Trouble in Censorville: Teachers Describe Trauma Inflicted in the War on Education

By Julia Goldberg

Panic attacks. Debilitating depression. Social isolation. Insomnia, weight gain, hair loss. These are some of the symptoms that 14 public school teachers describe experiencing in Trouble in Censorville, a collection of oral histories that demonstrates the human cost of the campaign against education undertaken by extremists.

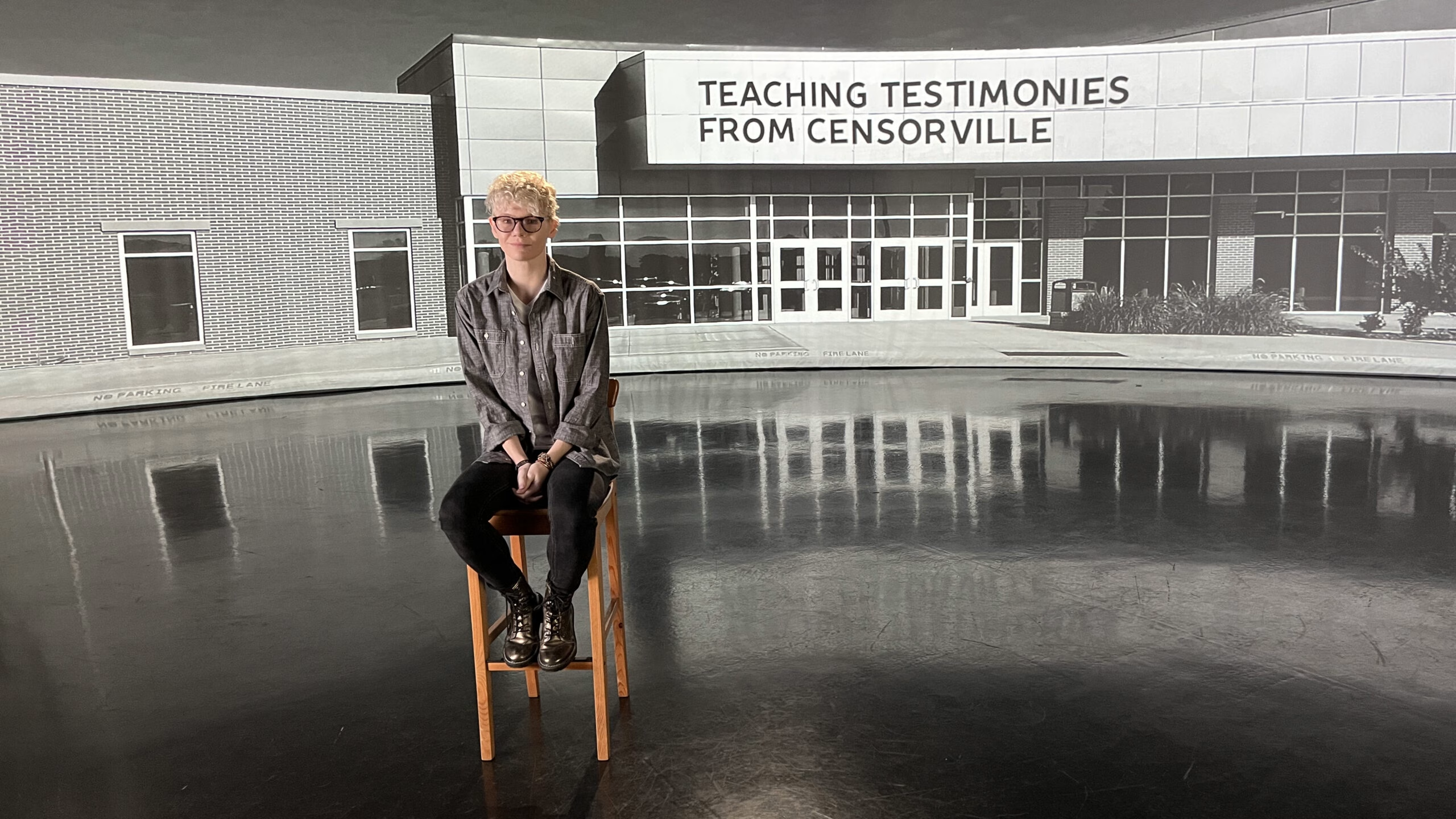

Co-editors Rebekah Modrak and Nadine M. Kalin conducted all of the interviews featured in Trouble in Censorville with educators facing new challenges in the current climate of educational censorship and book bans. To protect the educators they spoke with from retaliation, Modrak and Kalin provided many of them with pseudonyms and all of them with a new place to call home.

“The first few people we interviewed could only speak to us under the condition of anonymity, and we used ‘Censorville’ as a fill-in-the-gap term for a while, and then we started to realize that was the place we were really talking about,” Modrak told PEN America. “We liked the idea of joining all of the teachers experiencing censorship together in one location because it is such a shared experience.”

Along with a litany of detrimental effects on their mental and physical health, the teachers in Trouble in Censorville have been threatened, harassed, and placed on leave or fired for teaching students about aspects of American history and contemporary society including slavery, the genocides of Indigenous peoples, and LGBTQ+ rights.

The book includes testimony from Melissa Grandi Statz, a fourth grade teacher in Wisconsin who taught her students about racism and the Black Lives Matter movement. She was threatened and harassed online, facing accusations that she was “a terrorist” and “mentally abusing children.”

“I tried to distance myself from some of the things they were saying and pretend, ‘This isn’t real.’”

A Facebook group called “Parents Against a Rogue Teacher” began spreading rumors about Statz and developed a plan to have her fired. Multiple parents posted photos of their guns in the group, and others encouraged the rest of the group to find out where she lived and what social media platforms she used. “I tried to distance myself from some of the things they were saying and pretend, ‘This isn’t real.’”

Monica Coles, a nonbinary elementary school teacher who used she/her pronouns while at school, was placed on leave after rumors circulated that students had asked why they looked the way they did — why they had short hair and why they wore pants — and that Coles had responded by ranting to the class about gender and pronouns. “None of that happened. No one ever asked about the way that I dressed. It was just completely false and I told my principal that.”

They were then confronted with art projects they created in college that included nude figure drawings. “Parents were saying that I was drawing minors, and I learned later that they had actually called 911 that Monday morning, saying that their child would be in danger if they were put into my classroom. … HR even was like, ‘Obviously, this is not true. You went to art school to get an art degree and to be an art teacher. This is obviously a wrong situation, but we need to put you on leave because this has created a distraction.’”

“I learned later that they had actually called 911 that Monday morning, saying that their child would be in danger if they were put into my classroom.”

“I was completely shocked,” she said. “I had a full-on panic attack. I was diagnosed with severe anxiety and depression and had to go on medical leave for the remainder of the school year.”

But Trouble in Censorville is not a narrative of defeat: the educators it spotlights have garnered support from colleagues, parents, and students, all of whom are fighting back together. The testimonies they share are characterized by resistance and resilience.

Jonathan Friedman, the director of free expression and education programs at PEN America, contributed the foreword to the book, which provides context about the growth of censorship and the urgent effort to save public education.

“As I write in May 2024, across the United States teachers, librarians, and school administrators are reporting a chilled educational climate in which they are more concerned with running afoul of new censorious laws than with educating their students,” Friedman writes. “This climate is the result of numerous legislative efforts to restrict what is taught in public schools, which have been scaffolding upon one another since 2021.”

In January 2021, the nation’s very first state-level educational gag order was introduced in Mississippi — and between then and December 2023, PEN America tracked the introduction of over 300 educational gag order bills by 45 U.S. state legislatures.

On July 1, the day of the book’s publication, Censorville.com will go live with a number of videos, including recordings of the educators — or actors portraying them — reading their full testimonies, as well as an exclusive interview with Friedman.

“I had a full-on panic attack. I was diagnosed with severe anxiety and depression and had to go on medical leave for the remainder of the school year.”

The origins of the book can be traced back to the pandemic, when Modrak, an artist and professor at Stamps School of Art at the University of Michigan, attended many of her daughter’s high school’s board meetings. The rhetoric employed in those meetings by other parents, many of whom identified as Democrats, began to worry Modrak. “They were projecting a consumer mentality onto public school education,” she told PEN America. “They were saying things like, ‘My tax dollars are going to fund education, and so therefore I’m in a position where I should be making decisions about whether the teachers are back in the classroom before they’re vaccinated.’”

Concerned, Modrak compiled many comments from the meetings and hired a Donald Trump impersonator to read them aloud. She filmed the impersonator and then presented the video during another school board meeting, she said. “It was the first time some of these parents were confronted with the idea that their language might be very Trump-like and actually not the Democratic model of politics.”

Modrak later wrote a chapter on the experience for a book, which she sent to educators she believed would be interested in its contents. Nadine Kalin, an educator at the University of North Texas, wrote back to Modrak about her work, and a creative partnership was born.

The pair began chatting about the state of public education and soon after spoke with Monica Coles, the elementary school teacher and one of Kalin’s former students, who was only four days into their job as a teacher when they were fired for not looking like their coworkers. Modrak and Kalin initially planned to create a video series highlighting the stories of educators like Coles, but they soon realized they had a book project on their hands. They interviewed between 20 and 25 educators in total, many of whom were referrals from previous interviewees, Modrak said.

One of the project’s primary objectives was to provide teachers with complete control over their narratives. “The news media, as much as they might be trying to get things right, are telling fragments of [teachers’] stories as a part of a larger story that often has other agendas,” Modrak explained. “Teachers and librarians wanted to tell the story in their own words rather than through the words of a journalist.”

The media often didn’t highlight how teachers were personally affected by educational censorship — the isolation they faced from their communities, the panic attacks they began experiencing — and it also frequently omitted the rallying cries that followed censorship, she added.

In addition to the 14 testimonies, Trouble in Censorville contains a historical timeline spanning from 1865 to 2024. The timeline provides details about events and trends in education referenced by teachers, allowing readers to understand every step of their narratives.

Modrak and Kalin hope their book reaches other educators throughout the nation, providing them with a sense of solidarity, as well as parents of children in public schools who might not be aware of the current severity of censorship.

Trouble in Censorville is available in e-book and print at Disobedience Press and other booksellers. All of its profits will go toward the educators it features.

Julia Goldberg is a communications intern at PEN America.

Related Content

Teachers and Librarians Describe a Climate of Fear Stoked By New Laws

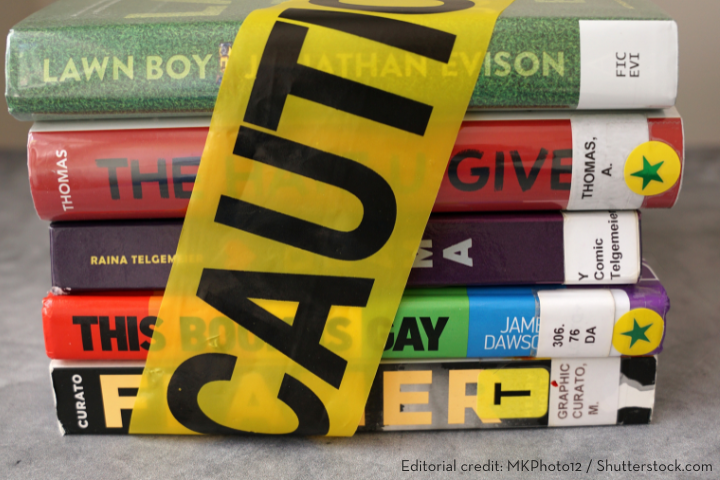

Spineless Shelves: Two Years of Book Banning