In prison, where shared knowledge, creation and individual agency is relegated to cells, corners, and impromptu assemblage on the yard, the few classrooms that remain behind the walls offer incarcerated people a desperately needed space to collectively reflect and intellectually engage with peers. Celes Tisdale’s When the Smoke Cleared: Attica Prison Poems and Journal (Duke University Press, 2022)—a reprint of Betcha Ain’t: Poems from Attica (Broadside Press, 1974)—beautifully documents what it means to bear witness while teaching, and the great responsibility that comes with ushering voices from the inside of prison walls to the outside. More than this, the anthology is a piece of poetic history of what happened in the aftermath of the September 1971 uprising at Attica Prison in New York State.

On May 24, 1972, Celes Tisdale entered Attica to teach the facility’s first ever poetry workshop. Less than a year before, the men housed at Attica staged a five-day uprising, demanding better living conditions and political rights. In his thorough and insightful introduction, poet Mark Nowak contextualizes the uprising at Attica to one that occurred at Dannemora prison in northern New York in July 1929 and to others across the country that happened shortly before Attica. As Nowak shares, the demands at Attica were not unlike those demanded at Dannemora decades before. The men of Attica demanded New York State minimum wage for their mandatory prison labor, religious freedom, uncensored access to reading materials, and a transformed prison education system and library. The upheaval claimed the lives of thirty-three incarcerated men and ten prison staff—the highest number of fatalities in the history of prison uprisings. As Nowak recounts, “They did not put their lives on the line in September 1971 for minor tweaks to the prison system.” The sociocultural importance of their efforts cannot be overstated, as they even inspired volunteers to establish what is now known as PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing program that is publishing this very review.

The urgency and power of speaking the truth forever changed the men Tisdale worked with for over three years. A poet himself, Tisdale understood the importance of putting memory and feelings to the page, and listened closely when his students expressed interest in sharing their work with the public. Collecting their writing into a manuscript, Tisdale approached acclaimed poet Dudley Randall, who agreed to publish the book. That original anthology, Betcha Ain’t: Poems from Attica, was published in 1974 by Broadside Press, the nation’s first publishing house dedicated to publishing the works of Black writers.

Long out of print, the volume has been reissued by Duke University Press as When the Smoke Cleared: Attica Prison Poems and Journal (2022). Poet Mark Nowak, founder of the Worker Writers School, noted the importance of Tisdale’s work in Attica and approached him with the idea to have the book reissued. In addition to a critical introduction by Nowak, the anthology features a new preface by Tisdale and additional unpublished poems from Tisdale’s Attica poetry workshop. The reissued edition has been expanded from the original and consists of three parts. The first two, “Betcha Ain’t” (the original 52 contributing poems) and a journal Tisdale kept while teaching, make up the original 1974 edition. The third section, “When the Smoke Cleared: More Poems from Attica,” features 20 previously unpublished poems from that same initial class of writers. There is also an appendix with teaching material and methods specifically developed by Tisdale.

When the Smoke Cleared is an undeniable piece of history, something Tisdale knew even before the publication of the 1974 volume. From beginning to end, the book is a journey into the world of people who have been cast from society, but refuse to let their humanity fade. Remembering the core of one’s human nature is the thread weaving the tapestry of these poems together. In Tisdale’s epilogue, aptly titled “Remember This,” he employs a collective “we” in speaking as the men who led the resistance efforts at Attica. He says: “We will say, remember this, and never forget / The You of You, like men…” Editing the volume nearly fifty years after its first appearance, Tisdale charges readers with the same invocation he did in 1974. Writing in 2022, he ends the new preface with a clear directive to the reader to use their own memory in the act of witnessing: “Thank you for reading the hearts of these men, and remember just that: they are men of courage who brought the world into their sphere. Remember this.”

Tisdale’s introductory remarks echo over into the book’s first poem, “Forget?,” authored by Brother Amar. The poem itself is a succinct four lines:

They tell us to forget Golgotha we tread

scourged with hate because we dared

to tell the truth of hell

and how inhuman it is within.

Brother Amar uses Christian themes to expound on themes of cultural memory and injustice. In the first two lines, the speaker first declares that they are told to forget their sacrifices, likened here to Golgotha, or Calvary, the site near Jerusalem where Jesus was crucified. Conversely, in the latter half of the poem the speaker identifies that a sacrifice–their crucifixion–was intentionally made by taking a necessary chance of publicly declaring that they were treated unjustly. In four short lines, the poet summarizes the plight of Attica activists who braved consequences in an effort to garner better treatment by prison officials. With these Christian references, Brother Amar situates the anthology as a bible of sorts, a guide into the principles of what it means to live with purpose and in unwavering truth. He insists that what happened at Attica should be remembered—studied even—for generations to come. The title alone works as a continuation of Tisdale’s preface, invoking a call and response between editor and writer, teacher and student. With this, Brother Amar answers Tisdale’s call to remember by responding that forgetting the uprisings and the conditions that led to it should not be an option for anyone.

Critical to the reading of the poets’ work is a keen understanding of the circumstances in which they create. The notes that make up Tisdale’s dated journal are honest renderings of witnessing his students in all of their complexity, in and out of the classroom. He discusses entering the prison for the first time, making house visits to his students’ families, and the conversations he facilitated with workshop participants. Tisdale shares his own perspective, and also steps into the shoes of everyday life for his poetry students that interrupt their shared study.

In addition to reviewing poems the students themselves wrote, Tisdale introduces them to the writing of Shakespeare, Nikki Giovanni, Don L. Lee (now Haki Madhubuti), Waring Cuney, and Amiri Baraka among a long list of others. They discuss different poetic forms such as haiku, and venture into studying drama. Reading the journal alongside the poems, readers can chart the power of Tisdale’s approach to teaching. Most notably, Tisdale documents his students’ many reactions to Nikki Giovanni’s poetry, how they “really ‘come down’ hard on her” for “seemingly having to explain her actions if they seem contrary to the norm.” Later, Tisdale says the group looks at Giovanni and Booker T. Washington objectively because “both figures did what was best for them at a point in history.”

This particular assessment of Giovanni is indicative of how Tisdale’s students experienced Black poetry as intrinsically tied to Black liberation. Their opinions and writings detail the racial climate of the 1970s, attending to the bold, confrontational aesthetics of the Black Arts Movement in the shadow of the nonviolent Civil Rights Movement. When activist and former Black Panther Angela Davis is acquitted of conspiracy to commit murder in 1972, Tisdale reads Giovanni’s “Poem for Angela Yvonne Davis” to the workshop. While Giovanni generally maintained a mixed reception among the men, the influence of her work and Tisdale’s teaching is evident in a poem penned by Harvey A. Marcelin, “Solidarity and/or the More with the United Merrier.” The poems riffs on Giovanni’s poetry in the 1960s and 1970s, and specifically names Giovanni, Davis, and former Black Panther Kathleen Cleaver:

I will not kill a hick

Nor a solitary pig

Or even a Ku Klux honky

But with you

With you

Sisters, let’s

Ice them all.

By addressing these activists by name, Marcelin spells out how artistic, grassroots, and coalition movement building energies outside of the prison fueled the fire within the pens of his peers, and their history-making activism during those five days in September 1971. His poem in particular illustrates that Tisdale’s role as instructor and editor also included serving as a facilitator of conversations between the outside and the inside, demonstrating for his students how they could intellectually engage with other poets and thinkers on the outside.

When the Smoke Cleared is a time capsule of the sharp minds, open hearts, and courageous souls of men brutalized by the United States criminal justice system. In it, the reader will also discover a cruel mirror, reflecting how little America’s relationship to incarceration has progressed. Since the early 1970s, systemic mass incarceration has skyrocketed, making the text as relevant today as it was in 1974. As a result of what happened at Attica, people who are incarcerated are more empowered to vocalize the mistreatment and exploitation they face in carceral institutions in the United States. Nearly fifty years after those uprisings in upstate New York, people held in Alabama’s prison system today are advocating for their rights by staging a hunger strike. The reissue of When the Smoke Cleared is right on time then, for it showcases the full range of complex humanity that incarcerated people carry, in spite of the criminal justice system’s intent on portraying them as unproductive members of society. In this way, the events in Alabama are not isolated events, but they exist within a deep history of carceral resistance. Through Tisdale’s charge for readers to remember the events and people of Attica, we see that we on the outside are meant to not only recognize the continuum of injustice in our carceral system, but can be active players in our own way to support a community of people who are made to feel second-class and inferior.

Malcolm Tariq speaks with Tisdale about his approach to teaching poetry, the process of editing the volume, and the importance of remembering the 1971 uprising through poems.

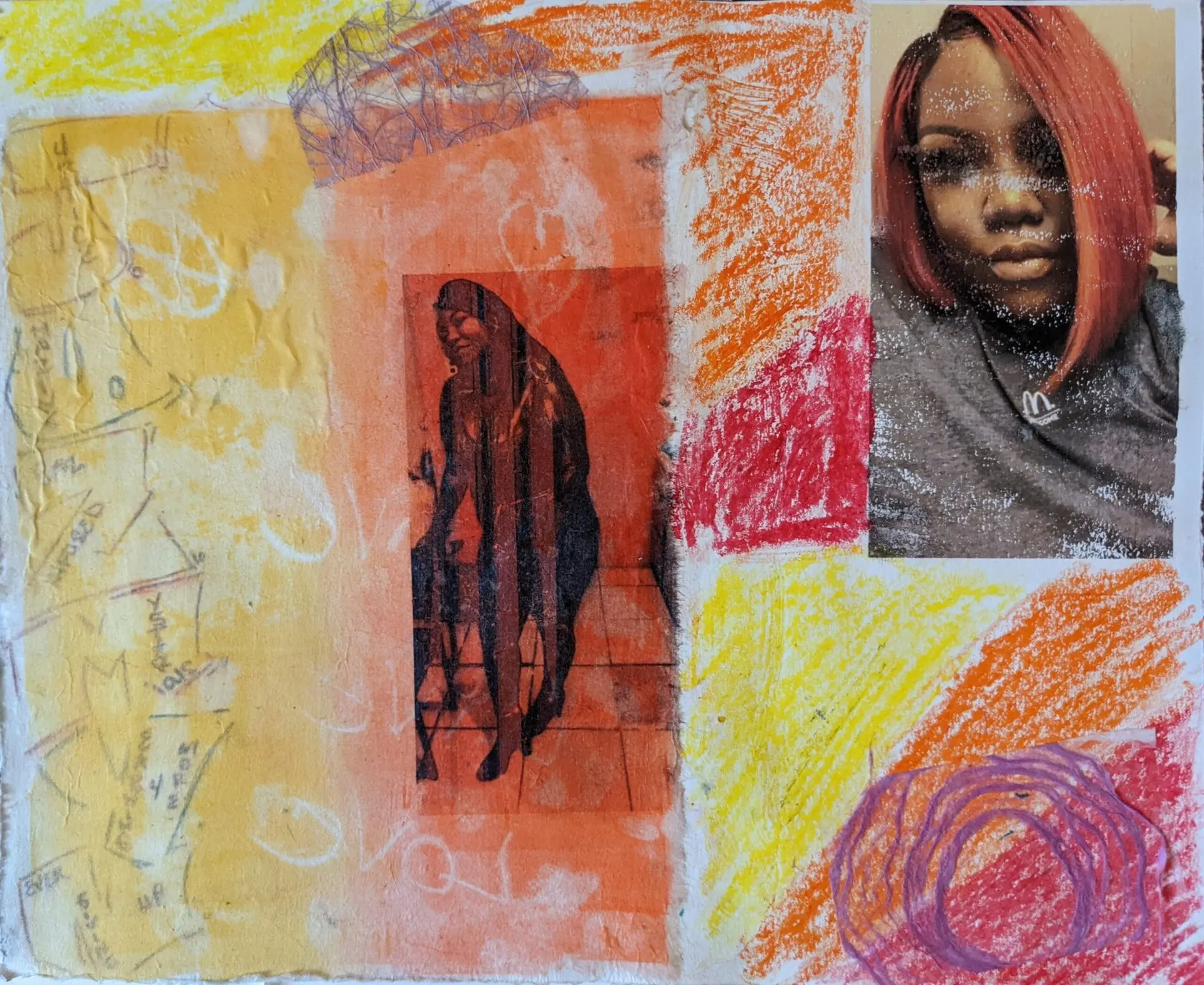

Malcolm Tariq is the senior manager of editorial projects for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing program. His collection, Heed the Hollow (Graywolf Press, 2019), is the recipient of the Cave Canem Poetry Prize and the Georgia Author of the Year Award in Poetry. Originally from Savannah, Georgia, Tariq lives and writes in Brooklyn, New York.