The PEN Ten: An Interview with Franny Choi

Photo credit: Francesca B. Marie

Franny Choi doesn’t see dystopia as science fiction.

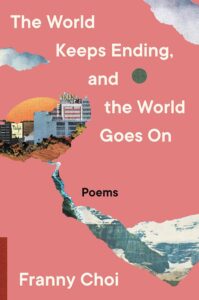

In her poetry collection The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On (HarperCollins, 2022), Choi writes about the dystopias that are happening now, and historically, to marginalized people everywhere.

In conversation with Community Outreach Manager Alejandro Heredia for this week’s PEN Ten, Choi explains why traditional ideas of dystopia can be dangerous. (Amazon, Bookshop)

1. I want to start by talking about dystopias. We tend to think of dystopias as imagined places in the near or far off future. But this poetry collection highlights the many ways our current world feels like a dystopia. Do you find dystopian literature useful to help us understand our (collective) lives? Do you find the genre limiting? Where do you think the collection fits in contrast, relationship to, or alongside dystopian literature?

Dystopian literature doesn’t come out of nowhere; I believe it’s a genre we inherit from the realities of racial capitalism. If I were being a little ungenerous, I would say dystopian literature has historically been a literature that uses the stories of subjugated people as the basis of a horror story for the privileged: What if everyone (not just people from the Global South) had to migrate to survive? What if no one (not even middle class white women) had reproductive autonomy? At best, dystopian literature helps us process the unfathomable realities of the present and imagine other ways of being. At worst, I think it can become a kind of cathartic fantasy that actually ends up making the lived realities of oppressed people less visible, by calling them sci-fi. I think this is partly why I decided not to envision extravagantly terrible futures in this book—the word “dystopia” really only appears in the present and the past.

2. Any favorite dystopian books, movies, or art pieces that got you thinking as you were crafting these poems?

Yes, many! Severance, by Ling Ma, Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam, and Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich: I think I read those three back-to-back. Related to the previous question, I thought a lot about the distance between the novel and the TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale. Brenda Shaughnessy’s The Octopus Museum, Traci Brimhall’s Our Lady of the Ruins, and Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s M Archive taught me a lot about the genre of speculative poetry. And then of course the works of writers like Paul Celan and Don Mee Choi helped me think about the poetics of lived and historical dystopias.

“For me, and for this book, hope is the willingness to imagine beyond this world—to travel, as a poet, into the parts of the poem that are unknown to me and to try to make something there, in thorny questions of solidarity, in the limits of healing, amid uncomfortable paths of history, in the worlds I couldn’t quite imagine.”

3. A lot of these poems refuse to give the reader an easy out, a balm, a reassertion of order. I’m thinking of “Celebrate Good Times,” for example, where you write, “No, thank you, / I’m stuffed, I couldn’t possibly have more hope. I haven’t finished / mourning the last tyrant yet.” Can you speak a little to your exploration of hope in these poems, and what inspired it?

Many of the early poems in this book emerged in the aftermath of 2016, which was, at least for me, a period of time when hope didn’t come easy; it was something everyone around me was fighting hard to cultivate. It’s a vulnerable position to put yourself in: to believe in something better, despite all the signs that you’ll be disappointed. I found Rebecca Solnit’s book Hope in the Dark instructive in those years. She draws on the writing of Ernst Bloch, among others, to define hope not as the simple faith that everything will be okay, but as the willingness to believe that the future is truly unknown. For me, and for this book, hope is the willingness to imagine beyond this world—to travel, as a poet, into the parts of the poem that are unknown to me and to try to make something there, in thorny questions of solidarity, in the limits of healing, amid uncomfortable paths of history, in the worlds I couldn’t quite imagine. It was a craft challenge for me, to write two steps beyond what I know, and I’m sure that the experiment didn’t always work, but I learned a lot in the process.

4. What is your writing practice like? Did it change at all as you were writing the poems in this new collection?

My practice varies somewhat depending on the project, but it almost always involves drafting at night and revising in the morning. For this book, the combination of a defined (if huge!) set of themes and the challenge to write into the unknown meant that I produced a lot of exploratory drafts: trying stuff out, working a question over and over, following an idea in five or six different directions. And because this book is a little more musical than my last, “revising” usually meant redrafting from the top rather than tinkering at the lines, as a way of trying to preserve rhythm and stay improvisational. Finding the poem was often more like a process of doing multiple takes of a performance, rather than sculpting it out of one piece of rock, if that makes any sense.

5. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process, and how did you overcome it?

One of the most instructive challenges of making this book was a series of conversations I had with my mother about a poem that depicted an experience she’d had with the police when I was a kid. She was very resistant to my publishing it—and not just resistant, I realized, but afraid. It forced me, first, to confront that I hadn’t understood exactly how deeply this memory had impacted her, and second, to question what I was doing by turning her into a sort of character in my book. And it brought home to me a lesson about the deep wounds of shame that state violence enacts; that some of the greatest harm it inflicts is in the way it shapes our sense of ourselves. Ultimately, even though I was sure that the book’s arguments about policing wouldn’t exactly make sense without this personal story, it became clear that my responsibility to my mother’s humanity outweighed my obligations to my argument. I wrote a poem in place of that poem (which I called “Poem in Place of a Poem” because I’m annoying), which I hope serves as a kind of monument to that silence.

“Finding the poem was often more like a process of doing multiple takes of a performance, rather than sculpting it out of one piece of rock, if that makes any sense.”

6. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

When I was a kid, one of my favorite picture books we had at home was about the Korean independence movement activist Yu Gwan-Sun, who died in 1920, at just eighteen years old, after being tortured in a Japanese prison. (You know, a fun story for kids.) I remember getting to the part of the story where she shouts “Manse!” (the rallying cry of the independence movement, meaning something like “Long Live Korea”) over and over in her prison cell, despite being repeatedly punished by the guards. It stuck with me as a young kid, how futile it was to repeat this chant, and also how the power of the chant had lasted beyond its futility, beyond Yu Gwan-Sun’s death.

7. If you could claim any writer(s) from the past as part of your own literary tradition, who would you claim?

Octavia Butler, Paul Celan, June Jordan, Grace Lee Boggs, Gwendolyn Brooks, Anna Akhmatova, Bei Dao, Lucille Clifton, Aimé Cesaire, Theresa Hak-Kyung Cha. I don’t know if I can claim them, but I’ll keep reaching toward them, and hopefully find others to reach toward.

8. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

So many! I think I did sort of a bad job keeping up with new poetry this year, but Courtney Faye Taylor and Kemi Alabi’s books blew me away. I’m currently reading Tawanda Mulalu’s fantastic debut, Please Make Me Pretty, I Don’t Want to Die. At Massachusetts Review, we published an incredible poem/performance piece by my dear pal Alison Rollins called “A Bell is a Messenger of Time.” A poem by Hari Alluri recently made me, very literally, throw my hands up and shout—what a gift. And of course, I have to say that I am very, very excited about the new hosts of VS (Ajanaé Dawkins and Brittany Rogers) and all the writers who were at last year’s Witches & Warriors Retreat.

“It is in power’s interest to keep people isolated, and community and chosen family are one of the only reliable antidotes I’ve ever encountered to the myth that we don’t (or needn’t) rely on each other.”

9. Friendship is everywhere in this book, even when it isn’t directly the subject. Why is friendship so important, at the end of the world?

Oh, the simple answer is that I love my friends; they’ve been with me through the growing pains, taught me how to make a life in art, seen me when I couldn’t see myself, gotten me through every minor and major catastrophe of my life. Another way to say this is to say that it is in power’s interest to keep people isolated, and community and chosen family are one of the only reliable antidotes I’ve ever encountered to the myth that we don’t (or needn’t) rely on each other. There was that brief window of 2020, when it seemed like we all might finally have learned that; I think holding onto friendship is one of my ways of trying to keep cracked the window that, when fully open, might look something more like mutual aid, collective organizing, a healthy ecosystem of the grassroots.

10. One of my favorite lines in the collection comes at the end, in the poem “Doom.” You write, “we knew the end was coming here. We knew it, / and like idiots – like perfect idiots – we stayed.” I laughed a little here. Because we have such a large capacity to hold on to faith even in the face of total annihilation. The ending of the collections feels, dare I say, hopeful. Not in changing the catastrophic circumstances around us, per se, but the poems felt to me like a meditation on a deep faith in humanity, despite what “idiots” we can be. Is that what these ending poems feel like to you? Do you continue to have faith in us, despite it all?

I’m writing this the morning after the Lunar New Year, the morning after the shooting in Monterrey Park, in a year after a year after a century of grief. I think it depends on who that “us” is. I don’t have faith in “us,” but I do have faith in us, you know?

Franny Choi is the author of three books: The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On (Ecco, 2022), Soft Science (Alice James Books, 2019, winner of the Elgin Award) and Floating, Brilliant, Gone (Write Bloody, 2014). She is a Lilly/Rosenberg Fellow, a recipient of Princeton’s Holmes National Poetry Prize, and a graduate of the University of Michigan’s Helen Zell Writers Program. Franny is Faculty in Literature at Bennington College and founded Brew & Forge, a project that builds connections between writers, artists, and movement organizers. They live in Western Massachusetts.