The PEN Ten: An Interview with Arinze Ifeakandu

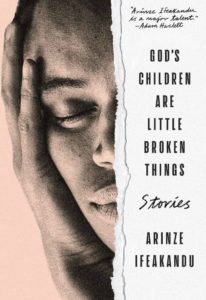

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Literary Programs Coordinator Viviane Eng speaks with Arinze Ifeakandu, author of God’s Children Are Little Broken Things (A Public Space, 2022). Amazon, Bookshop

1. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

The last book I read was Hue and Cry by James Alan McPherson. Currently, I’m reading The Great Mistake by Jonathan Lee, which is truly beautiful so far.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

I take a lot of breaks. I like to remove myself, but also want to be able to be in the midst of people after that removal. I watch people, I stay in my head, I have conversations, listen to music, and when I’m at my desk, I want that excitement to be the driving force.

“I like to remove myself, but also want to be able to be in the midst of people after that removal. I watch people, I stay in my head, I have conversations, listen to music, and when I’m at my desk, I want that excitement to be the driving force.”

3. Your collection God’s Children Are Little Broken Things consists of nine moving stories centered on queer love in contemporary Nigeria—loves that are forbidden, all-consuming, and tender all at once. Why did you feel like it was important to amplify these stories?

I needed, firstly, to read stories that reflected my experience, my… daydreams? When I was a little boy, I would fantasize about being a priest, owning a nice simple house, preaching nice, heartfelt sermons and returning home to my wife and two children. Something simple, I’d say. But it was boys who made my heart go wild. Boys were incredibly beautiful to me, not in the way that girls were—girls were beautiful in factual ways: fine girl. Boys, I wanted to hold. Soon, I began to write stories that satisfied this longing, especially as I began allowing myself freedom to be with, and think of, boys. Representing that love was my way of perhaps participating something my heterosexual peers enjoyed without second thoughts.

4. What is your relationship to place and story? Did writing this collection redefine your connection to your home country?

I think I am very affected by wherever I live, and I have been happiest wherever the streets feel lived-in. Places with schools around the corner and people in the street, and shops, and random encounters. When a place feels stripped down, something in me retreats. In writing these stories, I took for granted the fuel that was my surroundings, especially because I sometimes could not find privacy when I needed it. Not sure the collection directly redefined my connection to Nigeria, but by the time I completed it, it was clear to me how deeply I loved Nigeria, which made my anger and heartbreak at the dysfunction even more incandescent.

5. You were a finalist for the AKO Caine Prize for African writing in 2017. How did it feel to have your writing recognized in this capacity?

It was wonderful, mostly for the experience: I got to travel outside the country for the first time. Editors wanted to talk to me. There were all these events and people wanted to talk about stories. I was like, Wow.

“Not sure the collection directly redefined my connection to Nigeria, but by the time I completed it, it was clear to me how deeply I loved Nigeria, which made my anger and heartbreak at the dysfunction even more incandescent.”

6. In God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, language, denotation, and connotation have a fluid relationship. What characters say take on different meanings when they speak, between Igbo, Hausa, pidgin, and English. What are some things that get lost in translation when we move between languages, and why were you interested in honing in on these details?

Language is an aspect of characterization, I think. We code-switch in order to feel safe or to communicate more effectively or to flex, or intimidate. Like the clothes we wear, our speech reveals, sometimes, our class. I used language in that way to show clearly the—sometimes—shifting dynamics between characters. Igbo, for example, is sometimes used for endearment, but at other times, it alienates, rebukes. Everything depends on context.

Language is an aspect of characterization, I think. We code-switch in order to feel safe or to communicate more effectively or to flex, or intimidate. Like the clothes we wear, our speech reveals, sometimes, our class. I used language in that way to show clearly the—sometimes—shifting dynamics between characters. Igbo, for example, is sometimes used for endearment, but at other times, it alienates, rebukes. Everything depends on context.

7. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

I’d say, first, the threat of bodily violence. And then the threat of social stigmatization and verbal attacks. There’s a new kind of born-again self-righteousness gaining ground, complete with the hypocrisies, easy judgments, ostracization—the same religious zeal though without the baggage of religion, with all its power and history. And because that baggage isn’t (visibly) there, it is easy to not see this for what it is: some sort of simple-minded fundamentalism. But I feel most threatened by the first kind, though nothing has directly threatened me.

8. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

This changes from time to time, and it is almost always a song.

“Language is an aspect of characterization, I think. We code-switch in order to feel safe or to communicate more effectively or to flex, or intimidate.”

9. What is one critique of your work that you have really learned from?

I’m not going to share the first one that comes to mind because I’ve shared it a lot—humans are complicated, it was—but Charles D’Ambrosio said to me once in workshop that sometimes when we describe places we know, we often forget that readers do not know those places as intimately, and so we often fall under the trap of undershowing, for want of a better word. That was helpful in that moment because I’d held myself back, thinking I had captured too much of the physical—a useless anxiety—whereas I hadn’t even begun to show what was, and where.

10. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be? What would you want to discuss with them?

Chinua Achebe, Buchi Emecheta, James Baldwin, Binyavanga Wainaina. I would like to have a chill evening with them, talking about life experiences. Mostly listening, to be honest, to whatever stories the evening leads them to.

Arinze Ifeakandu was born in Kano, Nigeria, and currently lives in Tallahassee, Florida. An AKO Caine Prize for African Writing finalist and A Public Space Writing Fellow, he is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. His work has appeared in A Public Space, Guernica, the Kenyon Review, One Story, and Redemption Song and Other Stories: The Caine Prize for African Writing 2018. God’s Children Are Little Broken Things is his first book.