Freedom to Write Index 2020

This report reflects PEN America’s 2020 Index findings. For our complete, up-to-date database, see the Writers at Risk Database.

Introduction

On April 3, 2020, as COVID-19 cases surged on multiple continents, prompting lockdowns and states of emergency and casting a global pall of anxiety and grief, renowned Indian author and winner of the Man Booker Prize Arundhati Roy wrote an essay entitled, “The Pandemic is a Portal.” In what was perhaps the first great piece of writing about the pandemic, Roy did what writers, more than any other figures in our society, are uniquely equipped to do. She shined an unflinching light on humanity, on the societies and structures we have built, and how they were failing us in our moment of need. She showed us not only what was new and novel about the pandemic, but what old, long-established, and deeply entrenched inequities it was rapidly exposing. She wrote primarily about India but told a story that was true of many countries around the world—of governments too consumed by politics to mount an efficient public health response, of a catastrophic lack of planning or preparedness, of overlapping crises, and of people left in fear and uncertainty. And yet, despite the grim images in the mirror she held up for us, she also offered hope. She placed our chaotic, anxiety-ridden moment in historical context, and showed us that this crisis held the potential for a moment of great transformation:

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.”1Arundhati Roy, “Arundhati Roy: ‘The pandemic is a portal,’” Financial Times, April 3, 2020, ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

Writers have played an essential role during the pandemic, analyzing and critiquing government responses, documenting personal experiences, and shocking us into recognition that we must not return blindly to patterns of the past. The protest movements that spanned the globe in 2020 calling for racial justice, the defense of democracy, and a reckoning with historical wrongs also made plain the essentiality of not reverting to a static “normality,” but purposefully moving forward to build a more just and equitable future. It is no coincidence that writers and artists played an essential role in many of those movements, nor is it surprising that they were targeted for it. Not only does Roy’s essay show us the potential of this historic moment of trauma and transformation, but it also demonstrates the power that writers have to help us to make sense of this time, and to envision what comes next.

For those with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, that power poses a threat. Political leaders the world over—in autocracies and fragile democracies alike—have used the pandemic and protest movements as an excuse to further constrain rights rather than expand them; they have wielded laws about disinformation as a means of silencing the truth; and they have specifically targeted those with the power to imagine and inspire. What lies on the other side of this portal is yet to be determined, but there is no question that the influential voices of writers are indispensable in helping us to find the path forward, and that the freedom to write has never been more essential to defend.

States of Emergency: The Pandemic, Protests, and the Persistent Assault on Global Free Expression

The climate for free expression globally continued to deteriorate in 2020, with existing challenges in authoritarian and more democratic political environments compounded by new threats. Most dramatically, the COVID-19 pandemic added unprecedented dimensions to existing crises for millions around the world and sparked new threats to freedom of expression. In the context of a global public health crisis, the ability to communicate freely and share and receive information quickly became a lifeline. Writers have helped expose truths and counter falsehoods in ways that have shaped the global public health response. At the same time, the emergency provided cover for crackdowns on human rights and expansions of government power over speech and expression. A proliferation of global protest movements during 2020 also represented a powerful unleashing of vocal public demands for change—and sparked a countervailing effort to restrict protest rights and detain those who raised their voices to demand freedom and equality. Writers and public intellectuals have played an essential role in narrating and shaping our perception of this singular moment, and in all too many cases, they have paid a price for doing so.

During 2020, at least 273 writers, academics, and public intellectuals in 35 countries—in all geographic regions around the world—were unjustly in prison or held in detention in connection with their writing, their work, or related activism.

During 2020, according to data collected for PEN America’s Freedom to Write Index, at least 273 writers, academics, and public intellectuals in 35 countries—in all geographic regions around the world—were in prison or unjustly held in detention in connection with their writing, their work, or related activism. This represents a sizable increase from the 238 individuals counted in the inaugural 2019 Freedom to Write Index. By holding these individuals behind bars, their governments are depriving them of their individual right to free speech, while also robbing the broader public of access to their innovative and influential voices of dissent, criticism, creativity, and conscience. The top three countries—China, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey—still accounted for a majority of cases, 50 percent, down from 59 percent in 2019. Meanwhile, numbers increased in Iran and Egypt, and expanded dramatically in Belarus, which accounted for zero cases in the 2019 Index, but now ranks as the fifth worst jailers of writers and intellectuals, with 18 documented cases (or 7 percent of the total), as a result of a brutal post-election crackdown on mass protests that has also targeted translators, artists, and other cultural figures.

Writers Imprisoned Globally: 2020

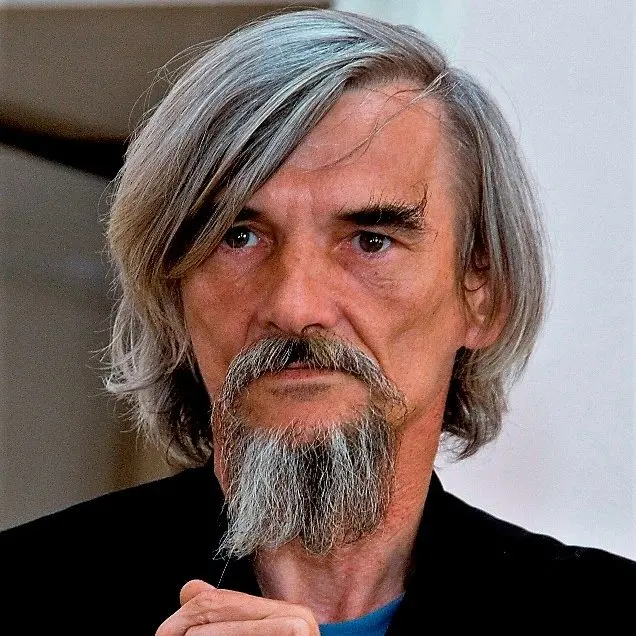

Yury Dmitriev

Russia

Status: Imprisoned

Russian historian Dmitriev was jailed in 2016 on retaliatory charges for his work uncovering the mass graves of thousands of victims of Stalin-era executions.

Photos by Medifond and Visem

While many writers included in the Index hold multiple professions and are, for example, both literary writers and poets, the most prevalent professions of those incarcerated are: literary writers (107), scholars (54), poets (57), singer/songwriters (30), publishers (13), editors (11), translators (8), and dramatists (3). Of these 273 individuals, 2 died while in custody, 3 died following their release, and 176—roughly two-thirds—remain in state custody at the time of this report’s publication.

The majority of those writers and intellectuals included in the 2020 count were initially imprisoned or detained prior to 2020, or had faced previous detention or imprisonment. Of the 273 in prison or detention during 2020, roughly 71 percent of them had also spent multiple days behind bars in 2019. This figure also includes 12 cases of individuals who were detained or imprisoned prior to 2020 but whose status only became publicly known during the past year. Such cases are common especially in environments where there is little transparency to the judicial process and limited press access; for example, in Xinjiang and Tibet in China. In many of these cases, detention is not confirmed until formal charges are made. The remaining roughly 29 percent of the 2020 Index comprises 79 writers and intellectuals, in 25 different countries, who were newly detained or imprisoned in 2020.

The largest number of new cases of writers and public intellectuals detained or imprisoned in 2020 came from Belarus, where the cultural community has played a leading role in the protests that followed the August 2020 presidential election, in which Alexander Lukashenka claimed victory despite election monitors concluding the election was “neither free nor fair,” and the European Union rejecting what it called the “falsified” results.2Liliya Yapparova, “The angry and the powerless: How the opposition protests in Belarus became a guerilla movement. Liliya Yapparova reports from Minsk,” Meduza, January 5, 2021, meduza.io/en/feature/2021/01/05/the-angry-and-the-powerless; Council of the European Union, “Belarus: Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union on the so-called ‘inauguration’ of Aleksandr Lukashenko,” press release, September 24, 2020, consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/09/24/belarus-declaration-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-european-union-on-the-so-called-inauguration-of-aleksandr-lukashenko/ Lukashenka’s regime has responded to the protests with a violent crackdown and widespread detentions, and has targeted influential cultural figures playing a role in the protests and broader movement to reject Lukashenka’s authoritarian rule. As a result, after having had no cases included in the 2019 Index, Belarus entered the top tier of the 2020 Index, ranking fifth in the world for detaining and imprisoning writers and intellectuals.

The remaining majority of these 79 new cases of writers and intellectuals have been detained or imprisoned during 2020 in countries that were within the top 10 jailers of this group in the previous Freedom to Write Index: China (12), Egypt (6), Vietnam (5), Iran (5), Saudi Arabia (3), India (3), and Turkey (2).3“Freedom to Write Index 2019,” PEN America, accessed March 15, 2021, pen.org/report/freedom-to-write-index-2019/ Individuals were also newly detained or imprisoned during 2020 in countries that held a smaller number overall, including Bangladesh (3), Thailand (3), Cambodia (2), Cuba (2), the Palestinian Territories (2), Sri Lanka (2), Israel (1), Jordan (1), Kazakhstan (1), Morocco (1), Oman (1), Pakistan (1), South Sudan (1), Sudan (1), Tajikistan (1), Uganda (1), and Venezuela (1).

Importantly, a number of these newly detained writers have also been threatened, harassed, or detained for their work in the past, with their 2020 detentions forming part of a larger pattern of ongoing governmental retaliation against them for their writing or expression over time. Writers who fall within this subset include Moroccan historian Maati Monjib, Chinese legal scholar Xu Zhangrun, Palestinian writer Abdullah Abu Sharkh, Iranian literary and arts critic Anisa Jafari-Mehr, and Indian professor of literature Hany Babu.

Many of the trends documented in the 2019 Freedom to Write Index persisted in 2020. National security remains the primary claim authorities use to justify detaining or imprisoning writers and public intellectuals: at least 55 percent of detentions were based on allegations of undermining national security or membership in a banned group. Arbitrary detentions—unaccompanied by formal charges—made up at least 20 percent of the cases, leaving the accused writers and intellectuals in a state of legal limbo, without recourse to challenge the claims against them. Cases of arbitrary detention are particularly common in Saudi Arabia, where at least 66 percent of writers and public intellectuals are held on unknown or undisclosed charges.

Charges related to organizing, assembly, and activism were used in at least 16 percent of cases against writers. Retaliatory criminal charges, defamation, and charges related to disinformation were levied against writers as well, though in fewer instances. At least 25 cases were identified of writers and public intellectuals detained for alleged disinformation crimes, including those related to spreading allegedly false news about COVID-19, demonstrating the troubling ways in which authorities have abused such laws to quash critics and quell divergent views. A relatively smaller percentage of cases were brought against writers for allegedly making threats against religious authority, producing obscene materials, or inciting violence. One of the most significant trends of 2020 has been the targeting of writers, commentators, and others who have spoken out in criticism of their governments’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic; these cases were often brought on the grounds of national security, public order, or prohibitions against disinformation.

Governments of countries in the Asia-Pacific region continued to jail the most writers and intellectuals for their writing or expression. In total, 121—or nearly half of the global count—were jailed in Asia-Pacific, with the vast majority of those, 81, held in China. Significant numbers of writers were also held in Vietnam (11), India (9), and Myanmar (8). Countries in the Middle East and North Africa have also jailed significant numbers of writers and intellectuals, including Saudi Arabia (32), Iran (19), and Egypt (14). Countries in this region contributed to almost a third of the global count of imprisoned and detained writers, at least 81 individuals, in 2020.

Detentions and imprisonments of writers and intellectuals in Europe and Central Asia occurred largely in two countries: Turkey and Belarus. Turkey maintains its position as the jailer of the third-highest number of writers and public intellectuals worldwide, having held 25 of the 50 prisoners and detainees in Europe and Central Asia during 2020. The crackdown against those protesting Belarus’s stolen presidential election led to a startling number of writers and cultural figures being detained or imprisoned: while Belarus did not jail any writers in 2019, in 2020 the number jumped to at least 18 that can be documented—the actual number is likely higher. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa contributed to roughly 5 percent of the 2020 Index, representing 14 writers and public intellectuals detained or imprisoned. Two countries in the Americas contributed to just three percent of the 2020 Index, with six writers detained or imprisoned in Cuba and one in Venezuela.

Tragically, four writers who were detained during 2020 died in circumstances that appear related to their detentions: Saudi columnist Saleh Al-Shehi died from possible COVID-19 complications on June 19, 2020, after being released from prison and then spending three weeks on a ventilator;4“Saudi writer dies from COVID-19 shortly after release from prison,” Middle East Monitor, July 20, 2020, middleeastmonitor.com/20200720-saudi-writer-dies-from-covid-19-shortly-after-release-from-prison/ Uyghur poet and editor Haji Mirzahid Kerimi died in custody on January 9, 2021 while imprisoned for publishing “problematic” books;5Shohret Hoshur, “Prominent Uyghur Poet and Author Confirmed to Have Died While Imprisoned,” Radio Free Asia, January 25, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/poet-01252021133515.html Bangladeshi writer Mushtaq Ahmed died in a prison hospital on February 25, 2021, after nearly 11 months in detention, and after being denied bail six separate times;6“Bangladesh: UN rights chief urges transparent probe into writer’s death, review of law under which he was charged,” UN News, March 1, 2021, news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1086002 and Egyptian writer Amin El-Mahdy died on October 11, 2020, 11 days after being released from detention.7“Egyptian writer and Sisi critic Amin El-Mahdy dies days after release from jail,” Middle East Eye, October, 12, 2020, middleeasteye.net/news/egypt-sisi-critic-amin-mahdy-dies The jailing of writers and others unjustly detained or imprisoned amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic represents a harrowing—and life threatening—nexus between these concurrent crises of global public health and free expression in retreat.

In this report, PEN America will provide an in-depth analysis of the countries that detain and imprison the largest numbers of writers and intellectuals and explore the impact of the pandemic on the freedom to write; the role of these individuals in protest movements; and the continued threats to writers and intellectuals working in languages subject to political repression.

About the Freedom to Write Index

The 2020 Freedom to Write Index provides a count of the writers, academics, and public intellectuals who were held in prison or detention during 2020 in relation to their writing or for otherwise exercising their freedom of expression. For the past century, PEN America and the global PEN network have defended the rights of writers and intellectuals to express themselves freely, and advocated on behalf of those who have faced threats as a result of their writing or other forms of expression. The criteria for inclusion in the Freedom to Write Index thus adhere closely to PEN International’s standards for selection for their annual Case List.

The Index is a count of individuals who primarily write literature, poetry, or other creative writing; essays or other nonfiction or academic writing; or online commentary. The Index includes journalists only in cases where they also fall into one of the former categories, or are opinion writers or columnists. To be included in the count, individuals must have spent at least 48 hours behind bars in a single instance of detention between January 1 and December 31, 2020.

For the purposes of the Index and the status designations used to classify cases, imprisonment is considered to be when an individual is serving a sentence following a conviction, while detention accounts for individuals held in custody pending charges, or those who have been charged and are being held prior to conviction. Writers are, of course, also subject to other types of threats, including censorship, harassment, legal charges without detention, or physical attacks, and these are also analyzed to a lesser degree in this report.

PEN America works closely with the PEN International Secretariat and Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC), as well as the other members of the global PEN network. The Index and this report draw significantly from PEN International’s Case Lists, which in turn reflect input from PEN Centers around the world. The cases included in the Index are also based on PEN America’s own internal case list, the Writers at Risk Database, and PEN America’s Artists at Risk Connection (ARC) case list. Additionally, PEN America draws from press reports; reports from the families, lawyers, and colleagues of those in prison; and data from other international human rights, press freedom, academic freedom, and free expression organizations. The methodology behind the Index is explained in greater detail here.

The annual Freedom to Write Index has become an essential component of PEN America’s long-standing Writers at Risk Program, which encompasses support for and advocacy on behalf of writers under threat around the world. Another flagship component of PEN America’s year-round advocacy is the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, given annually to an imprisoned writer targeted for exercising their freedom of expression. Of the 48 jailed writers who have received the Freedom to Write Award from 1987 to 2020, 44 have been released due in part to the global attention and pressure the award generates. PEN America also publishes the Writers at Risk Database, a searchable catalog of the writers, journalists, artists, academics, and public intellectuals under threat around the world, including those counted in the 2019 Index and 2020 Index. This database offers researchers, rights advocates, and the public a wealth of actionable evidence of ongoing global threats to free expression.

The Pandemic and the Freedom to Write

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a world-changing event, affecting everyday life for billions. The pandemic has also deeply impacted the freedom to write, and the lives of many of the writers and public intellectuals who comprise PEN America’s case list. In many countries, the pandemic has caused not only a public health crisis, but has also caused or exacerbated crises of human rights and democracy.

Governments around the world have used the pandemic as an opportunity to further police people’s speech. The International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) has identified 52 examples of countries introducing new laws or policies—or amending existing ones—in response to the pandemic that criminalize disinformation or otherwise limit free expression.8COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker, International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL), and European Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ECNL) [hereinafter “ICNL COVID Tracker”] icnl.org/covid19tracker/?location=&issue=4,9&date=&type=1,2,3,4 They have documented another 40 examples of practical crackdowns or constraints on expression.9ICNL COVID Tracker. Perhaps most widespread is the introduction of new laws, regulations, or other policies criminalizing “false information” or “rumors” about the pandemic.10E.g., Arab News, “‘As dangerous as the virus’: Middle East cracks down on COVID-19 rumor mongers,” Arab News, March 30, 2020, arabnews.com/node/1649286/middle-east

In Saudi Arabia, at least one individual has been prosecuted, facing a maximum sentence of five years, under Article 6 of the Saudi Anti-Cyber Crimes Law for “producing COVID-19 rumors and news from unknown sources that affect public order.”11Saudi Gazette report, “Saudi Arabia to prosecute rumor monger,” Saudi Gazette, March 19, 2020, saudigazette.com.sa/article/591052/SAUDI-ARABIA/Saudi-Arabia-to-prosecute-rumor-monger In Indonesia, police have arrested and charged several people for allegedly defaming the president by criticizing his COVID-19 policies, a criminal charge that can carry up to 18 months’ imprisonment.12ICNL COVID Tracker – Indonesia; ICJR Staff, “Enforcing Article on the Defamation of the President, Police sets their face against Constitutional Court’s Decision,” April 8, 2020, icjr.or.id/enforcing-article-on-the-defamation-of-the-president-police-sets-their-face-against-constitutional-courts-decision/ The Algerian government amended its penal code in April 2020 to provide for new penalties for the “dissemination of false information,” with harsher penalties during a public health lockdown or “catastrophe.” Under these new provisions, those arrested for “false information” about COVID-19 face up to five years’ imprisonment.13ICNL COVID Tracker – Algeria. In Tanzania, new ministerial regulations released in July 2020 prohibit citizens sharing COVID-19 information “without the approval of the respective authorities,” at the risk of one-year imprisonment.14ICNL COVID Tracker – Tanzania. Uzbekistan amended its criminal statutes in March 2020 to provide for up to three years’ imprisonment for the online or media distribution of “false” information about quarantine or infectious diseases.15ICNL COVID Tracker – Uzbekistan. Also in March, Bolivia’s president promulgated a decree that included the imposition of criminal charges for those who “misinform or generate uncertainty among the population,” with a penalty of up to 10 years’ imprisonment.16ICNL COVID Tracker – Bolivia. Such laws pose an obvious threat to freedom of expression, granting officials broad new powers they can wield against writers, bloggers, journalists, dissidents, or critics of any kind. Others have used the virus as a justification to dramatically limit press freedom, such as Iran, where the government invoked the virus when attempting to implement a wholesale ban on print media in April of 2020.17Radio Farda, “Iran Journalists Protest Coronavirus Taskforce Ban On Print Media,” Radio Farda, March 31, 2020, en.radiofarda.com/a/iran-journalists-protest-coronavirus-taskforce-ban-on-print-media-/30519547.html

During 2020, governments detained and imprisoned writers and public intellectuals who criticized their response to the pandemic on the grounds of national security, public order, or prohibitions against disinformation.

Some of those who have raised their voices to criticize their governments’ handling of the pandemic have found themselves targeted or imprisoned as a result. In China, for example, the Wuhan doctor who first sounded the alarm over the coronavirus before succumbing to it himself, Dr. Li Wenliang, was harassed by police for “spreading rumors” in the earliest days of the epidemic, and Chinese writers, public intellectuals, and everyday citizens have since been targeted for either sharing uncensored information or criticizing the government’s response to the virus.18Alice Su, “A doctor was arrested for warning China about the coronavirus. Then he died of it,” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 2020, latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-02-06/coronavirus-china-xi-li-wenliang Poet Zhang Wenfang, was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for her online poem about the coronavirus that included vignettes of people’s experiences, with lines such as “The one who died while sitting up, whose family cradled their head as they waited for the hearse/The one who starved to death in their home during quarantine.”19Joseph Brouwer, “TRANSLATION: WEIBO USER SENTENCED TO SIX MONTHS OVER WUHAN POEM,” China Digital Times, February 24, 2021, chinadigitaltimes.net/2021/02/translation-weibo-user-sentenced-to-six-months-over-wuhan-poem/ After legal scholar Xu Zhangrun wrote an essay “Viral Alarm” criticizing the government’s repressive response to COVID, authorities placed him under house arrest, then subsequently detained him for seven days on retaliatory charges that he had solicited a sex worker in 2018.20Chris Buckley, “Seized by the Police, an Outspoken Chinese Professor Sees Fears Come True,” The New York Times, July 6, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/07/06/world/asia/china-detains-xu-zhangrun-critic.html

In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his political allies implied that physician and columnist Şebnem Korur Fincancı was an “enemy of Turkey,”21BIA News Desk, “Erdoğan calls Turkish Medical Association Chair ‘a terrorist’, hints at new law,” Bianet, October 14, 2020, bianet.org/english/politics/232726-erdogan-calls-turkish-medical-association-chair-a-terrorist-hints-at-new-law# after the Turkish Medical Association (TTB), an organization that she chairs, criticized the Turkish government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.22BIA News Desk, “Turkish Medical Association: We stand by our words, we are on our duty,” Bianet, September 17, 2020, bianet.org/english/politics/231035-turkish-medical-association-we-stand-by-our-words-we-are-on-our-duty In Bangladesh, cartoonist Ahmed Kabir Kishore and writer Mushtaq Ahmed were among a group of 11 people arrested on May 6, 2020, for criticizing the government’s response to the pandemic. Mushtaq Ahmed died in prison in February 2021, while Kishore remains in prison where he has reportedly been tortured and is in failing health.23Julfikar Ali Manik and Mujib Mashal, “Bangladeshi Writer Detained Over Social Media Posts, Dies in Jail,” The New York Times, February 26, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/02/26/world/asia/bangladesh-mushtaq-ahmed-dead.html In Kazakhstan, blogger Aigul Otepova was placed under house arrest and later forced into a psychiatric clinic after criticizing her government’s response to the virus on Facebook.24RFE/RL’s Kazakh Service, “Kazakh Blogger Critical of Government Forcibly Admitted to Psychiatric Clinic,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, November 23, 2020, rferl.org/a/kazakh-blogger-critical-of-government-forcibly-admitted-to-psychiatric-clinic/30964357.html Government figures the world over have not hesitated to respond to public criticism or even illustrations of the severity of the pandemic by punishing the messenger.

As the coronavirus has grabbed the world’s attention, it has given additional cover to autocrats to push repressive agendas, secure in the knowledge that the pandemic would depress popular turnout at protests and distract the international community from forcefully responding. The Chinese government appeared to seize this opportunity in June of 2020, imposing a draconian National Security Law that essentially strips Hong Kong’s 7.5 million people of the civic and political rights they had enjoyed under the “One Country, Two Systems” framework—including in the realm of academic freedom, freedom of expression, and press freedom.25“Hong Kong security law: What is it and is it worrying?” BBC News, June 30, 2020, bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-52765838 Just the year before, public outcry from both Hong Kong residents and the international community convinced the government to pull back from a lesser far-reaching bill, one whose principal effect would have been to allow people in Hong Kong to be extradited to mainland China, rather than applying the mainland’s draconian restrictions on all of Hong Kong. The fact that Beijing was able to impose a far more repressive law on Hong Kong, only a year later, indicates the extent to which the coronavirus has enabled authorities to take such repressive measures.

And the COVID-19 pandemic has also provided a convenient pretext for authorities to harass, detain, and arrest dissenters more broadly. In Uganda, novelist and journalist Kakwenza Rukirabashaija was detained and tortured in April, under charges purportedly related to COVID but which appear to have been motivated by authorities’ displeasure over his writing.26“Day of the Imprisoned Writer 2020: Take Action for Kakwenza Rukirabashaija,” PEN International, November 9, 2020, pen-international.org/news/day-of-the-imprisoned-writer-2020-take-action-for-kakwenza-rukirabashaija#:~:text=On%2013%20April%202020%2C%20Uganda,had%20been%20subjected%20to%20torture In China, police officers used the pretext of a “coronavirus prevention check” to find and arrest the essayist and activist Xu Zhiyong at his lawyer’s home, and to place poet Li Bifeng into “enforced quarantine” as a form of detention.27Helen Davidson, “Hong Kong arrests and Taiwan flybys: China advances its interests during Covid-19 crisis,” The Guardian, April 25, 2020, theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/26/hong-kong-arrests-and-taiwan-flybys-chinas-advances-its-interests-during-covid-19-crisis; Guo Rui, “Chinese police detain fugitive rights activist Xu Zhiyong during ‘coronavirus check,’” South China Morning Post, February 17, 2020, scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3051000/chinese-police-detain-fugitive-rights-activist-xu-zhiyong In Cuba, police invoked a coronavirus-related “health code violation” in November as a pretext to raid the headquarters of the artistic San Isidro Movement, arresting more than a dozen members of the movement.28“Cuban police raid HQ of dissident San Isidro Movement,” BBC News, November 27, 2020, bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-55098876

Increased Urgency: Conditions of Imprisoned Writers during the Pandemic

Prisons and jails, in particular, have been severely impacted by COVID-19 and its profound and rippling social and economic effects. Prisons and other sites of detention around the world are likely to be overcrowded, poorly maintained, unhygienic, and lacking adequate medical care and equipment. These conditions, often combined with malign neglect from authorities, have made prisons breeding grounds for the virus. Human rights advocates, public health professionals, and UN officials have repeatedly warned that prisoners face a disproportionate impact from COVID-19.29Miriam Berger, “Prisons are covid hot spots. But few countries are prioritizing vaccines for inmates,” The Washington Post, January 15, 2021, washingtonpost.com/world/2021/01/14/global-coronavirus-vaccines-prisons/; “Impact of COVID-19 ‘heavily felt’ by prisoners globally: UN expert,” UN News, March 9, 2021, news.un.org/en/story/2021/03/1086802; “Prisoners forgotten in COVID-19 pandemic, as crisis grows in detention facilities,” Amnesty International, March 18, 2021, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/03/prisoners-forgotten-in-covid-19-pandemic-as-crisis-grows-in-detention-facilities/; see also https://covidprisonproject.com/additional-resources/global-outbreaks/ In the United States, for example, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) found that by July 2020, the COVID death rate for those incarcerated in the United States was more than five times higher than the average U.S. death rate.30Brendan Saloner, Kalind Parish, Julie A. Ward, Grace DiLaura, and Sharon Dolovich, “COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Federal and State Prisons,” The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) 324, no. 6 (2020): 602–603, doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.12528 In recognition of this reality, early in the pandemic, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet directly called on governments “now more than ever” to “release every person detained without sufficient legal basis, including political prisoners and others detained simply for expressing critical or dissenting views.”31Michelle Bachelet, “Urgent action needed to prevent COVID-19 ‘rampaging through places of detention,’” UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet calls on governments to take urgent action to protect the health and safety of people in detention and other closed facilities, Geneva, March 25, 2020, transcript, ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25745&LangID=E

This virus not only knocks down old men like myself but also all kinds of aged concepts, beliefs and ideas. We are painfully crossing the threshold of a new world and, even more important, a new kind of human being.

Ahmet Altan, “I’m watching the coronavirus unfold from a Turkish prison. Here’s why I’m hopeful.”

This is a matter of serious moral concern, warranting global attention and action, and its impacts have not been limited to imprisoned writers and intellectuals but to all those imprisoned or detained.32PEN America’s Prison & Justice Writing Program examines and shines a light on these issues in the U.S.; read more at: pen.org/prison-writing/. See also PEN America’s April 2020 statement on the use, availability, and cost of e-readers in American prisons during the pandemic, at pen.org/press-release/prison-e-readers-and-tablets-should-be-free-during-coronavirus-outbreak/ In this context, we focus on the cases of writers, public intellectuals, and others within the scope of the Index who face an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 in prison, and the subsequent increased urgency of ensuring their freedom. This is especially the case for those who are older, in ill-health, or in other high-risk categories.

Despite these risks and calls for governments to free political prisoners, many, including writers and intellectuals, have remained or been newly placed in state custody during the pandemic, while governments have simultaneously downplayed the risks and attacked those who have attempted to draw attention to them. In March 2020, the family and supporters of Egyptian imprisoned blogger and activist Alaa Abd El Fattah staged a protest in front of the government’s cabinet building to bring attention to the acute risks that those held in prison face during the pandemic.33Louisa Loveluck and Sudarsan Raghavan, “How the coronavirus is igniting riots, releases and crackdowns in world’s prisons,” The Washington Post, March 26, 2020, washingtonpost.com/world/how-coronavirus-is-igniting-riots-releases-and-crackdowns-in-the-worlds-prisons/2020/03/25/6ca94494-6aba-11ea-b199-3a9799c54512_story.html;

Emma Graham-Harrison, “Egypt arrests activists including Ahdaf Soueif over coronavirus protest,” The Guardian, March 18, 2020, theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/18/egypt-arrests-activists-calling-prisoners-release-coronavirus-ahdaf-soueif; PEN America, “Egyptian Writer Detained for Protesting Prison Conditions That Could Worsen COVID-19 Spread,” press release, March 18, 2020, pen.org/press-release/egyptian-writer-detained-for-protesting-prison-conditions-that-could-worsen-covid-19-spread/ Abd El Fattah’s family held a placard that read, “Underestimating coronavirus in prisons puts the lives of inmates, police officers, conscripts and all who work in prisons and their families in danger. Release the prisoners.”34Loveluck and Raghavan, “How the coronavirus is igniting riots.” In response, the protesters—including Abd El Fattah’s mother, academic Leila Soueif; author Ahdaf Soueif; activist Mona Seif; and academic Rabab El-Mahdi—were forced to spend one night in jail before being released on bail.35Loveluck and Raghavan, “How the coronavirus is igniting riots;” PEN America, “Egyptian Writer Detained for Protesting Prison Conditions That Could Worsen COVID-19 Spread,” press release, March 18, 2020. They were charged with inciting a protest and disseminating false news, and blogger Abd El Fattah remains in pretrial detention.36Loveluck and Raghavan, “How the coronavirus is igniting riots.” In protest of the unjust living conditions facing prisoners in Iran’s Evin prison, writer and human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh went on a 46-day hunger strike from August through September 2020.37“COVID-19 Fear in Iran’s Prisons: Iran Must Do More to Protect Prisoners, Summer 2020 Update,” Abdorrahman Boroumand Center, September 2, 2020, iranrights.org/library/document/3764 Sotoudeh ended her weeks-long hunger strike after spending five days hospitalized in the cardiac care unit of Taleghani Hospital.38“Jailed Iran human rights lawyer hospitalised after hunger strike,” Al Jazeera, September 20, 2020, aljazeera.com/news/2020/9/20/jailed-iran-human-rights-lawyer-hospitalised-after-hunger-strike After she was temporarily released on medical furlough in November and reunited with her family, Sotoudeh tested positive for COVID-19.39Joseph Hincks, “’It’s Like We’re Hanging in the Air.’ Iranian Activist Nasrin Sotoudeh’s Husband on Her Temporary Release From Prison,” Time, November 20, 2020, time.com/5914225/nasrin-sotoudeh-iran-covid-19/;

“Iran lawyer tests positive for Covid-19 after release from jail,” France 24, November 10, 2020, france24.com/en/live-news/20201110-iran-lawyer-tests-positive-for-covid-19-after-release-from-jail Against the advice of medical professionals, officials ordered Sotoudeh’s return to prison the following month.40Maziar Motamedi, “Nasrin Sotoudeh: Iran human rights lawyer ordered back to jail,” Al Jazeera, December 2, 2020, aljazeera.com/news/2020/12/2/nasrin-sotoudeh-iranian-human-rights-lawyer-to-go-back-to-jail

In Belarus, the mass detentions that accompanied the public protests after the August 2020 election put many at additional and unnecessary risk of contracting COVID for their free expression and dissenting views.41Associated Press, “Virus Besets Belarus Prisons Filled With President’s Critics,” Voice of America, December 26, 2020, voanews.com/covid-19-pandemic/virus-besets-belarus-prisons-filled-presidents-critics In an interim report by the International Committee for the Investigation of Torture on Belarus, analysts argued that overcrowding, medical neglect, and non-isolation for COVID-positive individuals in Belarusian prisons was a deliberate strategy of abuse and torture.42PEN America, “PEN America Demands Belarus Drop Charges Against Olga Shparaga,” press release, October 16, 2020, pen.org/press-release/pen-america-demands-belarus-drop-charges-against-olga-shparaga/ In October 2020, writer and philosopher Olga Shparaga served a 15-day administrative detention at Zhodzina prison in relation to her role in the protests against Alexander Lukashenka, who has routinely downplayed the severity of COVID-19.43Yauhenia Stepus, “Belarus: Authorities Accused of Weaponising Covid-19 Against Protesters,” Institute for War and Peace Reporting, March 15, 2021 iwpr.net/global-voices/belarus-authorities-accused-weaponising-covid-19-against-protesters; Mary Ilyushina and Nathan Hodge, “Post-Soviet strongmen prescribe vodka, hockey and folk medicine against coronavirus,” CNN, March 31, 2020, edition.cnn.com/2020/03/30/europe/soviet-strongmen-coronavirus-intl/index.html Detained at Zhodzina prison, Shparaga shared a cell with eight people—in addition to the constant transfers of people detained amid the protests.44Stepus, “Belarus: Authorities Accused of Weaponising Covid-19 Against Protesters.” Following her release, Shparaga and five other people she was detained alongside tested positive for COVID-19.45Stepus, “Belarus: Authorities Accused of Weaponising Covid-19 Against Protesters.”

Life does not exist in Qarchak Prison of Varamin, the largest women’s prison in the Middle East. And this is what could be said in a nutshell. Here you can see the depth of the catastrophe created by those who hold the positions of power… This is a full reflection of our society under an authoritarian rule.

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, September 7, 2020 letter from Qarchak prison

In India, where the New Delhi–based National Campaign Against Torture has cited a direct correlation between overcrowding in prisons and positive cases of COVID-19,46HT Correspondent, “‘One-fourth jails in India report Covid-19 cases, many ‘highly’ congested’: Report,” Hindustan Times, September 16, 2020, hindustantimes.com/india-news/one-fourth-jails-in-india-report-covid-19-cases-many-highly-congested-report/story-Fb3z8MvZEtHIvXQBOYFtZK.html writer and human rights activist Gautam Navlakha was transferred in May 2020 from Tihar Jail in Delhi to a school in Maharashtra as a result of overcrowding, and described the conditions in the school as “deplorable.”47Scroll Staff, “‘350 inmates in six rooms’: Activist Gautam Navlakha kept in deplorable conditions, says partner,” Scroll.in, June 22, 2020, scroll.in/latest/965327/350-inmates-in-six-rooms-no-fresh-air-activist-gautam-navlakha-details-temporary-jail-condition Navlakha reported that, with 350 inmates crowded into six classrooms, he had to share a room with 35 other inmates and few restrooms and bathing spaces were available.48Scroll Staff, “‘350 inmates in six rooms.’” Octogenarian poet P. Varavara Rao contracted COVID-19 in July 2020 while detained and was reportedly initially cared for by co-accused academics Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira due to prison authorities’ grave neglect of his health.49Shruti Ganapatye, “Varavara Rao denied medical care: Family,” Mumbai Mirror, October 10, 2020, mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/coronavirus/news/varavara-rao-denied-medical-care-family/articleshow/78584481.cms After his diagnosis, Rao was transferred to three different hospitals in a single week, where his existing ailments and medical conditions worsened.50The Wire Staff, “Varavara Rao’s Continued Custody Amounts to Inhuman Treatment, Says Wife in SC Petition,” The Wire, October 16, 2020, thewire.in/law/varavara-rao-bail-petition-supreme-court-elgar-parishad-case-bhima-koregaon;

K A Y Dodhiya, “Varavara Rao fell from bed, unable to do anything on his own; allow us to help: Family to state,” Hindustan Times, July 21, 2020, hindustantimes.com/mumbai-news/give-us-updates-on-health-allow-kin-to-help-him-varavara-rao-s-family-to-state/story-a2Mv5dYQTma8tokaPVQVeK.html;

Sukanya Shantha, “Varavara Rao Tests Positive for COVID-19, Moved to St. George Hospital,” The Wire, July 16, 2020, thewire.in/rights/varavara-rao-covid-19-positive-st-george-hospital

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), where multiple detention centers faced outbreaks of COVID-19,51Human Rights Watch, “UAE: Reported Covid-19 Prison Outbreaks,” news release, June 10, 2020, hrw.org/news/2020/06/10/uae-reported-covid-19-prison-outbreaks the lengthy detention of writers including economist Nasser bin Ghaith, lawyer Mohammed Al-Roken, and poet Ahmed Mansoor during 2020 have raised serious concern, particularly as reports confirmed inhumane conditions of imprisonment.52Reuters Staff, “UN rights expert urges UAE to free jailed activists,” Reuters, February 10, 2021, reuters.com/article/emirates-rights-int/un-rights-expert-urges-uae-to-free-jailed-activists-idUSKBN2AA1U1; “Ailing Economist Confined in Jail in UAE Threatened to Contract COVID-19,” Committee of Concerned Scientists, August 3, 2020, concernedscientists.org/2020/08/ailing-economist-confined-in-jail-in-uae-threatened-to-contract-covid-19/ In Egypt, which detained the sixth highest number of writers and public intellectuals around the world, authorities at Tora prison, where blogger Abd El Fattah is held, reportedly denied coronavirus tests to detainees in June 2020 despite the reported spread of COVID-19 in multiple cell blocks.53“Egypt detainees report covid-type symptoms in 3rd cell block as virus spreads,” Middle East Monitor, June 5, 2020, middleeastmonitor.com/20200605-egypt-detainees-report-covid-type-symptoms-in-3rd-cell-block-as-virus-spreads In July 2020, when then-detained Turkish columnist Murat Ağırel reported severe tooth pain, he was taken to the prison hospital room and reportedly detained for five hours with COVID-19 positive patients.54BIA News Desk, “Jailed columnist Murat Ağırel: It is torture, I will not consent to this,” Bianet, July 14, 2020, m.bianet.org/english/human-rights/227411-jailed-columnist-murat-agirel-it-is-torture-i-will-not-consent-to-this In Iran, journalist and human rights activist Narges Mohammadi also displayed COVID-19 symptoms over the summer while imprisoned. Mohammadi, who suffers from an underlying health condition, wrote a public letter from Zanjan prison stating that she was showing symptoms of COVID-19, while one of her cellmates had tested positive.55UN experts, “Iran: UN experts call for the urgent release from prison of human rights defender with COVID-19 symptoms,” The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Media Release, July 22, 2020, ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26118&LangID=E After repeated requests, prison authorities only tested Mohammadi—who tested positive for COVID-19—when her family made a direct appeal to the Zanjan prosecutor’s office, the results of which authorities withheld from Mohammadi.56PEN America, “Iran Must Release Activist Suspected of Having Coronavirus,” press release, July 16, 2020, pen.org/press-release/iran-must-release-activist-suspected-of-having-coronavirus/ Mohammadi recovered from the virus and was released from prison in October 2020 after she had finished serving her sentence.57Miriam Berger, “Leading Iranian human rights advocate freed from prison amid fear of contracting coronavirus behind bars,” The Washington Post, October 9, 2020, washingtonpost.com/world/2020/10/08/narges-mohammadi-released-from-prison-iran-coronavirus-human-rights-death-penalty/

Writers and public intellectuals facing charges relating to national security—55 percent of the 2020 Index—typically did not qualify for COVID-related conditional releases.

COVID-19-Related Releases and Their Limitations

In some cases, governments did agree to release prisoners in an effort to suppress the spread of COVID-19, although very few writers or intellectuals were freed unconditionally on health-related grounds. Specifically, imprisoned writers facing charges relating to national security—the most common category of charge used against this group—typically did not qualify for COVID-related conditional releases.

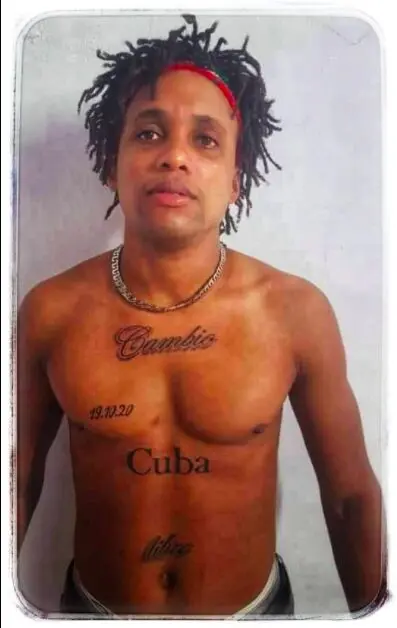

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee

Iran

Status: Imprisoned

While in prison during the COVID-19 pandemic, Iraee has written public letters to call attention to the conditions for women detained at Qarchak prison.

Photo courtesy of Front Line Defenders

Iran’s judiciary chief announced in March 2020 that prisons would temporarily release approximately 70,000 people; but this excluded many people accused of national security crimes, which accounted for 14 of the at least 19 writers and public intellectuals held by Iran last year.58“UN rights chief urges Iran to release jailed human rights defenders, citing COVID-19 risk,” UN News, October 6, 2020, news.un.org/en/story/2020/10/1074722 Writers and intellectuals including Nasrin Sotoudeh and Narges Mohammadi were not among those freed in the March release.59Reuters Staff, “Iran temporarily releases 70,000 prisoners as coronavirus cases surge,” Reuters, March 9, 2020, reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-iran/iran-temporarily-releases-70000-prisoners-as-coronavirus-cases-surge-idUSKBN20W1E5 Cultural worker and scholar Aras Amiri was conditionally released from Iran’s Evin prison in April 2020 as part of a virus prevention measure; however, she was similarly ordered to return only three weeks later.60Patrick Wintour, “Fears rise Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe may be returned to Iran jail,” The Guardian, May 5, 2020, theguardian.com/news/2020/may/05/fears-rise-nazanin-zaghari-ratcliffe-may-be-returned-to-iran-jail

In April 2020, Turkey’s parliament passed a law that reduced prison populations by a third,61Al-Monitor Staff, “Turkey to release thousands of prisoners as coronavirus sweeps through jails,” Al-Monitor, April 14, 2020, al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2020/04/turkey-release-thousands-prisoners-coronavirus-outbreak-jail.html but this excluded people accused of crimes against the state.62Emma Sinclair-Webb, “Turkey Should Protect All Prisoners from Pandemic,” Dispatch, March 23, 2020, hrw.org/news/2020/03/23/turkey-should-protect-all-prisoners-pandemic; Kareem Fahim, “Turkish dissidents remain jailed as thousands of inmates are released to avoid prison epidemic,” The Washington Post, April 22, 2020, washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/turkish-dissidents-remain-jailed-as-thousands-of-inmates-are-released-to-avoid-prison-epidemic/2020/04/22/8570e65a-83ea-11ea-81a3-9690c9881111_story.html As such, even writers and public intellectuals more senior in age or with existing medical conditions, such as 71-year-old novelist Ahmet Altan, were not granted release.

In India, one estimate reports that by July 2020, prisons had released approximately 61,000 people by order of the Supreme Court to reduce overcrowding,63John Letzing, “How prison populations can be protected from Covid-19,” The Print, July 5, 2020, theprint.in/features/how-prison-populations-can-be-protected-from-covid-19/453095/;

“STATE/UT WISE PRISONS RESPONSE TO COVID 19 PANDEMIC IN INDIA,” Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, Accessed on March 18, 2021, humanrightsinitiative.org/content/stateut-wise-prisons-response-to-covid-19-pandemic-in-india but despite a plea for medical bail filed by poet Varavara Rao’s wife,64Press Trust of India, “Since Feb 2020, Varavara Rao Has Spent 149 Days In Hospitals: High Court Told,” NDTV, February 2, 2021, ndtv.com/india-news/since-feb-2020-varavara-rao-has-spent-149-days-in-hospitals-high-court-told-2361535 Rao was only granted a six-month medical furlough approximately six months after his positive COVID-19 diagnosis. Rao was released from custody on March 6, 2021, despite the National Investigation Agency (NIA) claiming that he was taking “undue advantage” of the pandemic.65Apoorva Mandhani, “2 years, 3 charge sheets & 16 arrests—Why Bhima Koregaon accused are still in jail,” The Print, October 31, 2020, theprint.in/india/2-years-3-charge-sheets-16-arrests-why-bhima-koregaon-accused-are-still-in-jail/533945/; “‘Free At Last’: Poet Varavara Rao, 81, Released After Last Month’s Bail,” NDTV, March 7, 2021, ndtv.com/india-news/free-at-last-poet-varavara-rao-81-released-after-last-months-bail-2385277 In Egypt, journalist and Cairo University professor Hassan Nafaa was released from custody on March 19, 2020, along with 14 other prominent opposition figures and political prisoners,66Gamal Essam El-Din, “Egypt: Political activists released,” Ahram Online, March 26, 2020, english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/50/1201/365939/AlAhram-Weekly/Egypt/Egypt-Political-activists-released.aspx a move to seemingly reduce overcrowding in the prison and avoid a coronavirus outbreak among prisoners. Yet experts estimate that Egypt continues to hold tens of thousands of political prisoners, and overcrowding and neglect threaten all those in its prisons.67Amnesty International, “Egypt: What do I care if you die,” Amnesty International, accessed March 24, 2021, amnesty.org/download/Documents/MDE1235382021ENGLISH.pdf; Ruth Michaelson, “Egypt’s political prisoners ‘denied healthcare and subject to reprisals’,” The Guardian, January 26, 2021, theguardian.com/global-development/2021/jan/26/egypts-political-prisoners-denied-healthcare-and-subject-to-reprisals

In December 2020, Eritrean authorities released 28 prisoners of conscience imprisoned in relation to their membership of the Jehovah’s Witnesses group.68Reuters Staff, “Eritrea frees 28 Jehovah’s Witnesses prisoners, group says,” Reuters, December 7, 2020, reuters.com/article/eritrea-politics-religion/eritrea-frees-28-jehovahs-witnesses-prisoners-group-says-idUSKBN28H1IE The Eritrean government, however, has not answered calls to release the several writers detained in 2001 on spurious terrorism charges, including writer and playwright Dawit Isaak and short-fiction writer Idris Said.69United Nations, “Independent Experts Denounce Rights Violations in Occupied Palestinian Territory, Iran, Eritrea as Third Committee Delegates Split over Questions of Bias,” press release, October 26, 2020, un.org/press/en/2020/gashc4302.doc.htm Saudi anti-corruption columnist Saleh Al-Shehi was released from prison in May 2020, but he was immediately hospitalized and placed on a ventilator for three weeks before passing away on June 19.70“Saudi writer dies from COVID-19 shortly after release from prison,” Middle East Monitor, July 20, 2020, middleeastmonitor.com/20200720-saudi-writer-dies-from-covid-19-shortly-after-release-from-prison/ Some report that he contracted COVID-19 in prison, while others state his health had already deteriorated after years of imprisonment.71“Saudi Arabia: Writer and journalist Saleh Al-Shehi dies following release from prison,” The Gulf Centre for Human Rights, July 20, 2020, gc4hr.org/news/view/2430; “Saudi writer dies from COVID-19 shortly after release from prison.” Al-Shehi had been arrested in January 2018 and sentenced to five years in prison for “insulting the royal court.”72“Saudi writer dies from COVID-19 shortly after release from prison.”

Isolation and Delayed Proceedings

Authorities have also invoked the pandemic to justify the isolation of imprisoned writers from their families and to delay legal proceedings. In May, Saudi prison officials reportedly invoked COVID-19 as a justification for denying Loujain Al-Hathloul the opportunity to see her family, despite her earlier contact with her family during the pandemic.73Chantal Da Silva, “Saudi Women’s Rights Activist Detained for Two Years While Awaiting Trial Must Be Released During Pandemic, Sister Says,” Newsweek, May 15, 2020, newsweek.com/saudi-womens-rights-activist-detained-two-years-while-awaiting-trial-must-released-during-1504160 In late August 2020, Al-Hathloul went on a six-day hunger strike to protest the denial of all communication with her family, with her sister noting that they had any contact with her since early June abrupt denial of outside communication; authorities finally permitted her to see her family on August 31.74MEE Staff, “Saudi activist Loujain al-Hathloul’s health ‘deteriorating’ amid hunger strike,” Middle East Eye, September 1, 2020, middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-activist-loujain-hathloul-hunger-strike Public reporting indicates that such communication denials appeared to be aimed at the kingdom’s most prominent detainees, demonstrating a political motivation.75Vivan Nereim, “Saudi Arabia’s Most Famous Prisoners Go Silent During Pandemic,” Bloomberg News, August 25, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-08-26/saudi-arabia-s-most-famous-prisoners-go-silent-during-pandemic?sref=p1whY86y

In January 2020, prisons in the UAE ended all in-person visits due to COVID-19 restrictions and moved to providing communication via phone calls.76“United Arab Emirates: Ahmed Mansoor denied contact with his family, remains in prison in unsanitary conditions,” The Gulf Centre for Human Rights, June 6, 2020, gc4hr.org/news/view/2408; “Covid-19 continues to spread in UAE prisons,” Middle East Monitor, June 22, 2020, middleeastmonitor.com/20200622-covid-19-continues-to-spread-in-uae-prisons/ However, for at least several months, imprisoned Emirati poet Ahmed Mansoor was not even able to communicate with his family via phone.77“United Arab Emirates: Ahmed Mansoor denied contact with his family, remains in prison in unsanitary conditions.” At Guanghua Prison in Hubei Province, China, writer Qin Yongmin was denied virtual communication ostensibly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the end of the lockdown in Hubei two months prior.78Chinese Human Rights Defenders, “China: Stop Using COVID-19 for Unnecessary Restrictions on Detainees’ Visitation Rights,” Chinese Human Rights Defenders, June 22, 2020, nchrd.org/2020/06/china-stop-using-covid-19-for-unnecessary-restrictions-on-detainees-visitation-rights/ While prisons are obligated to implement reasonable COVID-19 prevention measures, these cannot justify the denial of opportunities for remote communications.

While many countries faced challenges in keeping court proceedings moving during the pandemic, the conditions imposed by COVID-19 also created a convenient excuse for drawing out the legal processes for a number of writers and intellectuals. In several countries, in-person court proceedings were stalled for long periods of time, leaving many ongoing cases in limbo and further prolonging the incarceration of unjustly detained people. In May 2020, after Saudi courts closed due to COVID-19, the trial proceedings of several women activists and writers who had already spent two years in arbitrary detention, including Loujain Al-Hathloul, Nassima Al-Sadah, and Nouf Abdulaziz, were postponed for months.79“Continuing arbitrary detention of Mses. Loujain al-Hathloul, Mayaa al-Zahrani, Samar Badawi, Nassima al-Sadah and Nouf Abdelazi,” World Organisation Against Torture, March 19, 2020, omct.org/human-rights-defenders/urgent-interventions/saudi-arabia/2020/03/d25746/ In December 2020, authorities delayed court proceedings against Sri Lankan poet Ahnaf Jazeem by several months due to COVID-19. Jazeem was arrested in May 2020 under the Prevention of Terrorism Act, with authorities speciously claiming that he promoted extremism in his book of poetry Navarasam.80“Poetic injustice: Another writer languishes in prison under PTA in Sri Lanka,” Sri Lanka Brief, December 14, 2020, srilankabrief.org/poetic-injustice-another-writer-languishes-in-prison-under-pta/; Ruwan Laknath Jayakody, “Complaint Lodged With HRCSL Over Poet Ahnaf Jazeem Detained Under PTA,” Colombo Telegraph, December 31, 2020, colombotelegraph.com/index.php/complaint-lodged-with-hrcsl-over-poet-ahnaf-jazeem-detained-under-pta/ Imprisoned Cameroonian writer and filmmaker Tsi Conrad’s appeal has been upended by COVID-19’s impact on court proceedings, to the point where Conrad received a new judge in October and was forced to start the appeals process from the beginning. In all, Conrad’s appeal has been postponed seven times, a delay of over a year.81“Tsi Conrad,” Committee to Protect Journalists, accessed March 24, 2021, cpj.org/data/people/tsi-conrad/

Countries of Concern

China, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey continue to lead in the concentrated targeting of writers and intellectuals, with each holding more than 20 detained or imprisoned writers in 2020, and China alone accounting for 81 of the writers and intellectuals held behind bars last year.

In China, which includes the Xinjiang and Tibetan Autonomous Regions, Inner Mongolia, and Hong Kong, the total number increased from the previous year, from 73 to 81. The totals for China—excluding the autonomous or special administrative regions of Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and Hong Kong—and Tibet both increased, in substantial part as a result of the targeting of writers and online commentators who spoke out about the government’s handling of and response to the emergence of COVID-19.

Within China (excluding Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Hong Kong), PEN America places the number of imprisoned writers or public intellectuals at 39. Many of these writers are political dissidents who have been targeted for their criticism of the Chinese Communist Party; people like the 2020 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award honoree Xu Zhiyong, who was arrested in February while in hiding from the police and after penning an essay critical of President Xi Jinping’s leadership, including his handling of the COVID-19 outbreak, and calling on Xi to resign.82Emily Feng, “Rights Activist Xu Zhiyong Arrested In China Amid Crackdown On Dissent,” NPR, February 17, 2020, npr.org/2020/02/17/806584471/rights-activist-xu-zhiyong-arrested-in-china-amid-crackdown-on-dissent Initially charged with “inciting subversion,” the charges against Xu were reportedly upgraded in January 2021 to “subversion of state power,” which carries a potential life sentence.83PEN America, “Reports: China to Escalate Charges Against Pen America Honoree Xu Zhiyong,” press release, January 22, 2020, pen.org/press-release/reports-china-to-escalate-charges-against-pen-america-honoree-xu-zhiyong/ Xu has also reported being tortured while in custody.84Guo Rui, “China arrests girlfriend of detained legal activist Xu Zhiyong on subversion charge,” South China Morning Post, March 15, 2021, scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3125558/china-arrests-girlfriend-detained-legal-activist-xu-zhiyong Others detained in China this past year for their criticism of the Party or its leadership include scholar Chen Zhaozhi, who has been detained since March 2020 and is facing charges of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” for his criticism of the government’s response to COVID;85“Chen Zhaozhi,” Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), August 28, 2020, nchrd.org/2020/08/chen-zhaozhi/ and poet Zhang Guiqi, facing charges of “inciting subversion” after publicly calling for President Xi’s resignation in May 2020.86Taiwan News, “Chinese poet arrested for demanding Xi’s resignation in online video,” Taiwan News, June 23, 2020, taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3951952

Others have been targeted for speaking out against official discrimination toward minority groups in China or against local-level corruption. The poet Cui Haoxin, who has consistently spoken out against the discriminatory treatment of Muslims in the country, including the abuses in Xinjiang, was arrested in January 2020 similarly on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking troubles.”87Sing Man, Ng Yik-tung, and Wang Yun, “China Detains Hui Muslim Poet Who Spoke Out Against Xinjiang Camps,” Radio Free Asia, January 27, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/china/poet-01272020163336.html Little is known about his case, his detention conditions, or even if he has received a trial date, and he has spent the last year incommunicado. Journalist Chen Jieren was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment in 2020, following two years of incommunicado detention, after blogging about allegations of corrupt local officials.88Wang Zhicheng, “Journalist Chen Jieren gets 15 years for ‘denigrating’ the Communist Party with corruption charges,” AsiaNews.it, May 2, 2020, asianews.it/news-en/Journalist-Chen-Jieren-gets-15-years-for-%E2%80%9Cdenigrating%E2%80%9D-the-Communist-Party-with-corruption-charges-49976.html Consistent with its broader, ever-increasing efforts to stifle dissent and control expression, the Chinese Communist Party continues to treat peaceful criticism of its rule as a heinous crime.

Yet one does not have to criticize the government or its policies to run afoul of Beijing’s criminalization of vast categories of speech. Graphic novelist Liu Tianyi remains in prison serving a 10-year sentence for her homoerotic novel Occupy, after being sentenced in 2018. Writer and photographer Du Bin was detained in December for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a month before the publication of his book analyzing early Soviet Communism—seeming to indicate that even historical inquiry that touches indirectly on the Chinese Communist Party’s governance may be subject to a governmental “veto” in the form of criminal charges. Authorities also questioned Du about his previous books, before eventually releasing him conditionally after 37 days.89Gao Feng, “Author Du Bin, a writer suspected of being manipulated by foreign organizations, was released from criminal detention for more than a month,” Radio Free Asia, January 26, 2021, rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/renquanfazhi/gf2-01262021085156.html (Mandarin: 高锋, “疑受境外组织操控出书 作家杜斌被刑拘逾月终获释,” 自由亚洲电台, January 26, 2021, rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/renquanfazhi/gf2-01262021085156.html)

A small but important subset of imprisoned writers in China are citizens of other countries. Chinese-born Swedish poet and publisher Gui Minhai, who was kidnapped from his vacation home in Thailand by Chinese security agents in 2015, was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment in February 2020 for “illegally providing evidence overseas”—a charge seemingly related to Gui having been in touch with his own country’s consular officials.90Lily Kuo, “Hong Kong bookseller Gui Minhai jailed for 10 years in China,” The Guardian, February 25, 2020, theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/25/gui-minhai-detained-hong-kong-bookseller-jailed-for-10-years-in-china Gui’s case is particularly urgent as he has reportedly been diagnosed with the neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.91“Detained bookseller Gui Minhai had been told to seek medical treatment for ALS overseas, daughter says,” South China Morning Post, January 25, 2018, scmp.com/yp/discover/news/asia/article/3069441/detained-bookseller-gui-minhai-had-been-told-seek-medical Beijing has repeatedly ignored or denied that Gui is a Swedish citizen, at one point even claiming that Gui had conveniently renounced his Swedish citizenship while imprisoned.92Peter Dahlin, “Jailed bookseller: With Gui Minhai citizenship ploy, Beijing infringes int’l law and its own rules,” Hong Kong Free Press, February 29, 2020, hongkongfp.com/2020/02/29/jailed-bookseller-gui-minhai-citizenship-ploy-beijing-infringes-intl-law-rules/ Yang Hengjun, a Chinese-born Australian writer, was detained during a visit to China in January 2019, and officially charged with espionage in October 2020, after reportedly being subjected to hundreds of interrogation sessions.93Kirsty Needham, “Detained Australian Yang Hengjun set to face trial in Beijing,” Reuters, October 9, 2020, reuters.com/article/uk-australia-china-writer/detained-australian-yang-hengjun-to-face-trial-in-beijing-idUKKBN26V031 These cases appear to indicate an ever-more-muscular approach from Beijing toward silencing its critics, wherever they may be.

We include six cases from Tibet, a number double that of last year’s three cases. This number increased, in major part, as a result of public reporting revealing that singer-songwriters Lhundrub Drakpa and Khando Tsetan had been detained in 2019 and sentenced in 2020 on national security charges in relation to their music.94“China imprisons two Tibetans for song praising His Holiness the Dalai Lama,” Central Tibetan Administration, July 21, 2020, tibet.net/china-imprisons-two-tibetans-for-song-praising-his-holiness-the-dalai-lama/; “Tibetan Singer Sentenced to Six Years in Prison in Driru: China Committing ‘Crimes against Humanity’ in Tibet,” Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, October 30, 2020, tchrd.org/tibetan-singer-sentenced-to-six-years-in-prison-in-driru-china-committing-crimes-against-humanity-in-tibet/ The third addition to the 2020 Index from the previous year, poet and essayist Gendun “Lhamko” Lhundrub, was detained in December.95“Tibetan Writer Arrested in Qinghai, Whereabouts Unknown,” Radio Free Asia, December 4, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/tibet/writer-12042020164144.html; “Tibetan writer arrested, whereabouts remain unknown,” Phayul, December 7, 2020, phayul.com/2020/12/07/44897/ As we discuss further within this report, it remains the case that writers and public intellectuals who advocate for Tibetan cultural expression or decry CCP policies affecting Tibetans risk being treated as national security threats for their peaceful expression.

In Hong Kong, academics and writers who led pro-democracy movements in previous years continued to face severe threats. The total number of writers and intellectuals imprisoned in 2020 in Hong Kong is comparatively low—only three cases, down from last year’s six. This number, however, fails to capture the devastating and chilling effect that the passage of Hong Kong’s repressive National Security Law in June has had on freedom of expression in the city.96“Hong Kong’s national security law: 10 things you need to know,” Amnesty International, July 17, 2020, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/07/hong-kong-national-security-law-10-things-you-need-to-know/ With the swift implementation of the National Security Law, writers and public intellectuals have encountered strict limitations on acceptable literature, school curriculum, and the press, while the specter of criminal charges looms over anyone who would participate in or even support the city’s besieged pro-democracy movement. The numbers for Hong Kong also do not incorporate the stunning arrest of over 50 pro-democracy leaders in January of 2021—outside the time frame of the 2020 Index—under this same law, a sweeping political purge that illustrates the draconian nature of the law as well as Beijing’s willingness to ruthlessly repress protest and civic debate in the region.97Rebecca Falconer, “Hong Kong police arrest 50 pro-democracy leaders under security law,” Axios, January 6, 2021, axios.com/hong-kong-police-arrest-50-pro-democracy-activists-under-security-law-a0cde4ca-c009-48fb-ba1c-828e47ff6736.html

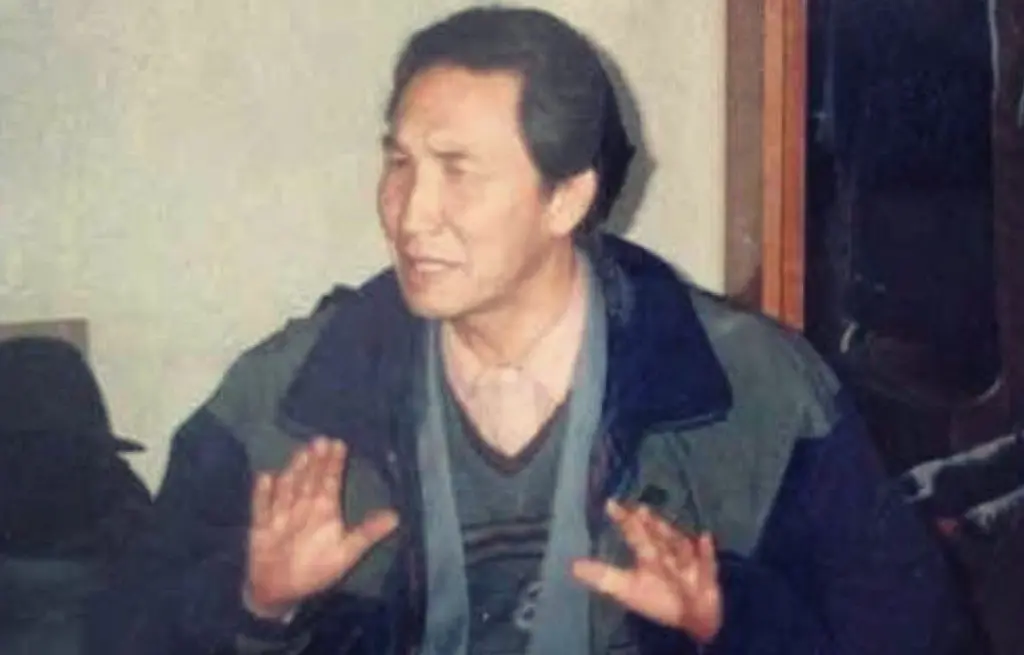

Qurban Mamut

China/Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

Status: Detained

While information about his detention is limited, the detention of Mamut, a prominent Uyghur literary and cultural figure, is emblematic of the Chinese government’s ongoing assault on Uyghur culture.

Photo courtesy of Bahram Sintash

The total for Xinjiang stands at 33, nearly equivalent to last year’s figure of 32. However, as we similarly noted in last year’s Freedom to Write Index, this figure is certainly an incomplete accounting of the real number of detained and imprisoned writers and intellectuals among the vast number of people unjustly detained in Xinjiang, given the government’s highly effective tactics to essentially cut off the region from the rest of the world—from censoring domestic media, to restricting foreign media access, to imposing totalitarian levels of control over the populace itself.98For additional information on the detention of writers, intellectuals, and other cultural figures in Xinjiang, see the following reports from the Uyghur Human Rights Project: Detained and Disappeared: Intellectuals Under Assault in the Uyghur Homeland, March 25, 2019, uhrp.org/report/detained-and-disappeared-intellectuals-under-assault-uyghur-homeland-html/; UHRP Update: The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region Continues, January 28, 2019, uhrp.org/report/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-continues-html/; UHRP Report: The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region: Disappeared Forever?, October 2018, uhrp.org/report/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-disappeared-forever-html/

The figures for Xinjiang include some of the leading lights of the region’s literary and cultural community. Chimengül Awut, an award-winning poet and editor, was sent to a “re-education camp” in 2018 after editing a novel by another Uyghur writer, until she was finally released in December 2020.99Lily Kuo, “Poetry, the soul of Uighur culture, on verge of extinction in Xinjiang,” The Guardian, December 5, 2020, theguardian.com/world/2020/dec/06/poetry-the-soul-of-uighur-culture-on-verge-of-extinction-in-xinjiang; PEN International, “We have just received new information which supports reports that Uyghur-language poet, Chimengül Awut, has been released from Xinjiang’s re-education camps’” Twitter, December 5, 2020, twitter.com/pen_int/status/1335334475258064901 Qurban Mamut, the former editor-in-chief of the journal Xinjiang Civilization, went missing in November 2017, and it took almost a year before his family was able to confirm he was being held in an internment camp—where he presumably is still located.100Shohret Hoshur and Joshua Lipes, “Prominent Uyghur Journalist Confirmed Detained After Nearly Three Years,” Radio Free Asia, September 6, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detained-06092020170643.html Abdurehim Heyit, a Uyghur folk musician, similarly disappeared in 2017, before resurfacing in 2019 with a “proof of life” video that is widely believed to have been coerced by government officials.101“Abdurehim Heyit Chinese video ‘disproves Uighur musician’s death,’” BBC, February 11, 2019, bbc.com/news/world-asia-47191952 Heyit similarly remains cut off from the wider world to this day.

In 2020, the world continued to learn new information about other Uyghur writers who had gone missing. Songwriter and comedian Ablikim Kalkun was handed an 18-year sentence in 2019 for crimes including “separatism” and “religious extremism” after singing songs that authorities disapproved of. Yet his sentence was only confirmed in 2020, after an anonymous source tipped off Radio Free Asia reporters.102Shohret Hoshur and Joshua Lipes, “Xinjiang Authorities Jail Prominent Uyghur Comedian Over ‘Extremist and Separatist’ Songs,” Radio Free Asia, October 6, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/comedian-10062020124834.h The first public claims over Kalkun’s detention, of which PEN America is aware, date back to 2019, from activist Abduweli Ayup, on his Facebook page: m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2788286744540533&id=100000777053688 Similarly, poet Qasim Sidiq was disappeared by authorities in 2017 after they alleged he had incited “ethnic hatred” with his song lyrics and poems, yet his detention was only confirmed in 2021.103Shohret Hoshur and Joshua Lipes, “Missing Uyghur Poet and Teacher Confirmed Detained After Nearly Four Years,” Radio Free Asia, January 1, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/poet-01072021174718.html

The government’s targeting of writers, cultural figures, academics, and others in the region is deliberate, and part and parcel of its larger efforts to systemically erase Uyghur culture and forcibly remake Uyghurs into obedient subjects of the state—efforts that have led to the forced internment of over a million people,104“China: Massive Numbers of Uyghurs & Other Ethnic Minorities Forced into Re-education Programs,” CHRD, August 3, 2018, nchrd.org/2018/08/china-massive-numbers-of-uyghurs-other-ethnic-minorities-forced-into-re-education-programs/; see also “China: Massive Crackdown in Muslim Region,” Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2018, hrw.org/news/2018/09/09/china-massive-crackdown-muslim-region the omnipresent and dystopian surveillance regime that authorities have set up in the region,105Chris Buckley and Paul Mozur, “How China Uses High-Tech Surveillance to Subdue Minorities,” The New York Times, May 22, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/05/22/world/asia/china-surveillance-xinjiang.html; Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, “The Xinjiang Papers—‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims,” The New York Times, November 16, 2019, nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html; “China: Minority Region Collects DNA from Millions,” Human Rights Watch, December 13, 2017, hrw.org/news/2017/12/13/china-minority-region-collects-dna-millions; “China: Voice Biometric Collection Threatens Privacy,” Human Rights Watch, October 22, 2017, hrw.org/news/2017/10/22/china-voice-biometric-collection-threatens-privacy and the de facto criminalization of Uyghur cultural and religious expression.106“More Evidence of China’s Horrific Abuses in Xinjiang,” Human Rights Watch, February 20, 2020, hrw.org/news/2020/02/20/more-evidence-chinas-horrific-abuses-xinjiang

PEN America’s figures also include writers and intellectuals imprisoned before the systemic internment of Uyghurs began in 2017, demonstrating that these attacks on Uyghur culture did not originate with the camps.107“China: Free Xinjiang ‘Political Education’ Detainees,” Human Rights Watch, September 10, 2017, hrw.org/news/2017/09/10/china-free-xinjiang-political-education-detainees Gulmira Imin, a poet and Uyghur-language website moderator, was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2010 on “splittism” and other charges.108Mamatjan Juma and Alim Seytoff, “‘Gulmira Imin Must Not be Forgotten’,” Radio Free Asia, February 16, 2018, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/forgotten-02162018163053.html She remains in prison to this day, as does Ilham Tohti, an economics professor and the 2014 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award honoree, whose blog on Uyghur-Han relations served as the basis for national security charges against him.109“Ilham Tohti: Uighur activist’s daughter fears for his life,” BBC, December 18, 2019, bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-50842514 He is currently serving a life sentence. As the wider world becomes more aware of the CCP’s abuses in Xinjiang, these cases serve as potent reminders that the cultural oppression of the Uyghurs has been ongoing for many years. Writers and intellectuals from other ethnic minorities have also been targeted. Kazakh writer Nagyz Muhammed was arrested in Xinjiang in 2018, and later sentenced to life in prison for splittism.110“China: Further information: Life imprisonment for missing Kazakh writer,” Amnesty International, October 29, 2020, amnesty.org/download/Documents/ASA1732792020ENGLISH.pdf His supposed crime was to express his opinions on policies in the region at a meeting with friends, years before.