Banned in the USA:

Narrating the Crisis

PEN America Experts:

Program Director, Freedom to Read

Senior Program Manager, Freedom to Read

Program Coordinator, Freedom to Read

Senior Advisor, Freedom to Read

The book ban crisis is often referred to by its numbers. A rising number of bans, more states impacted, more titles implicated. And behind every number, there is a deeper story: the narratives being censored from pages, the overworked librarians and teachers, the authors whose work has been maligned, and the students who see their identities and their opportunities to learn about other experiences and histories swept from shelves.

This report provides data, alongside a comprehensive narrative of the censorship crisis affecting public schools. It shows the nuance of the current moment and damage that occurs when stories—compassionate, reflective, educational, and entertaining—are restricted or removed on the basis of fear, intimidation, or bigotry.

Key Findings:

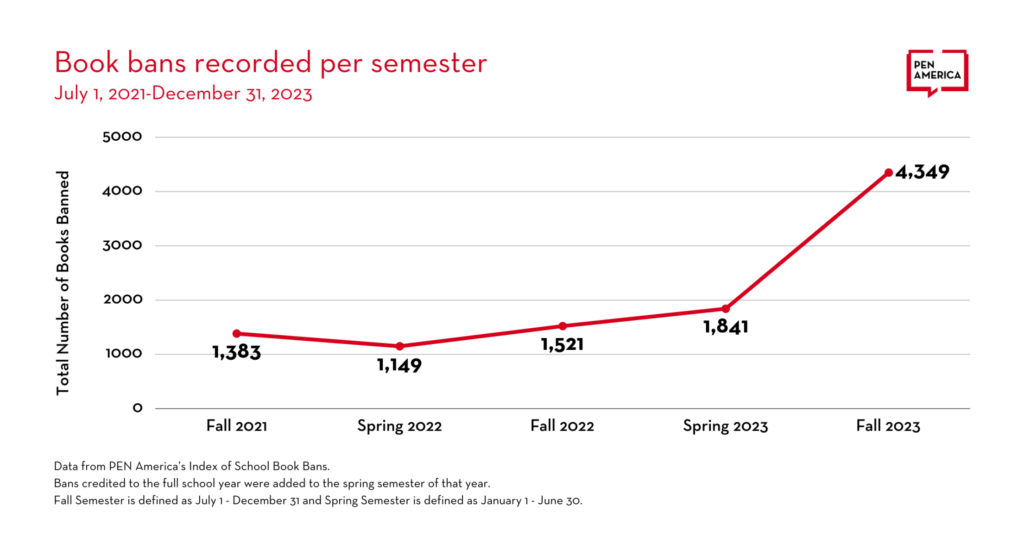

The bans are speeding up. There were over 4,000 instances of book bans in the first half of this school year—more than all of last school year as a whole. This is a marked increase in comparison to the last spring semester, in which PEN America recorded 1,841 book bans.

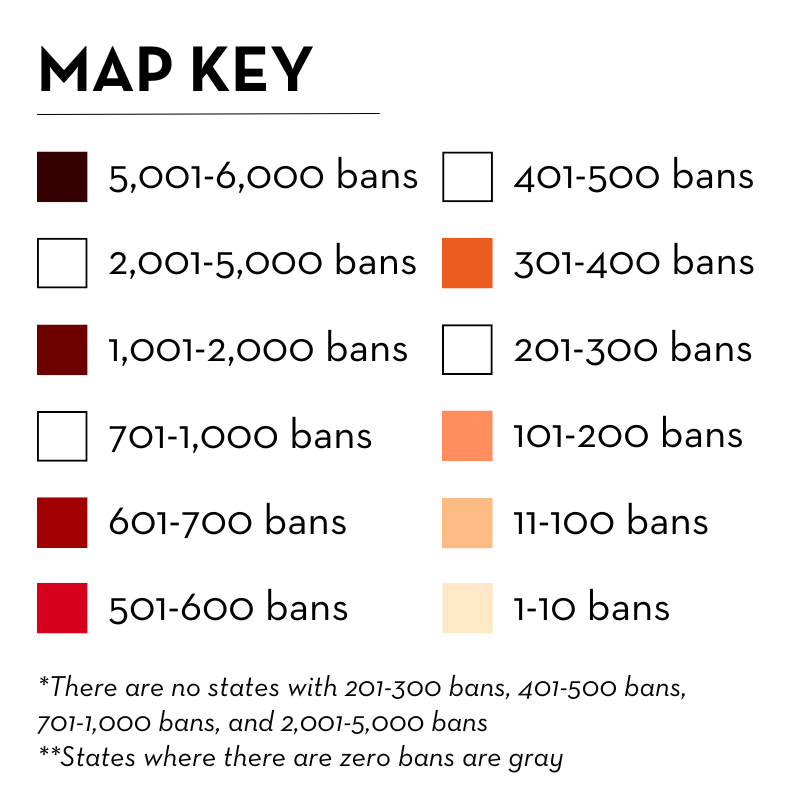

It’s a nationwide campaign: over the last two and half academic years, PEN America has recorded banning activity in 42 states, across red and blue districts.

Those who want to ban books are attempting to use obscenity law and hyperbolic rhetoric about “porn in schools” to justify banning books about sexual violence and LGBTQ+ topics (and in particular, trans identities). In doing so, they have also disproportionately targeted books by women and nonbinary authors.

The movement to ban books also continues to focus on themes of race and racism by advancing rhetoric disparaging “critical race theory,” “woke ideology,” and efforts to ensure library collections are diverse and inclusive.

Even so, resistance is rising, and the very students whose right to read is being challenged and the authors whose works are being censored are fighting back in creative and powerful ways.

4,349

The instances of book bans that PEN America recorded in fall 2023

Fall Semester is defined as July 1 – December 31.

The State of School Book Bans in the USA: An Overview

PEN America recorded more school book bans during the first six months of the 2023-24 school year than in all of 2022-23. This escalation follows two years of coordinated efforts to censor books in libraries and classrooms across the country, restricting young people’s freedom to read and learn. In the third consecutive year of this attack on books and ideas, this organized effort has commandeered school and library boards, city councils, and state legislatures in an unprecedented effort to extend ideological control over public institutions and ban books by any means necessary.

This report provides a preliminary look at the current school year. We provide a data summary of book bans from July 2023 to December 2023 and identify key trends in the kinds of books that are being targeted.

In addition to data-driven trends, the report utilizes case snapshots to illustrate the rhetoric driving book bans and personal damage that this movement has done to students and communities alike. These snapshots, which draw from school districts across the country, provide vital context for the overwhelming number of book bans that have saturated the country since 2021.

Each section of this report illustrates one key trend in the nationwide effort to disrupt public education. This includes targeting books about sexual violence and rape, books about LGBTQ+ identities and experiences, and books with characters of color or that explore themes of race and racism. The report also seeks to demonstrate how these bans frequently occur against the recommendations of review committees, as well as against the wishes of individual students, parents, and community members.

As censors continue to dig in their heels, and as book bans spread to ever more districts nationwide, hope remains. Galvanized by the actions of the very students most impacted by book bans, a broad coalition of educators, librarians, parents, authors, and advocates are organizing in ways large and small to protect the freedom to read.

History of The Ed Scare

Beginning in January 2021, a wave of educational gag orders began to sweep state legislatures, attempting to prohibit specific content related to race, gender, and sexuality from both classrooms and trainings. This swell of bills began as part of a broad backlash against the racial reckoning within institutions that ensued after the publication of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s 1619 Project in the New York Times in 2019 and the murder of George Floyd in 2020. The same year, a broader campaign unfolded, including not only legislative proposals but coordinated efforts to ban books in public schools and libraries. PEN America has characterized this movement to exert ideological control over educational institutions as the “Ed Scare.”

As part of this movement, the language of “parental rights” has been employed as a rhetorical tool to advance bills and policies that make it easier to ban books and object to curriculum on political grounds. While “parental rights” rhetoric has a long history, it was widely adopted within the Republican Party after Glenn Youngkin successfully campaigned under its banner in Virginia’s 2021 election for governor.

Elsewhere on the political right, restrictions on content and books are framed as a way of resisting supposed liberal “indoctrination,” sometimes invoking conspiracy theories about sexual “grooming.” In these unfounded accusations, “grooming” refers not only to pedophilia but routinely to LGBTQ+ teachers and librarians who are falsely purported to be “indoctrinating” children into an LGBTQ+ “lifestyle”—a charge rooted in homophobia.

For more history and background on “parental rights” rhetoric and the Ed Scare, please read PEN America’s 2023 report Educational Intimidation: How “Parents’ Rights” Legislation Undermines the Freedom to Learn.

Data Snapshot

From July 2023 to December 2023, PEN America recorded 4,349 instances of book bans across 23 states and 52 public school districts. These newest numbers represent a significant increase compared to previous tracking: more bans have been reported in the first semester of this school year than all of the previous school year, in which 3,362 books were banned. Collectively, the fall’s bans impact millions of students.

Since July 2021, PEN America has recorded book bans in 42 states. These bans have frequently occurred as a result of state legislation and/or activity from groups like Moms for Liberty. This past fall, districts across the country have continued these trends, and the bans have far outpaced previous semesters.

Cumulative book bans in the United States, July 1, 2021 – December 31, 2023

Florida experienced the highest number of ban cases, with 3,135 bans across 11 school districts. Over 1,600 of those book bans took place in Escambia County Public Schools, the district with the most bans nationwide. But the crisis is not limited to Florida. Wisconsin experienced the second-highest recorded bans, reporting 481 bans in three districts; the vast majority of these bans occurred in the Elkhorn Area School District, which banned 444 books following a single parent’s challenge. Iowa cracked into the top three this fall, with 142 bans in three districts. Texas was close behind, with 141 bans across four districts. Two more states, Kentucky and Virginia, each experienced at least 100 bans: in Kentucky, Boyle County Schools removed 106 books on its own, and in Virginia, these 100 bans occurred across three school districts.

Trend 1: Censorship of Sexual Violence

Case District: West Ada School District, Idaho

Takeaway: The book banning movement explicitly targets books featuring scenes or themes of sexual violence by weaponizing the concept of “obscenity.” Aided by websites like Book Looks, activists seek to ban books about rape and sexual assault. In doing so, they cut off a vital lifeline for students and target books that disproportionately impact women and nonbinary authors.

What world do we have right now that we don’t want our young people to understand … what sexual consent is?

A Kentucky parent after Sexual Consent by Martin Gitlin was banned in their district

Since the current wave of book bans began in 2021, sex in books has commonly been used as grounds for removal. Objectors have described books as “pornographic,” “disgusting,” and “obscene”; in August, one woman in Pennsylvania even accused school officials of “sexually abusing” her granddaughter by making several book titles available. Further, legislation and district policies have placed prohibitions on materials considered “sexually explicit” or “sexually relevant” or including “sexual conduct.” The result of such inflated rhetoric and accompanying prohibitions is books being banned for including sex, abortion, or rape, with women and nonbinary authors frequently among those most censored.

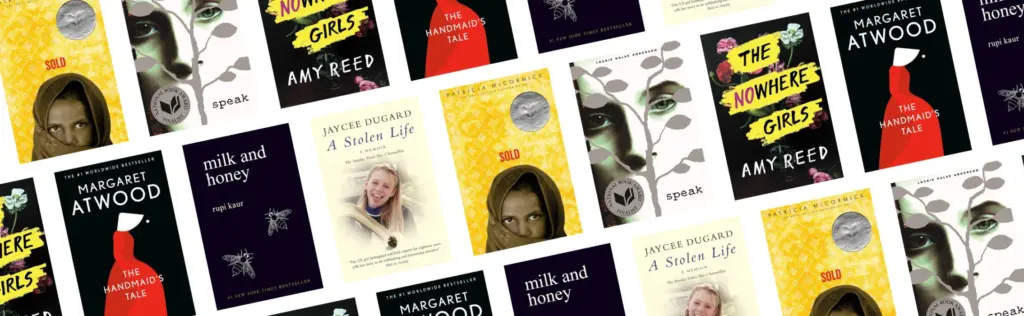

For example, the trustees of the West Ada School District in Idaho voted to remove from shelves The Nowhere Girls by Amy Reed in November 2023. The book centers three teenage girls who create a group to “resist the sexist culture at their school” after learning about another girl who was run out of town for accusing boys at school of gang rape. According to the trustees in West Ada, The Nowhere Girls is a “vulgar and obscene” book that teaches teen girls to think revenge is an appropriate response to rape.

The Nowhere Girls was banned alongside at least ten other titles, including books by Sara Gruen and Sarah J. Maas. Also banned was A Stolen Life by Jaycee Dugard, a memoir detailing her kidnapping, sexual abuse, and survival, as well as two books of Rupi Kaur’s poems, which similarly deal with rape and sexual violence. Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, a feminist dystopian novel about rape and forced birth, was also banned. When reviewing the books, the district used excerpts from a website called Book Looks, which is frequently used by those who challenge books.

Like in West Ada, many have attempted to add a legal justification for their bans by characterizing specific works in schools and libraries as “obscene,” a category of speech that is not protected under the First Amendment. These claims are not supported. The legal threshold for obscenity was decided by the Supreme Court in Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973), which created a three-pronged test for obscenity: the so-called Miller test. To satisfy the test, a work must be “taken as a whole” and found to lack “serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.” However, to circumvent these actual legal requirements, states and districts have increasingly introduced new terms or manipulated other existing statutes instead.

A book that negatively depicts rape culture and empowers students to stand up for themselves is one that all high school students should have access to.

A Kentucky parent after Sexual Consent by Martin Gitlin was banned in their district

Those banning books, from the legislature or via challenge form, commonly seek to apply definitions of “sexually explicit” materials or “sexual content” to books as rationale for censoring them. These terms share no consistent legal definition from state to state and can be interpreted expansively, leading to confusion about what is and is not allowed. The result is that many of the materials now being targeted for their sexual content are not being evaluated according to the existing legal definition of obscenity. In the rush to label everything as obscene, works like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower, and even Merriam-Webster’s Elementary Dictionary have been banned, despite their obvious literary value.

This abuse of the concept of obscenity is never clearer than when examining challenges to books about sexual assault and rape.

What Is Book Looks?

Book Looks is a website that was created by a former member of Moms for Liberty in 2022. The website includes information on a wide array of book titles, offering a rating from 0 to 5 for “objectionable” content, paired with quotes from the text without any context. The website includes neither synopses of titles nor professional reviews or awards, and it does not review books holistically in a manner consistent with the Miller test. It flags only selective content, such as violence, profanity, gender identity and sexual orientation, and “inflammatory” commentary regarding race.

The website has been cited by groups nationwide in their book challenges and has even been incorporated into some districts’ official book review policies. It is frequently used by groups like Moms for Liberty to advance bans on books based on selectively chosen excerpts. Such was the case in Carroll County, Maryland, where local members of Moms for Liberty utilized Book Looks to challenge over 50 books, resulting in bans or restrictions for at least nine books. According to one analysis, 96 percent of the books challenged by Moms for Liberty in Carroll County included sexual content and 36 percent contained references to rape. The site has effectively been used to target censorship of these topics on a widening scale.

I cannot imagine my childhood without a library or without books, or without knowing that I had the possibility to explore different worlds.

A student in West Ada responding to book bans in their school

According to PEN America data from the 2021–22 and 2022–23 school years, 19 percent of books banned through June 2023 include depictions of rape and sexual assault. Many of these books were specifically written for young adult audiences; YA as a genre commonly explores challenging topics, including sexual assault and rape, to help educate young readers and in some cases to help them understand their own feelings or experiences. And when it comes to sexual assault, that understanding can be crucial: according to RAINN, 1 in 9 girls and 1 in 20 boys under the age of 18 experience sexual abuse or assault. For those millions of students, books can be a lifeline.

In response to her book Milk and Honey being banned across the country, poet Rupi Kaur said on her Facebook page, “i remember sitting in my school library in high school, turning to books about sexual assault because i didn’t have anyone else to turn to.” This is a sentiment that has been echoed by authors like Laurie Halse Anderson (author of Speak) and Patricia McCormick (author of Sold) in interviews with PEN America and the New York Times; Speak and Sold have each been banned repeatedly in recent years.

This is also a sentiment that has frequently been expressed by school librarians and teachers to oppose these bans. In West Ada, high school librarian Gena Marker testified to the board that The Nowhere Girls helped students “empower themselves in the face of adversity.” She went on to say, “A book that negatively depicts rape culture and empowers students to stand up for themselves is one that all high school students should have access to.”

The board voted to remove The Nowhere Girls anyway, despite the recommendation from the district reconsideration board to retain the book. In total, 9 out of the 11 of the books banned in West Ada this fall were by women. More than half contain narratives about sexual violence or violence against women.

The trend toward censoring literature about rape is not isolated to Idaho: in Kentucky, the nonfiction book Sexual Consent by Martin Gitlin was banned for several weeks in one district, prompting one parent to wonder, “What world do we have right now that we don’t want our young people to understand . . . what sexual consent is?” In Collier County Florida, one book about sexual violence, Ink Exchange by Melissa Marr, was removed under HB 1069. The law makes it easier to pull a book that “depicts or describes sexual conduct” from school shelves; because of the lack of clarity around how to implement the law, the book was banned despite the fact that the rape at the center of the narrative is never directly described.

Banning books about sexual violence, either through administrative processes in response to legislation or in response to challenges and out-of-context excerpts, does a disservice to the students who have a right to access that information. One student in West Ada said she felt “helpless” after the autumn’s bans. Another said, “I cannot imagine my childhood without a library or without books, or without knowing that I had the possibility to explore different worlds.” Those banning books seek to restrict those possibilities for these students under the guise of protecting them from obscenity.

Trend 2: A Continued Hostility Toward LGBTQ+ Books

Case District: Boyle County Schools, Kentucky

Takeaway: Another casualty in the campaign against “sexually explicit” content has been LGBTQ+ narratives. Entrenched stereotypes about LGBTQ+ people as inherently sexual or inappropriate have been rolled into legislation policing “human sexuality” in schools, creating a catalyst to spur book bans nationwide.

Alongside a hostility to works about sexual violence, the national book banning movement has generated a potent resistance to representations of gender identity and sexuality in K–12 schools. Books with LGBTQ+ characters and themes made up 36 percent of all bans from 2021 to 2023, and many of the most prominent banned books of the past three years, like Flamer by Mike Curato and Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe, center narratives of LGBTQ+ experiences.

As PEN America has documented, the shift toward vague laws that prohibit curricular topics or library materials has been a key tactic nationwide. HB 1557 in Florida, dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law, provided one such template. Its prohibition on instructing students about sexual orientation or gender identity has been widely interpreted as a directive to ban thousands of books in the past two years. In March 2023, Kentucky became one of the states to follow Florida’s lead by passing SB 150, an expansive educational gag order that prohibits instruction about “human sexuality” before sixth grade, and instruction on “gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation” in any grade.

The following September, Boyle County Schools in Kentucky quietly removed over 100 books from the library that they believed violated SB 150. Nearly all of them were about LGBTQ+ characters, history, or identity.

Titles banned in Boyle County for violating SB 150 included history and sociology books like LGBTQ+ Athletes Claim the Field: Striving for Equality by Kirstin Cronn-Mills, Stonewall: Breaking Out in the Fight for Gay Rights by Ann Bausum, Gender Equality and Identity Rights by Marie des Neiges Léonard, and Anne Frank: The Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography by Sid Jacobson and Ernie Colón. The law similarly ensnared fiction titles like Too Bright to See by Kyle Lukoff, Aristotle and Dante Dive into the Waters of the World by Benjamin Alire Sáenz, and Hurricane Child by Kacen Callender.

It promotes one to act on impulse, desire and feeling. It is also promoting the lesbian lifestyle.

A Virginia parent objecting to Valiant Ladies by Melissa Grey

A lack of clear guidance from the state board of education about how to implement SB 150 led to confusion about what kinds of books the law applied to. In an October 2023 interview with a local Kentucky newspaper, Boyle County Schools superintendent Mark Wade said that the district removed the books in response to the law after failing to receive clear guidance from the state. In November, after robust student and parent pushback, the Kentucky Board of Education clarified that the law doesn’t apply to library books after all, resulting in Boyle County returning books to shelves.

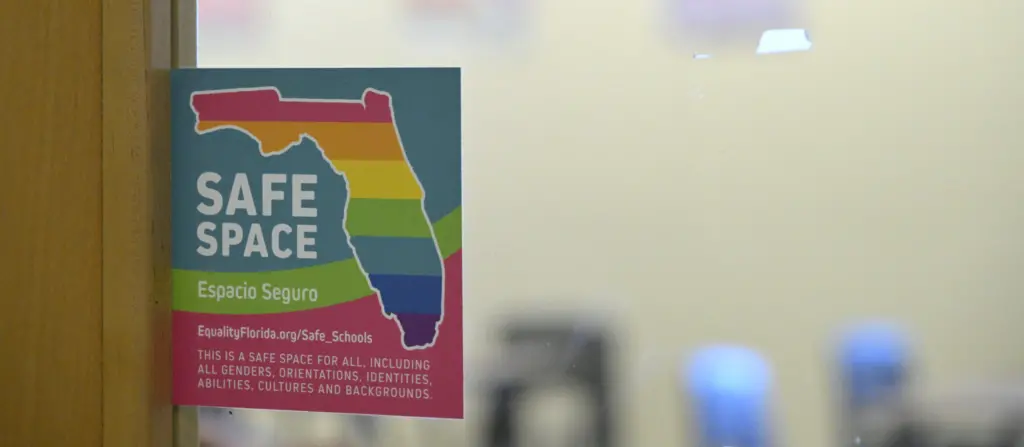

At least six states have laws or policies similar to SB 150. And still more states, like Montana and Tennessee, have laws requiring schools to notify parents in advance of any instruction related to sexuality or gender so that they can opt their children out; such laws often encourage teachers to avoid those topics altogether. While the original “Don’t Say Gay” law in Florida was recently clarified in court to refer only to curriculum and formal instruction, the vagueness of the original law resulted in two years of uncertainty where large swaths of books were banned from libraries and classrooms for containing gay characters while LGBTQ+ “Safe Space” stickers were removed from classroom doors. In Charlotte County, Florida, the superintendent instructed librarians in July 2023 to remove all books with LGBTQ+ characters in an effort to comply with the law.

The erasure of LGBTQ+ stories in schools is a result not just of vague legislation, as in Kentucky, but also of book challenges from parents and activists. In November, an Oregon school district reviewed 18 book challenges, each involving books about LGBTQ+ characters or themes. Ultimately, 11 were restricted to high school libraries only, and one, Kacen Callender’s YA rom-com This Is Kind of an Epic Love Story, was removed entirely. In one Virginia county, Melissa Grey’s Valiant Ladies was banned after a parent challenged it for “promoting the lesbian lifestyle.” In Ohio, an author’s book reading was canceled after a parent accused him of “coming with an agenda to recruit kids to become gay.” And in one California district, a parent’s challenge to This Book Is Gay by Juno Dawson resulted in the closure of every school library in the district’s 23 campuses as media specialists audited their collection.

As many districts increase the availability of diverse and inclusive books in their school libraries, books with LBGTQ+ characters and themes are overwhelmingly targeted for removal, with book challengers often citing long-standing stereotypes that stigmatize and dehumanize LGBTQ+ people as inherently sexual or “inappropriate.”

Trend 3: Transgender Narratives in the Crosshairs

Case District: Troy City Schools, Ohio

Takeaway: Transgender identities and narratives are under particular scrutiny. A barrage of legislation policing gender expression in schools and heightened rhetoric about the alleged harms of “gender ideology” have resulted in disproportionate bans on books that include trans characters and antagonistic environments for trans students.

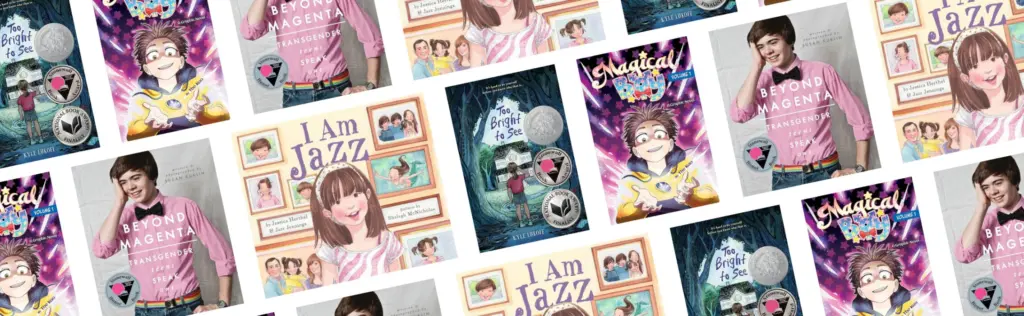

Some LGBTQ+ books have faced particular scrutiny. The book banning movement has featured a widespread and consistent attack on trans students, trans stories, and trans authors. At least 8 percent of all books banned between 2021 and 2023 featured transgender characters or narratives.

In addition, at least nine states have passed laws that would result in students being outed to their parents without their permission if they request changes to their name or pronoun, or if a teacher suspects a change in their gender identity. Advocates have tracked an avalanche of anti-trans legislation, targeting everything from educational content to bathroom access to medical care.

The focus on transgender narratives in some districts has been especially acute. This was the case in the Troy City Schools in Ohio, where a local resident searched the term “transgender” in the library’s online catalog and challenged the nine books that were returned in the search.

The August 2023 review resulted in the removal of Beyond Magenta by Susan Kuklin, a book composed of interviews of transgender teenagers. The committee also decided to move Magical Boy by The Kao to high school libraries only. Several books examining gender norms were challenged but ultimately remained on the shelf, including Middle School’s a Drag: You Better Werk! by Greg Howard, which the challenger said “promotes drag queen performances” to young teens. Of the challenge, superintendent Chris Piper said, “This is the first time in my career, and the first time that any of us here in Troy City Schools have dealt with it.”

A similar focus on suppressing transgender stories and identities has gained traction nationwide—in both schools and public libraries—propelled by politicians, provocateurs, and right- wing think tanks. One legislator in Alabama explained that his version of the “Don’t Say Gay” law was in fact necessary because while “gay people have been around since the beginning of time,” action is needed to prevent the “new fad … to push people towards this transgender.” The Heritage Foundation has stated that books like I Am Jazz by Jazz Jennings “[promote] transgenderism”—and therefore have no place in schools. And Chaya Raichik, the mind behind Libs of TikTok, has called teachers “abusive” for teaching about gender identity. Raichik has since been appointed to the statewide Oklahoma Library Media Advisory Committee, a position from which she can further advance this ideology.

According to the Trevor Project, 64 percent of transgender and nonbinary young people reported that they have felt discriminated against in the past year because of their gender identity. Further, anti-LGBTQ+ policies and legislation applied in schools have demonstrable impact on the mental health of LGBTQ+ teens. The Rainbow Youth Project, a nonprofit that operates a crisis call center for LGBTQ+ youth, reported more calls in 2022 about caustic political rhetoric and legislation than about bullying. According to the Washington Post, hate crimes against LGBTQ+ students have skyrocketed in states with restrictive gender policies or “Don’t Say Gay” copycat laws.

Book bans targeting trans narratives and trans authors, alongside restrictive legislation and aggressive political rhetoric, contribute to a school environment that is antagonistic toward trans students, and where the very stories that could foster understanding and empathy for trans peers are inaccessible for all.

Trend 4: “Critical Race Theory” Backlash

Case District: Lexington School District Two, South Carolina

Takeaway: An overwhelming number of books about race and racism have been banned since 2021. Since the beginning of the current movement, inflated rhetoric about “critical race theory” and “wokeness” has aided a coordinated attempt to whitewash American history and remove diverse books from shelves.

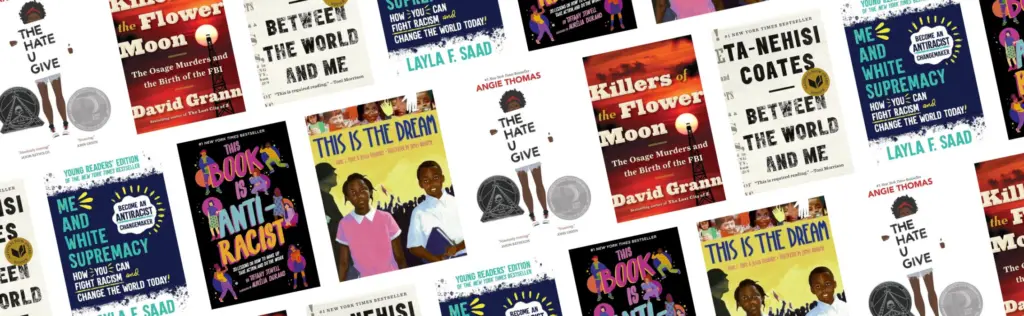

Books about race and racism, and books with characters of color, were the targets of 37 percent of all book bans in the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years. The rhetoric directed at these books has mutated since 2021; such works were initially framed by opponents as “critical race theory” (CRT). Led by right-wing think tanks, the anti-CRT rhetoric framed discussions of race and racism in schools as “divisive,” claiming that discussing race at all actually causes racism. More recently, books about race or characters of color have also garnered criticism for advancing “woke ideology” or “DEI.”

Over the course of this ongoing campaign, the censorship net has captured a wide variety of books related to race. This includes texts discussing social justice movements like Black Lives Matter, as well as books with protagonists of color or historical nonfiction, like a book about the creation of the Ku Klux Klan and a picture book about desegregation efforts in California.

I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina.

A high school student objecting to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ National Book Award-winning memoir Between the World and Me

This trend is particularly visible in South Carolina, where in 2021 the state attorney general wrote a letter to the federal government protesting “critical race theory,” accusing the education department of promoting “Marxism,” and accusing author Ibram X. Kendi of fomenting “racism” in educational institutions nationwide. At least eight school districts in the state have enacted their own versions of anti-CRT policies, and the state legislature has thrice passed budgets prohibiting state funds from being used to promote “divisive concepts.”

In Lexington-Richland School District Five, these educational gag orders resulted in the school board and principal instructing an AP English Language teacher to remove Ta-Nehisi Coates’s National Book Award winning memoir Between the World and Me from her curriculum in June 2023 because some white students said it made them “ashamed to be Caucasian” and “incredibly uncomfortable.” One student claimed that the removals were justified under law, remarking, “I am pretty sure a teacher talking about systemic racism is illegal in South Carolina.”

This school year, in September 2023, 17 books were also removed from school libraries in nearby Lexington School District Two after a local group called Parents Advocating for Children’s Education (PACE) challenged their presence in local schools. PACE members challenged books for allegedly teaching children that they need to defeat their “inner white demon” and for containing topics like white privilege and “racially and politically divisive material.” In total, PACE challenged 30 books, resulting in 17 being removed and 3 being restricted to high school shelves. The group referred to the process as a “detox.”

Books removed entirely from shelves include Me and White Supremacy: Young Readers’ Edition by Layla F. Saad; Rise Up! How You Can Join the Fight against White Supremacy by Crystal Marie Fleming; and This Book Is Anti-Racist by Tiffany Jewell. The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas was restricted to 11th and 12th graders.

Alongside books about race and racism, and books that feature characters of color, a range of books about sexual health (like It’s Perfectly Normal by Robie H. Harris) and about gender (like They, She, He, Me: Free to Be! by Matthew Smith-Gonzalez and Maya Christina Gonzalez) were also banned in Lexington Two as a result of PACE’s challenge, mirroring national trends. The books challenged by PACE, but not removed, include The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison and Bathe the Cat, a picture book by Alice B. McGinty that portrays a family with two fathers of different races.

Several of the banned or restricted books in Lexington Two were written or republished following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. That year, activists, librarians, and booksellers produced dozens of lists of books about race and racism to help kids and teens understand the cultural and political moment, as well as the impact of police violence on Black communities. Dubbed “the George Floyd Effect” by Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow, the wellspring can be understood as a concerted effort by publishers and educators to meet the need to explain questions of racism, police violence, and privilege. But not long after the proliferation of this material, the backlash against “critical race theory” crystallized on the political right, leading to many of these books being challenged or banned from public schools.

This intense focus on silencing speech about race can be seen nationwide and has continued this school year. In Florida, local journalists have reported that one Leon County teacher no longer teaches This Is the Dream, a picture book by Diane Z. Shore and Jessica Alexander about Martin Luther King Jr., because she fears it may be against the law. In October 2023, a parent in Illinois successfully lobbied the Yorkville school board to remove Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson from the curriculum after board members declared the book about two wrongfully convicted Black men “too controversial.” In Oklahoma, teachers are unsure whether they can assign David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon under the state’s educational gag order, despite the fact that it chronicles the history of the Osage Nation in the state.

With each new law, each new challenge form, and each new policy prohibiting “critical race theory,” stories that depict and uplift voices of color are restricted and the breadth of ideas available to students continues to narrow.

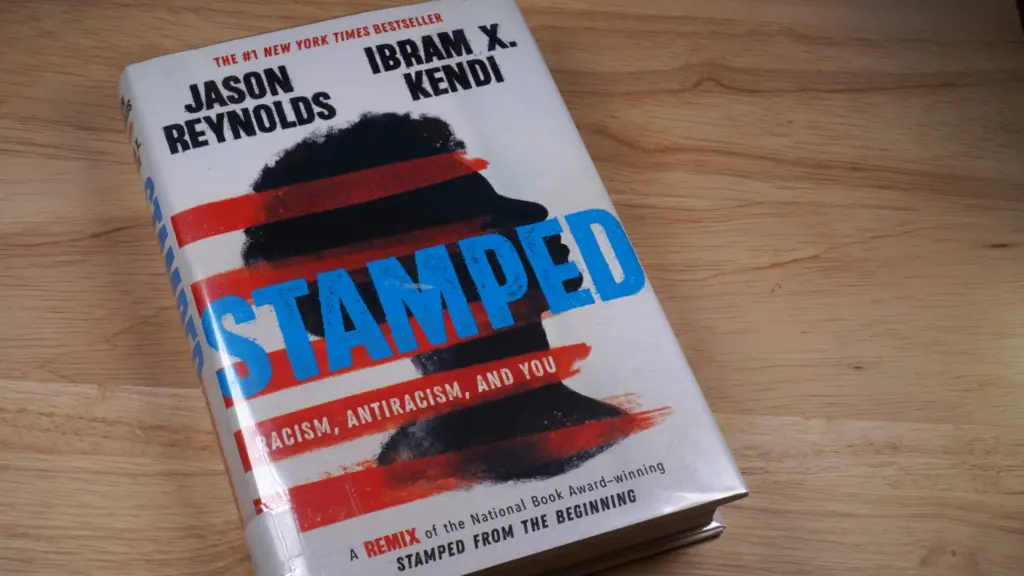

This book contains Marxist ideology, inaccurate reframing of history, untruths, and disrespect for our nation and the Bible.

A parent objecting to Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

Trend 5: Vocal Individuals or Small Groups Disempower Parents and Students

Case District: New Hanover County Schools, North Carolina

Takeaway: The book banning movement proclaims to advance “parental rights” but actually advances a censorial agenda. Coordinated efforts by a small group of individuals and organizations have created an environment of intimidation in public schools that has supercharged book bans, over the objections of most parents, teachers, and students.

Much of the recent book banning activity in the United States has occurred under the banner of “parental rights.” This narrative persists despite ample evidence that the movement generally works against the will of most parents. There is no clearer example of this than in Hanover, North Carolina.

In September 2023, the school board in Hanover voted to restrict access to Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi following a challenge from a local parent, who accused Stamped of being “rooted in untruths about our nation and from a twisted and biased perspective on American History.” The objector claimed the book, which was included in the AP English curriculum, teaches Marxism and critical race theory. According to the course instructor, the book was included in the college-level course to help students analyze its rhetoric and arguments and whether they were effective. Other works assigned in the class included Ronald Reagan’s inaugural address and a speech by Mitch McConnell.

Only one parent formally objected to Stamped, even after the instructor allowed that parent’s child to read a different book instead. The media review committee at the high school found the book suitable for inclusion in the AP course, and the parent lost her appeals. Even so, when the parent took the complaint to the school board, they reversed the decisions of the committee. The board decided to keep the book available in the library, but to remove it from the curriculum for AP Language and Composition students.

The removal of Stamped from the curriculum happened despite pushback from community members in New Hanover, and against trends in public opinion more broadly. According to a 2022 poll from education policy journal Education Next, 77 percent of parents think the emphasis on slavery or racism in public schools is either “about right” or “too little.” Further, according to a 2024 report from the RAND Corporation, over half of teachers reported self-censoring when speaking about race out of fear of parental disapproval, even in states without legal restrictions on classroom content and instruction.

The influence of groups like Moms for Liberty—whose members make up the majority of the Hanover school board—is unmistakable. Alongside inflammatory rhetoric from politicians and censorial legislation, this has created a teaching environment that caters to the loudest voice in the room and favors censorship over ready access to literature.

In claiming to advance “parental rights,” those intent on banning books seek to impose their viewpoints on all parents in a district. This inherently undemocratic trend is intensifying, leading to more bans and an impaired environment for student learning.

It is important for school boards to remember the voice of the students is the most important one because that is who they are serving.

Alaska Association of Student Governments in a resolution opposing book bans

Trend 6: There’s Hope—Resistance is Rising

Case District: Nationwide

Takeaway: Students in districts nationwide have been instrumental in efforts to roll back book bans. Student resistance exemplifies a broader trend, also seen in legislation and the courts, to fight back against encroachments on the freedom to read and learn.

Students have been at the forefront of the fight for the freedom to read, even as they feel the immediate and harmful impacts of the book banning movement.

In the fall of 2023, approximately 650 students students staged a walkout in Alaska’s Matanuska-Susitna (Mat-Su) Borough School District to protest the school board’s decisions to remove the student representative from the board and to investigate challenges to 56 books. As part of the review, the board recommended several books be removed or restricted, including Robie H. Harris’s It’s Perfectly Normal and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. The students’ walkout lasted 56 minutes: one minute per book challenged.

The Alaska Association of Student Governments, a statewide organization of student leaders committed to providing a student voice “at the local, state and national levels,” took notice: the organization cited the Mat-Su bans in their resolution condemning book bans across the state. In the resolution, members reminded local politicians that “the voice of the students is the most important one.”

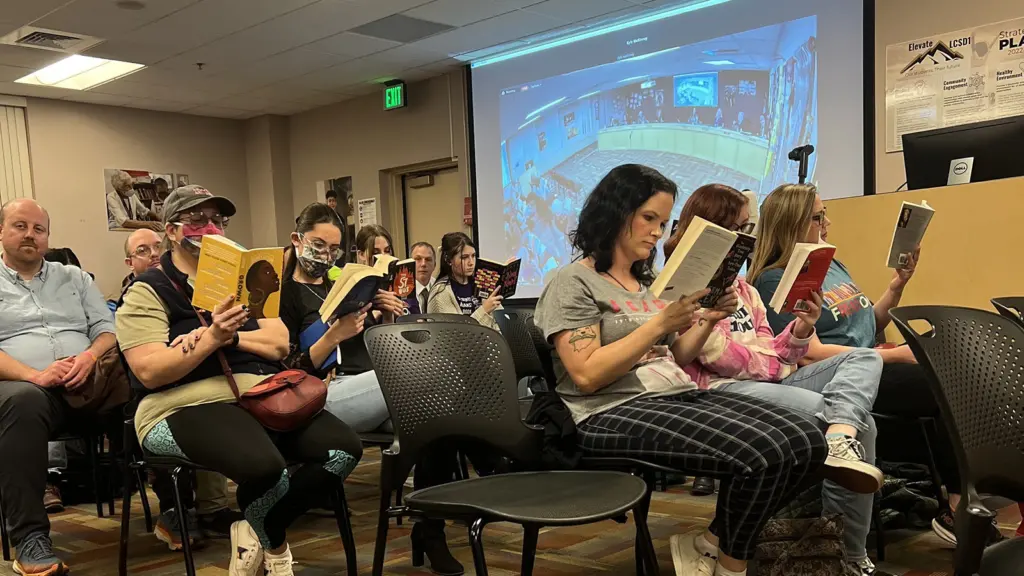

In Laramie County, Wyoming, students staged a “read-in” at an October meeting where the school board was contemplating an opt-in policy for checking out certain books at the library. The silent protesters read books like Grown by Tiffany D. Jackson and A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas—titles that have been challenged and deemed obscene across the country. “It’s a way of telling them the majority doesn’t actually agree with restrictive book banning,” one student explained to Cowboy State Daily. “It’s the job of the board to provide a quality education.”

It’s like someone wants to put people in a box and hide them from the world.

A New Haven, Connecticut student responding to bans on books like Flamer by Mike Curato

And in New Haven, Connecticut, over 100 high school students marched to protect the freedom to read. Students spoke openly about how books about race, gender, and sexuality helped them understand their history, their peers, and themselves. “It’s like someone wants to put people in a box and hide them from the world,” one student said.

Students have routinely pushed back against the idea that book bans protect them from complicated topics. “Trying to hide the kind of unpleasant truth from us, that doesn’t do any good,” said one student in Miami, Florida. “In fact, that’s harmful.”

Similar sentiments were echoed by middle school students in the Hempfield School District in Pennsylvania. They led a walkout over new guidelines for books and the potential for removing library books deemed sexually explicit or inappropriate. The students carried signs proclaiming, “You can censor books, but you can’t censor our voices.”

From Connecticut to Wyoming to Alaska and Florida, across the country students have led the charge in not only raising awareness but, in some cases, successfully restoring access to books. They have founded banned book clubs and worked with teachers to distribute books to other students in districts where they have been banned; started funds to purchase new books for districts impacted by bans; and created free community bookshelves throughout their towns.

Robust student resistance can be understood as a leader in, and microcosm of, a larger resistance network that also includes authors, parents, advocates, and lawmakers.

Trying to hide the kind of unpleasant truth from us, that doesn’t do any good. In fact, that’s harmful.

A Miami, Florida student responding to prohibitions on teaching about race and LGBTQ+ topics

In January 2024, several authors launched the nationwide Authors Against Book Bans to support the librarians, teachers, and communities across the country coping with the crisis. Parents, too, are organizing to protect students’ freedom to read, calling on school districts to cater to the full community rather than the voices of a few censors. Last fall, for example, a group of Texas parents formed the Texas Freedom to Read Project as a sister organization to the Florida Freedom to Read Project. Both organizations are led by parents who are leading and supporting local organizing efforts against book bans in their communities.

Larger national organizations have also done their part. Fight for the First, a new organizing platform developed by EveryLibrary, gives local groups tools to share petitions and information about book bans, legislation, and local actions. The platform operates alongside groups like the National Coalition Against Censorship and We Need Diverse Books and new initiatives like Unite Against Book Bans that push to keep diverse literature on the shelf.

The resistance has found its way to statehouses and courthouses too. California and Illinois have enacted “anti–book ban” legislation to protect students’ right to read, and Maryland, New Jersey, and Colorado have attempted to follow in their footsteps. Multiple lawsuits in Iowa, Texas, and Florida have struck wins in the fight for open shelves. A recent motion to dismiss PEN America’s own case in Escambia County, Florida, was rejected by the presiding judge, allowing it to move forward.

Together, this growing effort is demonstrating a diverse set of Americans from across the country believe in mounting a robust defense of the freedom to read. In standing firm in support of students’ rights to access a diversity of information, ideas, and viewpoints, this pushback is ensuring that school libraries can fulfill their missions to make knowledge available to all—regardless of the political whims of politicians and censorship-minded school board members.

Conclusion

The growing resistance to the book banning movement is a signal that today’s censorship efforts may be losing in the popular consciousness. But the crisis is not over. Every day, librarians are laid off and public libraries thrown into disarray, their already precarious funding further threatened. Educators are left unsure of their job security and physical safety, undermining their ability to do their jobs.

Book bans continue to target the very titles that are most vital to students: books exploring LGBTQ+ identities and gender identity; books about race and racism and featuring characters of color; and books about sexual violence. These books can be a lifeline, one that a vocal minority continues to try to suppress—effectively instituting a “heckler’s veto” over literature.

The freedom to read is fragile, and it is damaged with each book that is removed from the shelf. As the movement to ban books spreads further across the country, and as legislation that makes it easier to censor calcifies into law, it is more important than ever before to fight back to protect this necessary right to read. A broad coalition of students and advocates has heeded the call: even in the face of extreme state laws, hateful rhetoric, and an extraordinary number of bans, the fight for the freedom to read has never been stronger.

The message is clear: books aren’t harmful—censorship is.

Appendix

PEN America’s Methodology

This data snapshot and trend analysis reports bans and district cases where the initiating action for the ban occurred between July 1 and December 31, 2023. We track instances of books bans at the district level, meaning one case of a ban is when a book title is removed from access within a school district. PEN America records book bans through publicly available data on district or school websites, news sources, public records requests, and school board minutes.

The true magnitude of book banning in the 2023–24 school year is unquestionably much higher than the data presented here. PEN America’s researchers continue to discover books banned in the previous year; thus our reporting may not be comprehensive of all books removed from access during the six-month reporting period. Books are often removed silently and not reported publicly or validated through public records requests. For a full discussion of our methodology, see our Frequently Asked Questions.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Sabrina Baêta, program manager, Freedom to Read, and Sam LaFrance, manager of editorial projects, Free Expression and Education. The report was reviewed and edited by experts from the Freedom to Read Program—Kasey Meehan, program director; Tasslyn Magnusson, PhD, senior consultant; and Madison Markham, program assistant—as well as Jonathan Friedman, Sy Syms managing director, U.S. Free Expression Programs. Lisa Tolin provided editorial support, and Daniel Cruz and Nikki Gallant provided critical support for data collection and analysis. Ryan Howzell and James Tager supported the research review and organizational process, and Grey Nebel conducted a fact-check. Geraldine Baum, chief communications officer, oversaw production and release of the report. Rita Carlberg copyedited the report.

PEN America is grateful for support from the Endeavor Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, and the Long Ridge Foundation, which made this report possible. We also thank key partners in this work, including the Florida Freedom to Read Project, the Texas Freedom to Read Project, and Let Utah Read.

Finally, we extend our gratitude to the many authors, teachers, librarians, parents, students, and citizens who are fighting book bans, speaking out in their communities, and raising attention to these issues. We are proud to stand with you in defending the freedom to read.