The PEN Ten: An Interview with Marisel Vera

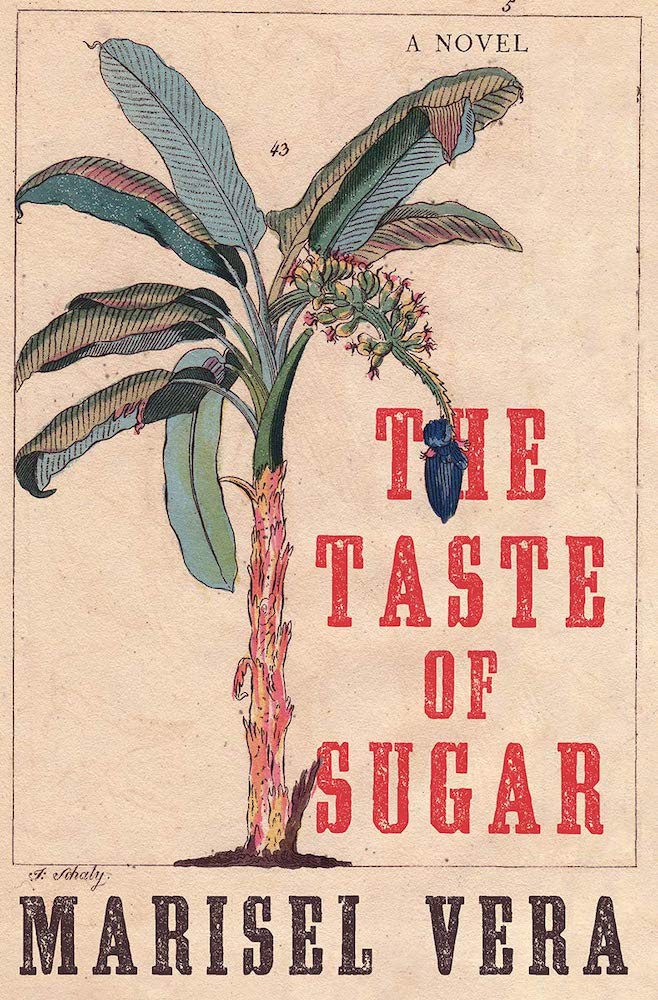

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Marisel Vera, author of The Taste of Sugar (Liveright, 2021).

Photo by Wes Carrasquillo

1. Why do people need stories?

People need stories for all sorts of different reasons—to understand others, different cultures, and even to learn about themselves. Not only do we need to read a variety of stories, we all need to tell stories to each other and to listen when people share their stories with us. We are always changed, even if only a little, by stories.

The stories that my parents told me, especially my mother, helped train me to become a storyteller. Mami’s stories helped me to imagine the jíbaro life up on a mountain that was so different from my own life en el barrio. When she told us that we should be grateful to have rice and beans for dinner because there were times when she and her family were hungry despite her father being a farmer, I imagined myself in her place, barefoot and hungry. I was lucky to hear my mother’s stories, because although I was a voracious reader from a very young age, I didn’t read about any Puerto Rican girls growing up en el barrio.

For many Puerto Rican readers of The Taste of Sugar, reading about people like their ancestors is both a revelation and a celebration. A reader said that after reading the book, he understood the men in his family. Another reader told me that for the first time, she felt seen. Puerto Ricans don’t often read about themselves in novels. It’s extremely important that we see ourselves in stories written in the English language because ever since the United States made Puerto Rico a colony in 1898, the U.S. government has been trying to erase our identity, our culture, our language, and our history. We, Puerto Ricans, must claim the historical truth of our ancestors and our homeland that we can learn about through stories.

“It’s extremely important that we see ourselves in stories written in the English language because ever since the United States made Puerto Rico a colony in 1898, the U.S. government has been trying to erase our identity, our culture, our language, and our history. We, Puerto Ricans, must claim the historical truth of our ancestors and our homeland that we can learn about through stories.”

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

If you were to read the fact that 5,000 Puerto Ricans migrated to Hawaii in the early 1900s to work in the sugar plantations, you’d probably think, “Oh, 5000, that’s a lot of people,” and most likely, you’d soon forget about it. But if you read about Vicente Vega and Valentina Sánchez in The Taste of Sugar and how they lose their coffee farm due to circumstances beyond their control—the 1898 U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico during the Spanish American War, the policies and tariffs that the American military government imposed on Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans, and the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane that ripped up most of Puerto Rico’s coffee trees—tossing them aside like matchsticks, you’d remember. And you might care.

The events in The Taste of Sugar are still factual, but you might have a deeper understanding of the real impact that U.S. colonialism inflicted on Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans through the fictional story of a young coffee farming couple. You might get to know Vicente and Valentina, grow to care about them, maybe even love them. You go along with them on the journey and experience the hardships that the Puerto Rican migrants experienced at the mercy of the American sugar planters, who treated them like cattle, rather than people. You feel for them because you see them as human beings who love and hope and dream the same way you, the reader, loves and hopes and dreams. This is the beauty, the magic, the grace—the gift of the novel. The “real” world would be a much better place if we all read “fictional” novels, especially if we gave ourselves over to stories written by writers unlike ourselves, writers from other cultures—from other countries.

3. What was the first book that made an impact on you?

Down These Mean Streets by Piri Thomas shook me when I was 16 years old. Finally, after the hundreds of books I’d read by then, here was finally a book about being a Puerto Rican in a big city, living in two cultures and two languages and not belonging to either. I could relate, even though Piri wrote about being an Afro-Puerto Rican in New York City during the 1960s, while I was a light-skinned Puerto Rican girl growing up in 1970s Chicago.

Down These Mean Streets is a gritty story that tells how Piri’s life was especially difficult because in his family, everyone was light-skinned except for his father and him. We all know that the reality of the world we live in is that life is easier for you if you aren’t Black. Down These Mean Streets was the first book I read about being Puerto Rican, about what it is like to live in a society that disdains you or even hates you and wishes you weren’t there.

“The events in The Taste of Sugar are still factual, but you might have a deeper understanding of the real impact that U.S. colonialism inflicted on Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans through the fictional story of a young coffee farming couple. You might get to know Vicente and Valentina, grow to care about them, maybe even love them. . . . This is the beauty, the magic, the grace—the gift of the novel.”

4. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

When I begin a new novel, I choose something that really intrigues me, that I’m willing to give several years of my life exploring and thinking about. I conduct extensive research at the same time that I’m writing the book, and that helps keep me fascinated. In this way, calamities, political upheavals, and tragedies are good for a writer. The details I learn help me to create the world of the novel. My love for history—especially Puerto Rican history—and my need to write about Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans inspire and motivate me every day because I believe my stories are needed by Puerto Ricans like me.

I envy writers who are able to write detailed synopses with the plot all planned out, with character lists filled with descriptions, etc. Each time I’m about to start a new novel, I try to be that writer, but after 10 minutes, I realize, yet again, that I can’t be that writer because I don’t want to be that writer. For me, plotting is incredibly tedious, and it takes the fun out of writing.

People are always showing up when I’m writing, uninvited the way Puerto Ricans are used to. They appear, wanting to take me somewhere, demanding that I hear them—that I tell their stories the way they want their stories to be told.

In The Taste of Sugar, Raúl Vega, father of Vicente, came to me one day and said, “I want to tell you about the one and only time I fell in love.” For days, I tried to ignore his demand, but if you’ve read The Taste of Sugar, then you know that Raúl Vega is not the kind of person that will accept no for an answer. Finally, I agreed to a single page, and he left me alone after that.

“People are always showing up when I’m writing, uninvited the way Puerto Ricans are used to. They appear, wanting to take me somewhere, demanding that I hear them—that I tell their stories the way they want their stories to be told.”

The story comes to me in bits and pieces, and often in no particular order, which makes structuring the novel a challenge. When I first begin a novel, I only have a very vague idea of the story that I am writing because it is revealed to me in revision. In my daily writing, strangers turn up, and things happen that I could never have planned. It’s exhilarating and risky, even a little scary, like jumping without a net to catch you—I love that. With every draft, I discover what I want to say and why it’s important to say it. In The Taste of Sugar, I thought the novel was about Puerto Rican coffee farmers losing their land and migrating to Hawaii to work in the sugar plantations, but with revision, I realized that it was really about colonialism.

For The Taste of Sugar, when I learned that 5,000 Puerto Ricans went all the way to Hawaii during a time before plane travel, I had to learn why. What was going on in Puerto Rico? I learned that two devastating calamities—the 1898 U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico and the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane—were primarily responsible for this major exodus, the first in a series of government-sponsored migrations.

5. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

Back in 2015, I wrote in The Taste of Sugar about the devastation that the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane inflicted on Puerto Rico and the United States’ government’s callous indifference and inadequate aid to the Puerto Rican people. When Hurricane Maria in 2017 devastated Puerto Rico, the U.S. government and President Trump treated Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans with similar contempt. It was shocking in its eeriness. I went around saying, “Ay bendito, it’s just like Hurricane San Ciriaco.” More proof that after over a hundred years of being a U.S. colony, the United States doesn’t really give a damn about Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans.

6. The Taste of Sugar is not singular among your works that explore the particular burdens that Puerto Ricans and members of the diaspora have faced throughout history. Why is it important for you to write about the experiences of Puerto Ricans and how they figure in American and world history?

6. The Taste of Sugar is not singular among your works that explore the particular burdens that Puerto Ricans and members of the diaspora have faced throughout history. Why is it important for you to write about the experiences of Puerto Ricans and how they figure in American and world history?

While my mother was the main storyteller in our immediate family, I learned about yearning from my father. He left Puerto Rico, like a million other Puerto Ricans, because there weren’t (and still aren’t) jobs on the island. Papi worked on the assembly line in Chicago factories most of his adult life, and when he died in his early 50s, my brother and I attributed it to the noxious fumes from his work as a welder.

One of the reasons I write is that I’ve always felt the injustice of the circumstances that didn’t allow him to fulfill his dream of returning to the mountain in Puerto Rico, buying a piece of land where he could build himself a casita, and raise chickens and grow coffee. My father worked so hard for so little money, and ultimately, he was rewarded with unemployment, poor health, no health insurance, and an early death. In the United States, he was discriminated against because he was too brown, uneducated, spoke broken English, and because he was Puerto Rican. Papi never had a real chance to fulfill his dream, and it was fundamentally because of the policies of the U.S. government.

“Papi worked on the assembly line in Chicago factories most of his adult life, and when he died in his early 50s, my brother and I attributed it to the noxious fumes from his work as a welder. One of the reasons I write is that I’ve always felt the injustice of the circumstances that didn’t allow him to fulfill his dream of returning to the mountain in Puerto Rico, buying a piece of land where he could build himself a casita, and raise chickens and grow coffee. My father worked so hard for so little money, and ultimately, he was rewarded with unemployment, poor health, no health insurance, and an early death.”

Many people, including Americans in the United States, don’t even know where Puerto Rico is on the map, or even if the people are U.S. citizens (they are), or understand why at least a million Puerto Ricans aren’t bowing down in gratitude to the United States for designating Puerto Rico a colony and bestowing upon it second-class citizenship and taxation without representation.

Puerto Rico is very important in the grand scheme of things because it is the laboratory where the United States first tries out plans that they want to implement in other parts of the world. From the U.S. military’s decades-long daily bombing of the people-occupied island of Vieques, to population control on Puerto Rican women in the form of sterilization (one-third of Puerto Rican women were sterilized by 1980), to testing Agent Orange, the list goes on. We should be paying attention to Puerto Rico right now.

7. After the great San Ciriaco hurricane devastates the island of Puerto Rico in 1899, your protagonists Vicente Vega and Valentina Sanchez are lured to Hawaii, another U.S. territory, on false promises of prosperity by way of the sugar trade. What was something especially striking that you learned about the United States’ colonial projects when juxtaposing these territories in your writing? How did the act of writing aid you in engaging with history?

What surprised me the most in my research is that Puerto Ricans are faced with a similar situation today as in 1900—they have no say in their own country, there are no jobs, economic conditions are dire, and land is being bought up by Americans and American corporations and Puerto Ricans are being pushed out.

I didn’t intentionally juxtapose the two territories—that was the work of the United States when it invaded Puerto Rico and overthrew the Hawaiian government and claimed the islands for themselves. I took the historical facts of the 1898 U.S. military occupation of Puerto Rico and the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane, how these two devastating calamities cumulated with American businessmen giving Puerto Ricans a good shove off their own island.

“I have always loved history, and once I claimed for myself that I was a writer, I claimed Puerto Ricans and Puerto Rican history as my subject. But it wasn’t because I knew so much Puerto Rican history—it was because I didn’t know much. My parents didn’t know much either because that’s what happens when you are a colony: your history is erased. Now I’m learning about my ancestors and my ancestral homeland, and through writing, I am able to imagine their stories, my ancestors’ stories, Puerto Ricans’ stories. I’m blessed.”

The American sugar planters had a special interest in recruiting Puerto Ricans for the Hawaiian sugar plantations because they wanted to “whiten” the race of their cane workers. They wanted to bring in another nationality to weaken the organizing of the Japanese workers who had been there for years and were beginning to protest the difficult conditions and ill-treatment. The disdain and prejudice of the U.S. government toward both the people of Hawaii and the people of Puerto Rico is blatantly clear in newspaper articles and editorials of the late 19th and 20th centuries, certainly, in Hawaiian and Puerto Rican newspapers.

I was telling someone the other day that I have only just understood that I have been in training to write historical fiction from a very young age, beginning with my mother’s stories about growing up poor on the mountain in 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s Puerto Rico. I have always loved history, and once I claimed for myself that I was a writer, I claimed Puerto Ricans and Puerto Rican history as my subject. But it wasn’t because I knew so much Puerto Rican history—it was because I didn’t know much. My parents didn’t know much either because that’s what happens when you are a colony: your history is erased. Now I’m learning about my ancestors and my ancestral homeland, and through writing, I am able to imagine their stories, my ancestors’ stories, Puerto Ricans’ stories. I’m blessed.

8. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

From early childhood, I felt a connection with Puerto Rican music. My father would play música típica or jíbaro records, and my parents and the aunts and uncles and even us little kids would dance to it at family parties. Later, it was salsa. My favorite songs weren’t love ballads or boleros—I connected with songs about yearning or nostalgia for a past, or about promises made and not kept, or down-on-their-luck people, like Héctor Lavoe’s “El Día de mi Suerte,” where he sings about how he’s still waiting for his lucky day.

When I first began work on The Taste of Sugar, I listened to songs about the political repression of Puerto Rico by the United States. One favorite was a song in the bomba genre—Black Puerto Rican music—that snuck through the United States’ censorship because the Americans didn’t understand the Spanish lyrics about the United States bombing the island. Right now, I am compiling a fantastic soundtrack that is inspiring the work on my new novel The Girls from Humboldt Park.

“After 123 years of U.S. colonialism, Puerto Rico deserves a serious self-determination process, and only Puerto Ricans should decide the future of Puerto Rico. The Taste of Sugar narrates the early days of the U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico and its subsequent colonization, and how being a colony was detrimental to the Puerto Rican people. Not much has changed, and I hope that The Taste of Sugar can help people to understand why only Puerto Ricans must decide on the political status of Puerto Rico.”

9. Which writer, living, or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I think it would be Anton Chekhov. He had such a profound understanding of human beings. The first time that I read Peasants, I connected to that story in such a profound way that I felt my heart a little broken. I like a little heartbreak in fiction. In that story about Russian peasants, I saw my people: Puerto Rican jíbaros like my ancestors, migrants like my parents.

Chekhov was a 19th-century Russian in a continent on the other side of the world writing about Russians, but he could have been writing about Puerto Ricans. I’d like to discuss serfs and jíbaros with Chekhov. I bet he would be very interested to learn about the travails of the Puerto Rican people, past and present.

10. What did it mean for you to publish a novel during such a tumultuous time? What changes to your publication plan did you have to make in the midst of a pandemic?

Liveright, my publisher, was concerned about the publication of The Taste of Sugar bumping against the 2020 presidential election, so I worked on edits while on vacation with my sisters in Italy, so that the manuscript would be ready for a June 2020 publication. Then the pandemic hit, but Liveright decided to go ahead with publication. It was a blow not to be able to have in-person events and to meet my readers, but we’ve done the best we can with virtual events and social media. I’m grateful for the great reviews.

On another level, the publication of The Taste of Sugar couldn’t have come at a better time for Puerto Ricans on the island or in the diaspora. The Puerto Rico Self-Determination Act H.R.2070 (PRSDA) is waiting to be voted on in Congress. After 123 years of U.S. colonialism, Puerto Rico deserves a serious self-determination process, and only Puerto Ricans should decide the future of Puerto Rico. The Taste of Sugar narrates the early days of the U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico and its subsequent colonization, and how being a colony was detrimental to the Puerto Rican people. Not much has changed, and I hope that The Taste of Sugar can help people to understand why only Puerto Ricans must decide on the political status of Puerto Rico and maybe even write their representatives in support of PRSDA. That would be very gratifying.

Marisel Vera is a Chicago writer and proud Boricua who grew up in Humboldt Park. Through her work, Vera explores the particular burdens that Puerto Ricans, on the island and in the diaspora, carry as colonial subjects of the United States. Her latest novel, The Taste of Sugar (Liveright, June 2020), was recognized as one of 12 best Latino books of 2020 by NBC News and named the Chicago Reader’s 2020 Best New Novel by a Chicagoan. Set in Puerto Rico on the eve of the Spanish-American War, The Taste of Sugar follows a coffee growing family through the disastrous upheaval caused by the historic events of the 1898 U.S. invasion and the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane. Vera is also the author of If I Bring You Roses (Grand Central Publishing), a story about a couple who leaves Puerto Rico during the 1950s’ Operation Bootstrap seeking the promised American dream in Chicago’s factories. Vera is currently at work on a novel about four Puerto Rican girls growing up in 1970s Chicago, The Girls from Humboldt Park.