The PEN Ten: An Interview with Saket Soni

Organizer and writer Saket Soni tells the unbelievable true story of 500 foreign workers lured to the United States from India and trapped into forced labor. A gifted storyteller, he blends his own training as a playwright with inspiration from adventurous thrillers to capture the harrowing journey of people like himself, who are divided between worlds.

“Writers and exiles are so fundamentally alike. There’s nothing like writing to make you realize you’re more than one thing, and belong to more than one place,” he told former Senior Producer Nancy Vitale for this week’s PEN Ten.

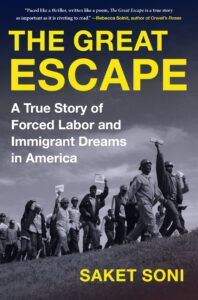

The Great Escape: A True Story of Forced Labor and Immigrant Dreams in America (Workman Publishing, 2023) is the astonishing story of how the laborers were lured here – told by the visionary labor leader who engineered their escape and set them on a path to citizenship. (Amazon, Bookshop)

1. Many of our readers will be surprised to know that, despite your crucial work as an organizer of trafficked migrants, you started your career as a playwright. Can you share a bit about your creative process in writing creative nonfiction?

I knew I had a story on my hands that could move like a propulsive thriller—and be populated by complex and compelling characters—if I could do it justice. The tricky part was rescuing immigrants from an “immigration story,” and recasting them as the protagonists in a nonfiction thriller. To do that, I leaned on a whole host of dramatic models. I borrowed elements of story engines from detective novels, heist films, great TV… anything that would help me live up to the electricity of the story.

2. Given the breadth, time scale, and geography of this story, how did you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Remain inspired—during the writing of the book? Much of the raw material for the book I gathered through hundreds of hours of interviews with the Indian men who lived through it with me. We revisited some of the hardest moments in our lives in these conversations—but always over extraordinary meals. There are many wonderful food moments in the book, and there were many more between us in the writing. If you’re looking for inspiration, just try Bincy’s fish curry (recipe on page 305).

“Writers and exiles are so fundamentally alike. There’s nothing like writing to make you realize you’re more than one thing, and belong to more than one place.”

3. You were born in India, and have lived in the United States for some time. You’re an artist, an organizer, a strategist, and more. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Writers and exiles are so fundamentally alike. There’s nothing like writing to make you realize you’re more than one thing, and belong to more than one place. I’m an immigrant, but I’m undeniably American. I’m an American, but I’m undeniably from Delhi. When I’m with my artist friends, I’m their organizer friend sitting in. Among organizers, I’m considered the storyteller. As the son of a diplomat, I grew up between worlds, and in many ways, having more than one identity became my identity–that’s part of what’s dramatized in the book. We all have complicated identities, and we all feel like we’re looking for home.

4. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I grew up in India in my grandmother’s house, in the densest part of Delhi. In that crowded house was a crockery cupboard that held all my dad’s college books. One summer when I was around 12 years old, he inducted me into that cupboard. It became an annual tradition: he would open the sliding glass doors and we’d reach deep into the disorganized piles together, never knowing what we’d get. Out came Hemingway and Freud, the book for the musical Hair, Günter Grass, Pearl S. Buck, George Orwell… all in yellowed paperbacks that smelled of dust and vanilla.

The book that came out the first time, one that really seared a hole in me, was Albert Camus’ The Stranger. All the din and dizziness of Delhi in the summer fell away, and I disappeared into the world of the book. Then, in the evenings, my father and I would talk about what I’d read. He was a man of few words, but these books would spark memories for him, and his stories would come out: where he was in life when he read them, why they were important to him. The books were a transport for me and a bridge between the two of us.

5. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

There’s a crowd I reread continually: Rumi, The Arabian Nights, G.V. Desani, Salman Rushdie among them. In my college years I had the impossible good fortune of both reading and taking classes with Toni Morrison, J.M. Coetzee, and Wendy Doniger. They remain three of my most important writing teachers.

“By temperament and training as a labor organizer, I initially wanted to keep myself out of the book. But it didn’t come alive until I did—until I dug into my own search for home, and mined the deep parallels between the men’s journeys and my own.”

6. And moving on to writers working today, which are you most excited by and why?

Among the writers who gave me the courage to write The Great Escape, there’s Patrick Radden Keefe, who writes about real-world evil like no one else; Suketu Mehta, for his writing about his own homecoming; and Katherine Boo, who writes the most propulsive non-fiction possible about the least visible people in the world. Rebecca Solnit’s writing is tonic for our times. And I’m always learning from Ayad Akhtar, Jenny Offill, Emily St. John Mandel, and Diane Seuss.

7. What’s a piece of art that moves you and mobilizes your work?

Right now, Pakistani singer Arooj Aftab’s “Mohabbat,” a contemporary take on an old Urdu ghazal. Astonishing.

8. I often felt while reading the book that I was right there with you and the men on the journey. Were you ever surprised by what you were writing, or in the process of writing the book? In what way?

By temperament and training as a labor organizer, I initially wanted to keep myself out of the book. But it didn’t come alive until I did—until I dug into my own search for home, and mined the deep parallels between the men’s journeys and my own. When the book opens, I’m in the wilderness years of my mid-20s: I don’t call home to India, I don’t relate to it, I think of myself as an American in all but passport. The last person in the world I expect to meet in the Mississippi Gulf Coast is the man whose mysterious midnight phone call launches the story. In India, he could have been my uncle. And here he is in Mississippi, trapped in a forced labor scheme that has him rebuilding oil rigs after Hurricane Katrina. In coming to his aid, I wind up finding my own way back home—into a deeper relationship with my parents, my language, and the places I’m from..

“Writing helps us see each other, and changes the way we see the world as a result. Only good long-form writing can hold you in contact with someone else’s interiority, their motivations, their makeup, for hours or days or weeks. In a divided world, we need that passport into each other’s reality. “

9. What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words?

The most unexpected thing has to be my encounter with Alvin Ladner, the ICE agent who hunts and tries to criminalize the workers for much of the book. When I tracked him down during the writing of The Great Escape, the first surprise was that he was willing to meet with me. I showed up ready to fight him, to confront him over all the pain he had caused, and to write him into the book as a villain. As it turns out, it’s hard to spend six hours on a porch with someone—peering into their life, trying to understand from their point of view why they made the most consequential decisions of their life—and not come away with some sense of connection, some empathy. I went there ready to demand understanding from him, but it turned out that I had to be able to give it too. I had to treat him the way I wanted him to treat others. The encounter wound up being not just the climax of a conflict, but the beginning of a friendship I never could have expected. That’s what I ended up writing.

10. What is the role of the writer in an era of social instability and polarization?

Writing helps us see each other, and changes the way we see the world as a result. Only good long-form writing can hold you in contact with someone else’s interiority, their motivations, their makeup, for hours or days or weeks. In a divided world, we need that passport into each other’s reality. If in some small way, The Great Escape transports you into the worlds of its characters—of men with family dramas and love stories and children they’re trapped 10,000 miles away from, of security guards at the barbed-wire gates who have more in common with the men they watch than with their employers, of ICE agents struggling to hold onto a measure of self-respect even while they hunt the men across half the country—if the book can be your passport into their reality, then I’ve done my job.

Saket Soni’s writings have appeared in the L.A. Times, in the Nation, and other publications. And he is an experienced speaker nationally. Past engagements have included major foundation boards, the United Nations, the Council on Foundations, and progressive gatherings convened by leading organizations such as the Aspen Institute, the Economic Policy Institute, and the Center for American Progress. The Great Escape, published by Algonquin Books, is his first book.

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series.