What started as a high school book club in South Carolina has become one of the most effective student groups in the country at fighting book bans.

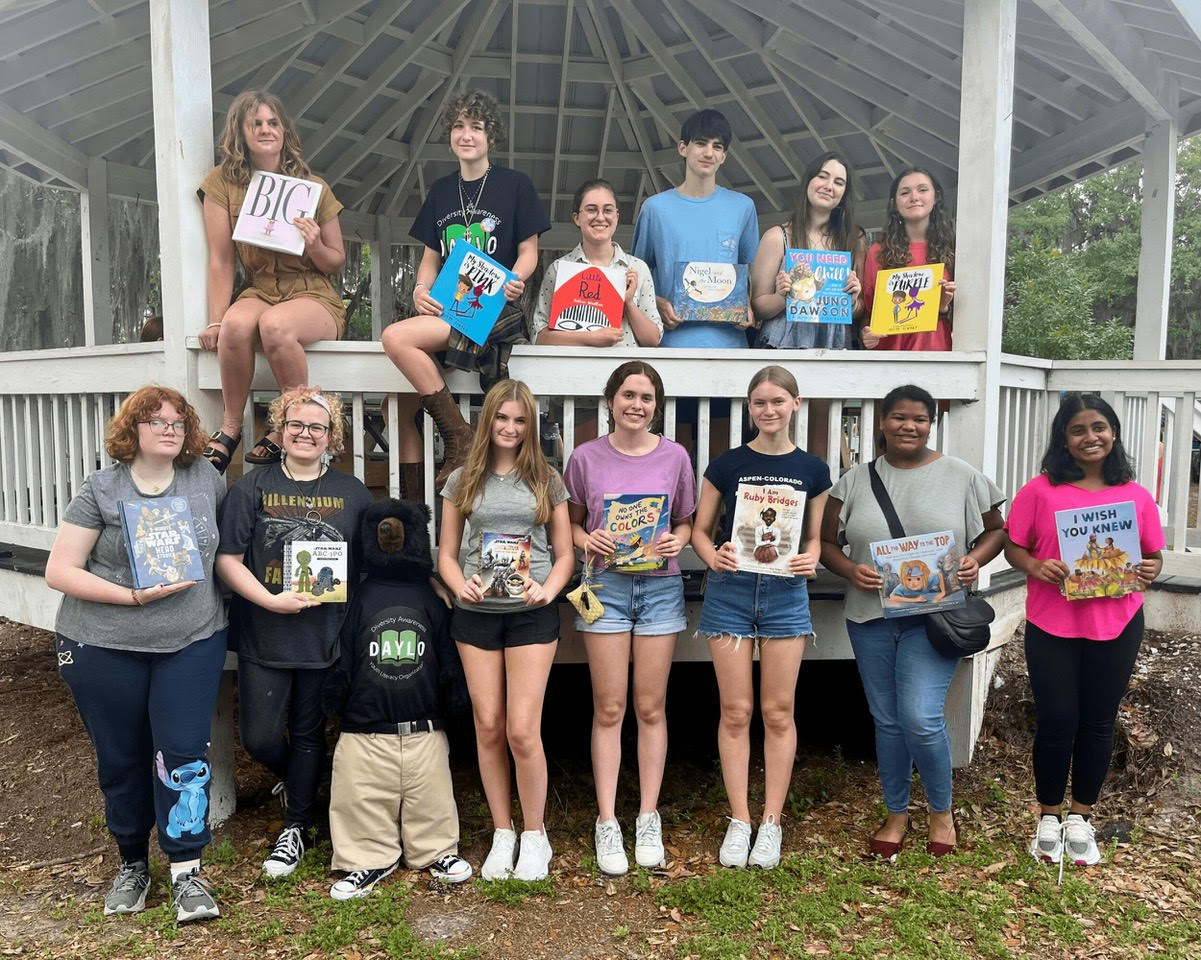

DAYLO (Diversity Awareness Youth Literary Organization) began as a diversity-themed book club in Beaufort that understood reading as an act of advocacy. But when 97 books were challenged in the school district, DAYLO quickly expanded its mission and began the fight shown in the forthcoming documentary Banned Together. Now with 10 chapters across the state, the student group is helping to lead the fight against censorship as South Carolina could become the state with the most statewide bans in the country.

PEN America intern Julia Goldberg spoke with Mary Ruff, Patrick Good, and Dylan Rhyne, three representatives of DAYLO, about their efforts to fight book bans and promote a love of literature. DAYLO is a student-led, mentor-advised organization based in South Carolina. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Mary, Patrick, and Dylan, thank you all so much for speaking with me! I was hoping you could begin by telling me how and when you first discovered DAYLO and what inspired you to join it.

Patrick Good: I first got approached by Lizzie Foster, who was the president of my chapter’s DAYLO before me. I was in speech and debate. I was sitting in a chair on the corner, because it was one of the first practices. It was my freshman year, and there were a bunch of high schoolers in it. And then she just attacked me in the corner and peer pressured me into joining. [Laughs.]

So then I came to the meeting, and I just fell in love with it — with reading books — and then I’d go home and my grandmother would read them with me. I just loved having a safe space to discuss diverse stories.

At the end of the following year, there were rumors about challenges, and then around Thanksgiving, we found out that 97 books were going to be challenged in [Beaufort County]. And then that coming Christmas, we started planning a response.

Dylan Rhyne: I actually heard about it first from our [chapter’s] president. She was doing something in Beaufort related to book banning, where she met [DAYLO mentor] Mr. [Jonathan] Haupt, and he approached her about starting a chapter at [our school]. She mentioned she was doing a thing about books. I said I was interested, and then the next year, we started working on the club.

Mary Ruff: I got involved in the second part of my sophomore year. I heard about school board meetings and how crazy they were, so I went with a lot of my friends to show support, and I just got really into it.

I know that DAYLO was founded in 2019 and has since expanded to include 10 chapters across the state of South Carolina. As the organization has grown, how do you think its mission and the scope of its work have evolved?

DR: I think parts of its initial founding were more centralized on using diverse literature to bring questions into the community. It was [about] fostering discussion. But I think as it’s expanded and as these regulations have moved into South Carolina, we’ve become a lot more politically focused as a whole, although I know many of the organizations, including our own, still run book clubs to keep the heart of it alive. But I do think the chapters have had a lot more focus on advocacy lately.

PG: The way Mr. Haupt often describes it is DAYLO is three parts: It is an advocacy group, it is a community service group, and it is a book club. Originally, it was just a book club and a community service group. And then once the book bans started happening, we added the advocacy side, and now that’s become a major part of DAYLO.

Could you tell me about the projects you’re working on now?

PG: Right now, we’re kind of in an in-between space. In Beaufort County, we had our 97 books that were challenged, of which 91 were returned to shelves, five were banned, and one was never in our school’s libraries — which just shows that these lists are being copied and pasted from somewhere else, that these aren’t original lists. These people haven’t read the books at all. And so after that happened, legislation was passed in the state that these books can now be brought to our state board and then challenged there. [Some of the challenged books retained in Beaufort have been banned by the State Board of Education and more are under review.]

DR: Over the summer, [we kept] a pretty close eye on the bans of AP African American studies in school — technically not book banning, but of a similar realm. At the moment, we’re also working on something — I think it started in Beaufort — the teddy bear picnics. So getting out into the community, and reading to little kids … just getting out there.

What are the biggest obstacles you’re facing as student advocates? How are you working to overcome them?

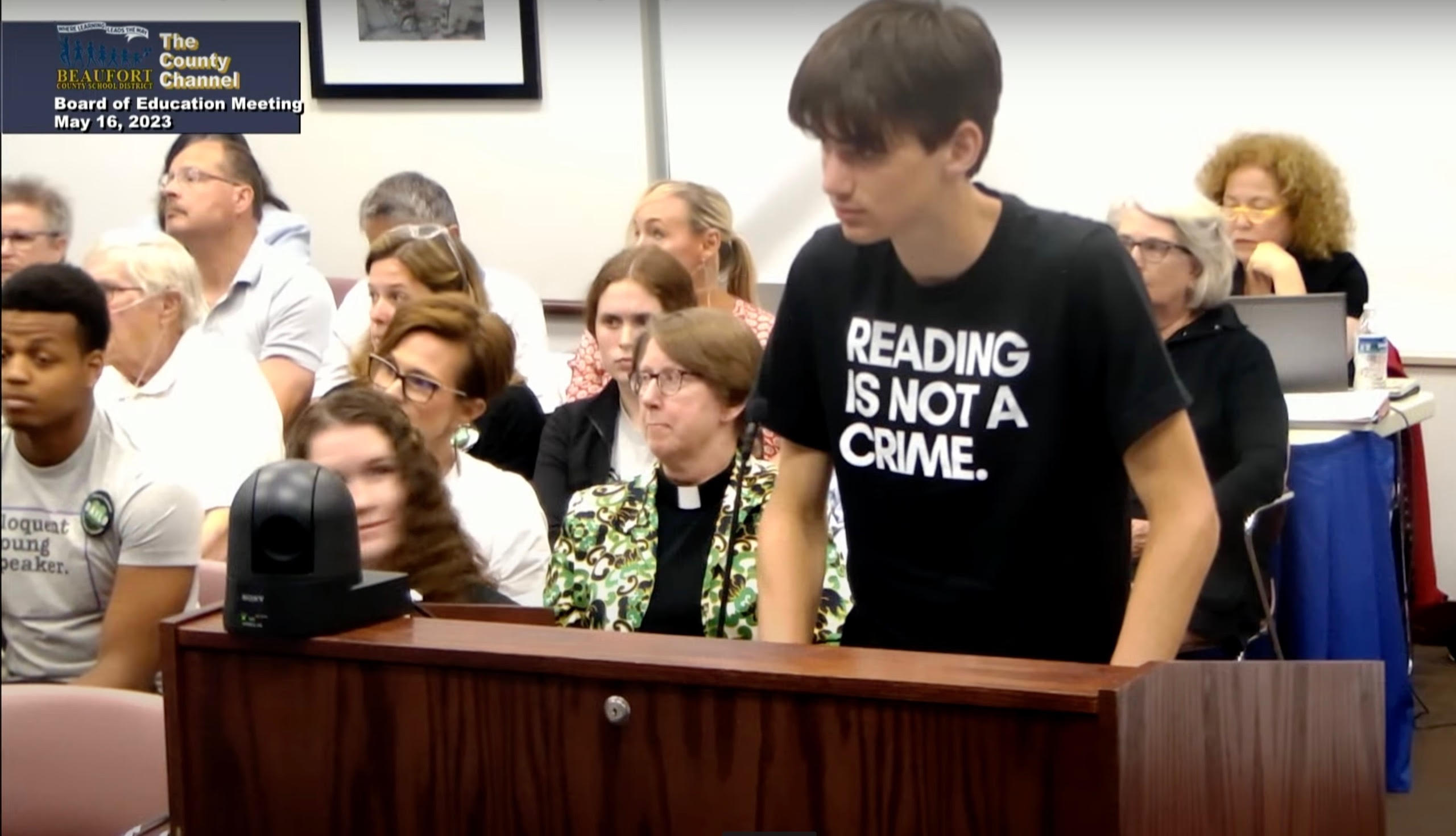

PG: One of the obstacles I think we see a lot as students is just getting respect. At the state board [of education], we had somebody say, “Why should we trust students? I know I did a bunch of stupid stuff when I was a teenager. Why should we listen to them?” Another student named Izzy, and I use this quote a lot, said, “My voice is silent. My screams are a whisper.” As students, we have to speak twice as loudly, twice as eloquently, just to get heard at the normal voice or sound that an adult would.

MR: I feel like anytime any of us speak about something legitimate that goes on with book banning, it’s always met from the other side — I hate to be polarizing, but people that are for the book bans — saying it’s porn. I feel like that’s the main argument… And I just think it’s so horrible. My biggest gripe with them is that they read aloud scenes of like rape and incest, and it’s just disgusting. I mentioned this once when I spoke out at my county’s school board of education, but to call incest and rape porn… It’s just horrible. It’s so bad.

DR: It is a very polarizing issue. There isn’t much in the way of compromise or education, and some of the meetings have been terrifying, because you’re three or four kids in a room full of people who ultimately get up and start screaming at you. It’s not an easy thing to do, but I would say I’ve seen some of the quietest students at our school get up and speak in front of these hateful crowds, and it’s impressive. It brings out the best side of people, but also the worst.

MR: I was going to say, when I spoke in my county … a police officer came up to me, and he was like, “Hey, just so you know, I’ve got your back. I’ll make sure no one comes up to you.” And I was just kind of like, “You shouldn’t have to say that.” But I was thankful that he did do that. It can be scary to go up and speak there.

You’re featured in the documentary Banned Together, which explores the rise of book bans and education censorship in South Carolina as well as efforts to combat them. Who are you hoping goes to see the documentary? What are you hoping they take away from it?

PG: I’m hoping the people that go to see it aren’t the people that have been following our journey and following book bans. They’re your average American who’s sitting on their couch watching TV and sees a documentary pop up, and they just learn about everything that’s happening in our country and start to get involved with it. There are so many students and parents — even my parents’ friends or grandparents’ friends — and we’ll just be having a conversation, and I’ll tell them about this, or it’ll just be mentioned casually, and they’re like, “What? This is happening in our county?” They’ll just have no idea. So I just hope more people learn about this, because there’s been a lot of ignorance about book bans specifically.

What are your hopes for the future of DAYLO?

MR: I hope it becomes everywhere. I hope everyone at schools that is super into reading — because I know that there are a lot of people like that, they’re just not loud about it — I hope they can get involved in the club. People that have not been exposed to as much diversity as others can learn a lot from reading these books. I hope it’s not an advocacy thing forever. I hope we don’t have to keep fighting book bans. I hope it can be an awesome book club, where people get to learn about other people’s lives. Growing would be really cool.

DR: I’m with Mary on that. I’m always happy and willing to do the advocacy portion of it, but it would be nice if we got to a point where, rather than dedicating the majority of our resources and time to that, we could dedicate it to expansion and the original intent, which is using literature to discuss issues and spread awareness. It’s pretty horrible that we’ve had to shift our focus just to keep books in school. I hope that one day we can get to a point where that isn’t what we have to do.

PG: For me, DAYLO feels really big right now because I joined when there were two chapters. The president of Beaufort High’s chapter’s mother was our school’s librarian, so it was founded here, and it never felt like DAYLO was going to get bigger. It was just two schools because of that relationship, and all of a sudden, it’s [10] chapters now… Like [Mary and Dylan] said, I hope DAYLO doesn’t have to be an advocacy thing forever. But with a lot of recent news that I’ve heard, I don’t expect that to go away so quickly.

What advice would you give to students who are concerned about growing censorship and book bans within their school districts?

MR: I would find an English teacher. I would find an English teacher that you know is cool and start your own DAYLO. And find kids that like to read. … Find a group of like-minded individuals, and then reach out to the non like-minded individuals so they can learn about DAYLO.

DR: Books are such a powerful thing. It’s a very easy community to create, even if it’s just, like Mary said, talking to one teacher.

MR: It’s always the cool English teachers.

And my final question: What is your favorite banned book?

MR: A Thousand Splendid Suns [by Khaled Hosseini]. I really like that book.

DR: My goal is to read all of them. But if we’re talking the list of 97, it would probably be The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo.

PG: The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. I don’t think I would say it’s my favorite book or that it’s the first book I would go to on my shelf to read again, but that book has changed who I am as a person more than I thought a book could. It continues to be one of my main inspirations for why I fight so hard for this.