The PEN Ten: An Interview with Kiese Laymon

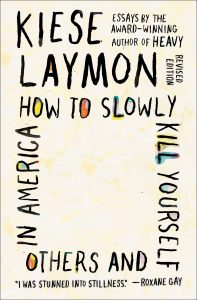

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jared Jackson speaks with Kiese Laymon, author of How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America (Simon & Schuster, 2020).

1. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

1. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I’m shamefully inspired by the reality of death—earning death, as Baldwin phrased it. I assume death is near for me, my family. So, when I don’t want to write and read, I remind myself that we will all be gone soon. It’s unhealthy. But it’s why I write and revise daily.

2. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about?

Rae Paris’s The Forgetting Tree is just phenomenal art for the head and heart and memory.

“I’m shamefully inspired by the reality of death—earning death, as Baldwin phrased it. I assume death is near for me, my family. So, when I don’t want to write and read, I remind myself that we will all be gone soon.”

3. How can writers affect resistance movements?

We can write to folks who are rarely centered in American literature, and we can ask organizers how we can most be of service.

4. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

Heavy was the most daring thing I’ve ever made. And I wish I could take parts of it back twice a day.

5. What advice do you have for young writers?

Commit every day to doing whatever it takes to become the writer you want to become, while committing to being a better person than you are a writer.

6. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

I’m really excited by so many including Deesha Philyaw, Nate Marshall, Brittany Means, B. Brian Foster, and Regina N. Bradley today.

“I’m working now on accepting that home might really be a mobile metaphor. Before, I knew Mississippi was home. It is. But I think I’m heavy enough to hold homes in my chest, on my back. When I started writing this, I just wanted to make it back to Mississippi. Now, I just want to be better at love and free.”

7. The title of your essay collection is How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. In the author’s note, you explain that in 2009, when you were “getting worse at being human,” you first wrote the sentence, “I’ve been slowly killing myself and others close to me.” Both the sentence and book’s title set quite the tone. Tone is one of the most crucial and beguiling aspects of storytelling. How would you describe the tone of the book? How did it bend from essay to essay? Did you want to leave readers with the same tone by the end of this revised edition as you did with the first?

7. The title of your essay collection is How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America. In the author’s note, you explain that in 2009, when you were “getting worse at being human,” you first wrote the sentence, “I’ve been slowly killing myself and others close to me.” Both the sentence and book’s title set quite the tone. Tone is one of the most crucial and beguiling aspects of storytelling. How would you describe the tone of the book? How did it bend from essay to essay? Did you want to leave readers with the same tone by the end of this revised edition as you did with the first?

I love this question. The tone of the first one was sort of like ascendant bombast with lots of voices because it was so linear. This revision is still filled with lots of voices, but the tone is much more whispery, scared, to tell you the truth. It’s a call and response book that ends on a call into the ether. So, it’s more of a plea than the first one to me.

8. Earlier this year, you bought back your first two books so you could revise and reissue them. How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America is one of the two books, the other being the novel Long Division. Revision has been a refrain in your life both as a writer and a person. Revision provides the opportunity to step back and re-envision. It’s an opportunity to examine your ideas and how you expressed your ideas. What were your intentions in revising this collection? In what ways have you revised as a person between the original publication and this recent one, and how have those life revisions affected you as a writer?

Scary question. I wrote that first book not thinking I’d be alive if anyone read it. That book got me to Heavy and the new projects. So, I’m working now on accepting that home might really be a mobile metaphor. Before, I knew Mississippi was home. It is. But I think I’m heavy enough to hold homes in my chest, on my back. When I started writing this, I just wanted to make it back to Mississippi. Now, I just want to be better at love and free.

“Don’t ask anything of your characters or your nation or your people that you won’t ask of yourself. That’s the hardest part of this art creation shit. We have to be tough and tender with ourselves.”

9. Music finds its way throughout the collection—be it talking about N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police” or a meditation on the Atlanta duo Outkast in the essay “Da Art of Storytellin’ (A Prequel).” For me, one of the defining aspects of your writing is your voice—the musical and distinct quality of your writing in which I can hearyou as I read. In the aforementioned essay, you write, “Literary voices are built and shaped—and not just by words, punctuation, and sentences, but by the author’s intended audience and a composition’s form.” What’s your relationship with sound and narrative? Who is your intended audience, and does it shift from project to project?

I used to be obsessed with repetition. Now, I’m super obsessed with making the unexpected rhetorical move feel pleasurable. That’s really the opposite of repetition. It’s a lot harder, too. Folks find pleasure often in a hook, a refrain, something that feels like home. I’m working on making readers—those who aren’t usually written to—find pleasure in new paragraph shapes, and sounds. My most valued audience is always the Black southern folk who made the traditions I’m a part of. They read. They hate reading. They write. They hate writing. I want them to feel loved and agitated by my work.

10. The writing and subject matter in this collection, and your work in general, is particularly vulnerable. You write to friends who write to you, you write to your uncle, and you have an essay in the form of email exchanges with your mother. In the latter, an essay titled, “An Essay in Emails,” you admit to not being ready to answer certain questions honestly. In response to a question about what can and cannot be shared in this essay, your mother—who does not want certain details revealed—asks, “Why would you want strangers without our best interest at heart to see that?” Considering a former course description of mine, I wonder: What are the questions you consider when narrating vulnerability—emotional, physical, political, socioeconomic? What role can a first-person “I” play in writing about the lives of other people—when is it necessary, and when does it intrude?

I think we have to start with what we want to lie about. Then, we have to write through, below, on top of that. And when it gets too hard, we can write about the times we’ve actually told or accepted the truth. And then, we have to ask the same questions of our secondary characters, whether we’re writing fiction or nonfiction. Don’t ask anything of your characters or your nation or your people that you won’t ask of yourself. That’s the hardest part of this art creation shit. We have to be tough and tender with ourselves.

Born and raised in Jackson, MS, Kiese Laymon, Ottilie Schillig Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Mississippi, is the author of the novel Long Division and the memoir Heavy.