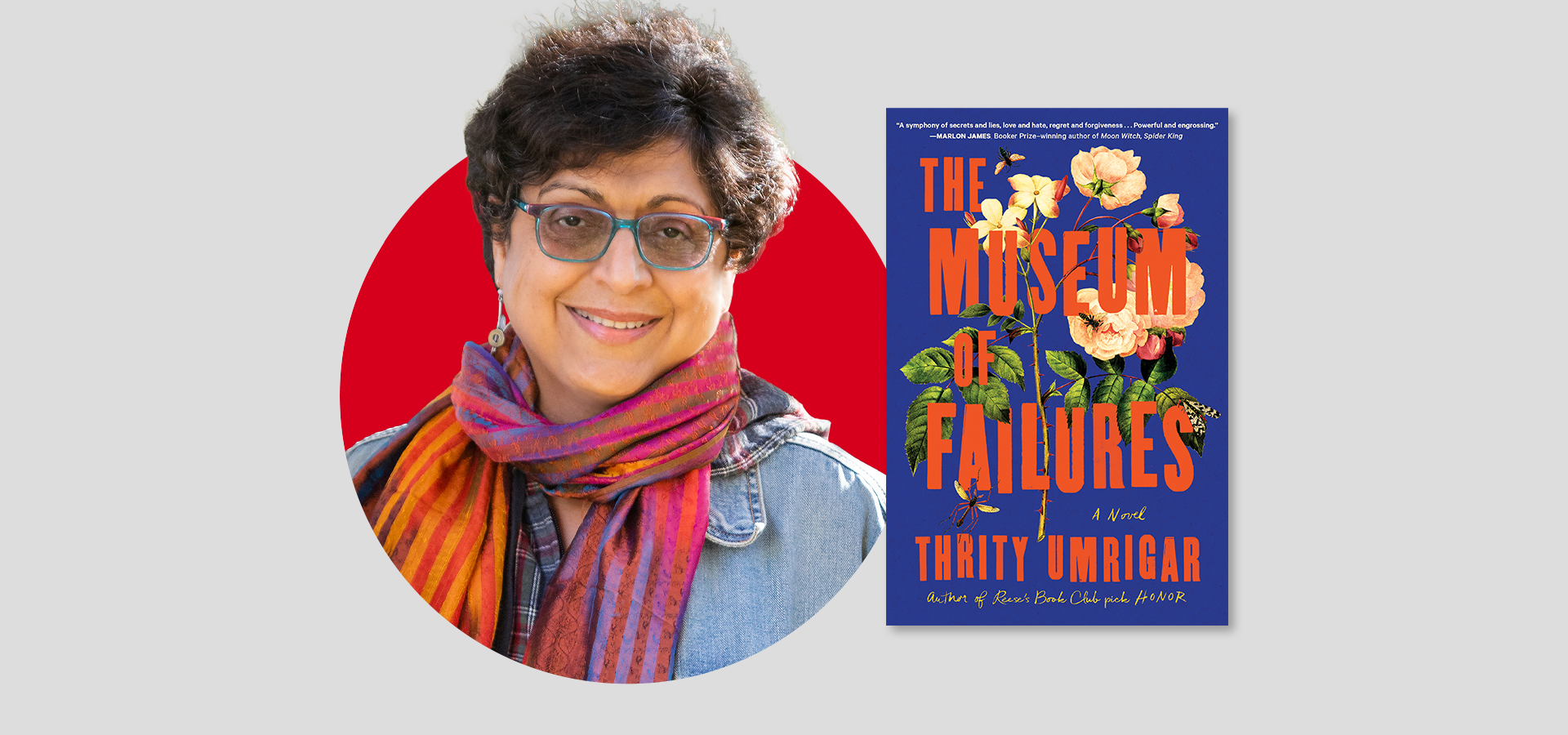

Thrity Umrigar | The PEN Ten Interview

September 28, 2023

Immersive, intimate, and deeply felt, Thrity Umrigar’s The Museum of Failures (Algonquin Books, 2023) explores the power of forgiveness and the eternal possibility of new beginnings. Remy Wadia returns to Bombay from the United States, planning to adopt a baby from a young pregnant girl—and to see his elderly mother again before it is too late. As shocking family secrets surface, Remy finds himself reevaluating his entire childhood just as he is on the cusp of becoming a parent himself. Can Remy learn to forgive others for their human frailties, or is he too wedded to his sorrow and anger over his parents’ long-ago decisions?

In conversation with Literary Awards Program Director Donica Bettanin, for this week’s PEN Ten, Umrigar discusses her long publishing career, the power of language, and moving between worlds, or, “life on the hyphen.” (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

1. The title refers to how Remy views his hometown of Bombay: the “Museum of Failures.” Why was it important to set the story in this city?

Remy is a Parsi, a member of a tiny ethno-religious community that is largely settled in Bombay. The Parsis of India are a Westerned, progressive community and have been integral to the building of modern Bombay. So it made sense to set his story there. Also, I grew up in Bombay and I know the city better than any other city in India. I know how the Parsis in Bombay talk, act and think. Setting the story here allows me a degree of authenticity that I wouldn’t have been confident of, if, say, the novel was set in New Delhi. So it made sense to set the novel here.

2. Remy’s childhood reverberates through the novel. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

Oh, I had a very useful lesson about the power of words. I had my first short story published in a major national magazine when I was about sixteen years old. The story, told in the first person, was narrated by a young, disgruntled young boy whose father is a laborer and an alcoholic. To the narrator his father is an object of scorn and pity; he blames his father for not rising above his station by any means necessary. My story was intended to be a sympathetic portrayal of both father and son. It was the first time I’d ever submitted anything for publication. I still recall my stunned response and elation when I saw my name in print for the first time. I came home triumphantly, waving a copy of the magazine. My family read the story for the first time. What I was unprepared for was my beloved aunt Jeroo’s reaction. She was my dad’s unmarried sister and lived with us. I loved her madly. But she was furious about the story, something that blindsided me. It turned out that she thought that I was the narrative voice and the story was a criticism of my dad, her beloved brother. I was stunned by this ridiculous misunderstanding. The narrator was male, poor, uneducated–the opposite of me. I tried explaining this to her, to no avail. I think this was the first time (and the only time) in her life that she was angry at me. Once I got over the shock, I learned about the power of language, of words, both positive and negative. It was an unforgettable lesson.

“I’ve always been interested in the insider-outsider dynamic. That’s because I’m interested in examinations of power–who has it, who doesn’t, who uses it against whom. And being an immigrant myself, being Indian-American, I’m fascinated by the notion of ‘life on the hyphen.’”

3. The reader learns of “That persistent hope, the immigrant’s dream of braiding the disparate strands of his life together…” Is this a tension that you find yourself returning to as a writer?

Yes. I’ve always been interested in the insider-outsider dynamic. That’s because I’m interested in examinations of power–who has it, who doesn’t, who uses it against whom. And being an immigrant myself, being Indian-American, I’m fascinated by the notion of “life on the hyphen.” In my case, that hyphen has been filled with promise and opportunity and good fortune. But I’m aware of the fact that this is not true for all immigrants. And despite having every privilege, I can still relate to that longing to braid the disparate strands of my life together, that merging of past and present, that feeling of the divided self.

4. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

Too many to name but here’s a valiant attempt. To start with, the British children’s writer Enid Blyton, whose adventure novels were the first books I read and laid the foundation of my reading and writing life. In my teenage years writers like Steinbeck, Hemingway, Fitzgerald became crucial to my development as a writer. In my twenties, I discovered Virginia Woolf and Toni Morrison and James Baldwin. They became my lodestars. Salman Rushdie was very important to my life, but thankfully he’s not a writer from the past because he’s very much with us.

“If I approach my characters with humility and integrity—then I can and will write about fellow human beings who are outwardly different than me. Because what I’m most interested in is examining the systems and forces that create divides between people, those power dynamics that separate us. I want to write about the inner lives of people, not their superficial characteristics. So, I don’t call any of this self-censorship. I call it respect.“

5. This is your tenth novel. How does publishing a book feel different now from when you started out?

When I sent off my first novel, Bombay Time, to an agent I honestly didn’t think I’d find a publisher. I had no self-confidence and I had no community of writers to encourage or discourage me. The only ‘community’ I had were the published writers I was reading and once you read Toni Morrison, you want to hang up your gloves before you start. At that time, I was still a newspaper reporter and that was my world. I had no idea if anyone would be interested in reading about this quirky world of Parsis that I had created.

Today, the stakes seem higher because I’ve had a twenty plus year career as a novelist. But I still feel the same insecurity and uncertainty that I did at the start of my career. It’s a tough business, publishing, and you’re only as good as your last book. I still worry about never getting published again. But one thing has remained constant–that thrill one feels when you hold a copy of your new book in your hands for the first time. It’s a high unlike any other.

6. Have you ever had to navigate censorship—or self-censorship—in your writing?

I wouldn’t go so far as to call it censorship. Indian culture, about which I often write, hasn’t yet gotten the memo about being politically correct. Their everyday language is coarser than ours. They routinely use words like, “stupid,” “idiot,” “cripple” etc., words that offend modern American sensibilities. In order to give authenticity to my characters, I have them speak like this. My American editors often point this out to me and ask for changes. If I don’t think it harms the novel, I will modify it. If I think it’s important to leave in, I’ll stick to my guns. I trust my editor implicitly. We both work in the service of the book. So it’s a partnership I trust.

The question of self-censorship is trickier. I often write about religious groups in India–Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Parsis. I’ve received scathing letters from readers whose religious feathers were ruffled by my depiction of their community. Indians are extremely sensitive to how they are portrayed in the West. It is my job to parse when their criticism is valid and when it is simply a protest against airing one’s dirty linen in public.

In the past several years, there’s also the debate of whether writers of one race can write about another. I have pondered this question for a long time and understand where people on both sides of the issue are coming from. In the end, I’ve decided that if I do my job well–that is, if I research the heck out of my subject matter, if I create fully-realized characters and not caricatures, if I’m respectful of the community I’m writing about, if I approach my characters with humility and integrity–then I can and will write about fellow human beings who are outwardly different than me. Because what I’m most interested in is examining the systems and forces that create divides between people, those power dynamics that separate us. I want to write about the inner lives of people, not their superficial characteristics. So, I don’t call any of this self-censorship. I call it respect.

7. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

I always enjoy reading nonfiction when I’m actually reading it, but I mostly read fiction. I love literary fiction–stories about human beings in their daily lives. I don’t read much genre fiction, although my students at Case Western Reserve University keep trying to turn me on to sci-fi. I haven’t read too many crime thrillers or mysteries, although that’s a genre I’m getting more interested in.

8. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

My book tours have taken me around the country and I have read at fabulous bookstores–the Tattered Cover in Denver, Book Passage in Corte Madera, Books & Books in Miami and McLean and Eakin in Petoskey, MI. But I have to give a shout-out to Loganberry Books, a wonderful, woman-owned bookstore in Cleveland. The large, gorgeous store has about 100,000 titles in stock and it’s like walking through a book wonderland.

“When the reader holds a book, they bring their entire life experience to bear upon that book. In doing so, the book is transformed–instead of dead words on the page, the book now becomes three—dimensional, the words rise off the page and enter the reader’s life.“

9. You also teach writing; is there a teacher or a lesson you recall as essential to your own education as a writer?

I became a writer because of my high school English teacher, Greta Marquis. She was a devoted teacher who not only infected me with her passion for books, but instilled confidence in me about my abilities as a writer. I remember being so intimidated by the thought of studying Shakespeare in seventh or eighth grade. But Ms. Marquis not only made the Bard accessible, but fun. It was a game-changer.

In my Ph.D. program, my poetry teacher Maggie Anderson was a big influence and inspiration. We became lifelong friends. And during my Nieman Fellowship at Harvard, I took a writing class with the late, great Brad Watson. I workshopped the first chapter of my first novel in his class and his enthusiastic encouragement kept me going.

10. Writing is often a private and intimate process. Now, The Museum of Failures will also belong to readers. How do you prepare for that?

I have always believed that as soon as a book hits the shelves, it belongs to the reader. A book is a sort of interpretive dance between reader and writer. When the reader holds a book, they bring their entire life experience to bear upon that book. In doing so, the book is transformed–instead of dead words on the page, the book now becomes three-dimensional, the words rise off the page and enter the reader’s life. It’s a magical transformation that is the lifeblood of literature. A book without readers is just a pile of dead trees.

Thrity Umrigar is the bestselling author of nine previous novels, including Honor, which was a Reese’s Book Club Pick, as well as three picture books and a memoir. Her books have been published in over twenty countries and in several languages. A former journalist, she has contributed to the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, the New York Times, the Cleveland Plain Dealer and other newspapers. She is a recipient of the Nieman Fellowship to Harvard, and winner of the Cleveland Arts Prize, the Seth Rosenberg prize and a Lambda Literary award. She is currently a Distinguished University Professor of English at Case Western Reserve University.

C Pam Zhang | The PEN Ten Interview

Like language, food is essential and theoretically accessible to almost anyone. The real question is which culinary voices are permitted, celebrated, amplified, valued.

Isle McElroy | The PEN Ten Interview

It can feel amazing to be taken care of, to be known, but it can also feel limiting if one is shown things about oneself that are difficult to confront.

Sam Sax | The PEN Ten Interview

I think in that same way that every poem teaches you how to read it, every poem you make teaches you how to make it as you’re writing.

Sola Mahfouz & Malaina Kapoor | The PEN Ten Interview

In Afghanistan, laughter is as much a part of life as sorrow and pain. People crack jokes while hiding from bombs in basements, finding humor in their grim reality.