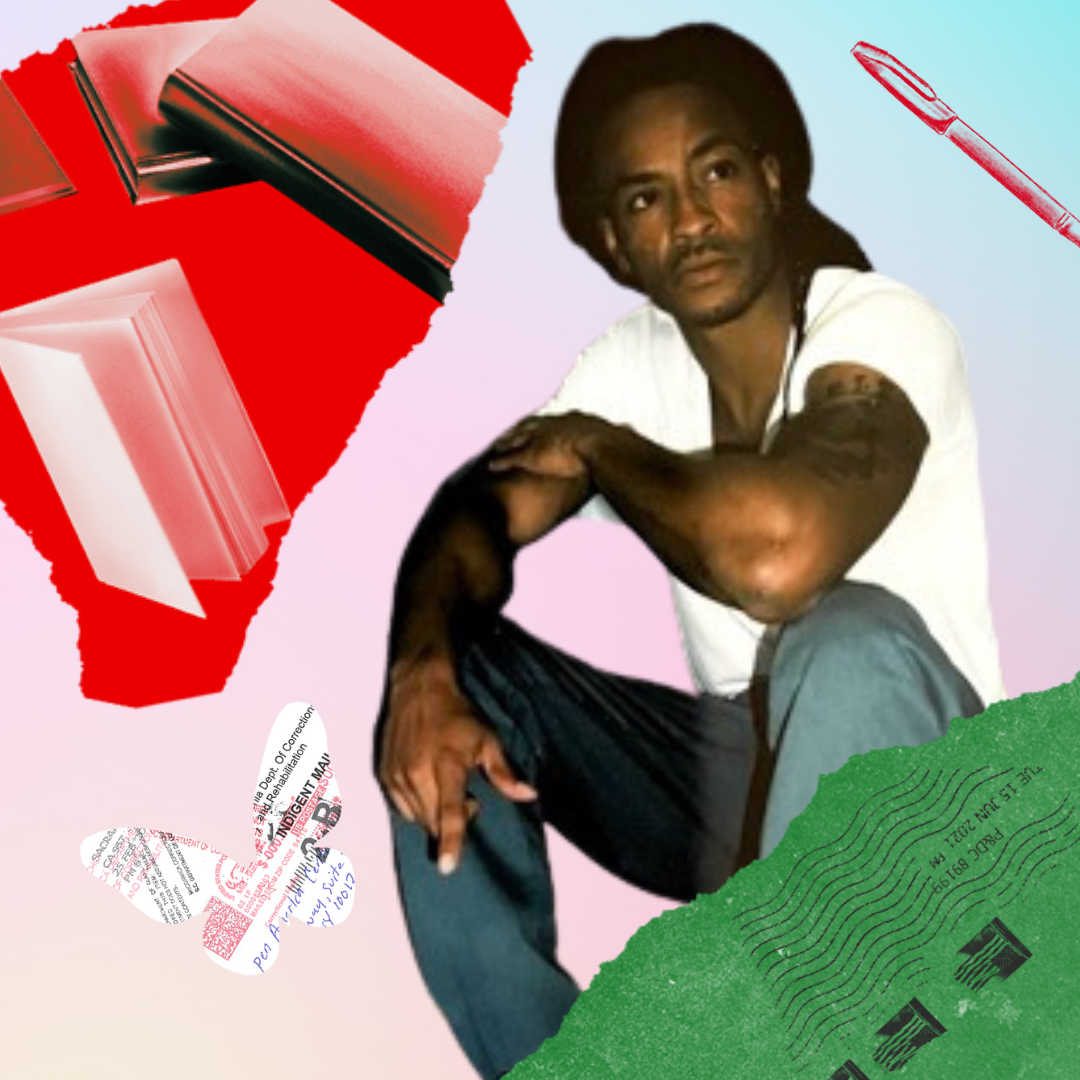

As censorship practices continue to worsen in carceral facilities across the country, receiving books has been an increasingly difficult challenge for incarcerated individuals. Prisons, jails, and detention centers implement guidelines that not only determine which books are permitted inside based on content, but also how those books enter. In practice, the policies for mailing books to people in prison are capricious and inconsistent. That is why Leo Carmona, a writer currently incarcerated in Michigan, was not too surprised when his facility rejected a copy of the PEN Prison Writing Awards anthology that I had sent to him.

When Leo wrote to me on JPay––a virtual messaging system designed for communicating through the walls––letting me know that he was not able to receive the anthology, I offered to send him printed copies of excerpts through regular paper mail. Although engaging with the essays in this way is not comparable to holding the actual book, I thought Leo could at least read them. I also wanted to include articles featured in past issues of our Works of Justice newsletter, as many of them discuss censorship just like he had experienced. Leo graciously agreed, and specifically asked for selections from the “Memoir” section of the anthology, expressing that he has “always felt an incredible sense of camaraderie when reading other prisoners’ writings,” as well as “a sense of kinship with those who may have similar backgrounds and personal struggles.”

When Leo reached out a few weeks later, I expected a short note letting me know the mail was delivered, but I was completely surprised––and deeply moved––by Leo’s message. He sent me insightful, vulnerable, and compelling responses to several of the pieces I had mailed to him. In conversation with Geneva Phillip’s submission, “The Hard Part,” for instance, Leo writes of his own experience with the traumatic forced removal and separation that prison inflicts on those confined within them. Upon reading an interview about carceral censorship practices, Leo reconnects with an old friend, and discusses the importance of using writing as a tool to speak out against injustice, despite the possibility of facing detrimental consequences for doing so.

Leo’s responses are a true testament to the healing and restorative power inherent in the written word. They demonstrate the ways in which writing itself has the ability to cultivate a sense of community and solidarity amongst writers and readers, deepening their connection in spite of the prison walls.

Jess Abolafia

Program Assistant, Prison and Justice Writing

From: LEO CARMONA

Date: 7/7/2023 10:48:22 PM

To: PEN America

Hi Jess,

Thank You for forwarding me a copy of ‘Variations On An Undisclosed Location.’ It arrived today, which was sort of perfect, since it is my birthday. However, my facility DID issue a rejection notice, and I was not allowed to actually receive the book.

Michigan’s DOC policy states that any books sent to prisoners MUST come from one of the following sources:

Directly from Amazon (as opposed to ‘sold’ by Amazon, but ‘shipped’ from a 3rd party)

From Barnes & Noble

OR directly from the publisher.

I sincerely appreciate and am grateful for your having spent the time and financial resources to try to get the book to me. My mother will be visiting me in exactly one week. When she does, she’ll pick up the book and hold it in my personal home collection. It’s just unfortunate for me, that it will be at least six years before I might have the opportunity to read and enjoy it.

Not receiving the book was very disappointing, although not totally unexpected. I’ve now been in confinement for the whole of my adult life, so I’m all too familiar with the arbitrariness of some policies and protocols.

In accordance with DOC Policy, I did avail myself of the option/right to have an administrative hearing on the rejection. However, I did get the impression that the decision to uphold the rejection was made, before I was even summoned for the hearing. The person conducting the hearing, was professional and pleasant enough to interact with, but the hearing was seemingly perfunctory and informal. She all but said that the decision was made at the top administrative level, and there was nothing that she could do, even if she were inclined to. So the actual purpose of the hearing was essentially just for me to decide whether to send the book home, or to allow prison staff to destroy it. (As opposed to meaningfully allowing me to advocate for why it should not be rejected at all).

From: LEO CARMONA

Date: 8/31/2023 11:32:15 PM

To: PEN America

Dear Jess,

I finally just received your mailings by post, and I was astounded, to say the very least. I am nearly at a loss for words. But I’ll try to gather my thoughts.

Geneva Phillips’ piece hit me to my very core. I found it profound on a level that there aren’t enough words to adequately describe. But here is my feeble attempt. It resonated so much, because I have lived and continue to live every word of what she wrote. It is SO hard to leave friends behind, and also to be the one BEING left behind. And after 19 and a half years of incarceration, and SEVEN different facility reassignments, I can say that it never gets easier.

My last move 9 months ago has affected me the worst. After spending 6 years and one month at the Lakeland facility, my custody level was decreased, and I was moved to my present location. Even though I’ve served essentially 2 decades, my previous facility is where I’ve had the absolute BEST community of friends EVER, and the most emotionally rewarding job that I’ve ever had.

The friends I had there, became my family. They were my first group of openly LGBTQ+ friends, and consequently the first group of people I’ve EVER felt “at home” with. We were together, and emotionally clung onto each other throughout the horrors and anxieties of Covid-19. Leo Cardez’s submission also reminded me about how we always cooked elaborate meals for each others’ birthdays. And this year was the first in several years that I didn’t have that in my life.. When I left them to come here last November, I literally cried myself to sleep for almost a month.

In continuing to process and reflect on what Geneva wrote, I thought of something that my close friend, Tyler, once remarked; he said that when I was moved to a different facility, he felt as though someone ripped off one of his arms, and then ran away with it. I found that to be profoundly touching.

This summer, I was able to reunite with one of my best friends––this one, from the earlier days of my confinement. Adam and I had not seen each other in twelve years due to our transfers. It was amazing to be able to catch up, and see how we’ve grown and matured since we parted ways back when we were still in our twenties (and were still trying to figure out how to survive in prison).

But just two nights ago, Adam stopped me as I was leaving my work assignment, and told me that he was, once again, being shipped off to another facility. This time, I do not have twelve more years to wait on reuniting again. I have approximately five and a half years remaining on my sentence, and he has approximately TWENTY years remaining on his. It is difficult to acknowledge, but a very realistic possibility that Adam and I may never see each other again. Whenever I make parole, I will have to wait two years before I can write to him or accept his phone calls according to DOC policy.

While we confront the harsh possibility of being permanently separated, I told Adam that we will in fact see each other again, when we are old men sitting in rocking chairs, taking out our teeth and throwing them at each other. Trying to remain lighthearted and humorous is one of my coping strategies when I’m sad, hurting, or disappointed. Still, the potential of Adam and I never crossing paths again makes me understand Geneva’s writing and Tyler’s analogy even more deeply.

Next up, you’ll never imagine my stunned surprise to see the work of Daniel Pirkel… because I KNOW HIM! He and I were once coworkers for a few years, upstate, at the Kinross facility, where we were both clerks in that facility’s library. We parted ways in ’15 or ’16 when he left to attend his college program. Most coincidentally, I will be applying for that same program, in just ten hours, as I have an appointment at 9 a.m. on Friday to apply for admission!

Dan speaks so much truth. Absolutely zero embellishments or exaggeration. I’m happy that he had the courage to speak out on it through his writing. Many of us are terrified to “make waves” and put ourselves at risk of meeting unfortunate and unjust consequences for what he did. My hats off to him.

It’s getting late, and Jpay will shut off soon, so I’d better wrap this up. Thank You so much for everything.

Leo Carmona

From: LEO CARMONA

Date: 9/1/2023 9:24:00 AM

To: PEN America

Hi Jess,

I wrote last night, to let you know that I received the mailings that you sent. But I was really in a hurry when I wrote, because the Jpay system shuts down at 11:45, and I think it was just after 11:30 when I wrote to you.

I went to bed shortly thereafter, and I couldn’t stop thinking of what Geneva and Dan shared, respectively. I became emotional, because I identified so very strongly with their statements and sentiments. Allow me to set a scene, so to speak:

The housing unit I live in is referred to as a “pole barn.” It has a wide-open architectural footprint. I am one of 160 individuals, who all live in the same big room, although the room is only partially sectioned off, very much like office cubicles in a call center. The big room is divided into 10 such cubicles, with “half-walls.” Each cubicle contains 4 sets of bunk beds, therefore 8 people live in the space that is MAYBE equal in space to 2 parking spaces. There are no doors or full walls on the cubicles. Consequently, there is absolutely no measure of privacy whatsoever. It almost reminds me of animal kennels, just without the chain-link caging. Oh, and the overhead lights NEVER shut off.

I settled in to fall asleep that night, but kept thinking about what I had read. I had to completely cover my head and face with my blankets, as I literally wept. Tears streamed down my face, and I struggled to remain completely silent. In prison, it is extremely taboo and “frowned upon” for males to display any kind of vulnerability or emotion that isn’t anger. Showing vulnerability is tantamount to sending up a beacon, inviting all manner of abuse and victimization.

But I cried. Not only for myself, but for anyone else who lives with the same or similar pain and frustration that I do, and that Geneva and Dan speak of. Prison is supposed to be a time of introspection, repentance, transformation, “correction,” and last but certainly not least, HEALING. This isn’t always the case though. An individual has to WANT to achieve these things, and be willing to “go against the grain” in order to accomplish these goals.

I’ve now been confined for 19 years and 3 months, with 5 years and 9 months remaining on the minimum portion of my sentence. I’ve done a lot of work on myself in these years, and I’ve accomplished a lot. But I’ve done so not because of prison, but in spite of it. In my state, they don’t allow us to take official and meaningful rehabilitative programming until the very end of our sentences. Although, there are SOME voluntary classes that select people are permitted to take.

Not allowing people to take intensive programming until the final year or two of a sentence, I would argue, is counterproductive. It provides way too many years in which we are essentially left to our own devices. Those who actively choose to seek out voluntary rehabilitative classes, and learn meaningful coping skills, are in the minority here. Sadly, those in the majority utilize their time becoming worse and even more broken than when they entered the system. Despite being in a “secure” institution, they continue to feed and service their various addictions. Oftentimes having to victimize others, through thievery and strong-arm robberies, and even monthly extortion schemes, in order to continue servicing these addictions. It’s a perpetual toxic cycle.

Much like Geneva pointed out, we form friendships and bonds as we all go through the struggle of what it is to live in captivity. I have found that our bonds with others are solidified and strengthened when we face the same struggles together. Geneva speaks to the trauma of having friends ripped from you, or for us to be ripped away from them.

Many individual prisons make up the network of any states’ Department of Corrections. For various reasons, it’s quite common for individual prison facilities to “swap” prisoners from these prisons to those ones. There are a variety of reasons why this is done. But each individual prison essentially is its very own community, and even its own “world.” And when someone leaves one “world” to go to the next, it very much feels like that person has died. This is because they are no longer in our “world.” People who leave are often “remembered” and spoken of for sometimes years, much like we’d remember and speak of friends and family who have ACTUALLY died.

Additionally, as Geneva points out, communication between us and those who have left, is discouraged and even outright prohibited. This lends even more to the feelings of “death” of our friends, who are oftentimes integral parts of our very support systems. Sometimes I feel so devastated by the separation of close friends, that I also feel as though I’d rather serve additional time in prison, with these people IN my everyday life, than less time without them in it. I realize that this may sound a bit insane. But this is what incarceration and institutionalization does to the human mind.

I understand how some people in the public would feel and say that prisoners are undeserving of anything but harsh punishment and the most restrictive conditions. But to oppress people more harshly, ends up being more harmful to the public as well. It very much interferes with and thwarts rehabilitation and correction. And because most prisoners WILL eventually be released, I’d say that the average taxpayer has a vested interest in the correction, rehabilitation, and HEALING of people sentenced to prison. We should be encouraged and supported. Some of us have never had that, which is why many of us were broken to begin with.

Leo Carmona

Leo Paul Carmona grew up in Northern California, and is presently confined in Michigan. He is forty-one years old, and has been a guest of the carceral system since the youthful age of twenty-one. His hobbies include: reading, writing, studying, listening to music, crocheting, mentoring new and/or youthful prisoners, and daydreaming about his future. He is passionate about volunteer work, and advocacy. He hopes to one day find employment with one of the organizations that advocate for prisoners and prison reform. He has approximately five and a half years remaining until becoming eligible for parole. (Unless current efforts to revive Good Time in Michigan prove successful.)

He has contributed writings to Pen America, Michigan Justice Advocacy, Safe & Just Michigan, Michigan Collaboration To End Mass Incarceration, (MI-CEMI) The University of Southern California’s Prison Education Project-2022 National Systems-Impacted Writer Contest, and was one of thirteen prisoners to contribute to an article called ‘Voices From A Prison Pandemic: Lives Lost From Covid-19 at Lakeland Correctional’, published by the Ohio State Journal Of Criminal Law, in 2021. In April 2023, The Traverse City Record Eagle published an article about Leo, called “Pushing Hope”, by Mardi Link. (www.record-eagle.com)

Jess Abolafia is the Prison and Justice Writing Program Assistant at PEN America. She graduated summa cum laude with a BA in English and African-American Studies from The College of New Jersey, where she also received an MA in English. Abolafia has instructed a writing-workshop at the only women’s maximum-security prison in New Jersey, empowering incarcerated women to use writing as a tool of healing and liberation. She is also working on several book projects with system-impacted individuals, including co-editing the memoir of an incarcerated woman sentenced to life in prison as a teenager, and compiling the paintings, drawings, and poems of an artist who found freedom through his artwork during nearly four decades of incarceration, including eight years on Death Row.