The PEN Ten: An Interview with José Vadi

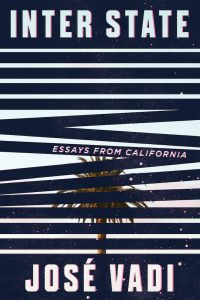

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with José Vadi, author of Inter State: Essays from California (Soft Skull Press, 2021).

Photo by Bobby Gordon

1. How does your writing navigate truth? How has writing about history revealed new ways of thinking about truth for you?

I think writing about my history and those histories I’ve inherited about my family from different family members has allowed me to embrace the missing gaps of the collective familiar timeline and accept the shards of memories for what they are. By embracing a mosaic and not a seamless line, it allows for ongoing “truths” added as they reveal themselves over time.

2. How, for you, has writing about history revealed new ways of thinking about truth as a concept, especially in its relation to storytelling and memoir?

Truth itself is a sort of loaded word. But writing about history and documenting my own living history in the Bay Area revealed new ways to embrace the mistakes (like not finding a skate spot in “Spot Check”) as well as navigating my reaction to the world around me (like navigating the old woman’s “white man’s back” comments in “Inter State”). By engaging with new parts of California, I created new historical records for myself in relation to this state that I then translated onto the page. This transferring includes daydreams about my grandfather burning down crops with joints I know he’d never smoke, or argumentative detours that circle back to the subject at hand.

The “truth” I was painting was one that embraced confusion, uncertainty as much as inquiry, curiosity, and the physical pursuit not for a ‘truth’ necessarily, but to bear witness to whatever scenario or context hosted whatever known histories preceding my arrival.

“I think writing about my history and those histories I’ve inherited about my family from different family members has allowed me to embrace the missing gaps of the collective familiar timeline and accept the shards of memories for what they are. By embracing a mosaic and not a seamless line, it allows for ongoing ‘truths’ added as they reveal themselves over time.”

3. How can writers affect resistance movements?

That depends on the resistance movement in question, and the needs of that movement and the constituents it represents. A writer’s work may not be necessary for a specific cause—maybe they could be of better use raising awareness or simply listening and educating themselves. I think writers, like all humans, should be aware of the communities they are depicting in their prose, their own place as writers in the communities they inhabit, and to always question whether their involvement in any movement is centered around artistic career advancement or actual care.

4. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

I went from writing first thing in the morning to very late at night. But I think what’s changed the most is my ability to best utilize whatever time I do have to write to its fullest potential. At Mills College, writer and professor Micheline Marcom would frequently tell us fledgling grad school writers, “Once you find your voice, it’ll be quicker to access it when you sit down to write.” That, thankfully, has proven true over the course of writing Inter State.

5. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know?

Fernando Flores’s Tears of the Trufflepig. The second half of this novel took me to a part of the Rio Grande Valley along the Mexican border that can only be compared to a psychedelic experience, specifically what it feels like to be on psychedelics—time, like lights, are stretched; an odd serenity; an underlying intrigue—which is how I felt reading the book. It’s an amazing novel for anyone interested in how rare art curation meets drug trades and their culinary counterparts—in this odd but truly relatable universe Flores creates.

To discover through interviews that this effect was by design—and allowed Flores to showcase the effect of living, working, and growing up in this part of Texas and the Mexican border—was really remarkable, and made me appreciate even more this novel and its relationship to the fictional and literal, let alone psychedelic, worlds it seamlessly creates and embodies.

“The ‘truth’ I was painting [in Inter State] was one that embraced confusion, uncertainty as much as inquiry, curiosity, and the physical pursuit not for a ‘truth’ necessarily, but to bear witness to whatever scenario or context hosted whatever known histories preceding my arrival.”

6. What is one critique of your work that you have really learned from?

My entire working relationship with my editor Mensah Demary at Soft Skull Press/Catapult has been a huge learning experience, and this book is the product of that relationship. Inter State was an email thread of multiple essay drafts that, starting in 2016, privately and slowly took the shape of a manuscript, and really took shape after the namesake essay was first submitted in 2019. Throughout the process, Mensah encouraged me to utilize research that aligned well with my personal experiences. That was key—allowing a symbiotic relationship to exist between personal narrative and research, and to allow one not to destroy the other. This self-awareness allowed me to weave these strands with a sense of movement, space, navigation, and the prose that reflects all those things.

7. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

I try not to read anything too close to what I’m specifically writing about—I didn’t read a lot of California memoirs while writing Inter State, for example. I tend to read fiction more than anything and follow certain writers, presses, and journals as much as I can: Deep Vellum, Soft Skull Press / Catapult / Counterpoint Press, New Directions Publishing, Passenger Pigeon Press, and The Baffler, to name a few.

I enjoy César Aira and Percival Everett’s works greatly. Photography zines like Hamburger Eyes are always inspiring.

8. Over time, retellings of history that were once veiled rise to the surface, adding codas to narratives once accepted as irrefutable. This applies to family histories as well as histories of communities. You write, “In my thirties, some family members see me as ripely capable of receiving and comprehending those lesser-known family histories: the girlfriends that existed before the tías that raised me.” What was it like to absorb so many new perspectives of the past at once—from stories about your family to that of California, a land you feel so connected to?

8. Over time, retellings of history that were once veiled rise to the surface, adding codas to narratives once accepted as irrefutable. This applies to family histories as well as histories of communities. You write, “In my thirties, some family members see me as ripely capable of receiving and comprehending those lesser-known family histories: the girlfriends that existed before the tías that raised me.” What was it like to absorb so many new perspectives of the past at once—from stories about your family to that of California, a land you feel so connected to?

I have to remember I recorded my grandfather nearly 15 years ago—even then, I demonstrated a desire to absorb and document perspectives of the past. The few new revelations I did receive were a trip because they were delivered in super casual, out-of-the-blue fashions. But however surprising, I think it just helped further humanize the many people my family members were before my existence, and how that helped shaped whatever relationship we have or didn’t get to have with one another.

I never met my grandfather on my dad’s Puerto Rican side nor my grandmother on my mother’s Mexican side, but given the stories I’ve heard from them and other members of our family, in a way, they feel as alive as those who I knew and have already passed, like my grandfather Antonio himself.

“I feel that criticism and the ability to be critical is an important part of any healthy relationship. Just as your close friends should be the first to call you out, so too should a writer be able to raise awareness around those issues they experience and observe closely across their lifetime.”

9. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

One of the most surprising things I learned while writing Inter State were the very recent incidents of arson directed at housing developments for seasonal farmworkers legally in California via H-2A work visas. I cited some incidents that occurred near the Central Coast and Salinas Valley. These are some of many examples of ongoing racist violence and anti-immigrant sentiment that Mexican and Central American farmworkers of any citizenship status face in California.

10. Publishers Weekly aptly described Inter State as “part love letter, part indictment,” capturing the evolving physical and cultural landscape of California. It’s clear from your historical knowledge and your ongoing curiosity that you harbor a great deal of love for your home state. Yet, you don’t shy away from expressing anger—at transformations brought on by the tech industry, by the rise of environmental disasters, or by the bourgeoning inequality (that has quite a long history in California). Why is it important to not let what we love slip past our radar of criticism? Are there people who have tried to tell you that dissent and love cannot coexist?

I feel that criticism and the ability to be critical is an important part of any healthy relationship. Just as your close friends should be the first to call you out, so too should a writer be able to raise awareness around those issues they experience and observe closely across their lifetime. I frequently think of the beautiful film The Last Black Man in San Francisco and the quote regarding San Francisco: “You can’t hate it unless you love it”—and that’s how I feel about my relationship with California.

José Vadi is an award-winning essayist, poet, playwright, and film producer. Vadi received the San Francisco Foundation’s Shenson Performing Arts Award for his debut play, a eulogy for three, produced by Marc Bamuthi Joseph’s Living Word Project. He is the author of SoMa Lurk, a collection of photos and poems published by Project Kalahati/Pro Arts Commons. His work has been featured by PBS NewsHour, the San Francisco Chronicle, and The Daily Beast, while his writing has appeared in Catapult, McSweeney’s, New Life Quarterly, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s Open Space, and Pop-Up Magazine.