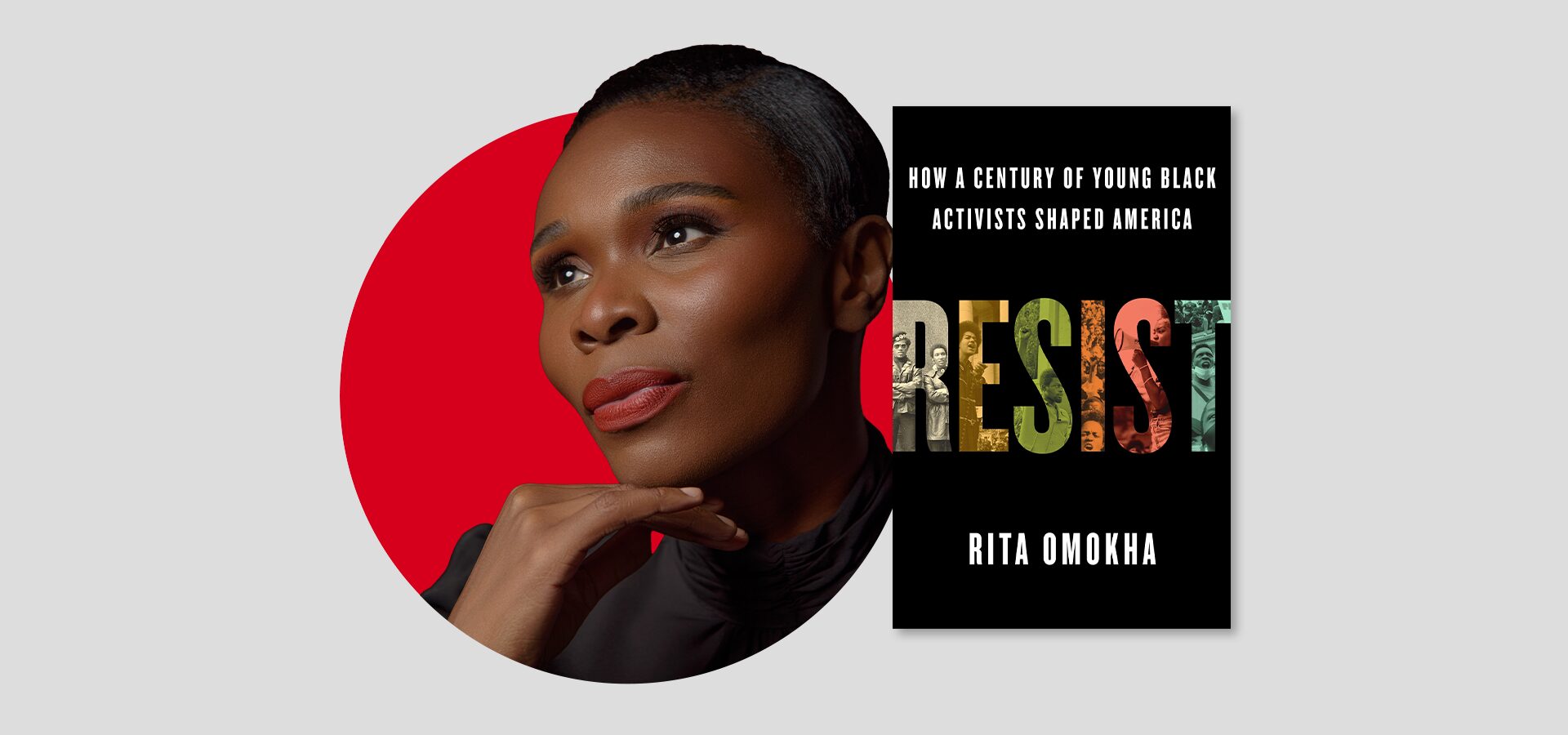

With verve and assiduity, Rita Omokha’s debut book, Resist: How a Century of Young Black Activists Shaped America (St. Martin’s Press, 2024) chronicles the inspiring stories of young Black activists in the United States who have been at the vanguard of social justice in the last century. From the early days of civil rights icon Ella Baker to the nationwide protests following George Floyd’s murder, Omokha’s trenchant account illustrates how, from generation to generation, young Black activists have been front and center in the quest to make the American experiment more inclusive and just.

In conversation with PEN America’s Government Affairs Liaison, Christian Omoruyi, for this week’s PEN Ten, Omokha discusses the impetus for writing Resist, provides insights into dimensions of young Black activism across decades, and reflects on the book’s impact on her Black identity. (Bookshop; Barnes & Noble)

Congratulations on your inaugural book! What compelled you to write about the past century of young Black activism now? How long have you been working on Resist?

It was happenstance. The idea began to form in 2020. With all that was happening—COVID, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery—I felt compelled to travel across the country to document the time, to speak to everyday people about how they were navigating that period. To have candid conversations about how they were contending with race relations.

Ultimately, I traveled to 30 states in 32 days, interviewing more than 120 people from all backgrounds in small towns and large cities—stopping in places such as Stuart, Nebraska; Kenosha, Wisconsin; LA; and the Navajo Nation.

One stop in particular stood out from the rest: Portland, Oregon.

There, I met with teenagers who were acutely aware of the plight before them. They had organized this enormous protest in remembrance of Patrick Kimmons, a Black man killed at the hands of police two years prior. At the same time, they were decrying the systemic injustices in America.

Witnessing it all was mesmerizing, not only because it was my first-ever protest but also because I was in awe of how these teens—barely 14 or 15—were moving, organizing, and galvanizing in such a dynamic yet methodical way.

When we came to a halt, I remember just looking out into the crowd—at all the hundreds of people—and thinking, “Wow, look at this.” And then it struck me. How did the teens know they could even do this? How did they know they could organize like this? And I think that line of questioning came from a place of being a perpetual outsider as an immigrant to this country. There are still moments in this country that I just stop, pause, and question—why is this done in this way? What unspoken rule(s) don’t I know about this very thing? How did this way of organizing even take shape? And what values or beliefs make this possible?

That line of questioning led me to Resist. I wanted to examine the origin story of protests and galvanization by young people in this country, specifically young people of color. I wanted to unpack the cost of the freedom we all revel in today as inheritors of this democracy—the same freedom that is now being threatened today. In their demonstration that day, I saw them actively resisting the status quo, striving to restore the spirit of American democracy, and rising against opposition.

In the end, I wanted to make history personal. That’s a lesson I walked away with after my 2020 trip and researching and writing this book: that in order to make history real in my life, there needed to be intentionality in interrogating the hows and whys of this American democracy. We’re still in that phase where, at every turn, this American experiment of democracy is being tested, and the likes of Donald Trump show us just how fragile it is.

You highlight the intergenerational tensions between Black youth activists and the older Black establishment both during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s and the early days of the Black Lives Matter movement in the 2010s. You understandably critique the paternalism of Black elders in both eras. Based on your reportage, given that many Black youth who were involved in activism in the 1960s now form the older generation of the contemporary Black establishment, what are the lessons young Black activists today can draw from their elders?

Young people often hold on to idealism, injecting new energy and ideas into the ongoing fight for parity, while the older generation tends to hold onto more traditional approaches, cautious of radical shifts that might destabilize hard-won progress. But that doesn’t mean the older generation’s experience isn’t valuable. In fact, there’s a lot today’s young can learn from our elders, even if there are disagreements.

First, many elders were once the youth shaking things up. They know what it’s like to be bubbling with intense vigor. They know what it’s like to face intense opposition—violent backlash, imprisonment, and even death threats—while continuing to press on. They figured out how to move from what if to even if. What if this happens? What if that happens? Instead, they said, “Even if this happens (at times, death), we keep moving forward.” That’s powerful.

And despite differing strategies and internal conflicts, they achieved landmark victories in the fight for civil rights. (For example, because of that movement, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was passed, ultimately paving the way for my mother’s entry to this country, leading to my being here. Isn’t it wild how easily we can take such strides for granted because they feel like obscurities wrapped in the vastness of history?) Their perseverance under such dire conditions and circumstances provides a roadmap for sustaining long-term movements, even when immediate outcomes seem distant.

Another thing that can be gleaned from our elders is strategy. They had to figure out how to navigate complex political landscapes, often finding ways to work within systems while still pushing for radical change. While the tactics may have been different, those strategic lessons—like how to build alliances, balance competing interests, and know when to compromise or hold firm—are still relevant today.

Lastly, it’s important to remember that there’s power in collaboration. While there will always be some level of tension between the generations, there’s also an opportunity to work together. Elders bring experience and wisdom, and youth bring fresh perspectives. By bridging that gap, we can build stronger, more effective movements.

When reflecting on the injustices faced by the Jena Six, you write that American exceptionalism is rooted in “oppressive beliefs poisoned by prejudice.” Your contention brought to mind a quote from Alexis de Tocqueville: “The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults.” Can your observation be reconciled with de Tocqueville’s? Why or why not?

There’s certainly a shared understanding of America’s imperfections. Our sentiments can coexist but reflect different aspects of America’s identity.

My contention stresses the historical and ongoing injustices that reveal the continued prejudice embedded within the system. These biases are a painful, blatant reminder that American exceptionalism has often been intertwined with systems of oppression.

De Tocqueville reflects a more optimistic view, suggesting that America can improve itself despite these faults. His perspective, though, comes from a foreign lens that isn’t as attuned to the deeply entrenched biases marginalized communities have confronted for generations. His optimism may even stem from a kind of privilege that allowed him to see the promise of America’s ideals without experiencing the daily reality of its injustices. And while I also have a foreign lens as a Nigerian-born naturalized citizen, most of my youth and adult years have been spent in America since I arrived as a child—so it’s fundamentally colored my experience. It’s given me a most personal vantage point, shaped by both the hopes of opportunity and the harsh realities of inequality.

This unique lived experience has led me to believe that the question of repair—of reconciliation—is nuanced. Because ultimately, that depends on America’s willingness to contend with and mend not just the symptoms but the root causes of injustice. Real restoration demands confronting the complex, systemic foundations that uphold inequality—not just making surface-level adjustments.

De Tocqueville’s faith in America’s capacity for self-correction is idealistic at best. Is it possible? Yes. But only if we—America—acknowledge the depth of the systemic oppression my observation points to. Have we seen any such intentional attempts at reconciliation and acknowledgment in recent years? Unequivocally, the answer is no.

Perhaps de Tocqueville and my perspectives can be reconciled if we see America’s greatness not as something inherent but as something that must be actively pursued through genuine reform and a commitment to addressing the roots of injustice. Because American identity is complex: It embodies both its foundational ideals of liberty and equality and the long history of prejudice that contradicts those ideals. America’s identity is constantly evolving, but achieving true “greatness” will require an intentional effort to reconcile these opposing forces.

My contention stresses the historical and ongoing injustices that reveal the continued prejudice embedded within the system. These biases are a painful, blatant reminder that American exceptionalism has often been intertwined with systems of oppression.

I appreciated how you internationalized your accounts of the Scottsboro Boys and Wilmington Ten by highlighting the global upwelling of solidarity their trials spawned. What was the most interesting fact you stumbled upon in your research about the global impact of these cases?

Overarchingly, one of the most striking findings was how the plight of Black Americans, particularly in the cases of the Scottsboro Nine and Wilmington Ten, resonated deeply with the struggles of those who identify as an-other elsewhere and those who have long been allies in the fight, globally.

When I delved into the global outcry surrounding their trials, both chapters reflected and underscored that very shared solidarity between the movements, showcasing that those struggles for justice bond us: I don’t have to know your specific story to understand the effects of oppression and resistance.

The global response to the Ten’s case, for instance, drew comparisons to South Africa’s own racial oppression—with anti-Apartheid young activists like Steve Biko and Barney Pityana (who were both awakened to the movement by the then-imprisoned Nelson Mandela) at the forefront in South Africa—as students in America recognized the chilling similarities in the brutal treatment of Black people in both regions.

This shared struggle against injustice created a powerful global alliance among activists, proving that shared experiences can bridge geographical divides.

You thoroughly chronicle the role social media has played in Black youth activism over the past decade, which has been in many ways catalytic and constructive. This said, the ubiquity and incentive structures of social media platforms also abet faux, performative activism. In your interviews with contemporary youth activists, did you encounter any frustration with the role social media platforms play in mobilizing their peers? What was the general opinion on performative activism via social platforms?

Absolutely. My conversations around social media’s dual impact on activism were a common topic of admiration and critique.

Many felt that platforms like X, Instagram, and TikTok have been invaluable for spreading awareness, building solidarity, and mobilizing one another at unprecedented speeds. They have become a cherished community for so many, especially young people. It enables activists to connect across regions, share real-time updates, and amplify causes that might otherwise be overlooked by mainstream media. I got the sense that social media has democratized activism for many young activists I spoke with, making it more accessible and empowering those who may not have traditional platforms for their voices.

However, there was notable frustration expressed around the prevalence of performative activism on these same platforms. Think about all the black squares companies (newsrooms and book publishers included) placed on their social pages following George Floyd’s death and the uprising that followed. Fast-forward to today. What tangible, meaningful changes can be measured? Data shows close to zilch.

Ultimately, the sentiment was that social media has been a double-edged sword. While opinions largely varied, the general view was that performative activism is a significant drawback of social media but one that can be navigated with critical awareness. However, that didn’t seem to dissuade them from using it as a way to be active in activism.

You foreground the advocacy of young Black women including Johnetta Elzie who have been at the vanguard of racial justice activism since the Obama presidency. Compared to previous generations, how are the Black women activists you interviewed combating gendered assumptions and patriarchal attitudes in their work today?

Today, these women are approaching the fight against racial injustice with a strong awareness of how such norms impact their work and the communities they represent. That’s the benefit of history as our teacher.

They have been able to build on the legacy of previous generations—of women who fought before them. They have adapted these lessons to new challenges, showing that honoring history can coexist with innovation. Holding on to such lessons, they have been able to confront gendered stereotypes by refusing to conform to expected soft roles and challenging the criticism they often face for being “too outspoken” or “too aggressive.” Now, they’re openly resisting such limiting narratives by proudly embracing their identities and refusing to be sidelined.

One distinction today is their emphasis on collective action rather than hierarchical leadership. This counters patriarchal structures, which often prioritize individual leadership over community-focused organizing. Another key difference today that enables that counter is their strategic use of digital platforms, as I outlined in Chapter 8, with how Elzie communicated what she saw on the frontlines of protesting and organizing following Michael Brown’s death. She leveraged social media to uplift her community, connect with a wider audience, and mobilize grassroots support.

Unlike many past movements that tended to be led by male figures, women leaders today insist on being visible in leadership roles and center their activism on intersectional issues—recognizing that the fight for racial justice is incomplete without addressing the interconnectedness of race, gender, class, and sexuality. They are addressing systemic inequalities and advocating for policies that benefit marginalized communities as a whole.

These women are approaching the fight against racial injustice with a strong awareness of how such norms impact their work and the communities they represent. That’s the benefit of history as our teacher.

As someone who has met bereaved mothers from the Mothers of the Movement, I was moved by how you humanized their experiences and rendered justice to their stories with a poignancy lacking in mainstream media narratives. What gives you hope about their activism?

Transparently, I don’t know if I can say I have hope at the moment. These mothers have thrown themselves on the frontlines time and again, and almost nothing can be shown for it. No recourse for most of them, no justice for many, and they’re left in cycle agony. They’re triggered each time another death by police happens.

So, if I’m being real, it’s hard to grasp any hope. I’ve been in a constant state of dismay. I wish I had some optimistic, forward-looking take on this, but I don’t right now—not against the recent presidential election outcome. Not against the rising over-criminalization of one subset of our nation’s population. Not against the basic erosion of civil liberties. Liberties that were fought for are now slowly being eradicated. So, I’m in a season of grieving what this nation once was to me—wide-eyed, looking upon its promise for all. It was a romanticized view, yes, and now, I wish I was less knowledgeable so I could have the hope you ask about.

But the reality is, it’s simply frustrating to think that countless more mothers—and surviving family members—continue to fight a battle that feels endless and disregarded by the system meant to protect and care for them. They march, organize, and speak out, putting everything on the line to demand accountability, yet the cycle persists. The system’s indifference, or even outright hostility, to their pain, just reinforces how broken it is. They’re not just asking for sympathy—they’re demanding that their children’s lives be valued, that their suffering not be ignored. And yet, it’s as if their voices are intentionally discounted.

In chapter 6, you aptly deem education “a prized portal to independence” and “agent of autonomy” for Black youth coming of age, which is why opponents of racial progress everywhere seek to bowdlerize or outright deny it. Amid a steep rise in educational censorship and book bans taking aim at Black history across the United States, how can Black youth activists counter this surge and advance the fight for educational equity?

They can draw on the powerful legacy of resistance and transformation in education. Take Brown v. Board of Education. It wasn’t just a landmark case about school integration but a testament to education as a battleground for equality and self-determination. Just as the youth activists of that era demanded an end to separate but equal, today’s youth face a different yet familiar struggle: combating erasure and selective truth-telling in schools.

When I delved into this in Chapter 4, I went into the story of Barbara Johns of Prince Edward County. Her fight is a prime example of youth-driven activism that laid the groundwork for the fight for educational equity, particularly in the face of oppressive systems that sought to deny Black students a quality education.

Her movement was so powerful that it ultimately became one of the five cases consolidated into Brown, underscoring that youth activism has historically been a catalyst for profound legal and social change. The fight was always about parity—which remains true even now.

Today, as we witness book bans and educational censorship targeting African American history, today’s activists are standing on the shoulders of Johns and other young leaders who refused to accept a second-class education. Like Johns, they recognize that the denial of truthful, inclusive education is a deliberate attempt to strip away empowerment. To counter this surge in censorship, today’s youth should take inspiration from Johns. They could (and many have) organize sit-ins, rallies, and educational workshops, reaffirming their right to a full, unfiltered history.

I don’t want to be glib about any of this and want to ensure I don’t discount the fact that they’re up against a calculated effort to whitewash history—a deliberate attempt to close off that prized portal. However, as history teaches us, change often begins when young people step up as torchbearers. Through coalitions, community organizing, and now social media campaigns, they can work to amplify their demands, exposing how censoring history undercuts democracy itself. (The contradiction is just too glaring.)

What prompted you to include your personal commentaries about the decades you chronicled at the end of each of the book’s chapters?

I do a lot of self-talk—I just talk myself through multiple things. I promise it’s not as bizarre as I just framed it. It actually helps me process what I’m feeling and keep myself grounded. Sometimes, just hearing my own thoughts out loud makes things feel more manageable like I’m guiding myself step-by-step through whatever’s in front of me. It’s a way of reminding myself that I can handle it, even when things feel overwhelming. I end up doing this or that thought experiment while in that state of intentional solitude.

So, when I began working on Resist, the first thing I thought through for weeks was how exactly am I going to tell 100 years of such history in a way that is digestible and accessible. Right? Because what’s the point of having all this research if it’s going to come across as dense or hard to follow? While researching Barbara Johns, the idea of structuring the book in that way came to me.

I had spent about a month reading up on her and that period. One evening, I naturally journaled about what I was feeling, generally, after another round of self-talk. As I did, I wrote about one scene that I ended up putting in the book where Johns goes on this walk in the woods behind her home after being fed up with her school district mistreating and neglecting her all-Black school. The white-only school kept getting all these upgrades while Johns and her classmates sat in tar-paper shacks. When it rained, it’d pour down on them. And so, on this fall day in 1950, she’s out in the woods, thinking about what she felt she could do to bring about change at her school. And I’m thinking, Wow, at such a young age, in such an oppressive time, she felt she could do something?

I don’t know why, but I just sat with that for a while. How did she know she could even do anything?

I journaled about her thinking pattern on about three separate occasions. Her life was one I really connected with: coming of age, trying to figure out why you exist in this big, big world. But she was coming up at a time when the system told her day in and day out that she didn’t matter. Yet she rose.

When I sat down to begin writing the book, I read back my journal entries about her. As I read them, I thought, Man, this perspective is raw. I wonder if readers could benefit from it.

It was almost like I was doing my self-talk, but with, well, everyone. It ended up serving as this important, propulsive yarn throughout—a way to guide readers through the different decades. It also made the writing thrilling. (It also made the self-talk moments a bit more complicated and emotional at times.)

Change often begins when young people step up as torchbearers. Through coalitions, community organizing, and now social media campaigns, they can work to amplify their demands, exposing how censoring history undercuts democracy itself.

You reflect on how your research for Resist has helped to clarify your claim to Blackness as someone who is not descended from African American slavery. As a fellow child of Nigerian immigrants, what do you hope Black Americans who are not descended from enslaved ancestors take away from your book?

I’ve been disheartened by the Black immigrant versus Black American narrative over the years. I navigated it for so long, coming up in the South Bronx and steering the complexities of belonging to both my Nigerian heritage and the larger Black American community.

As someone who America classifies as Black but is not directly descended from enslaved ancestors, I wanted to intentionally highlight that there is a shared sense of solidarity within the global African Diaspora that respects both commonalities and distinctions. For those of us who don’t have a lineage tied to American slavery, I hope this research underscores our place within the broader narrative of Black identity, reminding us to honor and contribute to its depth. That we’d understand, on a deep level, that without those who came before us in this country—those who were enslaved and suffered to pay for our freedom—we would not be possible in this country. And that is an indisputable fact.

Rita Omokha is an award-winning Nigerian American journalist. Her writing on politics, race, and vulnerable communities has been featured on CNN and in Cosmopolitan, The Daily Beast, Elle, Glamour, The Guardian, New York Magazine, Vanity Fair, The Washington Post, WIRED, and elsewhere. She’s an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, where she graduated at the top of the 2020 class, receiving some of the institution’s highest awards, including the Pulitzer Prize Traveling Fellowship. She lives in Manhattan.