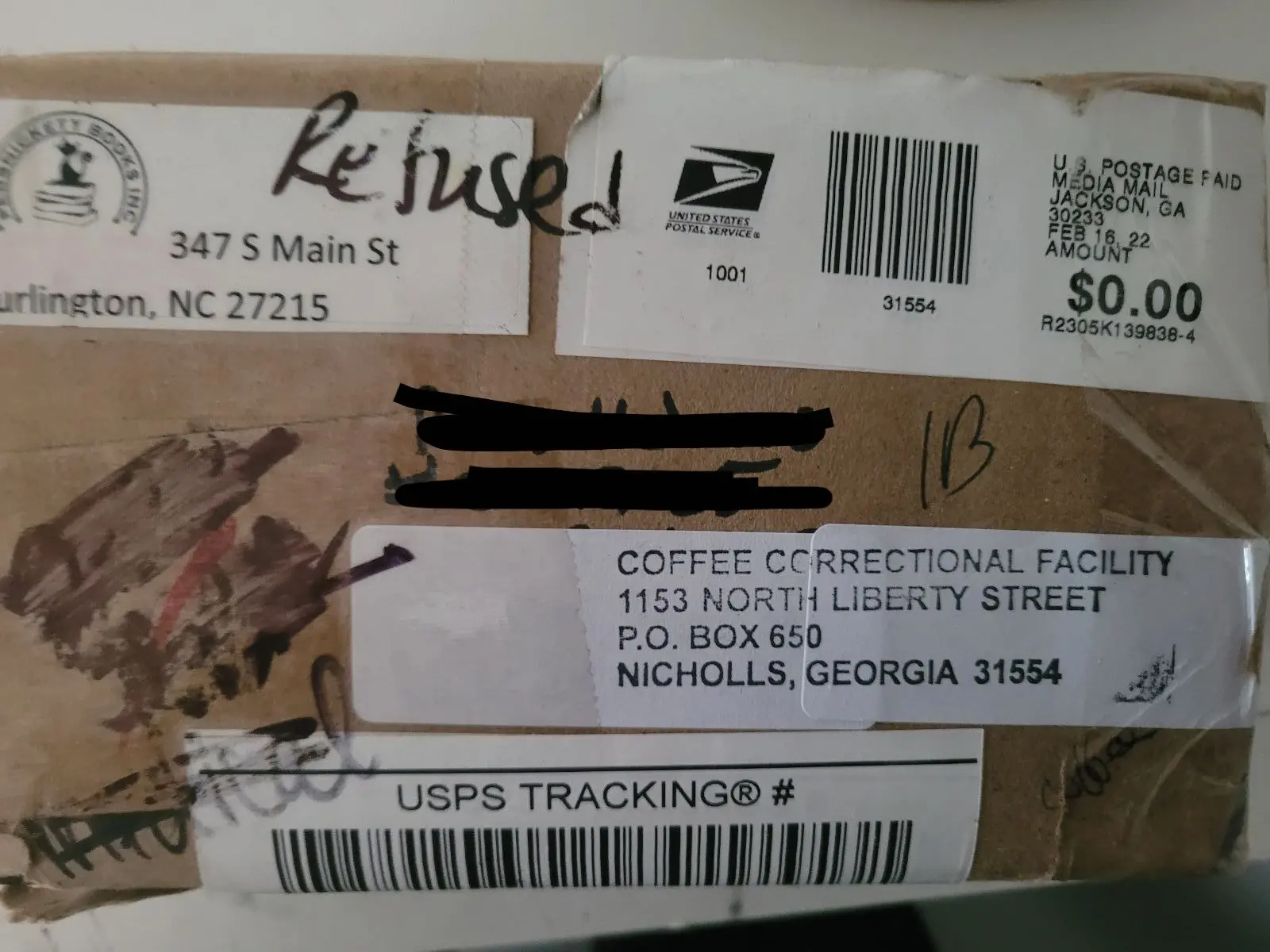

The brown paper package has “Refused” written in black marker across the top. It’s been opened and resealed with packing tape. This package was sent to a person incarcerated in Coffee Correctional in Georgia. It contained two paperback books based on his requests: Lisa Jackson’s Wicked Lies and Orson Scott Card’s Shadow Puppets. This package of books has been censored by the prison. It’s not legal. But, they do it. While many states have banned book lists that limit the books which can be mailed into prisons and jails, the unofficial censorship of the mailroom staff is even more arbitrary.

Working with prison books programs for the last fifteen years, I have seen countless packages of books rejected and returned.

There are innumerable obstacles to sending books to people inside prisons and jails that are legal. Some prisons require prior approval. This paperwork must be submitted, signed, and mailed before receiving the books. Other facilities have rules regarding the number of books or the color of the paper the package is mailed in. There are banned book lists—some of which are public, and some are not. There are bans on the types of books—for example, many states ban blank composition books since prison commissaries sell those and want incarcerated people to purchase them rather than get them for free. There are limits on who counts as an “approved vendor.” Many states are trying to limit “approved vendors” to Amazon only. All of these are legal. It means prison books programs have to meet these guidelines—jumping through the bureaucratic hoops to send reading material to incarcerated people.

General “refused” packages don’t fit any of these, though. These are books that are mailed back because the person in the mailroom who opens the package looks at the books, the name of the person, or the sender and says to themselves, “Nope.” Sometimes, books are already in the prison library and denied. In states with extensive banned books lists, mailroom staff is technically required to check every title that comes into the facility. However, some mailroom staff only select books to check by Black authors. They justify this by pointing out that Black authored books are most regularly censored. The rationale for refusing isn’t universal. On the receiving end, prison books programs can only speculate since there’s no stated reason. There are probably a million reasons.

When the books are rejected, they are mailed back to the prison books program’s partnering bookstore—which has to pay the cost of returning the mail to USPS. So, prison books programs, which are 99% all volunteer-run and largely operate on shoestring budgets garnered by donations from local folx, have to pay twice, and the books don’t get to the person inside. This constantly happens even though prison book programs share information on what different prisons accept and reject in order to try to avoid it. If we didn’t work together, these costs would sink most programs. Refused packages constitute illegal and yet mundane censorship for incarcerated people.

Prison Books programs keep track of refusals and other returns that have no stated reason in order to mount legal challenges. We take photos of the returned packages and keep detailed records of what mailroom staff says are the reasons for the return—if any. We recruit lawyers to write letters to Wardens indicating that we’re not just going to accept a refusal to allow people to read. But, this behavior is pervasive in prison bureaucracies which means lots of money and time. Those are things all-volunteer-run collectives usually have little of. So, on the list of national prison restrictions that prison book programs crowdsource and share, many facilities are marked “Do not send.” The people in those prisons and jails are cut-off from receiving reading materials—the most commonly requested of dictionaries. Dictionaries are most requested because sixty percent of incarcerated people are functionally illiterate1Elizabeth Greenberg, Eric Dunleavy, and Mark Kutner, “Literacy Behind Bars: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy Prison Survey,” U.S. Department of Education, Washington, DC, National Center for Education Statistics (May 2007), 13.. Laboriously, using a dictionary, many people use their time inside to teach themselves how to read. We must ask ourselves: why is this suspect? Why is self-improvement, when you have been failed by others, being actively prevented?

These ongoing battles against book refusals constitute just a small piece of the hourly violation of incarcerated peoples’ civil rights legitimated by imprisonment. This is why most prison book programs are abolitionist. It’s easy to deny any civil right once you’ve agreed to implement a system that legitimately denies even one civil right under the auspices of ‘punishment.’

Abolition can be a scary word for people, conjuring images of criminals running loose in the streets or, it can seem too idealist—pie in the sky, proffered by people who aren’t in touch with ‘reality.’ People working in prison books programs are neither. Abolition is born from the experience of encountering the system of incarceration again and again as well as knowing many people on the inside through their letters. Through these experiences, prison books programs have realized that what is needed to address the issues we encounter is a completely different way of understanding what’s going on in the most incarcerated nation in the history of the world. As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write, abolition is “Not so much the abolition of prisons but the abolition of a society that could have prisons… and therefore not abolition as the elimination of anything but abolition as the founding of a new society.” Abolition means building something else, something not predicated on the same assumptions as this system that is broken.

I invite you to join us. To find a prison books program near you, visit: https://prisonbookprogram.org/prisonbooknetwork/