The PEN Ten: Jevon Jackson on Uncompromising Truth and What Makes for Good Narrative

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program Director Caits Meissner speaks with Jevon Jackson, who was awarded First Prize in Poetry in PEN America’s 2019 Prison Writing Contest for his piece “All of Us, In Prison.”

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program Director Caits Meissner speaks with Jevon Jackson, who was awarded First Prize in Poetry in PEN America’s 2019 Prison Writing Contest for his piece “All of Us, In Prison.”

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

It was Emily Dickinson’s poem that begins: “Hope is the thing with feathers / That perches in the soul”. I was 18 years old, just arriving into a maximum security prison formidably called “Gladiator School,” with a Life sentence hanging over my head. The way that she wrote about Hope amplified my vulnerability, but it also made me feel empowered “and sings the tune without the words / and never stops at all”. Her language, simple and accessible, but there is a profound elegance to her measure and peculiar rhyme schemes. This poem made me feel something beyond myself, and as I recited it to myself over and over again, the beautiful music of this piece made me understand how someone can turn their pain into art. And at that precarious point in my life I needed that kind of unyielding Hope to get me safely beyond the gladiators and lurking lions of my circumstance.

2. How does your writing navigate the truth?

With good poetry, there must be uncompromising Truth against the palette or the music and the images just won’t work as well. The poet’s balancing act is more about marrying those personal, individual Truths into an accessible, universal Truth that the rest of us can identify with. I feel like I’m always struggling to make my experiences in prison relatable to a reader who would otherwise have no accurate personal reference of what it means to live on this side of the wall. The uncompromising Truth of the conditions where I live can sometimes be cruel, immoral, and deplorable, but there may be a faction of people who read it and refuse to recognize the anguish and dehumanization of it because they believe “that’s how prison is supposed to be.” So I’m constantly searching for ways to connect my personal Truth to a more universal Truth where people, no matter their political or pious perspectives, can feel the same pulse/weight/skin.

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Sometimes the process looks like an overwrought construction worker, with dirt smudges on his sweaty face, dents in his hard hat, and mud caked on the heels of his boots. And sometimes it looks like a giggling little imp of a child jumping about euphorically in a backyard bounce house. I’ve learned to embrace both modes as they come. I wish it was more bounce house than muddy boots, but as every serious Writer knows, most times the writing process itself controls you and the best thing is to be like water and allow it to take you where you cannot see.

Maintaining momentum is really about discipline. It’s about creating a steady, consistent writing routine. Even if it’s just for 30 minutes or an hour every weekday, or a few hours on the weekend, there may be lulls and hesitations along the way but the routine itself is the engine that will push you along and get you where you ultimately need to be.

For inspiration, I believe we need exposure to the unknown and the unfamiliar. It’s the “newness” of the moments where we take a different route home from work or school, listen to an unfamiliar podcast or song, read an author or genre that we’d normally ignore, engage in conversation with someone we’d usually walk right past, eat something weird and different off the menu; it’s in these moments where the expectations of normalcy are suspended and we are open to experiencing the world as it is and not how we color it to be.

4. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about you?

4. What is one book or piece of writing you love that readers might not know about you?

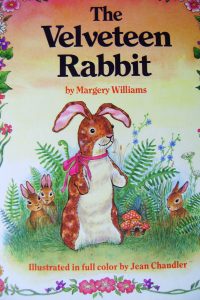

One story that I’ll always enjoy is The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams. Although it’s considered a children’s story, I think it’s one of the more profound stories about the human condition and about the transformation of love. One of my favorite lines is: ” . . . by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby.”

5. How can writers affect resistance movements?

Art can be either a siren, a signal, or a chronicle of what has come before us. When there are enough creative voices echoing the same social or political sentiments, it can send a signal to the rest of the similarly affected masses that we actually have the ability to change our collective circumstance.

6. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

The last book I read was The Making of a Story by Alice LaPlante. This is one of the most phenomenal, most accessible books on the creative writing process that I’ve ever read. For those of us who write and don’t have the MFA experience, this book gives us enough enlightenment to persuade our readers that we are much more captivating writers than we’ve fully realized yet.

What I plan on reading next is a novel that my friend has been raving about: On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong.

7. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

The biggest threat to free expression today is Number 45. For him to be in the highest office, to be the key representative of the United States of America, and then to wage Twitter wars against the press, threaten and demean respected journalists who legitimately examine his public and political sins, and vehemently attack accurate and verifiable news accounts as “fake,” this is the ultimate antithesis of free expression.

Years ago, when I was housed in a different prison, the administrative staff implemented a policy requiring that any creative work we (as prisoners) sent out to be published had to be screened and reviewed by staff. One of the multiple poems I submitted to them for screening was titled “The New Death Row,” and it was a Michelle Alexander-type of criticism of the prison system. Every 30 days or so, I inquired to staff as to the status of the screened material, and either they told me to be patient or it was volleyed to another staff member. After five months of this so-called screening (and a formal grievance filed by me), they informed me that my material was “lost,” and that I would have to re-submit. Clearly, it doesn’t take five months for prison administrative staff to read over a couple pages of poetry. Such behavior by prison officials reveals a collaborative effort, amongst some of them, to purposely disrupt and stifle our ability to freely express ourselves with the outside world, especially when it’s a legitimate criticism against them or the system.

8. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

My identity colors every picture that I create. Being incarcerated for over 25 years, since I was 16 years old, most of what I write touches on this experience. But I eschew the “incarcerated writer” label because my identity is not limited to that of a prisoner. I believe that the concept of identity, itself, is fluid. As human beings, we are an ever-changing thing. From our perspectives to our beliefs to our individual stations in life, all of it is sopped in the flux. What we identified with last year may be a little different to what we identify with tomorrow.

If you mean the “voice” of the writer, then I believe there definitely is such a thing as “the writer’s identity.” And that writer’s identity can be helpful for the reader in gauging their expectations.

“We need stories because we need help in understanding each other and the world that harbors us.”

9. What advice do you have for young writers?

In this order, I would say to, first, learn to write for yourself. Write because it is either a want, a need, or a neurotic spontaneous compulsion. Write within the same enjoyable mode as one would if watching a good enjoyable movie, alone, and noshing on cheesy or chocolatey snacks.

Second, hone your craft by reading constantly and learning to tighten up the technical and structural aspects. This includes being open to constructive criticism.

Third, find your audience. A rejected submission is not an indictment against your capabilities as a Writer. And understand that multiple rejections are all part of a Writer’s work hazard. You must wear a hard-hat when walking about the submission wilderness; what you’re really doing is searching for your audience. And when you do finally find your audience, you must treat them well and learn what you can about them.

10. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

I’d like to meet Emily Dickinson, but not in any conventional way. Because she was a very serene and solitary creature, which is something I can relate to, I wouldn’t want to intrude upon her space with a face-to-face meeting. I would rather meet her through the quiet intimacy of handwritten correspondence and, hopefully, collaborate with her on a few writing projects. To be involved in the quirky ocean of her creative process would truly be a prized adventure.

11. Why do you think people need stories?

It is one of the most elemental parts of who we are as human beings. Whether it was the tribal exchange of the griot and his people, or the biblical principles of sowing parables across the land, we have always learned about and understood the world around us through stories. I think the power of the Narrative taps into our primal and instinctive conditioning to other people. Maybe it’s the mirror neurons in our brains, or something much too scientific for me to comprehend, but good Narratives create a world that we can identify with, populated with people we can relate to, and regardless of the plot or the characters’ journey, the goal is to ultimately get us to feel something worthy of reflection toward the hero (or even the anti-hero).

We need stories because we need help in understanding each other and the world that harbors us.

12. What is one thing you’d like to share with the world about your writing?

The one thing I’d like to share is that when I write about my experiences in prison I’m always mindful of the fact that I committed a crime to be here. I may object to the length of my sentence (life) for an offense that occurred when I was 16, but I’ve always acknowledged that I definitely deserved to go to prison for what I did. My criticism, in my writing, of prison conditions and the criminal justice system as a whole, it has no bearing on the magnitude of my remorse for the pain I’ve caused others in the past.

I think it’s easy for some readers to conflate the two, or assume that I’m not sorry for what I did to be here just because I outwardly challenge some of the inhumane and deficient conditions that I live in. A Writer in prison can be authentically remorseful for his public sins and still respectfully rally against the incarcerated chaos that he has been sentenced to.

Author Bio: Currently 41, I’ve been incarcerated since I was 16 years old. Listening to artists like Kendrick Lamar and Brandi Carlile really helps with my creative writing process. In my free time I enjoy playing Scrabble, chess and a high-stakes remixed version of Monopoly.