The PEN Ten: An Interview with Michelle Gallen

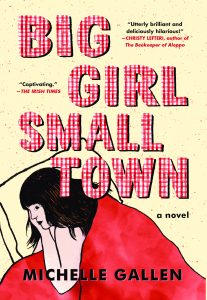

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jaime Gordon speaks with Michelle Gallen, author of Big Girl, Small Town (Algonquin Books, 2020).

Photo by Declan Gallen

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I can remember reading Funnybones as a wee child in school, and the opening to that book transported me from the classroom and drew me down into that dark cellar like a magnet. It’s one of the best openings to a book I’ve ever read, and it still captivates me.

2. Why do you think people need stories?

I think humans—like many other creatures—like to learn by doing and feeling things. At school, I discovered I liked learning facts but also wanted to “feel” what they meant. Reading facts about the Second World War—such as which countries were invaded when, which general committed what atrocity, how many people died—had less impact on me than reading The Diary of Anne Frank. I’m also strongly influenced by my family’s seanchaí tradition. When we got together, the older generations told stories about the things that had happened to our family and our neighbors—stories that often intersected with historical events. I heard the same stories over and over again, which gave me a strong sense of who I was and where I belonged. Stories told in books opened the whole world to me and continue to give me a much bigger sense of where I fit in on this planet we share with so many other life-forms.

3. What is your favorite bookstore, or library?

I studied English literature at Trinity College Dublin, and I had the opportunity to read in the world-famous Long Library. It’s a beautiful, somewhat intimidating space that was used as inspiration for the library in Hogwarts. But I’m much more attached to the rather drab public library I used growing up. My mother drove me and my five siblings there once a week. I’d read all the children’s books by the time I was 10 years old, so my mother took adult books out for me on her card (the librarians were strict women, who did not think the James Herbert and Stephen King novels I was obsessed with were suitable for kids). I would never have had the opportunity to study in the Long Library had I not gorged on books from our little local library.

“I’m strongly influenced by my family’s seanchaí tradition. When we got together, the older generations told stories about the things that had happened to our family and our neighbors—stories that often intersected with historical events. I heard the same stories over and over again, which gave me a strong sense of who I was and where I belonged. Stories told in books opened the whole world to me and continue to give me a much bigger sense of where I fit in on this planet we share with so many other life-forms.”

4. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I’m missing London at the moment, so reading novels set in the pre-lockdown city has been a comfort and an escape. I’ve just finished reading Girl, Woman, Other by Bernadine Evaristo and have started Hot Stew by Fiona Mozley. I absolutely loved her first novel Elmet, which was longlisted for the Booker Prize. I love how Mozley tackles the big questions around ownership, wealth, and inheritance. After this London-based binge, I’ve planned a change of scenery with Earthlings, which is the latest novel by Sayaka Murata to be translated into English. I adored her book Convenience Store Woman, seeing strong parallels between her protagonist Keiko who has worked 18 years in a store, and Majella, the protagonist of Big Girl Small Town. I love books that plunge me into worlds so I can see, feel, and smell the smallest details.

5. What advice do you have for young writers?

The advice I have for young writers applies to middle-aged writers and elderly writers too: Write as much as you can as often as you can. I’ve written hundreds of thousands of words that no one will ever see—it feels to me a bit like being a gymnast or ballerina, years of practice are required, alone or with a mentor, before your words get the chance to “perform.” I also think it’s very important to read widely in order to learn your craft. I’m a big reader, which has given me a good instinct for what elements make a great book, but I’ve only recently understood how important it is to analyze how books are structured, how they’re crafted, why they succeed or fail. It’s like suddenly seeing architectural types and details instead of just buildings. But the most important thing a writer can do is to live mindfully with curiosity and kindness, to participate in life, and to listen to—and observe—as many people as you can. That’s how I gather the raw material for a creative work.

6. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

I read for pleasure and often for relaxation, so I rarely look to be excited by a writer. I want to be immersed in the world a writer creates and have it leave an imprint on me. I’d love to see what Irish author Anna Burns does after winning the Man Booker Prize with Milkman. I can’t wait to get more of Irish writers Mike McCormick, Sara Baume, June Caldwell, Oisín Fagan, Niamh Campbell, Louise Kennedy, and Wendy Erskine. Further afield, I’m watching Sayaka Murata, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, Candice Carty-Williams, John Harrison, Elizabeth Strout, Daisy Johnson, Kiley Reid, Patricia Lockwood, and Anthony Doerr.

“The most important thing a writer can do is to live mindfully with curiosity and kindness, to participate in life, and to listen to—and observe—as many people as you can. That’s how I gather the raw material for a creative work.”

7. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Oh, that’s a hard question! I’d like to meet so many writers: Jean Rhys, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Margaret Atwood, Karl Ove Knuassgaard, Shakespeare! But I think the writer who would teach—and perhaps frighten—me the most is Elena Ferrante. I’ve read all her books and am obsessed with how she deconstructs the poverty and politics of working-class neighborhoods and how she captures the love/hate element of some female relationships. Her depictions of domestic and gang violence are exquisite and terrible. I’d love to walk through her books with her and learn about her creative process: How did she find her narrator’s voices? How does she write with such control? Who does she love who is writing now?

8. Routines are very important to Majella, the main character in Big Girl, Small Town. Do you have any specific writing routines?

My life is very routine based right now—it has to be with kids. Routines are a deep comfort for me—they reduce my anxiety. But I find it harder to be creative when in thrall to my children’s routines and writing around their needs for food, education, exercise, and love. I have to write when someone is playing the drums, or crying because someone else used “their” cup. Before children, I had the time to write every day and to daydream deeply—which is something that can drop me into a character or a room or a street. Back then, I wrote first thing in the morning, without fearing the interruption of the pitter-patter of small, insistent feet upon the stairs. After my day job, I’d focus on the admin of writing—submitting short stories, following up on queries.

for me—they reduce my anxiety. But I find it harder to be creative when in thrall to my children’s routines and writing around their needs for food, education, exercise, and love. I have to write when someone is playing the drums, or crying because someone else used “their” cup. Before children, I had the time to write every day and to daydream deeply—which is something that can drop me into a character or a room or a street. Back then, I wrote first thing in the morning, without fearing the interruption of the pitter-patter of small, insistent feet upon the stairs. After my day job, I’d focus on the admin of writing—submitting short stories, following up on queries.

I’d spend uninterrupted hours in my head with my characters and more hours hanging out with other writers, reading their work, having them read mine. We’d chew over the words we’d written, talking about the things we’d lived through. Many writers say, “Oh, you can write during 10 minutes at the kitchen table while the dog is chewing a sock and the cat is eating from the bin and your kids have a flour fight.” I guess many writers can, but I find noise and constant distraction draining. I can write through it all, often well, but it’s not the deep pleasure of wallowing in hours of alone time. But if the pain of raising kids is measurable, the pleasure is immeasurable. It is sheer joy watching them discover the world: reading books with them, painting pictures, watching movies, and discovering food. They have filled me up in ways I’ve yet to process.I see myself like a cow years from now, happily chewing over the cud of these frenetic years, digesting more of their goodness in quieter times.

“I can write through it all, often well, but it’s not the deep pleasure of wallowing in hours of alone time. But if the pain of raising kids is measurable, the pleasure is immeasurable. It is sheer joy watching them discover the world: reading books with them, painting pictures, watching movies, and discovering food. They have filled me up in ways I’ve yet to process.”

9. Which parts of this book were the most difficult to write? Which were the easiest?

The first 70,000 words were written in a glorious rush one November when I signed up to Nanowrimo. The next 40,000 words took three years to find their way onto the page. Then it took several months to reduce the book back down to 100,000 words. I obsessed over small details that mean a lot to me, such as the foxes, the circumstances around Uncle Bobby’s death, and the rumors around Majella’s father’s disappearance. I wanted to give enough detail that some readers might figure out the truth behind the rumors and facts as they appear to Majella, while other readers will feel as frustrated and confused as I did for years in Northern Ireland—always feeling that someone else had all the pieces of the puzzle but was refusing to put them together. I feel Majella has most of the pieces of the puzzle—some of which she refuses to piece together. But someone in her life has been withholding a final key piece, without which she’ll never understand. You can go to your grave not understanding.

10. What other recent novels do you see Big Girl, Small Town as being in conversation with?

- The Lonely Passion of Miss Judith Hearne by Brian Moore, which is an exquisite portrait of a genteel alcoholic spinster woman who is spiraling deeper into loneliness and alcoholism. Everything Moore wrote was wonderful. But I loved the way he put an ordinary woman—her sorrow, but no great drama—at the center of a very compelling book.

- Ripley Bogle, written by Robert McLiam Wilson when he was 26, was my first introduction to a bawdy, brilliant, anarchic Northern Irish novel. It gave me great confidence that anti-heroes could be just as compelling as typical heroes.

- Milkman, written by Anna Burns, won the 2018 Man Booker Prize. I didn’t read it until the summer I was editing Big Girl, Small Town, so I can’t say it influenced the book directly, but I feel both books are part of a conversation female writers are having about the experience of being identified as “female” during and after the conflict in Northern Ireland, and how that dictates how you are expected to live your life.

Michelle Gallen was born in County Tyrone in the mid-1970s and grew up during the Troubles a few miles from the border between what she was told was the “Free” State and the “United” Kingdom. She studied English literature at Trinity College Dublin and won several prestigious prizes as a young writer. Following a devastating brain injury in her mid-twenties, she co-founded three award-winning companies and won international recognition for digital innovation. She now lives in Dublin with her husband and kids.