The PEN Ten: An Interview with Cynan Jones

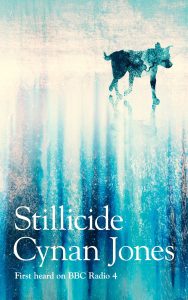

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Jaime Gordon speaks with Cynan Jones, author of Stillicide (Catapult, 2020).

Photo by Bernadine Jones

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe. I had other “favorite books” when I was young, but this was the first to truly transport me. I was seven years old.

I guess I intuited that to read is to pass into another world. And the world of this story had a recognizable landscape. It had forest, streams. A big house I could equate to my grandparent’s farmhouse (though it was humble, it was giant to me). Talking animals and mythical creatures.

This book’s pages were populated with the same elements my seven-year-old imagination populated the world around me with. It gave me sanction to make-believe. I’ve never recovered from that.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Historically, I’ve written in intense bursts, after a story has formed in my head. My ideas generally come from the landscape, then orbit each other in different states of readiness. When an idea finds form, it demands to be written. When that moment comes, I write as if I’m watching. I put a working draft of the story down as simply and strongly as I can. Then, the hard work starts.

Stillicide, however, was written differently. It was a commission, there were deadlines, and other people wanted input. I had a nine-month-old baby, a two-day-a-week mentoring job, and other travel and teaching commitments. My go-to process wasn’t possible. I gave the commission three days a week and took weekends off. I trusted the fact that the story had been swirling around my mind for a long time. Individual pieces had no time to form fully then announce themselves; I just had to sit down and go and fetch them out of my brain.

Regarding momentum and inspiration, for Stillicide, it came from the pressure and the thrill of the world I was writing about.

“My ideas generally come from the landscape, then orbit each other in different states of readiness. When an idea finds form, it demands to be written. When that moment comes, I write as if I’m watching. I put a working draft of the story down as simply and strongly as I can. Then, the hard work starts.”

3. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

The last book I finished was Paul Klay’s brilliant short story collection Redeployment. Reading that coincided with a lot of mental noise, and I’ve bounced off a few titles since. In the end, I’ve done what I always do when I can’t find the right thing to read. I’ve gone back to Sherlock Holmes. I’m halfway through A Study in Scarlet.

4. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

I’d like to say the story itself shapes my writing, but inevitably, we’re drawn to tell stories our identity attracts us to. My identity is very much determined by the place I grew up and still live in. With my first novel, The Long Dry, I recognized I could write stories about this landscape and community. It was a breakthrough.

While I like to think I’ve done something new in each of my books, or with each short story I write, readers and critics find my “identity” throughout them. It’s probably important for me not to analyze that too much. A writer can get too self-conscious.

5. What advice do you have for young writers?

Writing is not an art, it’s a craft. Like playing the violin, or hitting a baseball, or throwing a clay pot. What you do with the craft is the art.

However good your imagination is, you’ll fail your ideas if you don’t have the skill to write them down as strongly as possible. Therefore, practice. Go through the frustration of bungling your story, failing your characters, mauling your descriptions. Every sentence you write helps build skill. Be patient and relentless. Most of all, read. Read and read.

“Writing is not an art, it’s a craft. Like playing the violin, or hitting a baseball, or throwing a clay pot. What you do with the craft is the art.”

6. Why do you think people need stories?

Much of what we manage is the result of belief in a story we’ve been told or that we’ve told ourselves. We are fundamentally built to navigate the world by applying fictions to it. That’s incredible. Stories are both the route into and out of horror and hope, for better or for worse. We want to throw ourselves under spells.

7. What inspired you to tackle the climate crisis in Stillicide? Do you consider it to be a work of science fiction? Why or why not?

7. What inspired you to tackle the climate crisis in Stillicide? Do you consider it to be a work of science fiction? Why or why not?

I don’t see Stillicide as “tackling” the climate crisis, as such. The crisis is. The state of the climate is the matrix into which the world of the story is bedded.

There’s a lot of science in it, and there’s a lot of fiction. It was amazing, though, how many times I “made something up” only to find out it was already fact—particularly in the early stages in some drafts and ideas that didn’t make the final cut. Floating farms, for example. Landfill miners. Even harvesting icebergs, which I “invented” chiefly because of the extraordinary image it delivered.

I’ve done huge amounts of research for previous books, but there was no time for that with Stillicide. My leaps of imagination, into a world not too far in the future, frequently turned out to be very real possibilities. Not least, the disease that Branner’s wife is dying of. This was more at the forefront of early drafts (2018), but I chose not to give it such heft as work went on. I’m glad I made that choice, given the situation now.

8. What aspects of this book were the most difficult to write? Which were the easiest?

While Granta decided at an early stage to publish the collection, Stillicide was originally radio-commissioned. I had to quickly convert the more challenging aspects of that into creative rules. The BBC was paying me to write a series of 15-minute interrelated but standalone stories for voice. They had a say in the final product. Each story would be nuanced by the actor who read it and the producer. The important thing was not to use any of that as an excuse, to respect the remit of the original audio format, and at the same time produce a book I could look in the eye.

Given that, the book only differs from the radio stories in some small but essential ways. Most notably, I kept the original opening, which was considered too brutal for a Sunday evening radio slot, and one story—Potato Water—is shorter because the longer radio version wasn’t ready by the time Granta needed the manuscript signed off.

Coming up with ideas for the stories was the easiest part, and the pressure of delivery deadlines helped that process.

“I don’t see Stillicide as ‘tackling’ the climate crisis, as such. The crisis is. The state of the climate is the matrix into which the world of the story is bedded.”

9. Did you come up with the plot or the experimental structure of Stillicide first? How do the two interact and augment each other?

The plot and structure are incontrovertibly linked. The title itself signposts that. The world of Stillicide had been in my mind for a long time, and from an early stage, I saw the narrative forming as a set of individual pieces that would pool together to create a wider story. When BBC Radio 4 asked me to pitch 12 stories that would be effective if heard in isolation—but which would accrue to tell a bigger story—my instinctive notion of how this narrative should be structured was a match.

The task in the initial stages was to settle on a dozen pieces that, together, would tell a coherent “story,” but the commission dictated there could be no dominant narrative thread. Stories should work in whatever order they might be heard. I therefore had to build the wider narrative differently, by accumulation. The “plot” became an ellipse. The real through line, a love story.

The big decision was to resist turning the piece into a “thriller.” Keeping the original opening for the book—so the reader knows right from the start what choice Branner makes. In choosing this, not only do the plot and the structure interact and augment one another, but each story in the collection interacts with and augments the others to collect and deliver the emotional power of the book as a whole.

10. How do you strike a balance between writing about larger existential threats, like climate change, and the day-to-day trials of the human condition, such as love?

I keep my eye on the individuals who carry the story. History is backdrop. There will always be some over-threat against which we persevere, adapt, cope, rile, rage. But ultimately, we must get on with the mundane tasks that keep us going.

I’ve not thought about it before, but seeing your question, perhaps striking the balance you ask about comes from my belief that the day-to-day trials of the human condition, such as love, are not trials. They are imperatives. It’s how a person gets on with those things in the face of threat or opportunity that provides the most insight into the human condition. This, then, is where the story truly lies.

Cynan Jones was born in 1975 near Aberaeron, Wales, where he now lives and works. He is the author, most recently, of Stillicide. He has won a Society of Authors Betty Trask Award, a Jerwood Fiction Uncovered Prize, the Wales Book of the Year Fiction Prize, and the BBC National Short Story Award. His short fiction has been widely published in anthologies and publications including Granta and The New Yorker.