PEN America features a series of short stories by Ukrainian writer and filmmaker Oleg Sentsov who was sentenced to 20 years in a Siberian prison in August 2015 on trumped up charges of terrorism after being a vocal opponent of the Russian annexation of Crimea. He has been on hunger strike for a second month now to urge the Russian authorities to release all Ukrainians unfairly imprisoned in Russia. PEN America is calling for his immediate release.

PEN America features a series of short stories by Ukrainian writer and filmmaker Oleg Sentsov who was sentenced to 20 years in a Siberian prison in August 2015 on trumped up charges of terrorism after being a vocal opponent of the Russian annexation of Crimea. He has been on hunger strike for a second month now to urge the Russian authorities to release all Ukrainians unfairly imprisoned in Russia. PEN America is calling for his immediate release.

“Testament”

We are all going to die. And I, unfortunately, am no exception. We’d all like to live a bit longer, and here I, fortunately, am also no exception. No, I don’t want to extend my life in order to live to a hundred and spend the last quarter of it dragging out my decrepit existence on various machines and drugs. I want to live my young, full life a bit longer, to receive pleasure from life and to give pleasure to others, to walk, or even better to run, to sleep at night or not sleep, and I want to be the one who decides all of this, not my organism and my doctors.

This is the kind of life I’d like to live for a bit longer. But it’s not possible. We are all going to die. After death, we will all turn into lumps of rotting meat, buried a couple of metres underground. The worms will eat us, and our dutiful relatives will visit our graves, wear sad expressions on their faces, stand in front of the cross or gravestone, look at our portraits, forgetting entirely that crosses are planted at the feet of the departed, so the whole mournful company is now standing on his head and gazing tenderly at the portrait etched into the granite. Then they’ll get their supplies and booze out, and make sure everyone has a drink, including the deceased, of whom there won’t be much left by that time, and the flowers will bloom all around. Pathos and superstition, pointless religious-pagan rituals and scholasticism.

I don’t want people trampling on my head, even after I’m dead, and I don’t want my children and grandchildren to remember me as a portrait on a slab of granite. I don’t want a wake on my grave. I generally don’t like drawing attention to myself, not now, and certainly not after I’m dead. I don’t want a grave.

When I was a child, just four years old, I went to my grandfather’s funeral. Usually, children don’t remember themselves being that young, and only very occasionally do they remember the most remarkable events from that time. But I remember that funeral. I don’t remember much, but I remember the main thing: me standing at the edge of the grave on a pile of dirt together with my relatives. And then, after the funeral, I was stunned to discover that they wouldn’t be digging grandad up again, that he had died and that was it, forever. Throughout my whole childhood I had a recurring nightmare: In the evening or during the night I would see a black grave and a body in a white shroud being lowered into it. It was grandad’s body, but I imagined that it was me, and I knew that sooner or later it would be. Never take your children to a funeral.

As a child, I was afraid that I would die. Now I’m not afraid—now I know that I’ll die. As I child, I was afraid of the black grave, but now I just don’t want to lie in it.

We are all going to die. Each in our own way. Some will die quietly, as though closing the door to the bedroom of a child who has only just fallen asleep. Others will die in cries and suffering, as though during birth. I don’t know how I will die, but I definitely don’t want to die as a decrepit old man in bed surrounded by yawning relatives.

There was once a man who was asked how he would like to die, and he answered: “With a shout of ‘hurrah!’ on my lips, a gun slung over my shoulder and a mouth full of blood.” I’d also like that—it’s beautiful, it’s manly. But that’s not how it works. Heroes only die beautifully in movies and books. In real life, they piss blood into their pants, scream from pain, and remember their mothers.

I don’t want a grave. I want to be burned. No, not on the bonfire of some inquisition, but in a simple crematorium. Burned, and the ashes sprinkled at sea. If possible, on the Black Sea, and in summer, when the sun is shining and a fresh wind is blowing. But even if it’s autumn and raining, that’s also not so bad. I wouldn’t want you waiting for summer if I kick the bucket in November. Otherwise you’ll have guests round asking, “What have you got in that vase there?” “That’s our grandad, he’s waiting for summer!” The vase should also go into the sea, by the way—no need to fetishize it. Otherwise, that same room, a year later, different guests will ask, “What’s that vase you’ve got there?” “Grandad was in that vase,” the relatives will announce, solemnly getting to their feet. In that case, why don’t we hang my socks and underpants around the house then—my favourite ones, and the ones I wore last?

I want to be burned. To ashes. And the ashes to be spread on the wind. On the sea. Best in summer, if, of course, I die in summer. Just remember to throw the ashes on the wind away from the boat, so that they are blown over the sea and not onto the boat, so that some cheeky grandchild (clearly taking after his grandad) won’t be tempted to comment, as he sweeps up my remains, “Nothing but problems with that old guy!”

Let the wind take my ashes out to sea. But if it’s raining, that’s okay. They’ll all say, “That means we’re burying a good man, since it’s raining.” But you’re not burying—you’re sowing, friends, that is, blowing!

And if it’s raining and the ashes get a bit stuck to the urn, that’s also fine. True, that same cheeky grandchild will look into the urn, see a bit of leftover ashes and say, “Yeah, grandad’s still hanging on!” But that’s fine, just throw the urn into the sea too. So that there’s nothing left. Nothing at all. Just memory. And the things I did. And my friends. And you. And then I’ll always be with you.

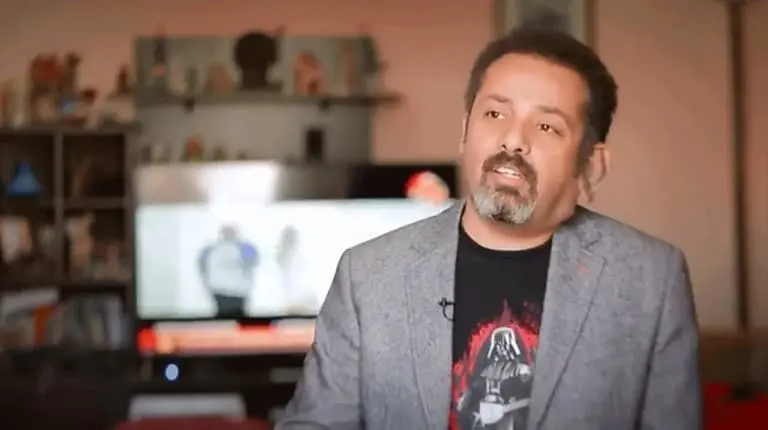

PEN America’s Deputy Director of Free Expression Research and Policy James Tager reads from “Testament” on the 100th day of Oleg Sentsov’s hunger strike.