Against Retribution: An Interview with Daniel Pirkel

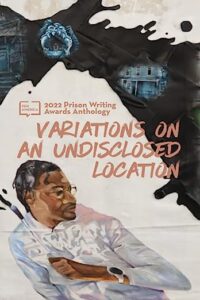

Daniel Pirkel’s essay, “The Unintended Consequences of Retributive Justice,” received a nonfiction honorable mention citation in the 2022 PEN Prison Writing Awards. The essay was published in Variations on an Undisclosed Location: 2022 Prison Writing Awards Anthology, which Pirkel was denied a copy of by the Parnall Correctional Facility in Michigan where he is incarcerated. In this interview, Pirkel speaks with PEN America about his essay, which focuses on the harmful effects of carceral practices that center punishment and how they limit connections between incarcerated people and their families. He highlights unnecessary policies that censor the work of incarcerated writers, and advocates for restorative justice models that would better serve communities.

You’ve been denied a copy of the anthology your essay is published in by your facility. The stated rationale was that, as the author of the essay, you would be able “to exert pressure to have the story distributed by or to other prisoners as a means of communication with or influence of other prisoners confined in [Michigan Department of Corrections] facilities and impact the atmosphere and threaten the order of [the] facility.” Can you talk a bit about this reasoning for people who are unfamiliar with carceral logic?

You’ve been denied a copy of the anthology your essay is published in by your facility. The stated rationale was that, as the author of the essay, you would be able “to exert pressure to have the story distributed by or to other prisoners as a means of communication with or influence of other prisoners confined in [Michigan Department of Corrections] facilities and impact the atmosphere and threaten the order of [the] facility.” Can you talk a bit about this reasoning for people who are unfamiliar with carceral logic?

The reasoning that I could “impact the atmosphere of the facility” is not found in their policy (PD 05.03.118), so it was either contrived by the mailroom officer or someone else. Their concern seems similar to California’s Department Of Corrections and Rehabilitation in Jordan v. Pugh (504 F. Supp 2d 1109, 1121 [2007]), when they said that they were concerned that a prisoner with a published book could attain a “big wheel” (i.e. celebrity) status. This supposedly allowed such prisoners to manipulate others, and made staff feel uncomfortable doing their jobs and exercising their right to free speech. Prison officials also claim that they need to prohibit prisoners from publishing books because it’s ‘akin to running a business.’ The court struck down the staff’s reasoning, with a judgment in favor of the incarcerated writer. Still, prison staff often disregard such laws because the courts do not hold prison staff personally accountable, even when they willfully violate the law.

I believe prison officials’ true reason for this denial stems from the topic of my essay. They want to reduce the amount of criticism they receive. Many imprisoned writers discuss the conditions of confinement, and this can encourage people outside as well as inside to more critically examine the carceral system in this country, which is the largest the world has ever seen. While courts have said that officials cannot censor material simply because it’s critical of carceral systems, individual actors, or institutions, rejections like this often are simply not challenged. They count on people not knowing and not caring whether information is repressed. This ultimately has the effect of discouraging incarcerated authors from writing.

“I believe prison officials’ true reason for this denial stems from the topic of my essay. They want to reduce the amount of criticism they receive. Many imprisoned writers discuss the conditions of confinement, and this can encourage people outside as well as inside to more critically examine the carceral system in this country, which is the largest the world has ever seen.”

Your essay focuses on the erroneous calculations of retributive justice. What is retributive justice and what’s an alternative?

Retributive justice involves the idea that the primary goals of criminal justice revolve around retribution (revenge), deterrence (deterring), and incapacitation (disabling). Embracing retributive policies justifies punishing offenders in order to satisfy society’s desire for vengeance, which may also deter them and other potential offenders from engaging in future crimes. While these three goals can more or less work together, they run contrary to rehabilitation, as seeking to punish prisoners (beyond the necessary hardships of prison) encourages people to adopt antisocial attitudes and behaviors.

People are justifiably sick of hearing about abhorrent criminal behavior on the news. They just want someone to do something! Since the only thing that seems to scratch this itch involves attaining retribution, the public cries out for tougher sanctions (regardless of how harsh the current ones are). However, statistics show that tough-on-crime policies (e.g. war on drugs) don’t reduce crime. While incapacitation may logically help, scholars Norval Morris and David J. Rothman state that “research into the use of imprisonment over time and in different countries has failed to demonstrate any positive correlation between increasing the rate of imprisonment and reducing the rate of crime” (xii). Even when corporal and capital punishments were the norm, many Americans were not satisfied with the criminal justice system.

The only alternative to retributive justice involves helping to rehabilitate prisoners. Despite academic research that demonstrates rehabilitation is possible, the current system is antithetical to it. Instead, most prison staff only “engage” in rehabilitative efforts whenever it’s convenient, such as to justify expenditures or to protect their jobs. Prisons function to mete out punishment, which essentially makes incarceration a form of torture. Conservatives sometimes indicate that punishment is necessary to “balance the scales of justice” in a vague, metaphysical way. However, what punishment actually yields is more victims. The majority of incarcerated people were first victims, and even those who were not became victims once incarcerated. The daily fight for life inside is dehumanizing. Prison guards and officials often allow acts of violence and cruelty between inmates. They enforce petty rules while allowing or even encouraging conduct that contributes to antisocial behavior.

There are various alternatives to retributive justice, such as restorative justice. This would create a system that focuses on restoring the person who was victimized, the negative impacts a community experienced, and addressing the needs of the person who committed the harm-doing. It also offers the chance to reestablish or establish relationships between people involved, as much as possible. Essentially, it seeks to address the harm instead of prioritizing punishment at the exclusion of everything else. While not the only alternative, the broad concept of restorative justice encourages us to see all people involved as part of our community and part of the solution to violence and harm-doing. Everyone needs hope and encouragement, as well as corrective guidance, to change. While we cannot create a perfect system, focusing on rehabilitation is the best way to heal. As Morris and Rothman said in The Oxford History of Prison, “it’s hard to train for freedom in a cage” (x).

Were you concerned about potential negative ramifications from publishing this piece?

My essay points out how unnecessary policies stifle relationships. In my case, the Michigan Department of Corrections sent me to the Upper Peninsula to serve my sentence, which required me to wait three years before being placed on a waiting list to be transferred down state. Due to mental illness, my brother could not make the 8.5-hour drive to visit me upstate. I wrote this piece because I wanted to highlight the extreme consequences that result when administrators support unnecessarily harsh policies and rules, as well as the consequences of having a system that sees itself as punitive above all else. In the past, criminal sanctions used involved corporal punishment. Today, they use a more benign form: negligence, limited movement, restricting activities, and controlling incoming/outgoing communication. Some Americans consider such a punishment too soft. This perspective doesn’t understand the consequences for society in general, though. For those directly impacted, it’s like death by a 1,000,000 cuts, but it also manufactures more harm that is dispersed again once people are released. The recidivism rate demonstrates how the carceral system in the United States actually creates much of the violence it claims to be containing.

I never considered that the MDOC would take the position of denying me access to my published work, but I am well aware of their ability to retaliate against me for my writings. Most prisoners never file grievances because of the knowledge that the government literally has our lives in the palms of their hands. It’s not too difficult to imagine a staff member writing a secret report or otherwise contacting the parole board. Prisoners are unlikely to ever learn about these reports and actions, as we cannot file Freedom of Information Requests to see what is in our file. Further, prisoners rarely feel confident in filing a grievance because it almost never has any effect on their living conditions, no matter how reasonable the complaint.

“I never considered that the MDOC would take the position of denying me access to my published work, but I am well aware of their ability to retaliate against me for my writings. Most prisoners never file grievances because of the knowledge that the government literally has our lives in the palms of their hands.”

What was your motivation for writing this essay?

I wrote “The Unintended Consequences of Retributive Justice ” because I was devastated by my brother’s death. I still feel like throwing up every time I think about him. I see my incarceration as directly contributing to his death. Thinking about him makes me think about the sins I’ve committed, and how I’ve messed up my life. Although I primarily blame myself for my incarceration, I recognized that the criminal justice system’s treatment of me also contributed to the tragedy. My imprisonment prevented me from helping him with his mental health issues. It denied us a meaningful relationship, and isolated us both. While I was not the only person who could have helped him, I was his closest friend before incarceration killed our connection.

I wrote this piece to wake people up to the problems, as well as offering a solution. I appealed my Circuit Court’s decision when the judge refused to appoint me a new appellate counsel after the first one abandoned my case. This original counsel summarily dismissed my legal issues based on the false premise that people cannot withdraw their pleas based on ineffective assistance of trial counsel. Even so, it took me 12 years of representing myself before I won an appeal in the Sixth Circuit (Pirkel v. Burton, 970 F3d 684, 2020). This is quite a feat, as less than one percent of noncapital habeas corpus petitioners receive any type of relief in the federal courts. Still, I can’t take all of the credit, as they appointed Sundeep Iyer to make an oral argument and verify my claims before the Sixth Circuit.

My journey is not over yet, as the Sixth Circuit’s relief simply required the state courts to appoint new appellate counsel, who also botched my appeal. So I’m making a run at it again after 15 years of incarceration. None of the judges or attorneys were sanctioned for their flagrant violation of the law even after I proved it the first time. Even so, I helped to create precedent that other prisoners can use to fight unjust convictions, and I try to maintain my delusional hope that I can do it again.

Works Cited

Norval Morris and David J. Rothman (editors), The Oxford History of the Prison: The Practice of Punishment in Western Society (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Note: PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program (PJW) finds it important to combat the erasure of the individual when considering language. As such, PJW rejects flattening state language such as inmate, convict, felon, or prisoner used to describe or refer to people who are incarcerated. Nevertheless, we are also committed to preserving the language incarcerated people choose to use in reference to themselves, their communities, and their experience with the carceral system

Daniel Pirkel was born and raised in Indiana and spent much of childhood playing football and video games and riding motorcycles. Since being incarcerated 15 years ago, he has earned a bachelor’s degree in Faith & Community Leadership and Social Work through Calvin University. Pirkel’s essay “The Unintended Consequences of Retributive Justice,” received an honorable mention citation in PEN America’s annual PEN Prison Writing Awards, and is published in Variations on an Undisclosed Location: 2022 Prison Writing Awards Anthology (2022). His essay, “Parole Reform,” received an honorable mention citation, and is published in As I Hear the Rain: 2019 Prison Writing Awards Anthology. His work has also been published with the Prison Journalism Project and the American Prison Writing Archive.