Handbook for Writers In Prison, a slender 120-page booklet. I was talking to a guy in the cell adjacent mine about how I wrote poetry, and one day planned on writing a book. He stuck his hand out between the bars and showed me The Handbook. “Here. You should use it.” At the time, a true novice, I appreciated that it laid out the basic mechanics of grammar, explained the different forms of writing, and included the how-to process of submitting manuscripts and copyrighting work.

In 2022, that instructional booklet was revamped into what the computer lab clerk had placed in my hands—The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting a Writer’s Life in Prison. I liked it way more than the original; it brimmed with resources, names of different organizations, publications, and included essays by currently and formerly incarcerated writers.

Like the butterflies, the book’s double entendre in the title rang true for me. Back in 2010, if the judge hadn’t handed me 25 years for manslaughter, I doubt I’d be who I am today: a guy in prison, serving a long sentence, trying to be a writer.

Over a decade ago, I hounded second-semester Bard students for edits, even convinced a daring buddy to sneak a short story to one of his professors. I permanently borrowed their style guides and English class handouts. I read every craft book on writing fiction I could get my hands on. I submitted pieces to literary magazines, just to receive “thank-you-for-your-submission” slips in the mail. First, I took each rejection personally. Do they know how many hours of yard time I lost? Do they know how many cigarettes I chain-smoked? How many black cups of instant coffee I drank—and spilled—on drafts?

Reginald Dwayne Betts’s introduction to Sentences expressed why I picked up a pen in the state pen in the first place: “There are not many things people can become while in prison that garners the public’s respect. Even for those coming inside with skills, the opportunities to make use of them are scarce….And then, there is the writer.”

I paused, chewed on a pen cap, digested what he said. When you think prisoner, you think squanderer of opportunity. You think disenfranchisement. Dehumanization. Disgrace.

It wasn’t always like that. Before my incarceration, I had a budding career. I rapped, produced, engineered. I was respected and loved in my neighborhood. But how far I’ve fallen. Now in prison, wrapped in a wall, I asked myself: How does a prisoner rise from the thick of disgrace?

The clerk didn’t let me keep his copy. “If you write to PEN America, they’ll send you one for free.” So I did.

Weeks later, I was called to the package room to pick it up. That evening, I took a shower and locked back in. Guys argued and blasted Lil’ Durk in the cellblock, so I stuffed in my earplugs and grabbed my highlighter.

Wilbert Rideau, who made it off of Angola’s death row, became an editor and publisher of the Angolite, the award-winning prisoner-run newsmagazine. Rideau leveraged his talent to amass a network that helped get his sentence judicially commuted. I slid a yellow highlighter over a few lines: “Writing is rich with promise, and potential. You never know who’s reading you….Had I not become a writer…the editor of a magazine, had I not done everything in the public eye, where I could be seen and judged, I would still be in prison.”

Saint James Harris Wood described an unorthodox strategy. He hammered out a monthly stream-of-consciousness rant letter about prison, made numerous copies, and shot it off to a slew of magazines. Once Esquire and The Sun Magazine bought the letters, other magazines began following suit.

Piper Kerman dropped a few jewels on seeing our current situation as an asset. “One of the most compelling ingredients of writing is conflict, and incarcerated people are pretty much guaranteed to have that, in spades.” Piper spun a one-year prison sentence into Orange Is The New Black, a memoir that was later adapted into a Netflix series.

It felt like a shot in the gut when Thomas Bartlett Whitaker dismissed the idea of guys making any real money as prison writers. But John J. Lennon turned that on its head. He told us how he was making money and landing stories in Sports Illustrated and Esquire. Who was this guy?

John’s bio read that he was still locked up in New York. He was in Sullivan Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in the Catskill Mountains, not far from Shawangunk, the max joint where I was serving time. As serendipity would have it, in August 2022, I found myself on an unplanned lateral transfer to Sullivan.

In prison, we marginalize one another without even realizing it. We all wear green, and it’s easy to assume that the next guy doesn’t have a whole lot to offer. But here was a guy in prison who’d made a career for himself. It was inspiring. In a way, the book helped me see beyond the prison culture of status, which reveres shot callers who commit violence and smuggle drugs. It gave a more righteous status to a guy who became a real writer, a prisoner who’d risen from disgrace.

When you land in a new prison, you’re usually looking for familiar old faces, maybe somebody you know from a previous joint. Somebody with a reputation who can describe the lay of the land. Guys who want to get high soon learn who has the shit. Gang members seek out their people and pay homage—make sure they’re not on the hit list, or no one’s on their hit list. (I should know; I’m a mason now, but I used to be blood.) When I arrived at Sullivan, I asked the first prisoner I saw in the intake area if he knew John J. Lennon. He blinked hard from behind his specks, and said, “Yeah, he’s in my block.”

I sent word with almost ten people for John to meet me outside. It took about four days before we met. He strolled out to the recreational yard in sweats, running sneakers, and an Under Armour shirt. The sun glinted off of his Nike shades. I walked up, thinking that he might be too arrogant or self-absorbed to speak with me. That’s what somebody had said about him. But the instant we started talking about writing, he opened right up. It was then that I, unknowingly, signed up for Lennon’s masterclass.

Days later, I’d brought out a manilla folder containing a few college essays and other pieces of fiction. He said he’d take a look after a deadline for a piece he was writing for the Real Estate section in the Sunday edition of The New York Times.

I wanted to be shown how to improve my work; I didn’t want the head-patting praise professors tend to give students in prison college programs. I get it; they want to validate their students, not discourage them. Some people need that type of encouragement. But John wasn’t into that. He was going to hold me to the highest standard.

A week later, we stood by the pull-up bar in the yard where guys loitered, and John handed me back the folder. I had a natural voice, he told me, but I need to lose the over-confidence and familiarity with my tone and learn structure. And to him, anyone who wrote fiction in prison was squandering an opportunity. The most publishable work is journalistic, he said, and I could open any magazine and see how much ink is nonfiction versus fiction. Plus, there was so much material in this place.

As we walked, he made a quick lift of his chin to the shit talkers pumping weights, the gray-chested sunbathers chuckling, the mentally-ill man picking up cigarette butts off the blacktop. He explained how the story was all around us and within us, and in order to find it I’d have to seek it out—it’s out here, in the cellblock, out in the yard. I just had to engage people in conversation. Be curious. That’s journalism.

Prison breeds unhealthy antisocial behavior—gang members mostly stick to themselves and the Spanish speakers click up. West Indians, too. In order to be a journalist, I had to break the subculture norm holding us here, keeping us separated.

John taught me what he did. I read all his work. He explained how to turn sentences around, reverse engineer good writing. He walked me through the process of what he does, memoir meshed with journalism. I learned the lingo: nutgraph, scenes, digression, kicker, bookend, explanatory structure.

I think it was shame that made me run from writing about prison for so long. I used pseudonyms, ranted about injustices on paper, and hid behind fiction. I wanted readers to lose themselves in my stories, so maybe when they learned that I was a criminal, on account of my talent, “I could speak of the darkest cage and still people would not hear prison[er],” as Justin Rovillos Monson writes in an essay in Sentences.

Reading John’s work—where he grapples with remorse and humbly accepts both identities of murderer and writer—opened my eyes. Working with him gradually gave me courage to wrestle with my own wrongs on paper. The Department of Corrections doesn’t help us come to terms. John suggests that in Sentences—to come clean about our crimes. It’s how we become a more trustworthy narrator. For me, that was hard to do. I killed someone I loved. Living with that is a fucked up feeling. Writing about it makes me ashamed.

As the seasons changed, guys brought out hats, scarves, and gloves to the yard. They brought tobacco and rolling paper, Black & Milds to roll up weed, and crudely fashioned plexiglass icepicks. I brought a composition notebook and a pen to jot down John’s words. We talked as we walked the perimeter of the blacktop to keep warm. Sometimes, I’d stop, flip back the cover, hold the notebook on one hand, snatch the pen, and scribble wisdom. “I don’t go into a story with a theme already baked in. What I mean is, I may have an idea of what I want to write, but character drives story. It’s only after I learn my character that I understand the story I want to tell.”

I learned that access was my edge over other journalists. John explained the power of scenic writing. Most reporters who write about prison from outside must reconstruct scenes described by their subjects, but the prison writer can write first-hand scenes.

That same month, I started a piece about my friend who overdosed in another prison, and how his death forced me to own my history with substance abuse. We sat at a stone table, under a dreary December sky. John handed back edits of my fourth draft. I was tired of rewriting, and just wanted to be published already. He then pulled out an aggressive edit from one of his editors. It was eight pages whittled down to four. He was hard on me for a reason.

“It’s a dance. It’s the relationship between editor and writer. It’s a back and forth. Editors are smarter than us. They understand story better. They pull out the best in us, and that’s what gets left on the page.”

As I wrote this essay, I thought about how prison, if we let it, can bring out the worst in us. It’s a warzone, a psych ward, a shelter, a trap house. What if whatever character and work ethic John had learned from working with his editors in their many back and forths was being transferred to me? Would journalism, writing stories about others, teach me a higher form of empathy?

In May 2023, The Prison Journalism Project published my essay, “In Prison, The Networks of Addiction Run Deep.” In it, I memorialized my friend. I can thank John for that, working with me through two months and six drafts to complete my first published piece.

Looking back, I see that those early rejection slips were the licks I had to take in the learning process, each one was another challenge, a message, a wake-up call that said get back up and grind little homie. Everyone loves a comeback story.

When I first got to Sullivan I didn’t have any pieces published. Until I received a guiding light in the form of a book in the computer lab that day, I still felt buried. Even today, I look at the cover and imagine wings lifting from the page, fluttering around and above me. The Sentences That Create Us blueprinted how others rose from disgrace. It’s how I’ll rise from disgrace. Call it the butterfly effect.

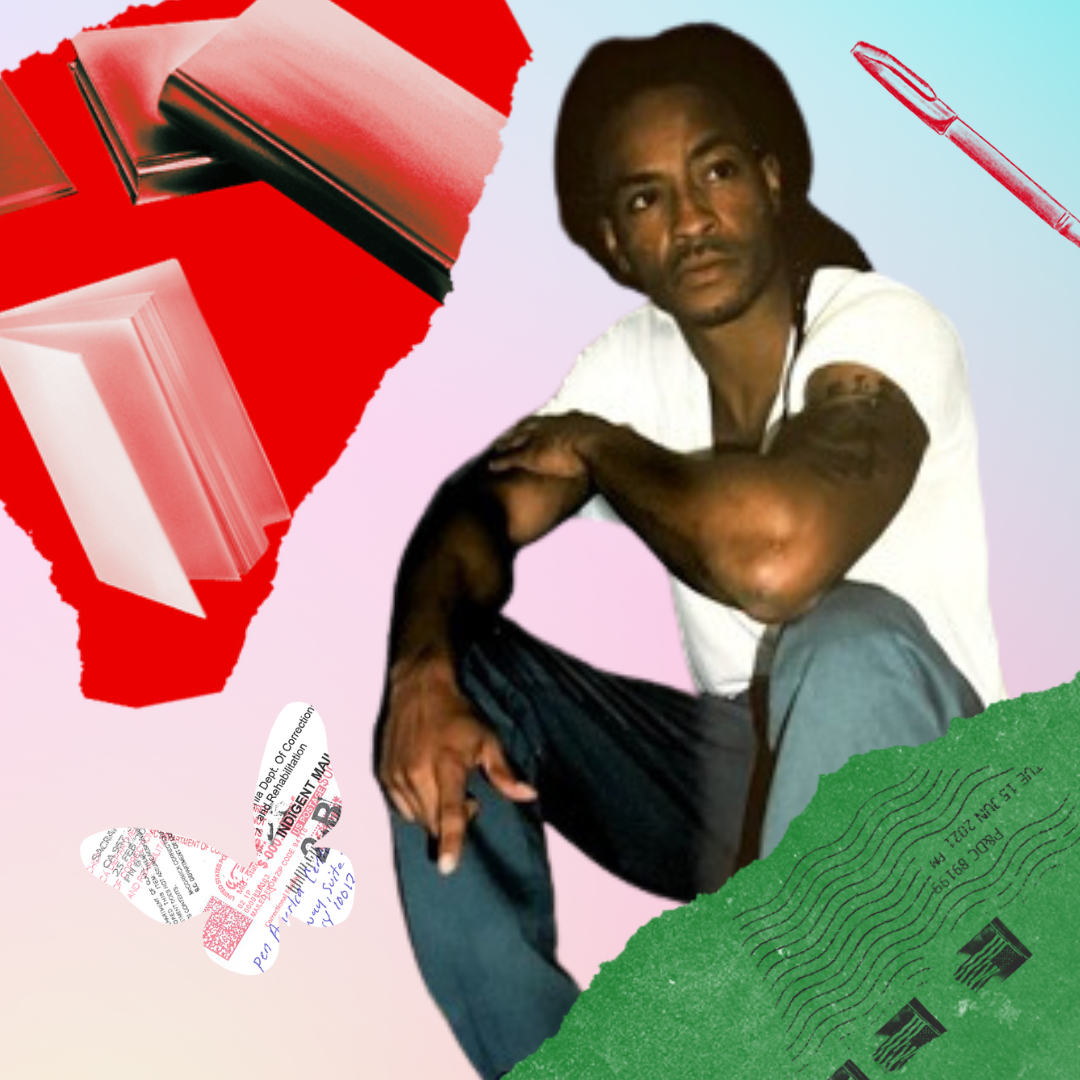

Robert Lee Williams is an incarcerated writer in New York. His work has been previously published by the Prison Journalism Project. Follow on Twitter: @RL_Smoke.