Educational Gag Orders

Legislative Restrictions on the Freedom to Read, Learn, and Teach

Read the essay >>

This report reflects 54 educational gag orders that state legislators introduced in the first nine months of 2021.

We are actively tracking bills that emerged at later dates and updating our Index weekly.

PEN America Experts:

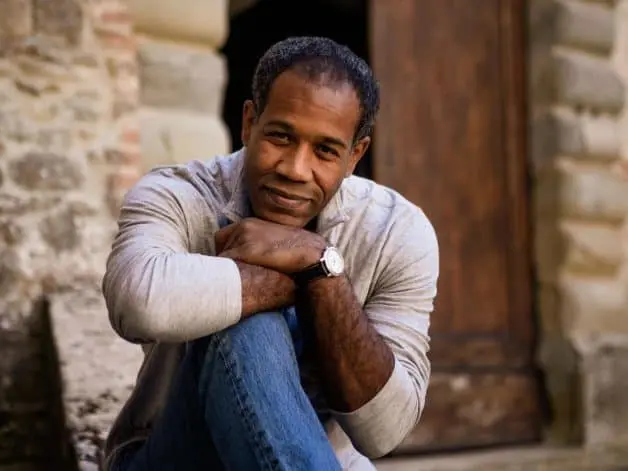

Sy Syms Managing Director, U.S. Free Expression Programs

Director, Research

Introduction

Between January and September 2021, 24 legislatures across the United States introduced 54 separate bills intended to restrict teaching and training in K-12 schools, higher education, and state agencies and institutions. The majority of these bills target discussions of race, racism, gender, and American history, banning a series of “prohibited” or “divisive” concepts for teachers and trainers operating in K-12 schools, public universities, and workplace settings. These bills appear designed to chill academic and educational discussions and impose government dictates on teaching and learning. In short: They are educational gag orders.

Collectively, these bills are illiberal in their attempt to legislate that certain ideas and concepts be out of bounds, even, in many cases, in college classrooms among adults. Their adoption demonstrates a disregard for academic freedom, liberal education, and the values of free speech and open inquiry that are enshrined in the First Amendment and that anchor a democratic society. Legislators who support these bills appear determined to use state power to exert ideological control over public educational institutions. Further, in seeking to silence race- or gender-based critiques of U.S. society and history that those behind them deem to be “divisive,” these bills are likely to disproportionately affect the free speech rights of students, educators, and trainers who are women, people of color, and LGBTQ+. The bills’ vague and sweeping language means that they will be applied broadly and arbitrarily, threatening to effectively ban a wide swath of literature, curriculum, historical materials, and other media, and casting a chilling effect over how educators and educational institutions discharge their primary obligations. It must also be recognized that the movement behind these bills has brought a single-minded focus to bear on suppressing content and narratives by and about people of color specifically–something which cannot be separated from the role that race and racism still plays in our society and politics. As such, these bills not only pose a risk to the U.S. education system but also threaten to silence vital societal discourse on racism and sexism.

In this report, we have focused our examination on state-level legislation, as state governments have primary authority over public education. However, the language in many of these bills has also appeared elsewhere: in bills and proposals introduced at the federal level, within other state organs, and in local school boards. Arriving alongside similar waves of legislation to restrict voting and protest rights, these censorious bills reflect a larger and worrying anti-democratic trend in U.S. politics, in which lawmakers use the machinery of government in attempts to limit Americans’ ability to express themselves—and particularly in order to block the expression of ideas or sentiments the lawmakers oppose.

It is not a coincidence that this legislative onslaught followed the mass protests that swept the United States in 2020 in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. As many Americans and U.S. institutions have attempted a true reckoning with the role that race and racism play in American history and society, those opposed to these cultural changes surrounding race, gender, and diversity have pushed back ferociously, feeding into a culture war. Certain Republican legislators and conservative activists have capitalized on this backlash, borrowing the name of an academic framework — critical race theory (CRT) — and inaccurately applying it to a range of ideas, practices, and materials related to advancing diversity, equity, or inclusion. The individual behind the Trump Administration executive order (EO) that inspired many of these bills—Manhattan Institute senior fellow Christopher Rufo–acknowledges that he intentionally uses the label to rally political support, saying that CRT is “the perfect villain” and a useful “brand category” to build opposition to progressives’ perceived dominance of American educational institutions.1Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “How a Conservative Activist Invented the Conflict Over Critical Race Theory,” New Yorker, June 18, 2021, newyorker.com/news/annals-of-inquiry/how-a-conservative-activist-invented-the-conflict-over-critical-race-theory; @realchrisrufo, March 15, 2021, twitter.com/realchrisrufo/status/1371541044592996352 This “Critical Race Theory” framing device has been applied with a broad brush, with targets as varied as The New York Times’ 1619 Project, efforts to address bullying and cultural awareness in schools,2Leah Asmelah, “A School District Tried to Address Racism, a Group of Parents Fought Back,” CNN, May 10, 2021, cnn.com/2021/05/05/us/critical-race-theory-southlake-carroll-isd-trnd/index.html and even the mere use of words like “equity, diversity, and inclusion,” “identity,” “multiculturalism,” and “prejudice.”3Brigid Kennedy, “Texas Nonprofit Shares Bizarre Cheat Sheet for Identifying CRT Buzzwords in the Classroom,” The Week, June 30, 2021, theweek.com/us/1002125/texas-nonprofit-shares-bizarre-cheat-sheet-for-identifying-crt-buzzwords-in-the; Reid Wilson, “‘Woke,’ ‘Multiculturalism,’ ‘Equity’: Wisconsin GOP Proposes Banning Words from Schools,” The Hill, September 29, 2021, thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/574567-woke-multiculturalism-equity-wisconsin-gop-proposes-banning-words-from

To justify their censorious proposals, the bills’ proponents have also seized on a series of episodes related to diversity and teaching about racism in schools to stoke fears over “critical race theory” run amok, and adopted spurious and inflammatory characterizations of theories and programs as “Marxist,” “un-American,” and existentially threatening to American values and institutions. As author and literary critic Jeet Heer has written, these attacks follow “an old script, one where the name of the bogeyman changes but the basic storyline is always the same: sinister, alien forces are trying to corrupt children. We’ve seen this before in the battles over teaching evolution, over prayer in the schoolroom, over LGBTQ teachers, over sex ed, over trans students, over bathrooms, among others.”4Jeet Heer, “Critical Race Theory and ‘the children,’” Substack, June 12, 2021, jeetheer.substack.com/p/critical-race-theory-and-the-children

Yet while these tactics may be old, they are also powerfully tied to the current political and social moment. As historian and writer Jelani Cobb starkly described on Twitter, “The attacks on critical race theory are clearly an attempt to discredit the literature millions of people sought out last year to understand how George Floyd wound up dead on a street corner. The goal is to leave the next dead black person inexplicable by history.”5Jelani Cobb, Twitter, June 11, 2021, twitter.com/jelani9/status/1403401984254758914

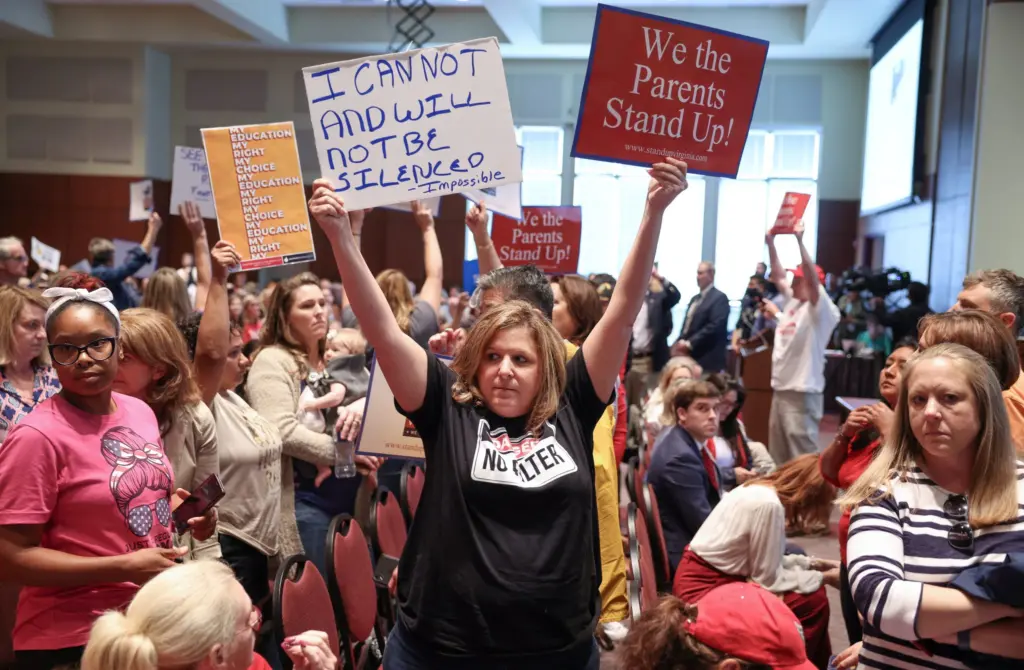

Eleven of these bills have already become law in nine states, while similar legislation is pending across the country. Beyond statehouses, national and local organizations are actively pressuring school boards, principals, university regents, and state educational agencies to ban the teaching of certain ideas and content. Political action committees (PACs) have formed to campaign against elected school board officials who do not support these bans. Parents who have been recruited to join the campaign have reportedly harassed local elected leaders and school administrators and disrupted public meetings.6Tyler Kingkade, Brandy Zadrozny, and Ben Collins, “Critical race theory battle invades school boards—with help from conservative groups,” NBC News, June 15, 2021, nbcnews.com/news/us-news/critical-race-theory-invades-school-boards-help-conservative-groups-n1270794 The tensions are so feverish that local officials have turned to the federal government for help, asking for heightened security at local school board meetings.7National School Boards Association Asks for Federal Assistance to Stop Threats and Acts of Violence Against Public Education Leaders, National School Boards Association, Sept. 30, 2021, nsba.org/News/2021/federal-assistance-letter; Jennifer Calfas, “School Boards Ask for Federal Help as Tensions Rise Over Covid-19 Policies,” The Wall Street Journal, Sept. 30, 2021

These bills will have—and are already having—tangible consequences for both American education and democracy, both distorting the lens through which the next generation will study American history and society and undermining the hallmarks of liberal education that have set the U.S. system apart from those of authoritarian countries. In a very short time, we have already seen the chilling effects of this kind of legislation, which has been used to justify suspending a sociology course on race and ethnicity in Oklahoma,8Hannah Knowles, “Critical race theory ban leads Oklahoma college to cancel class that taught ‘white privilege’,” The Washington Post, May 29, 2021, washingtonpost.com/education/2021/05/29/oklahoma-critical-race-theory-ban/ providing professors at Iowa State University written guidance for how to avoid ‘drawing scrutiny’ for their teaching under their state’s Act,9

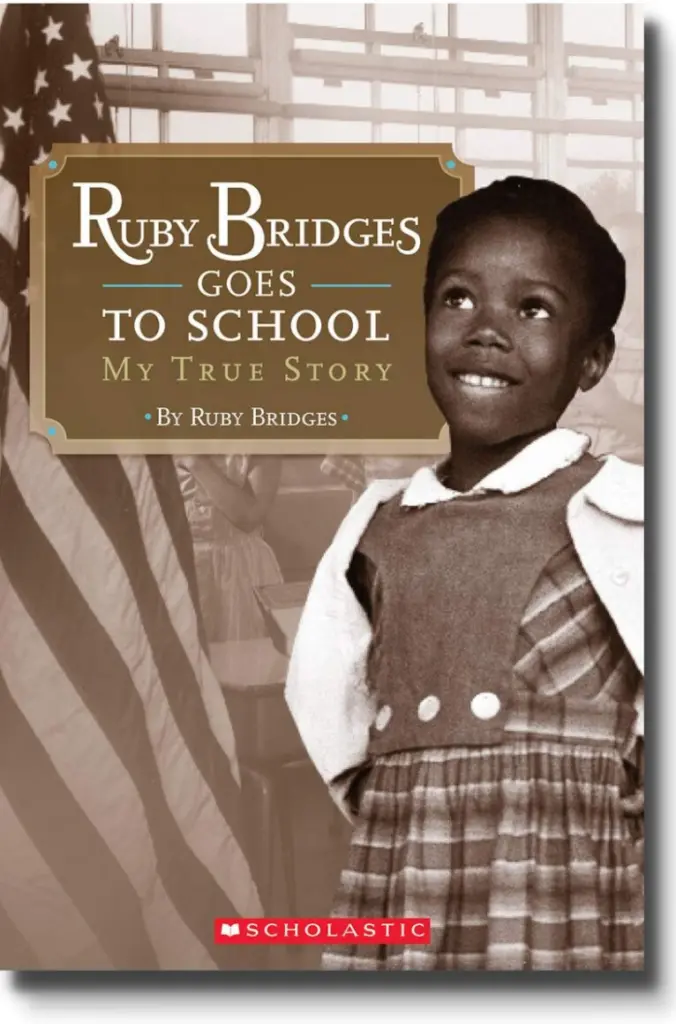

Iowa State University — Frequently Asked Questions — Iowa House File 802 — Requirements Related to Racism and Sexism Trainings at Public Postsecondary Institutions, August 5, 2021, https://www.provost.iastate.edu/policies/iowa-house-file-802—requirements-related-to-racism-and-sexism-trainings; Daniel C. Vock, “GOP furor over ‘critical race theory’ hits college campuses,” Iowa Capital Dispatch, July 3, 2021, iowacapitaldispatch.com/2021/07/03/gop-furor-over-critical-race-theory-hits-college-campuses/ instructing teachers that they should balance having books on the Holocaust with those with “opposing views” in Texas,10Mike Hixenbaugh and Antonia Hylton, “Southlake school leader tells teachers to balance Holocaust books with ‘opposing’ views,” October 14, 2021, nbcnews.com/news/us-news/southlake-texas-holocaust-books-schools-rcna2965 and challenging the teaching of civil rights activist Ruby Bridges’s autobiographical picture book about school desegregation in Tennessee.11Brendan Morrow, “Anti-critical race theory parents reportedly object to teaching Ruby Bridges book,” The Week, July 8, 2021, theweek.com/news/1002407/anti-critical-race-theory-parents-reportedly-object-to-teaching-ruby-bridges-book

PEN America intends this report to sound the alarm and recognize these bills for what they are: attempts to legislate constraints on certain depictions or discussions of United States history and society in educational settings; to stigmatize and suppress specific intellectual frameworks, academic arguments, and opinions; and to impose a particular political diktat on numerous forms of public education. Taken together, these efforts amount to a sweeping crusade for content- and viewpoint-based state censorship.

For this reason, we refer to these bills not by incomplete or misleading terms like “anti–critical race theory,” or “divisive concepts”—as their proponents prefer—but rather by a more accurate description: educational gag orders. We use this term because we believe that it best captures the actual and intended effect of these bills: to stop educators from introducing specific subjects, ideas, or arguments in classroom or training sessions.

This report does not evaluate the pedagogical benefits or drawbacks of specific curricular materials, educational approaches, intellectual frameworks, or professional trainings. Our efforts stem from PEN America’s mission as a literary and human rights organization to stand for the free flow of ideas, an abiding commitment to the freedom to write and the freedom to read—and, when it comes to educational institutions, the freedom to learn. As such, we seek to demonstrate these bills’ censorious nature, and to call attention to their specific attempts to silence teaching and discussion regarding race and racism in U.S. history. The teaching of history, civics, and American identity has never been neutral or uncontested, and reasonable people can disagree over how and when educators should teach children about racism, sexism, and other facets of American history and society.12For a contemporary look at how Americans respond differently over questions of historical consideration in education, see “History, The Past, and Public Culture: Results from a National Survey,” American History Association & Farleigh Dickinson University, August 2021, historians.org/history-culture-survey But in a democracy, the response to these disagreements can never be to ban discussion of ideas or facts simply because they are contested or cause discomfort.13PEN America has produced three substantial reports on the tensions that can arise between advancing equity and inclusion and defending free speech in college settings, and has proposed guidance—our Campus Free Speech Guide—on how to ensure that campuses in particular remain arenas for thoughtful, even contentious debate that cuts across the ideological spectrum, while also being spaces of equal opportunity for all. As American society reckons with the persistence of racial discrimination and inequity, and the complexities of historical memory, attempts to use the power of the state to constrain discussion of these issues must be rejected.

Report Content and Structure

This report offers an in-depth analysis of these state legislative efforts from January to September, 2021. We document the origins and extensive spread of various proposals and describe the many legal, constitutional, and civic concerns they raise.

In Section I, we discuss the origins of this year’s educational gag orders, tracing the transition from rhetoric used by former President Donald Trump into a widespread Republican policy push. In Section II, we summarize the 54 state-level bills introduced this year, tracing common patterns. In Section III, we discuss the worrying political context in which these bills have arisen and elaborate on the way many legislators have held out a false conception of critical race theory as a bogeyman and political wedge for the next election cycle. While there has been some opposition from Republican politicians and conservative commentators, to date their voices are too few and too quiet, as educational gag orders have become increasingly normalized as a Republican legislative priority across multiple levels of government in the past year.

In Section IV, we lay out PEN America’s grave concerns with the ways these bills threaten free speech, academic freedom, and open inquiry. We examine specific provisions and language in many of the bills and explain what makes them so problematic for education in a democracy. Within this analysis, we offer four main observations about these educational gag orders:

- Each of these bills represents an effort to impose content- and viewpoint-based censorship.

- Individually and collectively, these bills will have a foreseeable chilling effect on the speech of educators and trainers: Even when crafted in ways that nominally permit free expression, they send an unmistakable signal that specific ideas, arguments, theories, and opinions may not be tolerated by the government.

- These bills are based on a misrepresentation of how intellectual frameworks are taught, and threaten to constrain educators’ ability to teach a wide range of subjects.

- Many of these bills include language that purports to uphold free speech and academic inquiry. This language, intended to help safeguard these bills from legal and constitutional scrutiny, does little or nothing to change the essential nature of these bills as instruments of censorship.

In Section V, we examine the legal and constitutional concerns with the state-level bills as a whole, detailing the existing judicial precedents that are likely to shape any legal challenges. We explain why, even if all of the laws resulting from these bills are struck down, they are still likely to have a chilling effect on education in schools, colleges, universities, and state agencies and institutions. In our Conclusion we sum up our concerns and offer some recommendations for legislators and other actors.

Overview of Bills

In writing this report, PEN America identified 54 bills, introduced or pre-filed in 24 states between January and September 2021, that we characterize as educational gag orders. As described in detail below and in the report’s index, each of these bills seeks to prohibit the teaching of specific ideas, concepts, or curricular materials in public schools, higher education, state agencies and institutions, or some combination thereof. There is, however, great variation among them. Some bills are explicit in their targets—forbidding the teaching of specific curricula or squarely banning certain concepts from the classroom. Others do not explicitly target the classroom but impose broad prohibitions on public institutions and employees, including public school teachers and college professors. Still others prohibit the introduction of specific concepts within trainings, rather than in-classroom education or curricula.

Although as of this writing few of these bills have become law, together they illustrate a disturbing willingness among Republican legislators to use the power of government to censor and restrict viewpoints, intellectual frameworks, and historical truths or narratives that they dislike:

- With only one exception, the bills appear to have been influenced by U.S. Senator Tom Cotton’s Saving American History Act, former President Trump’s 2020 Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping, or conservative lawyer Stanley Kurtz’s Partisanship Out of Civics Act. Forty-two bills have a clear antecedent in Trump’s executive order (EO), with most of them including a list of prohibited “divisive concepts” related to “race and sex stereotyping” that mirror the EO’s language, though there is some variation among the bills’ listed concepts.

- Forty-eight bills explicitly apply to teaching in some form in public schools, while 21 explicitly apply to public colleges and universities. Of the latter, 19 include restrictions on college-level teaching.

- Eleven bills explicitly prohibit schools from using materials from The New York Times’ 1619 Project, a journalistic and historical examination of the modern impact of slavery in the United States. Six bills prohibit private funding for curricula in public schools, which—given the context in which they were developed and introduced—appears similarly aimed at blocking specific educational materials that deal with racial justice and sexism.

- Nine of the bills explicitly target critical race theory (CRT), a term that has been invoked by conservative activists not on the basis of its actual meaning – namely, a specific intellectual framework developed by legal scholars – but as a catchall for any teaching on race or diversity of which they disapprove. Some bills mention CRT only in their introductory language, while others incorporate it in the actionable legislative text.

- Ten bills use the formulation of prohibiting schools, teachers, or instructors from “compelling” a person to affirm a belief in a “divisive concept.” As this report explains, by identifying a specific set of beliefs that officials must guard against, such formulations function as viewpoint-based prohibitions while masquerading as a defense of intellectual freedom.

- One bill introduced in Tennessee seeks to ban curricular materials that “promote, normalize, support, or address lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) issues or lifestyles.”14Tennessee HB 800, capitol.tn.gov/Bills/112/Bill/HB0800.pdf

- Eight bills mandate the “balanced” teaching of “controversial” political or social topics or the equal presentation of “diverse and contending views”—requirements that appear to promote evenhandedness while actually inviting partisan politics into public educational institutions.

As of this writing, eleven educational gag order bills have become law. Some completed their legislative journey in days, and all eleven passed despite strong opposition from education and civil liberties advocates.15Emerson Sykes and Sarah Hinger, “State Lawmakers Are Trying to Ban Talk About Race in Schools,” ACLU, May 14, 2021, aclu.org/news/free-speech/state-lawmakers-are-trying-to-ban-talk-about-race-in-schools/; Adrian Florido, “Teachers Say Laws Banning Critical Race Theory Are Putting a Chill on Their Lessons,” NPR, May 28, 2021, npr.org/2021/05/28/1000537206/teachers-laws-banning-critical-race-theory-are-leading-to-self-censorship; Madeline Will, “Teachers’ Unions Vow to Defend Members in Critical Race Theory Fight,” Education Week, July 6, 2021, edweek.org/teaching-learning/teachers-unions-vow-to-defend-members-in-critical-race-theory-fight/2021/07; Talia Richman, Texas Senate committee advances bill aimed at tackling ‘critical race theory’, Dallas Morning News, August 10, 2021, dallasnews.com/news/education/2021/08/10/texas-senate-committee-advances-bill-aimed-at-tackling-critical-race-theory Nine of these laws explicitly apply to public schools (one each in Arizona, Idaho, Iowa, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Tennessee, and two in Texas), three of them explicitly apply to colleges and universities (in Idaho, Iowa, and Oklahoma), and six of them explicitly apply to state agencies and institutions (one each in Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, and New Hampshire, and two in Texas).16New Hampshire’s HB 2 does not explicitly include public universities and colleges in its definition of public employers, but neither does it definitively exclude them. The ambiguity has led to concern and confusion as to whether it would implicate institutions of higher education.

Nineteen bills were introduced but did not pass, though only four of those were withdrawn. Twenty-four bills have already been introduced and could still move forward; of these, 18 remain pending from the 2021 legislative session, and six have been pre-filed for 2022.

Status of Educational Gag Orders as of October 1, 2021

| Targets | Introduced | Passed | Failed | Pending/Pre-filed |

| Public schools | 48 | 9 | 17 | 22 |

| Colleges and universities | 21 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| State agencies, institutions, and/or contractors | 19 | 6 | 5 | 8 |

| Total | 54 | 11 | 19 | 24 |

The potential chilling effect of these bills is obvious: Teachers, professors, and trainers who are afraid they might venture too close to prohibited topics will instead draw back, wary of being party to any discussion that could attract government censors or result in budgetary penalties, as some of the laws and bills provide. If educators who raise complex issues related to race, gender, or history face serious legal, financial, or reputational consequences—if discussions of, say, the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements become too risky—class instruction will skirt difficult truths and fear will squelch free expression. Even when political leaders merely threaten to introduce these educational gag orders, or when they are introduced but do not become law, they can still send a potent message that educators are being watched and that ideological redlines exist.

The bills that become law will undoubtedly face court challenges. These bills are attempts at ideological exclusion based on hostility to certain content and viewpoints, and their prohibitions are both vague and overbroad, raising obvious First Amendment concerns. They are also likely to violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, in that these bills will foreseeably be enforced disproportionately against educators and trainers of color. Previous litigation surrounding a state law in Arizona—HB 2281, which made the teaching of ethnic studies courses illegal for public and charter schools—offers a preview of how at least some of these bills are likely to be struck down for violating constitutional guarantees of equal protection, free speech, or the right of students to receive information. Still, it is possible that certain laws will survive judicial review, or be narrowed but not invalidated upon review. The Supreme Court, for example, has given governments leeway to impose restrictions on which ideas they will fund when training public employees. Many of the bills include language that purports to keep them within the technical limits of constitutionality, giving friendly courts potential cover to uphold them.

Even if such laws are struck down, the process may take years, by which point substantial damage to our educational system will already have been done. Schools, educators, and even students will have received and internalized the legislators’ message that they could face disfavor and punishment from the government for espousing certain ideas in the classroom. As Emerson Sykes, senior staff attorney at the ACLU, warns: “The courts alone will not save us. This is really a social and political issue.”17Interview with Emerson Sykes, Staff Attorney – ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, June 22, 2021.

Section I: From Presidential Rhetoric to Republican Policy

Battles over education in the U.S. are often a proxy for broader societal debates and anxieties, and in recent years, a wide-ranging public debate has unfolded surrounding free speech in schools and universities, and perceived tensions with efforts to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion. PEN America has produced three reports on these issues on college campuses, detailing the tensions that have sometimes emerged between calls for greater racial, sexual, and gender equity and traditional notions of free speech and academic freedom, and articulating how schools and universities can and must reconcile these tensions in order to remain open and equitable spaces of learning and debate.18For PEN America’s previous work on how academic institutions can responsibly address the intersections between freedom of speech and diversity, equity, and inclusion, see “Chasm in the Classroom; Campus Free Speech in a Divided America,” PEN America, April 2, 2019, pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/2019-PEN-Chasm-in-the-Classroom-04.25.pdf; “And Campus for All; Diversity, Inclusion, and Freedom of Speech at U.S. Universities,” PEN America, October 17, 2016, pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/PEN_campus_report_06.15.2017.pdf; “Wrong Answer: How Good Faith Attempts to Address Free Speech and Anti-Semitism on Campus Could Backfire,” PEN America, November 7, 2017, pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2017-wrong-answer_11.9.pdf; PEN America Campus Free Speech Guide, campusfreespeechguide.pen.org/about/ There is a direct connection between these dynamics on campuses and those which have now spilled over into schools, workplaces, and school board meetings. But it is also an extension of a longstanding debate focused particularly on the area of social studies, which shapes students’ understanding of the country’s history and culture. Battles over social studies curricula are so long-standing that some experts call them the “social studies wars.”19Kelly Field, The Hechinger Report, “Can critical race theory and patriotism coexist in classrooms?” NBC News, May 28, 2021, nbcnews.com/news/us-news/can-critical-race-theory-patriotism-coexist-classrooms-n1268824; see also Ronald W. Evans, “The Social Studies Wars, Now and Then,” National Council for the Social Studies, Theory & Research in Social Education, Research and Practice, September 2006, socialstudies.org/system/files/publications/articles/se_700506317.pdf; Seeking a Truce in the Civics and History Wars: Is ‘Educating for American Democracy the Answer?, Thomas B. Fordham Institute, June 28, 2021, fordhaminstitute.org/national/events/seeking-truce-civics-history-wars-educating-american-democracy-answer (“Like the cicadas now infesting the mid-Atlantic, debates over how to present American history and civics to our children come around with striking regularity.”) In the past several years, these debates over education, and social studies in particular have been subsumed by broader political trends, largely related to the illiberal inclinations of former President Trump–and the significant segments of the Republican party that follow his lead—seeking to exert new power or execute threats against schools, colleges and universities, in an effort to stifle and suppress their perceived progressive leanings.

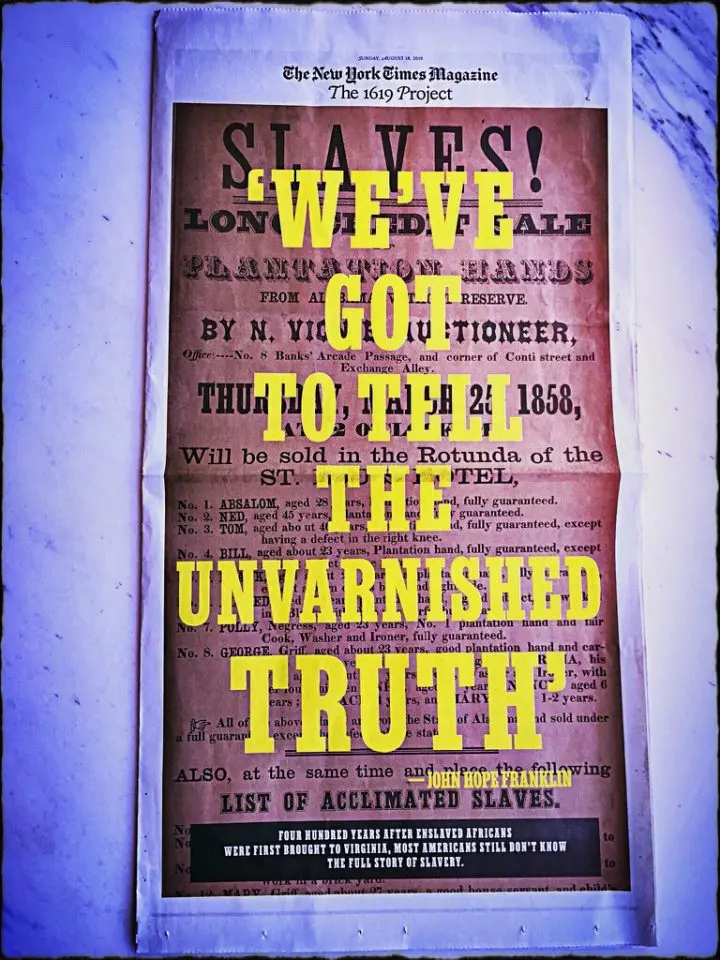

A major flashpoint for these battles occurred in August 2019, with the release of The New York Times’ 1619 Project and the ensuing backlash. It took less than a year for Republican legislators to go from criticizing the project to trying to censor it legislatively: In June 2020, Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas introduced the Saving American History Act in the U.S. Senate, with the goal of blocking federal funds to any school using the project.20S.4292, “Saving American History Act of 2020,” cotton.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/200723%20Saving%20American%20History%20Act.pdf

The summer of 2020 also saw mass Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. This public reckoning with racism led many American institutions in various fields to adopt new curricula, training, and commitments to confront and dismantle racism. These have, in turn, become the focus of pointed ideological disagreement. Kimberlé Crenshaw, the Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law at Columbia Law School and an original architect of critical race theory, noted in an interview with The New Yorker that the large number of “corporations and opinion-shaping institutions” that made “statements about structural racism” in the summer of 2020 meant that “the line of scrimmage has moved.” She characterized the conservative outcry against this shift as “a post-George Floyd backlash.”21Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “How a Conservative Activist Invented the Conflict Over Critical Race Theory,” New Yorker, June 18, 2021, newyorker.com/news/annals-of-inquiry/how-a-conservative-activist-invented-the-conflict-over-critical-race-theory. Similarly, Jin Hee Lee, a senior deputy director of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, argued in a July 2021 interview that “it is no coincidence” that this backlash has come “on the heels of what is maybe the greatest civil rights moment in our history, when there was such a focus on systemic racism and anti-Black racism.”22Maggie Severns, “‘People are scared’: Democrats lose ground on school equity plans,” Politico, July 26, 2021, politico.com/news/2021/07/26/democrats-school-critical-race-theory-500729

What is the 1619 Project?

The 1619 Project is an initiative, led by New York Times journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, to explore the impact of slavery on U.S. history and modern life. In August 2019 The New York Times Magazine published a special issue “containing essays on different aspects of contemporary American life, from mass incarceration to rush-hour traffic, that have their roots in slavery and its aftermath.” The Times partnered with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture to create a visual history of slavery in the United States.23Jake Silverstein, “Why We Published The 1619 Project,” The New York Times, December 20, 2019, nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/20/magazine/1619-intro.html; Mary Elliott and Jazmine Hughes, “Four hundred years after enslaved Africans were first brough to Virginia, most Americans still don’t know the full story of slavery,” The New York Times Magazine, August 18, 2019, nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/history-slavery-smithsonian.html In addition, more than a dozen original literary works were commissioned from contemporary Black writers to “bring to life key moments in American history.”24Jake Silverstein, “Why We Published The 1619 Project,” The New York Times, December 20, 2019, nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/20/magazine/1619-intro.html The project asked readers to imagine that 1619, the year enslaved people were first brought to North America, was “our nation’s birth year. Doing so,” it posited, “requires us to place the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country.”25“The 1619 Project,” The New York Times Magazine, nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html; Jake Silverstein, “Why We Published The 1619 Project,” The New York Times, December 20, 2019, nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/20/magazine/1619-intro.html The Times selected the Pulitzer Center, which runs fellowships and grants for journalists and develops curricula based on journalism, to produce a companion curriculum.26Jeff Barrus, “Pulitzer Center Named Education Partner for The New York Times Magazine’s ‘The 1619 Project’,” The Pulitzer Center, August 14, 2019, pulitzercenter.org/blog/pulitzer-center-named-education-partner-new-york-times-magazines-1619-project. The Pulitzer Center is not affiliated with Columbia University’s Pulitzer Prizes, it was endowed by the wife of Joseph Pulitzer, Jr. the grandson of Joseph Pulitzer who founded Columbia’s journalism school and endowed the prizes which bear his name. See “About the Pulitzer Center,” pulitzercenter.org/about/our-mission-and-model, “Emily Raugh Pulitzer, President of the Board,” pulitzercenter.org/people/emily-rauh-pulitzer, “Emily Rauh Is Married To Joseph Pulitzer Jr.,” The New York Times, July 1, 1973, nytimes.com/1973/07/01/archives/emily-rauh-is-married-to-joseph-pulitzer-jr.html.

The Project received significant praise from a range of historians, professors, and teachers, who highlighted how it filled an important gap in high school and college history curricula. “Taken together, the issue is an attempt to guide readers not just toward a richer understanding of today’s racial dilemmas, but to tell them the truth,” wrote Alexandria Neason for Columbia Journalism Review, “For many, it may be the first time they’ve heard it.”27Alexandria Neason, “The 1619 Project and the stories we tell about slavery,” Columbia Journalism Review, August 15, 2019, cjr.org/analysis/the-1619-project-nytimes.php Christopher Span, a history of education professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, told Forbes that “’The 1619 Project’ should be added to every undergraduate course surveying American history,” and that, in centralizing “the longstanding role race, racism, and slavery played in the making of this nation… [it] affords opportunities for healing and reconciliation.”28Marybeth Gasman, “What History Professors Really Think About ‘The 1619 Project’,” Forbes, June 3, 2021, forbes.com/sites/marybethgasman/2021/06/03/what-history-professors-really-think-about-the-1619-project/?sh=344084ee7a15 In May 2020, Hannah-Jones was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for the Project.29“Nikole Hannah-Jones Wins Pulitzer Prize for 1619 Project,” The Pulitzer Center, May 4, 2020, pulitzercenter.org/blog/nikole-hannah-jones-wins-pulitzer-prize-1619-project

The 1619 Project has also not been free from criticism, and critics have not just come from the right. The most significant critique came on December 4, 2019, when five prominent liberal American history professors including Princeton University’s Sean Wilentz argued in a letter to the Times that the project misrepresented several matters of fact—including the assertion that the founders were motivated to declare independence from Britain in order to maintain the institution of slavery—and that these errors “suggest a displacement of historical understanding by ideology.”30“We Respond to the Historians Who Critiqued The 1619 Project,” The New York Times Magazine, December 20, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/12/20/magazine/we-respond-to-the-historians-who-critiqued-the-1619-project.html (“Raising profound, unsettling questions about slavery and the nation’s past and present, as The 1619 Project does, is a praiseworthy and urgent public service.”); “Twelve Scholars Critique The 1619 Project and the New York Times Magazine Editor Responds,” History News Network, January 26, 2020, historynewsnetwork.org/article/174140 (“None of us have any disagreement with the need for Americans, as they consider their history, to understand that the past is populated by sinners as well as saints, by horrors as well as honors, and that is particularly true of the scarred legacy of slavery.”); Bret Stephens, “The 1619 Chronicles,” The New York Times, October 9, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/10/09/opinion/nyt-1619-project-criticisms.html (“in a point missed by many of The 1619 Project’s critics, it does not reject American values.”); Steven Mintz, “The 1619 Project and Uses and Abuses of History,” Inside Higher Ed, October 28, 2020, insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/1619-project-and-uses-and-abuses-history. The Times responded that all of their claims were grounded in the historical record.31“We Respond to the Historians Who Critiqued The 1619 Project,” The New York Times Magazine, December 20, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/12/20/magazine/we-respond-to-the-historians-who-critiqued-the-1619-project.html. The Times did, however, later qualify one of the Project’s claims in response to criticism, changing one passage to clarify that protecting slavery was “a primary motivation for some of the colonists,” as opposed to all, in declaring independence.32Jake Silverstein, “An Update to The 1619 Project,” The New York Times, March 11, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/03/11/magazine/an-update-to-the-1619-project.html

Journalist Adam Serwer argued in The Atlantic that the disagreement between The 1619 Project writers and critical historians was rooted in a broader dispute over America’s realization of—and commitment to—its founding ideals, writing:

The clash between the Times authors and their historian critics represents a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society. Was America founded as a slavocracy, and are current racial inequities the natural outgrowth of that? Or was America conceived in liberty, a nation haltingly redeeming itself through its founding principles? These are not simple questions to answer, because the nation’s pro-slavery and anti-slavery tendencies are so closely intertwined. The [December 4] letter is rooted in a vision of American history as a slow, uncertain march toward a more perfect union. The 1619 Project, and Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay in particular, offer a darker vision of the nation, in which Americans have made less progress than they think, and in which black people continue to struggle indefinitely for rights they may never fully realize.33Adam Serwer, “The Fight Over The 1619 Project Is Not About the Facts,” The Atlantic, December 23, 2019, theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/12/historians-clash-1619-project/604093/

Jonathan Zimmerman, an educational historian at the University of Pennsylvania, has said that teaching “The 1619 Project” alongside other interpretations of history “represents a huge opportunity to teach students what history actually *is*: an act of interpretation.”34Marybeth Gasman, “What History Professors Really Think About ‘The 1619 Project’,” Forbes, June 3, 2021, forbes.com/sites/marybethgasman/2021/06/03/what-history-professors-really-think-about-the-1619-project/?sh=344084ee7a15 Similarly, Alan J. Singer, professor of teaching, learning and technology and the director of social studies education at Hofstra University, explains that though he disagrees with some points of emphasis in the Project, it is still “vitally important” considering that the U.S. has no national history curriculum. As he states, “Unless Americans understand the role slavery and racism played in the past and in the present, this country will never be able to create a more just and equitable future.”35Alan J. Singer, “Defending the 1619 Project in the Context of History Education Today,” History News Network, December 20, 2020, historynewsnetwork.org/article/178586

As American institutions—including educational institutions—have increasingly committed to anti-racism and diversity training programs, some commentators have expressed concern that these programs may enforce singular narratives and interpretations of history and culture that cannot be contested without the challenger being labeled as out of touch, insensitive, or worse. This includes programming that purportedly draws on critical race theory. “Critical race theory as it developed in the academy is intellectually rich, but some of the ways it’s been adapted by workplace diversity trainers and education consultants seem risible,” Michelle Goldberg wrote in The New York Times in March. (She nonetheless went on to note that the right-wing effort to ban CRT was “a far more direct threat to free speech than what’s often called cancel culture.”)36Michelle Goldberg, “The Social Justice Purge at Idaho Colleges,” The New York Times, March 26, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/03/26/opinion/free-speech-idaho.html Others have questioned whether American schools’ commitment to eradicating racism, as put into practice, may chill the speech of students and teachers who feel that they cannot express thoughtful disagreement with their school’s instruction without repercussions.37See e.g. Michael Powell, “New York’s Private Schools Tackle White Privilege. It Has Not Been Easy,” The New York Times, August 27, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/08/27/us/new-york-private-schools-racism.html

PEN America takes such concerns – and their manifest chilling effect – very seriously: Our Campus Free Speech Guide, for example, includes advice to administrators, educators, and students alike on how to ensure that colleges’ and universities’ embrace of diversity is underpinned by a commitment to freedom of speech and strong protections for academic freedom. It is essential that American institutions take steps to combat racism without steamrolling dissent or smothering robust debate.

But such nuanced deliberation is often at odds with political imperatives. Here, the question of how to most thoughtfully promote anti-racism in public schools and in workplace trainings has been overtaken and supplanted by a political narrative against “Critical Race Theory” that has been embraced by Republican legislators as a partisan rallying cry. We can clearly trace the origins of this narrative. Beginning in 2020, President Trump seized upon ”diversity trainings” and anti-racism teachings as a convenient bogey to rally supporters against. In turn, the Trump Administration’s efforts directly spurred and shaped today’s state-level legislative efforts to impose ideological blacklists on educators and trainers. These efforts, in the name of saving Americans from anti-racist “indoctrination,” represent a substantial and unwarranted government intrusion into Americans’ free speech and academic freedom.

Trump Executive Order

The majority of the state bills reviewed in this report draw extensively on an executive order issued by former President Donald Trump shortly before he left office. In September 2020, the Trump administration’s Office of Management and Budget released a prelude of sorts—a memo from OMB director Russell Vought that condemned critical race theory and directed federal agencies to “desist from using taxpayer dollars to fund . . . divisive, un-American propaganda training sessions.”38Agencies were directed to “identify all contracts or other agency spending related to any training on “critical race theory,” “white privilege,” or “any other training or propaganda effort that teaches or suggests either (1) that the United States is an inherently racist or evil country or (2) that any race or ethnicity is inherently racist or evil.” Memo from Russell Vought, Director, OMB (Sept. 4, 2020), M-20-34, whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/M-20-34.pdf. A couple of weeks later, in a speech at the National Archives, Trump claimed that “the left has warped, distorted, and defiled the American story with deceptions, falsehoods, and lies,“ identifying certain efforts by name as especially pernicious: “Critical race theory, The 1619 Project, and the crusade against American history is toxic propaganda, ideological poison that, if not removed, will dissolve the civic bonds that tie us together. It will destroy our country.”39President Trump Remarks at White House History Conference, Sept. 17, 2020, c-span.org/video/?475934-1/president-trump-announces-1776-commission-restore-patriotic-education-nations-schools; Kathryn Watson and Grace Segers, “Trump blasts 1619 Project on role of Black Americans and proposes his own ‘1776 commission’,” CBS News, September 18, 2020, cbsnews.com/news/trump-1619-project-1776-commission/ To fight back, he announced the formation of a “1776 Commission” to promote “patriotic education.”40Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder, “Trump Says He Will Create Commission to Promote ‘Patriotic Education,” US News, September 17, 2020, usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2020-09-17/trump-says-he-will-create-commission-to-promote-patriotic-education

Trump’s “Divisive Concepts”

Sec. 2. Definitions. For the purposes of this order, the phrase:

(a) “Divisive concepts” means the concepts that

(1) one race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex;

(2) the United States is fundamentally racist or sexist;

(3) an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously;

(4) an individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment solely or partly because of his or her race or sex;

(5) members of one race or sex cannot and should not attempt to treat others without respect to race or sex;

(6) an individual’s moral character is necessarily determined by his or her race or sex;

(7) an individual, by virtue of his or her race or sex, bears responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race or sex;

(8) any individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex; or

(9) meritocracy or traits such as a hard work ethic are racist or sexist, or were created by a particular race to oppress another race.

The term “divisive concepts” also includes any other form of race or sex stereotyping or any other form of race or sex scapegoating.

(b) “Race or sex stereotyping” means ascribing character traits, values, moral and ethical codes, privileges, status, or beliefs to a race or sex, or to an individual because of his or her race or sex.

(c) “Race or sex scapegoating” means assigning fault, blame, or bias to a race or sex, or to members of a race or sex because of their race or sex. It similarly encompasses any claim that, consciously or unconsciously, and by virtue of his or her race or sex, members of any race are inherently racist or are inherently inclined to oppress others, or that members of a sex are inherently sexist or inclined to oppress others.

On September 22, 2020, Trump issued his Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotypes. It claimed that “many people are pushing a . . . vision of America that is grounded in hierarchies based on collective social and political identities rather than in the inherent and equal dignity of every person as an individual.” The EO decried this vision as a “destructive,” “malign” ideology that “threatens to infect core institutions of our country.”41Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping, September 22, 2020, trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-combating-race-sex-stereotyping/ The executive order adopted sweeping rules that defined particular “divisive concepts” dealing with race and sex in America, such as the argument that “the United States is fundamentally a racist country” (see sidebar).

The EO went on to prohibit the expression of these concepts from any federal employee training, as well as from any training that any institution that contracted with the federal government could offer its own employees. The EO also prohibited the US military from offering training or courses in any such concepts.42At Section 3. In January 2021, in response to questions from Republican federal legislators, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Milley, would give remarks stating that the military does not teach Critical Race Theory, but defending the military’s ability to offer classes on subjects such as “white rage,” saying that it was crucial for military members “to be open-minded and widely read.” See “Gen. Milley defends military studies of critical race theory: ‘I want to understand white rage,’” NBC News, June 23, 2021, nbcnews.com/video/gen-milley-defends-studying-critical-race-theory-in-the-military-at-house-hearing-115349061782; see also Jeff McCausland, “General Milley, critical race theory and why GOP’s ‘woke’ military concerns miss the mark,” NBC News, June 28, 2021, nbcnews.com/think/opinion/general-milley-critical-race-theory-why-gop-s-woke-military-ncna1272558

The EO further directed all federal agencies to compile a list of grants that could be conditioned on prohibiting the concepts, set up a hotline for reporting violations, and instructed the Office of Personnel Management to adopt rules that would require supervisors to “pursue a performance-based adverse proceeding” against any employee who approved training that contained these blacklisted ideas.43Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping, September 22, 2020, trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-combating-race-sex-stereotyping/. Although not as extensive or as extreme in consequence, the Trump EO brings to mind Truman’s Executive Order 9835, which set up loyalty boards throughout the federal government and required people who failed to be fired. Executive Order 9835, trumanlibrary.gov/library/executive-orders/9835/executive-order-9835; see also Dan Kaufman, “The Real Legacy of a Demagogue,” The New Republic, October 2, 2020, newrepublic.com/article/159568/real-legacy-demagogue-joseph-mccarthy-donald-trump-book-review. The order also threatened to strip federal funding from institutions that required training that included these concepts.

Since almost all state universities have contracts with the federal government, university officials across the country scrambled to understand how the EO would apply to them, especially for Title IX training on sex discrimination or other training on gender and racial inequality in academia. At least two educational institutions, the University of Iowa and John A. Logan College in Illinois, quickly moved to suspend diversity-related training and events in the wake of the order.44Colleen Flaherty, “Colleges cancel diversity programs in response to Trump order,” Inside Higher Ed, October 7, 2020, insidehighered.com/news/2020/10/07/colleges-cancel-diversity-programs-response-trump-order

Where did the ideas behind this EO come from? In a general sense, this EO, issued late in the Trump presidency and just before the 2020 election, reflected the broader political strategy that, in 2019, The Washington Post called “Trump’s combustible formula of white identity politics.”45Michael Sherer, “White identity politics drives Trump, and the Republican Party under him,” The Washington Post, July 16, 2019, washingtonpost.com/politics/white-identity-politics-drives-trump-and-the-republican-party-under-him/2019/07/16/a5ff5710-a733-11e9-a3a6-ab670962db05_story.html More proximately, according to The New York Times, “Mr. Trump’s focus on diversity training seems to have originated with an interview he saw on Fox News, in which Christopher F. Rufo, a conservative scholar at the Discovery Institute, told Tucker Carlson of the ’cult indoctrination’ of ’critical race theory’ programs in the government.”46Hailey Fuchs, “Trump Attack on Diversity Training Has a Quick and Chilling Effect,” The New York Times, Oct. 13, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/10/13/us/politics/trump-diversity-training-race.html. Rufo himself has been clear that his goal is not to attack critical race theory as a concept in academia, but rather to appropriate the phrase as an umbrella term to demonize a range of vaguely related activities that he believes conservatives should find objectionable and can be motivated to mobilize against. As described in a profile of Rufo by The New Yorker’s Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “As Rufo eventually came to see it, conservatives engaged in the culture war had been fighting against the same progressive racial ideology since late in the Obama years, without ever being able to describe it effectively.” Rufo told the magazine, “We’ve needed new language for these issues,” and “‘critical race theory’ is the perfect villain.”47Benjamin Wallace-Wells, “How a Conservative Activist Invented the Conflict Over Critical Race Theory,” New Yorker, June 18, 2021, newyorker.com/news/annals-of-inquiry/how-a-conservative-activist-invented-the-conflict-over-critical-race-theory. Rufo had previously explained on Twitter, “We will eventually turn [critical race theory] toxic, as we put all of the various cultural insanities under that brand category…. The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory.’ We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.’”48@realchrisrufo, March 15, 2021, twitter.com/realchrisrufo/status/1371541044592996352; see also Christopher Rufo, “Critical Race Theory Briefing Book,” christopherrufo.com/crt-briefing-book/ (purporting to offer tools to “win the language war” around critical race theory).

Patricia Williams, the Director of Law, Technology, and Ethics at Northeastern University and a leading scholar of Critical Race Theory, has labeled this deliberate mischaracterization of Critical Race Theory as “definitional theft.”49Jelani Cobb, “The man behind critical race theory,” New Yorker, September 13, 2021, newyorker.com/magazine/2021/09/20/the-man-behind-critical-race-theory Kimberlé Crenshaw has argued that this misrepresentation allows opponents of CRT to “take the name, fill it with meaning, and create this hysteria” which is politically useful.50Jon Wiener, “The predictable backlash to Critical Race Theory: A Q&A with Kimberle Crenshaw,” The Nation, July 5, 2021, thenation.com/article/politics/critical-race-kimberle-crenshaw/

Rufo’s efforts have been largely successful in positioning the term “critical race theory” into a political label to be appended onto any instruction that certain conservatives find objectionable. Rufo does not mince words in his attacks: “CRT-based programs are often hateful, divisive, and filled with falsehoods; they traffic in racial stereotypes, collective guilt, racial segregation, and race-based harassment.”51Christopher Rufo, “Critical Race Fragility,” City Journal, March 2, 2021, city-journal.org/the-left-wont-debate-critical-race-theory. He depicts CRT as an existential threat to the country. As he wrote in a paper for the Heritage Foundation, “Critical race theory seeks to undermine the foundations of American society and replace the constitutional system with a near-totalitarian ‘antiracist’ bureaucracy.”52Christopher Rufo, “Critical Race Theory Would Not Solve Racial Inequality: It Would Deepen It,” The Heritage Foundation, March 23, 2021), heritage.org/progressivism/report/critical-race-theory-would-not-solve-racial-inequality-it-would-deepen-it.

The Wall Street Journal reported that the day after Rufo’s September 1 segment with Carlson, Trump’s White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows called him, and two days after that, Trump’s Office of Management and Budget issued its memo.53Paul Kiernan, “Conservative Activist Grabbed Trump’s Eye on Diversity Training,” The Wall Street Journal, October 9, 2020, wsj.com/articles/conservative-activist-grabbed-trumps-eye-on-diversity-training-11602242287 Trump’s speech at the National Archives came 13 days later, and his executive order came five days after that—exactly three weeks after Rufo’s Fox appearance. Since Trump’s executive order was released, Rufo told a reporter, he has provided his analysis to a half-dozen state legislatures, the United States House of Representatives, and the United States Senate.54Adam Harris, “The GOP’s ‘Critical Race Theory’ Obsession,” The Atlantic, May 7, 2021, theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2021/05/gops-critical-race-theory-fixation-explained/618828/; In December 2020, Rufo participated in webinars with the Heritage Foundation55“Against Critical Theory’s Onslaught: Reclaiming Education and the American Dream,” American Legislative Exchange Council, December 8, 2020 alec.org/article/reclaiming-education-and-the-american-dream-against-critical-theorys-onslaught/ and with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), the organization known for producing and pushing conservative model bills for state legislatures.56Ed Pilkington, “Rightwing ‘bill mill’ accused of sowing racist and white supremacist policies,” The Guardian, December 3, 2019, theguardian.com/us-news/2019/dec/02/alec-white-supremacy-conservatives-racism; Tyler Kingkade, Brandy Zadrozny and Ben Collins , “Critical race theory battle invades school boards—with help from conservative groups,” NBC News, June 15, 2021, nbcnews.com/news/us-news/critical-race-theory-invades-school-boards-help-conservative-groups-n1270794

Trump’s executive order met with widespread condemnation, including from the higher-education and business sectors. One hundred sixty trade associations and nonprofits, including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, sent a letter to President Trump a few weeks after the EO’s adoption, asking him to withdraw it because it would “create confusion and uncertainty, lead to non-meritorious investigations, and hinder the ability of employers to implement critical programs to promote diversity and combat discrimination in the workplace.”57Letter to President Trump from 160 trade associations and non-profits, October 15, 2020, image.uschamber.com/lib/fe3911727164047d731673/m/5/b5c62775-5376-4f8d-9384-35b76ce39682.pdf More than a hundred civil rights groups denounced the order. The Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law declared it “a blatant effort to perpetuate and codify a deeply flawed and skewed version of American history. It promotes a particular vision of history that glorifies a past rooted in white supremacy while silencing the viewpoints and experiences of all who have been victimized by individual and structural inequalities—a kind of dangerous propaganda or thought-policing comparable only to authoritarian regimes.”58Don Owens, “Civil Rights Groups Condemn White House Move to Censor Race and Gender Equity,” Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, October 7, 2020, lawyerscommittee.org/civil-rights-groups-condemn-white-house-move-to-censor-race-and-gender-equity/

A federal judge partially blocked the order on constitutional grounds in December 2020, and President Biden repealed it on his first day in office.59The details of the injunction are addressed below. Jessica Guynn, “Trump diversity executive order: Civil rights group sues federal government for access to documents” USA Today, May 2, 2021, usatoday.com/story/money/2021/04/30/trump-diversity-executive-order-naacp-lawsuit-biden-racism/4893931001/ Even so, Trump’s executive order was instrumental in galvanizing the broad effort that gained momentum in 2021 to circumscribe discussions of race, racism, and gender by prohibiting the teaching of certain ideas.

What Is Critical Race Theory?

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is an intellectual framework used to analyze, explain, and critique racial disparities. It originated in the 1970s in the aftermath of the civil rights movement as an interpretation of why progress toward racial equality had seemingly stalled.60Critical Race Theory’s origins lie with Prof. Derrick Bell’s article “Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma,” Harvard Law Review, Volume 93, No. 3, 1980, pages 518–533, jstor.org/stable/1340546; see Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, “Critical Race Theory: Past, Present, and Future,” Current Legal Problems, Volume 51, Issue 1, 1998, pages 467–491, doi.org/10.1093/clp/51.1.467. academic.oup.com/clp/article-abstract/51/1/467/366105?redirectedFrom=PDF Its earliest proponents included prominent scholars such as Derrick Bell, a civil rights activist and Harvard Law School’s first tenured Black professor, and Mari Matsuda, the first tenured Asian-American law professor in the United States.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, one of the leaders and founders of CRT, has said that the theory starts with the contention that “the triumph of formal equality did not signify the end of racism,” then attempts to explain why and identify remedies.61Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, “Race to the Bottom,” The Baffler, June 2017, thebaffler.com/salvos/race-to-bottom-crenshaw. See also: “Critical Legal Studies Movement” Harvard University Law School, Berkman Klein Center, The Bridge, cyber.harvard.edu/bridge/CriticalTheory/critical2.htm; “Critical Race Theory,” Harvard University Law School, Berkman Klein Center, The Bridge, cyber.harvard.edu/bridge/CriticalTheory/critical4.htm. Over time this foundational observation has grown beyond its legal origins to influence other social science, humanities, and professional fields, such as sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s theory of “color-blind racism” as a model to explain the existence of “racism without racists.”62Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists; Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America, (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2018); Samuel Hoadley-Brill, “Critical Race Theory’s Opponents Are Sure It’s Bad. Whatever It Is,” The Washington Post, July 2, 2021, washingtonpost.com/outlook/critical-race-theory-law-systemic-racism/2021/07/02/6abe7590-d9f5-11eb-8fb8-aea56b785b00_story.html Scholars working in this tradition generally contend that U.S. legal and societal structures operate in ways that solidify racial inequality, even if these laws and institutions, and the individuals who populate them, do not consciously embrace racist ideas.

In state after state, primary and secondary teachers and pre-service teacher educators have strongly attested that, as an intellectual framework, CRT is not taught in elementary, middle or high schools, insisting that critics have conflated the academic theory taught in colleges (and law schools in particular) with other diversity initiatives.63David Childs, “Is Anyone Actually Teaching Critical Race Theory in their Classroom? Why are States Banning It?” Democracy & Me, June 23, 2021, democracyandme.org/is-anyone-actually-teaching-critical-race-theory-in-their-classroom-why-are-states-banning-it/; Rashawn Ray and Alexandra Gibbons, “Why are states banning critical race theory?” Brookings Institution, July 2021, brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2021/07/02/why-are-states-banning-critical-race-theory/; Caitlin O’Kane, “Head of teachers union says critical race theory isn’t taught in schools, vows to defend ‘honest history’,” CBS News, July 8, 2021, cbsnews.com/news/critical-race-theory-teachers-union-honest-history/; Phil McCausland, “Teaching critical race theory isn’t happening in classrooms, teachers say in survey,” NBC News, July 1, 2021, nbcnews.com/news/us-news/teaching-critical-race-theory-isn-t-happening-classrooms-teachers-say-n1272945; “EXPLAINED: The Truth About Critical Race Theory and How It Shows Up in Your Child’s Classroom,” Education Post, May 5, 2021, educationpost.org/explained-the-truth-about-critical-race-theory-and-how-it-shows-up-in-your-childs-classroom/ Yet discussion of what does or doesn’t constitute CRT is in many ways a distraction from the pressing issues at stake in statehouses across the country. As Rufo’s comments demonstrate, and as PEN America’s review of the 54 educational gag order bills reveals, this “anti-CRT” legislation is not principally intended to prohibit the academic study of CRT itself, and it would ban and punish a far broader set of inquiries and ideas from examination and discussion in American schools and universities.

Section II: State-Level Legislative Efforts to Impose Educational Gag Orders

Beginning in January 2021, various state legislators took up the charge initiated by the Trump Administration, continuing the campaign against curricula and ideas labeled “CRT,” The 1619 Project, and diversity training in the workplace. While many of these bills were clearly inspired by the Trump executive order, together this raft of bills attempts to impose a far more sweeping and society-wide change. Specifically, while the Trump EO primarily applied to government trainers and contractors as well as military personnel, the great majority of the state-level bills would extend these prohibitions to all state schools and/or colleges and universities.

Over time, the depiction of critical race theory by Republican officials and some politically conservative media has evolved into exactly the scapegoat envisioned by Rufo. Just as he’d hoped, parents are now pressuring school boards to ban books and remove elements of curriculum they object to under the inaccurate guise that it is ‘Critical Race Theory.’64Tyler Kingkade, Brady Zadrozny, and Ben Collins, “Critical race theory battle invades school boards— with help from conservative groups”, NBC News, June 15, 2021, nbcnews.com/news/us-news/critical-race-theory-invades-school-boards-help-conservative-groups-n1270794 Lawmakers, meanwhile, have weaponized these beliefs with actions. The term “Critical Race Theory” appeared by name in only one of 15 educational gag order bills introduced in January and February but was named in five of 21 bills introduced from March to May.

In January, legislators in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Iowa introduced bills that would have explicitly barred the expenditure of public funds on curricula derived from The New York Times’ 1619 Project,65Arkansas HB 1231, legiscan.com/AR/text/HB1231/2021; Mississippi SB 2538, billstatus.ls.state.ms.us/documents/2021/html/SB/2500-2599/SB2538IN.htm; Iowa, HF 222, legiscan.com/IA/text/HF222/id/2260602 based in part or whole on Senator Tom Cotton’s Saving American History Act, introduced in July 2020.66Saving American History Act of 2020, S.4292, congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/4292/text A separate Arkansas bill (HB 1218) proposed a prohibition on any public school or college allowing a “course, class, event, or activity” that “promotes division between, resentment of, or social justice for” a race, gender, political affiliation, social class, or particular class of people.”67Arkansas HB 1218, arkleg.state.ar.us/Bills/FTPDocument?path=%2FBills%2F2021R%2FPublic%2FHB1218.pdf A South Dakota bill (HB 1157) with very similar provisions quickly followed.68South Dakota HB 1157, mylrc.sdlegislature.gov/api/Documents/214785.pdf

That same month, South Dakota’s HB 1158 proposed to ban The 1619 Project as well but listed it as an example of a broader prohibition on schools using materials “associated with efforts to reframe this country’s history in a way that promotes racial divisiveness and displaces historical understanding with ideology.”69South Dakota HB 1158, mylrc.sdlegislature.gov/api/Documents/214787.pdf In Missouri, HB 952 sought to ban “any curriculum implementing critical race theory” and provided an explicit list of examples, including The 1619 Project as well as the Learning for Justice Curriculum, We Stories, programs of Educational Equity Consultants, BLM at School, Teaching for Change, and the Zinn Education Project.70Missouri HB 952, house.mo.gov/billtracking/bills211/hlrbillspdf/2087H.02C.pdf

All seven of these bills died or were withdrawn in the ensuing months. But the crusade to pass educational gag orders continued. In February and March, bills were introduced that focused on barring “divisiveness,” “race and sex stereotyping,” and discussions of “divisive concepts” in schools, colleges, state agencies, and institutions as well as from contractors. State after state mimicked the Trump EO’s list of “divisive concepts,” proposing a range of ways that these concepts could be barred from education and training. Over those two months, bills in this vein were introduced in nine states: Arizona, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Tennessee, West Virginia, Rhode Island, Iowa, Texas, and North Carolina. The trend continued in April, with bills introduced in Arkansas, Louisiana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Idaho—and then in May, in Missouri, South Carolina, Michigan, and Ohio. In June, similar bills appeared in Pennsylvania, Arizona, Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin, along with the pre-filing of bills for 2022 legislative sessions in Alabama and Kentucky. In July and August, Texas legislators filed two sets of sequential, nearly identical bills during two separate special legislative sections.

During the same period, several states took executive actions—including attorney general’s opinions,71Montana Attorney General Opinion Letter, Vol. No. 58, Op. No. 1, at 18, May 27, 2021 dojmt.gov/attorney-general-knudsen-issues-binding-opinion-on-critical-race-theory/ (concluding that “key elements of Critical Race Theory and so-called “antiracism” education and training, when used to classify students or other Montanans by race, violate the Equal Protection Clause, Title VI, Montana’s Individual Dignity Clause, and the MHRA.”). governor’s pledges,72South Dakota Governor Noam signed a “The 1776 Pledge to Save Our Schools,” which seeks to restore “patriotic education” while also attacking critical race theory. Aris Folley, “Noem takes pledge to restore ‘patriotic education’ in schools,” The Hill, May 4, 2021, thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/551799-noem-takes-pledge-to-restore-patriotic-education-in-schools. and state education rules—all borrowing similar language prohibiting “divisive concepts,” “race and sex stereotyping,” “critical race theory,” or The 1619 Project.73Department of Education, State Board of Education, Notice of Change, Rule No. 6A-1.094124, Required Instruction Planning and Reporting, flrules.org/gateway/ruleno.asp?id=6A-1.094124&PDate=6/14/2021&Section=3. Some local school boards adopted the same rhetoric and aims.74“Combating Racist Training in the Military Act of 2021,” S. 968; “Stop CRT Act,” HR 3179. In May, Montana Attorney General Austin Knudsen joined the national debate, issuing a binding resolution that carries the weight of law in the state, holding that teaching CRT and anti-racism programs is discriminatory and violates federal law.75“Attorney General Knudsen Issues Binding Opinion On Critical Race Theory,” Montana Department of Justice, May 27, 2021, dojmt.gov/attorney-general-knudsen-issues-binding-opinion-on-critical-race-theory/

In addition to the Trump EO and the Saving American History Act, another influential template for state-level legislation has been the Partisanship Out of Civics Act, a model bill published in February 2021. This model bill was written by Stanley Kurtz, a conservative commentator and senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, a D.C think tank whose purpose is to “apply the riches of the Judeo-Christian tradition” to American policy.76Notably, Kurtz is also the author of the Goldwater model bill, a model piece of legislation that claims to restore free expression on U.S. college campuses. PEN America examined the Goldwater bill at length in our previous report Wrong Answer, concluding that though the Goldwater model bill possesses strengths, it also outlines an overly punitive system of discipline that may in fact serve to deter peaceful protests. See “Wrong Answer: How Good Faith Attempts to Address Free Speech and Anti-Semitism on Campus Could Backfire,” PEN America, November 7, 2017, pen.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/2017-wrong-answer_11.9.pdf The Partisanship Out of Civics Act banishes the supposedly divisive concepts in the Trump EO from the classroom, prohibits civics teachers from being required to teach “controversial issues of public policy or social affairs,” and, if the topics are taught, requires teachers to “strive to explore such issues from diverse and contending perspectives.”77Stanley Kurtz, “The Partisanship Out of Civics Act,” February 15, 2021, National Association of Scholars, nas.org/blogs/article/the-partisanship-out-of-civics-act. It also prohibits schools from giving “service-learning” credit to students engaging in social or public policy advocacy and from using private funding to obtain curricular materials or teacher training.78Id., Section B, (3)-(5). Eight bills—proposed in Arizona, Ohio, Texas, and South Carolina—bear a partial or direct likeness to this model bill. In North Carolina, SB 700, introduced in April, focuses on mandating that students encounter “balanced political viewpoints” on all subject matter in schools. It bears little resemblance to the Trump-inspired “divisive concepts” or 1619 Project bills; instead, it appears exclusively influenced by Kurtz’s model bill.79North Carolina S.B. 700, ncleg.gov/Sessions/2021/Bills/Senate/PDF/S700v1.pdf

A bill in Tennessee, HB 800, similarly tries to impose ideological controls on education but sticks to gender and sexuality issues. The bill, currently the only one of its kind insofar as our research revealed, proposes to ban any curricular materials that “promote, normalize, support, or address lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) issues or lifestyles.”80Tennessee H.B. 800, capitol.tn.gov/Bills/112/Bill/HB0800.pdf What proponents of HB 800 are “really worried about,” wrote University of Tennessee Knoxville psychology professor Patrick Grzanska, is “that curricula that include the experiences, contributions, and struggles of sexual and gender minorities might actually do exactly what all good education is intended to do. A strong education should expose students to unfamiliar ideas, challenge them to take another’s perspective, reconsider taken-for-granted assumptions, and, ideally, become less inclined to prejudge, dehumanize, or discriminate against those who are different from them.”81Patrick R. Grzanka, “Tennessee lawmakers seek to cancel LGBTQ history and censor education | Opinion,” Tennessean, March 29, 2021, tennessean.com/story/opinion/2021/03/29/tennessee-lawmakers-seek-cancel-lgbtq-history-and-censor-education/7045649002/ Note that Grzanska included another Tennessee bill in this critique—HB 529, which would require parents to be notified before their child is taught a “sexual orientation” or “gender identity” curriculum. While this bill raises many of the same concerns as the 54 bills we evaluate in this report, we did not include curriculum “opt out” bills in this analysis. This lack of inclusion in no way implies that PEN America supports such a bill or considers it to be consistent with the commitments to freedom of expression or to supporting the expression of diverse voices that underlie PEN America’s mission.

In all, 54 educational gag order bills were introduced in 24 states over a nine-month period: 18 remain pending,82As of October 1, 2021. 14 died, four were withdrawn, one was vetoed, and six were pre-filed for 2022. Eleven of these bills were passed into law.

The 54 state-level bills are not carbon copies. They mix and match concepts and wording—taking a phrase from one source, a mechanism from another, and enforcement provisions from another, while often creating one or two new provisions. A minority of the bills style themselves as defending teachers or students from being “compelled” to affirm critical race theory or specific “prohibited” or “divisive” ideas. Even those bills that explicitly claim to defend academic freedom or the First Amendment accomplish the exact opposite, sending the message to instructors and educators that the state intends to police their speech and block consideration of a specific viewpoint.

Targets: Schools, Colleges, and State Institutions

K-12 Schools

Forty-eight bills have applied to K-12 schools, of which nine became law, in Arizona, Idaho, Iowa, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas. Twenty-two are either pending or have been pre-filed for 2022. The nine passed laws include language similar to the Trump executive order on so-called divisive concepts, laying out topics that are forbidden for teaching or training purposes.

Colleges and Universities

Twenty-one bills explicitly apply to colleges and universities. Of these, 16 explicitly impose restrictions on academic courses or curricula, and 10 explicitly address training for college students or employees. Three bills became law, in Oklahoma, Idaho, and Iowa. All three impose prohibitions on training or orientations, while Idaho’s law additionally applies these ideological bans to academic instruction. Twelve such bills, all but two of them explicitly targeting academic teaching, are pending or have been pre-filed for 2022.

State Agencies, Institutions, and/or Contractors

Nineteen bills call for prohibitions on training for or by state agencies, institutions, political subdivisions, and/or contractors. Six of them became law, in Arizona, Arkansas, Iowa, New Hampshire, and Texas. Eight bills are pending or have been pre-filed for 2022. The scope of many of these bills is ambiguous, and it is unclear whether their provisions extend to public colleges and universities and to public schools.

Section III: Critical Race Theory as a Political Bogeyman

Over the past year then, what started as an election-season gambit by President Trump to prohibit “race and sex stereotyping” metamorphosed into a nationwide movement among Republican legislators, governors, pundits, and activists to crush a broad set of ideas and teachings dubbed “critical race theory” and specific curricula they associate with it.