The PEN Ten: An Interview with Morgan Parker

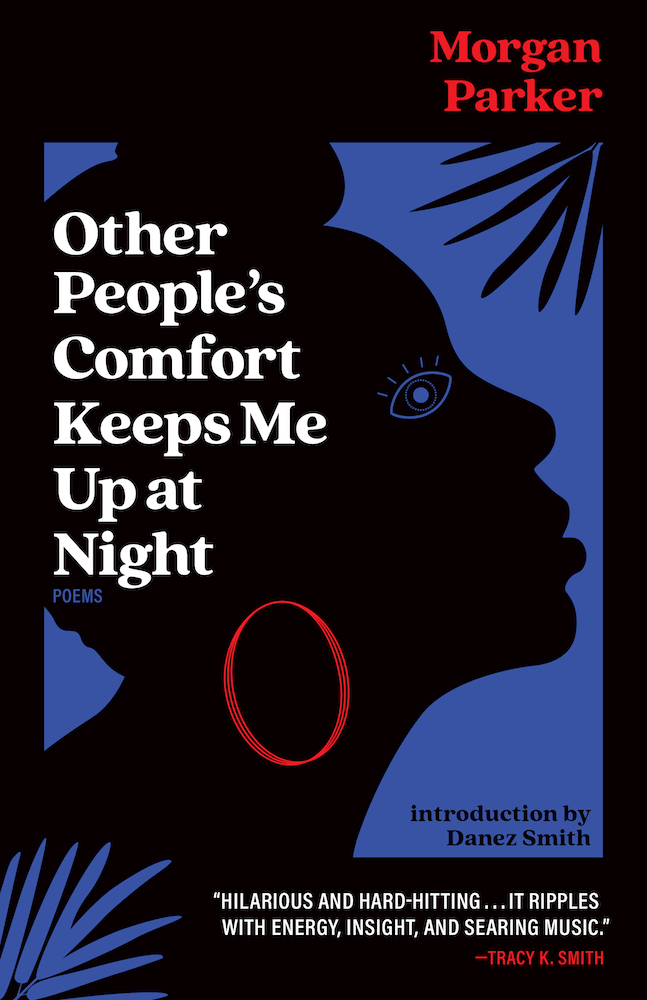

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Morgan Parker, author of Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night (Tin House, 2021).

Photo by Rachel Eliza Griffiths

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

The Bluest Eye. I say that’s the book that radicalized me, not only because structurally and lyrically it’s a beautifully strange book, but also because it whispered that my private insecurities were normal. Specifically, I point to the passages about white dolls and Shirley Temple, the resentment of beauty standards. I read it too early to take in all the themes, but that one spoke to me immediately.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? How might poetry as a literary form be uniquely equipped to grapple with obscured truths?

A few years ago, I said in an interview “facts are white,” and that’s how I tend to approach truth in my work: as a figment, a construction. A lot of that is because it relies on the stringency of linear time, chasing a neatness that just isn’t real life. Poetry disregards much of this narrative restriction and allows multiple perspectives in a single line, even. Stretches our concept of the sentence and our sense, often, of stability and certainty and pushes us to think and see differently, even just to acknowledge that those differences exist.

“I tend to approach truth in my work as a figment, a construction. A lot of that is because it relies on the stringency of linear time, chasing a neatness that just isn’t real life. Poetry disregards much of this narrative restriction and allows multiple perspectives in a single line, even. Stretches our concept of the sentence and our sense, often, of stability and certainty and pushes us to think and see differently, even just to acknowledge that those differences exist.”

3. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

I think it’s that pesky “truth” problem. If we can’t agree, globally and nationally, on some basic realities of the past and present—such as mass genocides and death tolls—then expression is useless. If we’re all too stubborn to hear each other, why are we talking?

4. How does your identity shape your writing?

It’s where I’m coming from. Not just the way I see, but how and why I see it that way, and how that context can challenge or inform readers’ perspectives.

5. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

First of all, I hope you know how impossible of a question this is. And second of all, I am excluding James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, as I believe these choices are a given. Like, duh. Excluding them, I’d say June Jordan, because I’m obsessed with her brain, and I could talk to her about anything from architecture to academia to global politics.

6. Throughout the collection, you don’t shy away from giving credit to artists and writers who have influenced you. The voices of Jay-Z and Frank O’Hara interweave with yours and are palpable in the diction, rhythms, and musicality of your poetry. In your author’s note, you also thank Biggie Smalls, Curtis Mayfield, and Roy Lichtenstein, among others. Why is it important to you to acknowledge the individuals that inspire you? Why should your readers know that they shaped you?

6. Throughout the collection, you don’t shy away from giving credit to artists and writers who have influenced you. The voices of Jay-Z and Frank O’Hara interweave with yours and are palpable in the diction, rhythms, and musicality of your poetry. In your author’s note, you also thank Biggie Smalls, Curtis Mayfield, and Roy Lichtenstein, among others. Why is it important to you to acknowledge the individuals that inspire you? Why should your readers know that they shaped you?

This was a very early-twenties first-book move, when I was only just beginning to consider the reality of publishing my work for public audiences; and also, just beginning to consider the power and possibility in my voice. It’s become a touchstone of my work since, but at the time, approaching my poems as collages of references and daily experiences was new terrain.

I didn’t have a concept of how to credit each influence—in the already-long list you mention above, I can think of a handful of references left out, and poets have differing views on these things. To thoroughly annotate any book of my poems—including phrases, stolen titles, fragments of lyrics—I’d probably need 10 pages. Sometimes, the references, like a mixtape or chopped/screwed track, float in unconsciously. I think of Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night as a big house party, packed with personalities and voices, and listing many of those individuals and sources was my way of calling them all up.

7. What do you read (or not read) when writing poems?

I don’t always read poetry while I’m writing poems, unless it’s intentional, because I don’t want to adopt anyone else’s rhythm. I like to read theory and nonfiction and bring those ideas to poetry. Fiction’s not the same. Reading poetry while writing in any other genre is always helpful.

“I’ve missed audiences more than anything. Writers know it’s a lonely art, until it’s not, and you’re in a room sharing it with folks. I write for that connection, and I’ve missed connecting with readers in real life.”

8. What advice do you have for young writers?

Do whatever you want. That may sound glib, but I mean it: especially for poets, working in a genre with traditional formal constraints, it’s important to remember you’re making art. There’s no poetry police. You’re not doing it wrong. Make room to play around, experiment, weird yourself out. Also, read widely!

9. You co-curate the reading series Poets with Attitude (PWA) with Tommy Pico. Why do you think it’s important for writers to create a community with other writers? How have you done this (or what have you missed about this) in the last year and change, which has been devoid of live literary events?

I’ve missed audiences more than anything. Writers know it’s a lonely art, until it’s not, and you’re in a room sharing it with folks. I write for that connection, and I’ve missed connecting with readers in real life. Tommy and I notoriously love performing, and PWA started because we both consider it a vital part of our poetry. We’re Sags and very social, so building that comradery with other writers is energizing.

10. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

Frank O’Hara is an obvious one, especially in my first book. Other ancestors on my white writer side are Allen Ginsberg and Anne Sexton—both of them were early influences. On my Black side, June Jordan, Zora Neale Hurston, Amiri Baraka, and Langston Hughes.

Morgan Parker is a poet, essayist, and novelist. She is the author of the young adult novel Who Put This Song On? and the poetry collections Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night, which has just been reissued by Tin House, as well as There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé and Magical Negro, which won the 2019 National Book Critics Circle Award. Parker’s debut book of nonfiction is forthcoming from One World. She is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, winner of a Pushcart Prize, and has been hailed by The New York Times as “a dynamic craftsperson” of “considerable consequence to American poetry.”