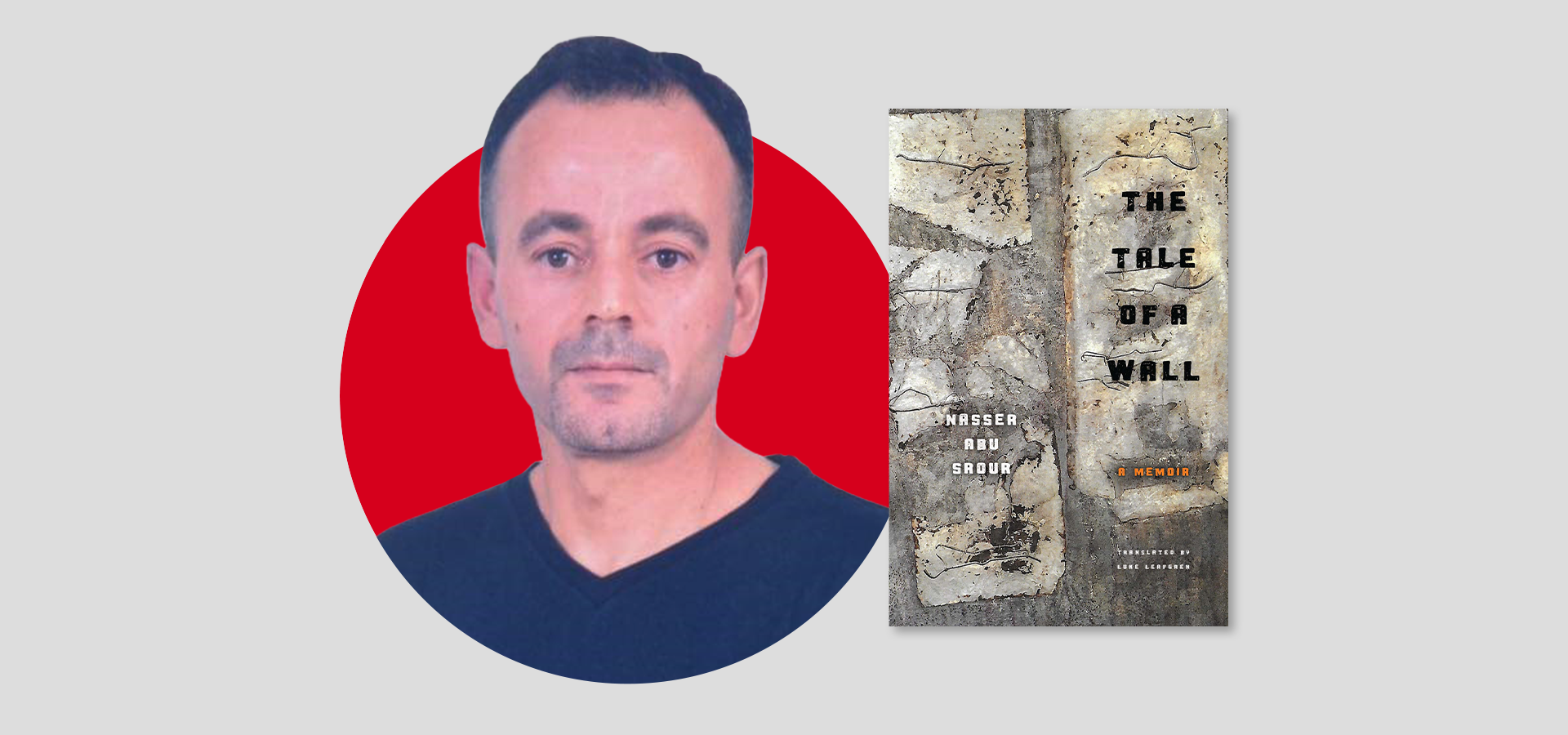

‘The Tale of a Wall’ by Nasser Abu Srour | The PEN Ten Interview

April 30, 2024

Nasser Abu Srour’s passionate, haunting autobiography, The Tale of a Wall: Reflections on the Meaning of Hope and Freedom (Other Press, 2024), provides a historical and personal glimpse into the struggle and resistance of the Palestinian people living under Israeli occupation. Abu Srour, who writes from a cell where he is serving a life sentence with no chance of parole, transcends his pain by writing about poetic justice, revolutionary love, and finding inner stability in chaos.

From his recounting of life in a refugee camp, where his portrait as a freedom fighter now dots the walls, to being sentenced to life in prison, Abu Srour heartbreakingly interweaves the personal and the political, and yet reminds us to find hope and joy in times of struggle and bravely voice our narrative even when being silenced.

In conversation with Prison and Justice Writing Director Sonya Soni, translator Luke Leafgren and publisher Judith Gurewich discuss the importance of amplifying the writing and voices of those under the carceral state, dismantling dominant colonial narratives, and the politics of publishing during a time of human rights violations against Palestine. Due to the circumstances around Nasser Abu Srour’s incarceration, no one was able to communicate with him directly for this interview. (Bookshop)

1. It took Nasser Abu Srour two years and three months to get his manuscript out of prison walls. Could you detail for us the structural challenges and subversive paths you took to release his writing into the world?

Judith Gurewich: We have heard details about the story of how Nasser Abu Srour managed to write his manuscript in prison and deliver it to his publisher in Lebanon, the prestigious Dar Al Adab. But given our concern for Nasser, we would not want to say anything that might put him at risk in any way. We hope he will one day be able to share that remarkable story himself. Other Press became involved after we began looking in early 2022 for a project coming from Palestine. Nasser’s book was recommended, and when a trusted friend read the book in Arabic and described the impact of reading it, Other Press bought world rights and began the next steps of sharing this story as widely as we could. It was the first time that I (Judith) have ever bought the rights to a book that I haven’t read myself. That’s how important I thought this book would be.

2. Amidst global carceral censorship and the systemic erasure of Palestinian cultural identity and artistic voice, both inside and outside prison walls, how do you resist the surveillance and silencing of the writing of authors such as Abu Srour and maintain their authenticity in publishing their brave truth telling?

JG: The bravest person in this story is Nasser, of course, who wrote his story and found a way to get it beyond the prison walls. Our job, as publishers and translators, is to help Palestinian writings reach an audience. When I was at the Frankfurt Book Fair in October 2023, the organizers had just canceled the presentation of an award at that event to Adania Shibli for her novel Minor Detail. I insisted that we continue discussing Palestinian literature and used every opportunity I could to do so. With this specific project, I have not encountered any significant resistance. Indeed, I’ve found great hunger for a book that shares a perspective like this, as seen by all the reviews that are coming out and the publishing houses in England and Europe that will publish it. Of course, that does not change the systematic erasure that is occurring, which is based on untenable arguments. So, it is particularly gratifying for me to publish a book like this. The clarity and insight of Nasser’s writing compels readers to engage and consider what he says, unless they come to the book from a position of bad faith.

3. What do you feel the roles are of literary and publishing communities in this time of unimaginable human rights violations against the Palestinian people?

JG: The best we can do is publish books that reveal those human rights violations. When we find literary voices that bear witness to violations, and even transcend such unconscionable abuse with insights and stories that are gripping for their own sake, we hope to build momentum for change. But literature goes beyond revelation of evil: it restores dignity to those who are abused. I respect Nasser’s talent as much as I am heartbroken by his fate.

“Literature goes beyond revelation of evil: it restores dignity to those who are abused. I respect Nasser’s talent as much as I am heartbroken by his fate.“

4. Why do you think some of the literary world has remained silent on the movement for Palestinian self-determination?

JG: It isn’t for me to judge others. As an independent publisher, I am accountable to no one. I fight for what I believe, and in this case, I personally feel deeply responsible for what Israel is inflicting on Palestine. I am a secular Jew and the only way I can speak out is by using the venues that are available to me. I have been publishing books critical of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians for a very long time. While I am in total sympathy with the present strike, it made little sense to me to turn down an interview with a prison writing program whose perspective on the Palestinian issue is totally aligned with my own. To me, the fact that these questions have been taken up, as a part of a rigorous evaluation, is a sign of change in the right direction. There are different ways to help people see the light.

5. You traveled to occupied Palestine and Israel to visit Abu Srour’s family and also to the Nafha prison in the Negev desert where Abu Srour is now held. Could you describe the lived experience of Abu Srour as a writer inside Israeli prison walls and the impact his incarceration has had on his family and community of fellow writer-activists?

JG: In the book, Nasser describes life in several prisons, as he is transferred from one place to another over the years. But I can’t really speak of Nasser’s personal experience at this moment. When I traveled to the prison in the Negev with his lawyer, I wasn’t allowed to see Nasser. But I wanted him to know I was there. As I waited outside, I was stunned to see a huge menorah standing in front of the highest security prison in Israel. During my trip, I also visited his family. That gave me a sense of how much they are constantly thinking of him. His portrait is on a wall outside their house in the refugee camp, and he is clearly perceived as a deeply missed hero in his community. I felt part of the family, and we took so many photos together. The fact that I am Jewish was totally irrelevant. They know better there. In Palestine, people go straight to the heart of the matter.

6. Abu Srour so beautifully reflects, “We spoke all the languages of pain, but we still had space to smile and laugh at jokes. We preserved a belief in our coming victory and a better life, when our long death would die and we would bury it in the back garden, reciting the poems of victory we had written for the occasion.” How do you feel Abu Srour’s poetry and his writing journey have served as a tool of resistance and hope throughout his incarceration? What are your reflections on the discipline of hope inside prison walls, and how incarcerated writers find ways to hold joy as a site of resistance?

JG: How they can do this is one of the biggest mysteries. I suspect that reading, studying, and searching for meaning, both philosophically and in politics, must give them a sense of deep integrity, in striking contrast to their oppressors, who have sacrificed their humanity to preserve a lie. In the book, Nasser also describes a number of strategies, such as embracing his pain and abandoning life beyond the prison walls, that enable his resilience. He lives in his imagination, which is also the force that generates his poetry and this entire memoir, which he remarkably found a way to share with the world.

“He lives in his imagination, which is also the force that generates his poetry and this entire memoir, which he remarkably found a way to share with the world..“

7. Abu Srour writes powerfully, “Our naked, bleeding breasts exposed the lie about a barbarous East that needed the West to refine its primitive savagery…” Abu Srour also writes about how mythologies of Palestinian history and its people are storied by people in power in Israel and in the West in order to legitimize the erasure of Palestinians and to shape the global public imagination in a particular way. How does your role as a translator strive to resist these mythologies and colonial lenses, and strive to help translate truths to the Western world that can legitimately dismantle these dominant narratives?

Luke Leafgren: As a translator, my job is to give a voice in English to my authors. I endeavor to convey the power of their ideas and the beauty of their language so that it will shine in English as clearly as I experience it in the original Arabic. When the texts of an oppressed people become available in a new language, they disrupt established narratives by showing a culture’s complexity and richness that were inadvertently overlooked or deliberately suppressed.

8. In the genre of prison literature, incarcerated writers are often tokenized and reduced to being experts solely on their suffering and trauma within prison walls and yet you included Abu Srour’s love story. Why did you decide to portray the fullness and complexity of the human spirit beyond incarcerated status?

LL: This book is fascinating because of the way Nasser mixes genres. After a dozen chapters that mix history, autobiography, and sociopolitical analysis, we get a love story told in poetry, dialogues, and letters. This second half of the book is so important because it shows the emotional life of our author. It is fascinating to see how falling in love causes Nasser more pain than anything he had experienced before. It shows that—in prison or not—the heart has reasons that reason doesn’t know. Reading this section, we know exactly how Nasser feels, and that identification is a mark of the literary power of this book.

“When the texts of an oppressed people become available in a new language, they disrupt established narratives by showing a culture’s complexity and richness that were inadvertently overlooked or deliberately suppressed.“

9. Abu Srour writes, “In our lexicon of dignity and worth, the pains of others had no color or smell that distinguished them from our own, for we identified with every speech that rebelled against injustice or supported the not yet triumphant.” How has the writing and movement building of those you publish around the world contributed to or integrated transborder solidarity with other injustices arising in the world, especially around the prison industrial complex across borders?

JG: This is an excellent idea! And you are exactly right, Nasser’s description of the way young Palestinians feel solidarity with other oppressed people around the world shows a path for our own efforts. At Other Press, some authors and titles that come together in this area are Incarceration Nations by Baz Dreisinger, My Brother Moochie by Issac J. Bailey, The Butcher’s Trail by Julian Borger, Life Laid Bare by Jean Hatzfeld, For Two Thousand Years by Mihail Sebastian, Isaac’s Torah by Angel Wagenstein, We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I by Raja Shehadeh, In the Company of Men by Véronique Tadjo, and The Elimination by Rithy Pahn, among others. I have many books on this topic but never thought of connecting them as a series of works of art that transcend the tunnels of horrific abuse and segregation.

10. Abu Srour is one of more than 5,000 Palestinians held in Israeli prisons before October 7, 2023. How has the further incarceration and killings of Palestinian writers and artists since October 7th affected how you both support, resource, and amplify Palestinian voices?

JG: Since October 7, my books on Palestine are more visible than ever, and I speak almost every week in my newsletter about the topic, even when discussing books that have no obvious connection. To this day, I have not received any hate email or things like that. I think the majority of readers are totally aligned with me, even if they don’t always speak out. My hope here is that literature can be truly faithful to its calling and things may change. My dream is to seduce the unconverted. I hope The Tale of a Wall will help reveal that the roots of the present crisis go far beyond the catastrophic consequences of what we are witnessing now. It would be amazing if your interest in The Tale of a Wall could resonate throughout PEN America as a whole.

Nasser Abu Srour was arrested in 1993, accused of being an accomplice to the murder of an Israeli intelligence officer, and sentenced to life in prison. While incarcerated, Abu Srour completed the final semester of a bachelor’s degree in English from Bethlehem University, and obtained a master’s degree in political science from Al-Quds University. The Tale of a Wall is his first book to appear in English.

Luke Leafgren is a translator and lecturer on comparative literature and the Allston Burr Assistant Dean of Harvard College for Mather House.

Judith Gurewich is the publisher of Other Press, a position she has held since 2002. Under her leadership, Other Press has become a highly respected and award-winning publisher of literary fiction and non-fiction.

Deborah Jackson Taffa | The PEN Ten Interview

I could only share my family’s trauma if I told it in context, reminding readers that my elders struggled, not because of a moral failure on their part, but because of societal and governmental pressures.

Kevin Huizenga | The PEN Ten Interview

I like to be productive, and sometimes being productive means taking an idea you thought up in a previous story, and expanding on it, or turning it around to look at it from another angle.

Michael Arceneaux | The PEN Ten Interview

I’m very clear about what I want to say and how I want to say it when I try to sell a book. You either believe in it or you don’t

Lisa Grunwald | The PEN Ten Interview

I was looking for a time in American life when things seemed as passionately divided as they do now.