Temperature Check, Vol. Four feat. Vincent Schiraldi and Edward Ji

A new rapid response series from PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, featuring original creative reportage by incarcerated writers, accompanied by podcast interviews with criminal justice reform experts on the pandemic’s impact in United States’ prisons.

To receive this series straight to your inbox, sign up here.

Volume 4.0 Table of Contents

- Introduction to Temperature Check

- Dispatches from Inside: Prose by Edward Ji

- Podcast: “Fearless Reformer” Vincent Schiraldi

- Featured Work From the PEN America Prison & Justice Community

- Advocacy, Action and Resource Round-Up

Introduction

Checking in on our youth

Dear Readers,

Due to the focus of our programs, our communications typically focus on issues impacting incarcerated adults. But with over 48,000 United States minors confined in facilities away from loved ones—along with the rising stakes around physical safety and the mental health implications of further isolation with COVID-19—we felt it imperative to dedicate a special issue of Temperature Check to our vulnerable youth.

Below you’ll find a Works of Justice podcast interview that draws on the deep expertise of fearless reformer Vincent Schiraldi, who has worked in the juvenile justice space from an exhaustive array of standpoints, both within and outside the system. In a remarkable conversation with our intern Liz Fiore, Vincent offers a depth of insight into the dire circumstances facing youth in detention.

For just a taste of Vincent’s expertise, in a recent USA Today OpEd he wrote:

“While most young people are at lower risk from the virus, youth in the justice system are less healthy than their peers. They have more gaps in Medicaid enrollment and higher rates of asthma, which increases the severity of COVID-19. Locking youth up exacerbates mental illness, dramatically increases the risk of self-harm and is associated with risks lasting into adulthood, including poorer overall general health and increased incidence of suicide.”

And of course, many of our youth are currently incarcerated in adult prisons. The ACLU estimates that each year “250,000 children—some not yet in their teens—are prosecuted in adult criminal courts and subjected to the consequences of adult criminal convictions. In addition, 36 states continue to incarcerate youth under 18 in adult jails and prisons.”

For this week’s Dispatch, rather than a pandemic-specific reportage, writer Edward Ji offers us insight into his experience as a young man sentenced at age 16, and his transition to adult prison on his 17th birthday. It is a chilling and exquisitely written piece of prose that cuts to the heart of the gross failings of our juvenile system.

We invite you to follow the impact of COVID-19 on youth through the Youth Correctional Leaders for Justice website, where Vincent serves as a steering committee member. Read their Coronavirus recommendations for juvenile facilities here.

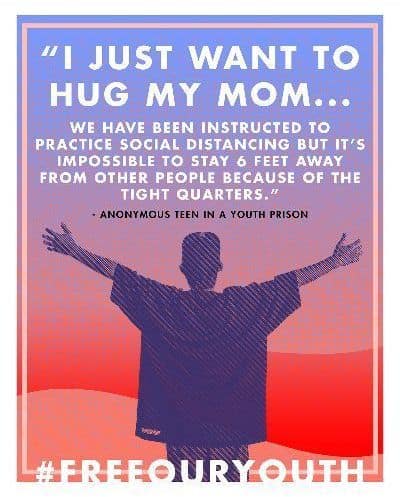

The above poster is from the Performing Statistics/First Youth‘s #FreeOurYouth poster campaign. You can share images, along with other posters and advocacy tools that have been gathered by JustSeeds.

In solidarity,

Caits Meissner

The PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Team

Caits Meissner, Program Director

Robert Pollock, Program Manager

Kate Cammell, Spring 2020 Program Intern

Elizabeth Fiore, Spring 2020 Program Intern

Brookie McIlvaine, Spring 2020 Program Intern

Dispatches from Inside

For Temperature Check, we’re commissioning currently incarcerated writers to share the direct impact of COVID-19 in prison through creative reportage.

Our fourth dispatch, a heartbreaking account of being transferred to adult prison at age 17, comes from Edward Ji (to the left, an image of young Ji shared by his mother), a poet and writer who has received Honorable Mentions in the PEN America Prison Writing Contest for his pieces “The Storm” (2018) and “My Co-Worker” (2019).

After reading the piece below, you might also be interested in checking out this brief and affecting interview conducted with Edward by PEN America Prison Writing Committee Member Eleanor Mammen last fall.

The Number

by Edward Ji

I am prepared to die. My name is Edward Mike Ji, now age seventeen. I am a newly minted adult duly dubbed and declared so by Collin County Juvenile Court, inmate number 207989, and death cannot come swiftly enough. I lay in this foul cell, lay in vegetative rot, a spiritual-mental-physical malaise. The whitewashed walls are a creeping yellow, as if they had absorbed the essence of those who had rotted here before. The stone floor is cracked as if by some titan’s violence, and liable to gnaw at your toenails. The hot fluorescent lights above, seen even through the thin pillowcase wrapped around my head, seem to be intent on slowly cooking me insane.

I wake to the silence of the tomb, blissful and cursed both at once, for the lunatics are still hibernating in bear-like bundles. Whatever hour of the morning it is leaving me alone in this inescapable space with my thoughts and soured memories and dreams, more awake than living and nightmares I can feel. Yes, I am alive. But rather meagerly so. I cannot tell the hour or the day or the month. My lawyer feeds me a letter every few months or so, and I am shocked by the date on the creamy letterhead, at how much time has escaped me. Only the seasons can reach me; I experience twenty minutes of weather a day.

Two cages away, the Korean has hung himself with a TV wire. “Pale as a sheet.” It’s a cliché, I know. But I will not lie. They wheeled him by my hobbit hole on a bright orange gurney, jumping up and down on his chest and he was as drained as a ghost without a drop of blood. They have since drilled our TVs out and cemented them back in two feet higher. With shorter wires.

The intercom announces my “hour out,” a square piece of steel screwed flush with the cinder block perforated with holes half of them permanently jammed with toilet paper. Shut up, some ancestor of mine said. For the love of God, shut up.

One hour a day out of my cell. Twenty-three in. 1,380 minutes. 82,800 seconds. Some of my neighbors have stopped coming out, stopped visiting. They want to be left alone while they quietly wear away. My theory is that there are only two types of insanity, forget what the state psyches say: quiet, polite, insane or obnoxious, profanity-shrieking, bodily-fluid-slinging, 3-A.M.-head-banging insane. I’m grateful to the ones who hold it in. I really am.

I consent to come out. The intercom curses my canine bloodline in a redneck cowboy drawl. I stand in the little chicken wire window of my bank vault door and mime obscene gestures. The guard in the glass cube fires back in kind, with the unfair advantage of a 7Up bottle as a prop. That’s Hutch. He’s cool. He and his partner Gil, who occasionally takes me under the camera to demonstrate hold-breaks.

I’m going to prison. My trial is still months or years off, but we all know it without a word wasted on talking about it. I’m one of the quiet ones.

Gil spends five minutes chaining my hands, then my waist, then my ankles, then my hands loop-the-loop to my waist, all the while grousing about child support and the Evil One bleeding him dry. I tell him he ought to be more careful, avoid these situations in the first place, to exercise self-control. We laugh. Then he starts going off about his last jujitsu tournament and waxes poetic while replaying how he roundhoused some Cambodian’s nose in.

Qiu is waiting for me in the “dayroom.” A single table, two square feet, bolted to a pair of stools, the whole thing bolted to the floor. We’re the only two here, not that they could fit any more. First things first: the chessboard already set up, Qiu grinning hungrily over the plastic pawns. I trounce him quickly, and then point to the pen and paper.

“One more,” he begs in Mandarin. “I know what I did wrong this time. One more chance.”

I get up, clanking awkwardly to the writing pad. He hurriedly sets it on the table.

“First, review from yesterday: Gan-ryi is jail or prison—”

“I’m in pri-son,” he says, smiling.

“Yes, good. Mei-guo is America, or the United States.”

Qiu is waiting for two life sentences. For what, I won’t say. He told me he was innocent. I believe him. Let’s just leave it at that.

Qiu is forty-six years old. I did the math for him. He’ll be seventy-six before he surfaces for his first parole. If they run the sentences together. What if they don’t run together, he asked? I said I didn’t know. He smiled at me nervously.

Continue reading “The Number” Moved by what you read? Respond to Edward’s work by writing to Edward Ji #1575341 Ferguson Unit, 12120 Savage Dr. Midway, TX 75852-3654

Works of Justice Podcast Interview: Vincent Schiraldi, Co-Director of Columbia Justice Lab

To learn more about the particular challenges COVID-19 poses for incarcerated youth, our intern Liz Fiore called up one of the strongest leading advocates in the juvenile justice field, Vincent Schiraldi.

With a national reputation as a fearless reformer, Vincent is currently a senior research scientist at Columbia School of Social Work and Co-Director of the Columbia Justice Lab. Previously, Vincent founded the policy think tank, the Justice Policy Institute, served as director of the juvenile corrections in Washington DC, and then as Commissioner of the New York City Department of Probation. Most recently Schiraldi served as Senior Advisor to the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice.

Listen to the half hour-long conversation on our Works of Justice podcast:

Click here to acceess the transcript or listen on Apple Podcasts Spotify Google Play

Featured Work From the PEN America Prison and Justice Community on COVID-19

Our colleagues in Free Expression at PEN America spearheaded an open letter, signed by over 65 other organizations, demanding prison e-book readers drop access fees during COVID-19. Read our call to action here.

Join us on May 1 for the issue launch of REVERB, the mass incarceration-themed issue of CURA: A Literary Magazine of Art and Action. A collaboration between PEN America’s Prison Writing Program and Fordham’s Creative Writing Program, the event features performances by Aaron Samuels, Carlos Andrés Gómez, Justin Hicks, Liza Jessie Peterson, Louise K. Waakaa’igan and Nicole Shawan Junior. Learn more and RSVP here.

Vanessa Santiago departed as the virus began to spread through the prison. The outside world had changed in ways she was unprepared for. Read PEN America Writing For Justice Fellow Justine van der Leun’s new piece, “I Served 22 Years in Prison and Was Just Released Into a Pandemic” on Medium.

Our PEN America Prison Writing Committee worked with City College of New York’s MFA Program to feature the work of incarcerated writers during their May 9th Revised Reading Series. Learn more about the event here.

Advocacy, Action and Resource Round-Up

Follow the impact of COVID-19 on youth through the Youth Correctional Leaders for Justice website, and read their Coronavirus recommendations for juvenile facilities here.

Essie Justice Group needs your help to #freeblackmamas. Right now there’s a mama sitting in a jail cell with two young children waiting to be reunited with her at home. She has been held pretrial for over a year and denied proper medical care for her medical condition. Essie is ready to bail her out, but they need your help. Her bail is $200,000. With our NBO partners, we’ve raised half of what she needs. Donate now to help them reach their goal.

Die Jim Crow Records, a non-profit record label for formerly and currently incarcerated musicians, is seeking to raise $10K towards getting PPE, masks and hand sanitizer, into prisons. Learn more here.

Teaching writing, art, music, film in prison? Please help raise awareness of intellectual property rights and encourage your students to publish/sell their creative works. Download your free IPFI Handbook for Librarians and Educators here and share with others.

View links to our first issue’s week’s ongoing advocacy efforts, including saving the USPS, a handbook that informs incarcerated people about COVID-19, and poems for decarceration here.